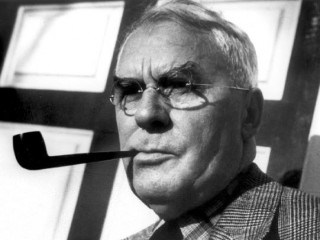

Albert C. Barnes biography

Date of birth : 1872-01-02

Date of death : 1951-07-24

Birthplace : Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Science and Technology

Last modified : 2011-09-27

Credited as : chemist, art collector, Argynol

0 votes so far

Best known for his almost literally priceless art collection, Albert C. Barnes was a physician and pharmacologist who worked at the turn of the 20th century for H.K. Mulford and Company, a medicinal concern in Philadelphia that was later merged into Merck. At the Mulford Company, Barnes and chemist Hermann Hille (1872-1962) developed a new silver/protein compound that acted as an an antiseptic, and the two men then promptly quit to establish their own firm, Barnes & Hille. Their antiseptic was marketed under the trade name Argyrol, widely used to prevent eye infections in infants, and the company was very successful. Barnes, however, soon became irritated at what he perceived as Hille's lackluster contribution to their partnership, and in 1908 he bought out Hille's interest in the business and changed its name to A.C. Barnes Company. After their dissolution the company became much more profitable, and by the early 1910s Barnes was a millionaire. He became a millionaire several times over when he sold the business in 1929, just months before the stock market crash.

Barnes was always interested in art, and he began seriously collecting in 1912, focusing his attention and wealth only on the works that interested him artistically. The artists who caught his eye included several now-famous but then relatively unknown impressionist artists, including Paul Cézanne, Henri Matisse, Amedeo Modigliani, Pablo Picasso, and Auguste Renoir, among others. Barnes was also one of the first Americans to seriously collect African, Asian, and Native American art.

In 1923, he agreed to a brief display of some of his recent acquisitions, including numerous Matisses and Picassos, alongside works by Giorgio de Chirico, André Derain, and Chaim Soutine, at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia. It was the first time that French Impressionist art had been displayed in the City of Brotherly Love, but the response was brutal - critics called the artwork "diseased," "debased," "degenerate," and "most unpleasant to contemplate." Infuriated, Barnes decided that the Philadelphia "art elite" was comprised of phonies and snobs, and he vowed that his collection would never again be publicly displayed in that city.

He opened a small art school in the town of Merion, about five miles outside of Philadelphia, and there his increasingly substantial collection was displayed - but only for students and a very few visitors, who needed to obtain Barnes' permission in advance before visiting. The Foundation was surrounded by a ten foot tall bulwark, described by neighbors as the "spite wall," and the school's proprietor was picky about who would be allowed inside the doors - ordinary people who expressed a sincere interest were usually welcomed, as were celebrities and artists, if Barnes judged their intent to be pure. Others, including the auto magnate Walter P. Chrysler, architect Le Corbusier, and the poet T. S. Eliot, had their requests to visit flatly rebuffed. As a rule, any would-be visitor was turned away is he or she cited a connection with any aspect of what Barnes called "the art establishment."

Barnes could be kind and frequently was, but he was also described as cantankerous, capricious, and unwilling to compromise. He counted John Dewey among his closest friends, and maintained a long correspondence with art critic Leo Stein (1872-1947), the older brother of Gertrude Stein. In 1940, after Bertrand Russell was barred from teaching at City College of New York, Barnes hired Russell to lecture at the Foundation, but these two strong-willed men soon clashed, and in 1943 Russell was fired.

On 24 July 1951, Barnes ran a red light while driving, and he was killed instantly when his Cadillac was rammed by a truck. By then, his collection was said to be the world's finest assortment of post-Impressionist and early modern works, and Barnes was widely respected but perhaps just as widely reviled in the art world, for his astounding collection and his stubborn scrutiny over who could and could not view his myriad masterpieces. And his idiosyncratic control continued, even after his death - his last will & testament gave control of the collection to Lincoln University, a small traditionally Black college, and included excruciatingly explicit instructions that specified how the collection must be maintained and displayed, with a stipulation that the artwork could never be relocated, sold, or loaned out to museums.

Per Barnes' directives, the Foundation was never quite a museum, but instead was operated as an art institute. Only a strictly limited number of visitors were allowed inside, all of whom needed to file detailed applications in order to receive their required visitors' reservations. For several decades after his death, Barnes' collection of art remained at the Foundation, where some visitors were charmed by the small building's seclusion, general coolness, and quirky layout, with paintings hung just inches from other paintings. Other visitors complained that the lighting and parking were inadequate and the rigors for gaining access too daunting.

As the reputation and value of works by Renoir and Barnes' other favorites skyrocketed, this little-seen collection came to be worth more than a billion dollars, though an accurate assessment is difficult to gauge, as the collection's most famous art is so highly regarded that works of such caliber are rarely offered at auction. The Barnes Foundation, however, was poorly managed, and it teetered near bankruptcy through the 1990s and early 2000s. A 2004 court case allowed the breaking of Barnes' will, and in 2011 the Foundation's facility in Merion was closed as construction continues on the new "Barnes on the Parkway" complex in downtown Philadelphia. Largely funded by the city's "art elite" that Barnes despised, the new $150M gallery is scheduled to open in 2012. Reservations will not be required.