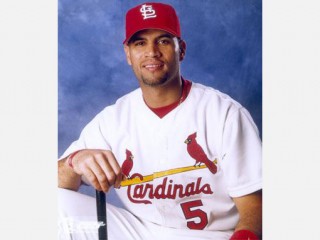

Albert Pujos biography

Date of birth : 1980-01-16

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic

Nationality : Dominican

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2010-11-10

Credited as : Baseball player MLB, first baseman for the St. Louis Cardinals,

0 votes so far

Despite his meager surroundings, Albert grew up happy and well-adjusted. His grandmother deserved much of the credit for his sunny outlook on life. She treated him like her own son and passed along her deep religious beliefs. To this day, Albert adheres to the same strict code of ethics, and is involved in a wide range of charitable causes.

Though Albert didn’t see his father all the time, he knew he wanted to follow in Bienvenido’s footsteps. The elder Pujols, a great pitcher in his day, was known throughout the Dominican Republic. From the time he could walk, Albert showed his father’s passion for baseball. By his sixth birthday, the youngster was playing everyday on the dusty fields near his home. Though he didn’t have any one favorite pro team or player, Albert dreamed of a career in the majors. His favorite player was Julio Franco.

In the early 1990s, members of the Pujols family began migrating to the U.S. Their first stop was New York City, where they hoped a better life awaited. When Albert turned 16, he and his father packed their bags and headed north to join the family. But the Big Apple was more expensive and violent than expected. One day, while running an errand, Albert saw a man shot to death. His grandmother demanded the Pujolses find a safer place to live.

The family settled on Independence, Missouri. On the surface, America’s heartland appeared to be a strange choice for a Spanish-speaking family. But Independence—best known as the birthplace of Harry Truman—was home to an enclave of Dominican immigrants, and its Midwestern values suited the Pujolses perfectly. They took up residence in a small house that seemed like a mansion compared to their Santo Domingo digs. Albert attended his first big-league game not long after, watching the Kansas City Royals host the then California Angels.

Though he knew very little English, Albert made the transition to U.S. culture easily. Baseball was key to this adjustment. In the summers, he starred at shortstop in American Legion ball. Thanks to his soft hands and strong arm, Albert was a natural at the position. At 6-3 with power to spare, he was also a terror at the plate.

Albert Pujos entered Fort Osage High School as a sophomore, a year behind others his age because he only spoke Spanish. He and his cousins were the only Dominicans in the school. Assigned a tutor named Portia Stanke, Albert picked up English quickly. He became attuned to the rhythm of American teenagers, hanging out on weekends with his buddies in basement dens and shopping malls.

A naturally gifted student, Albert had extra motivation, figuring that the sooner he conquered the language barrier, the sooner he would make it to the big leagues.

Baseball dominated just about every part of Albert’s life. He worked out and practiced whenever and wherever he could, establishing a personal dedication to the game that still sets him apart from his peers. Albert had never worked at being a better player before going to Fort Osage. When he saw how quickly the results came, he was hooked.

Stanke remembers Albert being fiercely proud—though not cocky—of his spot on the Fort Osage varsity. On game days he wore his uniform to school. Modesty, however, kept him from bragging about his performance on the field.

In his first season, Albert hit better than .500 with 11 home runs. Fort Osage coach David Fry couldn’t believe his good fortune. The teenager was the hardest worker—and swinger—on the team. Fry remembers one mammoth shot Albert launched at Liberty High School that landed on top of a 25-foot high air conditioning unit some 450 feet from home plate.

The following year, opponents avoided Albert like the plague, offering little in the way of hittable pitches. Still, despite 55 walks in 88 at-bats, he managed to belt eight homers, lead Fort Osage to the state championship and earn All-State honors for the second year in a row.

By his junior year in high school, Albert was attracting the attention of pro scouts. Intrigued by his work ethic, baseball acumen and undeniable talent, they advised him to leave Fort Osage and find a college that would give him better exposure. The idea wasn’t out of the question, particularly because an aggressive course load would allow Albert to graduate in January of his senior year and move right onto the college diamond. Convinced that this plan was his surest path to the majors, he spent the fall with his nose buried in his books.

One of the few breaks he took was to appear in an All-Star Game for high schoolers in the Kansas City area. Among those in attendance was Marty Kilgore, the coach at nearby Maple Woods Community College. Kilgore was blown away by Albert’s strength and knowledge of the game. He recruited the 18-year-old for the spring of 1999.

Meanwhile, Albert was ready to meet another challenge, this one off the field. At a Latin dance club in Kansas City, he met a pretty 21-year-old named Deidre. Completely smitten, Albert lied about his age to get a date with her. When he eventually owned up to his fib, Deidre revealed a secret of her own. She had a daughter named Isabella who had been diagnosed with Down Syndrome. Albert bonded immediately with the infant, and Deidre marveled at the maturity of her teenage boyfriend.

ON THE RISE

When Albert arrived at Maple Woods, his top priority was raising his stock in the upcoming 2000 draft. Landon Brandes, one of the club's top hitters at the time, will never forget the freshman’s first batting practice session. With everyone else on the team swinging aluminum bats, Albert stepped to the plate with a wood model, then blasted several moon shots that outdistanced every other ball hit that day.

In his 1999 regular season debut for Maple Woods, Albert was even more impressive. Starting at shortstop, he smashed a grand slam off future All-Star Mark Buehrle and turned an unassisted triple play. He wound up batting .461 for the year, with 22 home runs and 80 RBIs. Come the Junior College World Series, the scouting report on Albert said it was better to put him on than pitch to him. Brandes received pretty much the same treatment, and throughout the postseason the duo’s bats were silenced with a steady diet of chin music and intentional passes.

By then, however, big-league teams had seen enough to know Albert was a prime prospect. Among the clubs interested in him, the St. Louis Cardinals had watched the hard-hitting infielder the closest. With Albert playing in their backyard, they had been able to keep a close eye on him all year long—particularly talent evaluators Dave Karaff and Mike Roberts. Gambling that they could wait out the rest of the teams in the draft, the Cards didn’t select him until the 13th round. As each round passed, Karaff—Albert’s biggest booster—thought he would lose his mind. The news was a major disappointment to Albert, who expected to go much higher. When St. Louis offered a signing bonus of just $10,000, he turned the Cardinals down.

Instead, Albert chose to play in the Jayhawk League, a Kansas circuit for college-age players, and joined the Hays Larks. Because the team was based some fours hours west of Kansas City, he moved in with his new manager and his wife, Frank and Barb Leo. The most difficult part about the summer was being separated from Deidre and Isabella. They talked on the phone regularly.

On the diamond, Albert continued to develop as a player. Like many summer circuits, the Jayhawk League prohibited the use of aluminum bats. But after his season at Maple Woods, Albert was already accustomed to hitting with lumber in his hands. In 55 games, he topped the Larks in homers and batting average. Leo, however, was awed by Albert’s instincts for the sport. He approached each at-bat with a plan, was prepared for every situation he encountered on the basepaths and in the field, and spent more time picking the brains of his coaches than exploring the nightlife with friends.

At the end of the summer, the Cardinals began to appreciate what they had in Albert and upped their offer to $60,000. He accepted, then flew to Arizona for instructional fall ball. There, he batted .323 and began learning a new position, third base. The Cardinals already had a young, powerful third baseman named Fernando Tatis, and the team figured Albert would be major-league ready by the time Tatis was in his late 20s.

Albert returned home that winter, and he and Deidre were married in a New Year’s Day ceremony. (She jokes that she chose the date so Albert wouldn't forget their anniversary.) After the wedding, the couple and their daughter were hardly ever separated. In fact, when Albert was assigned to the Peoria Chiefs of the Class A Midwest League to start the 2000 campaign, Deidre and Isabella followed.

At Peoria, manager Tom Lawless made Albert the team’s everyday third baseman, and he played like he had been there his entire life. He was named the circuit’s top defensive man at the hot corner, with the best infield arm. The Chiefs were thin on overall talent, but the heart of their order was solid, with Albert joined by future big-leaguers Chris Duncan and Ben Johnson. During a season in which the MWL was dominated by pitchers (seven no-hitters were thrown), Albert finished second in the league with a .324 batting average, and added 32 doubles, 17 home runs and 84 RBIs. He also demonstrated tremendous strike-zone discipline, whiffing only 37 times in just under 400 at-bats.

The team finished under .500, but Albert was voted league MVP and shared honors with Cincinnati Reds farmhand Austin Kearns as one of the circuit’s two best prospects.

Albert’s outstanding play put him on the fast track through the St. Louis farm system. In August, he earned a promotion to the Potomac Cannons, then an affiliate of the Cardinals in the Carolina League. After a strong month by Albert at the Double-A level, the St. Louis brass wanted to see him against Triple-A talent. He was promoted again to the Memphis Redbirds, who were preparing for the Pacific Coast League playoffs.

In seven games, Albert hit .367 with two homers, then led the charge in the first round of the postseason, as Memphis nipped the Albuquerque Dukes to advance to the PCL championship series. The Redbirds faced the Salt Lake Buzz, a Minnesota Twins farm team led by Doug Mientkiewicz, and defeated them for the PCL crown. Albert was named the league’s postseason MVP.

Rising star or not, Albert had a family to feed when the campaign ended. The family moved in with Deidre’s parents, and he went to work at the Meadowbrook Country Club, planning parties and handling other catering duties. The extra money came in handy in January when Deidre gave birth to Albert Jr., who was nicknamed AJ.

MAKING HIS MARK

Albert entered the 2001 campaign ticketed for a full year in Memphis. But that didn’t stop the Cards from planning for his arrival in St. Louis. Over the winter they dealt Tatis to the Montreal Expos for starter Dustin Hermanson and reliever Steve Kline. Young Placido Polanco, a slick-fielding utilityman with a good bat, was slated to split time with veteran Craig Paquette at third until Albert was ready to take over.

In spring training, Albert roomed with Brandes, his buddy from Maple Woods who had also been drafted by St. Louis in 2000. Each night he talked about sticking with the big club, and as the exhibition season progressed, the slugger looked more and more like he might make good on his promise. Hard as they tried, the Cardinals could not find a flaw in his swing. Nor could enemy pitchers.

Not only was Albert among the team’s most productive hitters, his enthusiasm rubbed off on everyone in camp. When the Cards asked him to learn to play first base and the outfield, he happily took extra fielding practice with assistant coach Jose Oquendo. Whenever possible, he also cozied up to St. Louis hurlers, most notably Darryl Kile, to talk about big-league pitching patterns.

For manager Tony La Russa, the question was whether he could make room on the 25-man roster for Albert. The everyday lineup seemed set with Mark McGwire, Fernando Viña, Edgar Renteria and Paquette around the infield, and Ray Lankford, Jim Edmonds and J.D. Drew in the outfield. La Russa also had several dependable bench players, including John Mabry and Bobby Bonilla. Behind the plate, light-hitting Mike Matheny was an excellent receiver who got the most out of a staff headlined by Kile and Matt Morris.

Near the end of the spring, La Russa’s dilemma was simplified when Bonilla hurt a hamstring. The injury enabled the Cardinals to keep Albert, whom they expected to use as a pinch-hitter and occasional starter in the infield and outfield.

To his surprise, Albert found himself in the lineup on Opening Day against the Rockies in Colorado. Playing left field in his big-league debut, he collected one hit in three at-bats. The Cards next traveled to Arizona, where Albert hammered the Diamondbacks with a homer, three doubles and eight RBIs in three games. Included in his offensive barrage was a ringing two-run double off Randy Johnson.

When the Cardinals returned home, La Russa saw no reason to sit Albert. When the 21-year-old went deep in the home opener, he became the first St. Louis rookie to do so since Wally Moon in 1954. By the end of the month, Albert had eight homers, tying the major-league record for newcomers shared by Kent Hrbek and Carlos Delgado. But what amazed his teammates more than anything was his composure. With McGwire now ailing with a bad knee, Albert was hitting in the heart of the order—and not showing the least bit of nerves.

Albert remained on fire through May, and was named NL Rookie of the Month for the second time in a row. When he didn’t slow down in June, the media began a campaign to ensure his appearance in the All-Star game. (His name wasn't on the ballot.) Though he staggered through a two-week slump heading into the break, he was an easy choice when Atlanta manager Bobby Cox filled out his roster. Not since lefty Luis Arroyo in 1955 had a Cardinal rookie made the All-Star team, and when Albert entered the contest in the eight inning (at second base for Jeff Kent), he became the first St. Louis first-year player to play in the Mid-Summer Classic since third baseman Eddie Kazak in 1949.

Albert’s fairy-tale season continued in the second half. With La Russa plugging him into any of four positions—left field, right field, third base and first base—the youngster was carrying the Cardinals in a tight race against the Houston Astros in the Central. Opposing pitchers were adjusting to Albert, of course, but he was remaining a step ahead, yanking balls down the line when they tried to set him up for inside pitches, and lacing hits to center and right when they tried to set him up away.

In August, Albert hit in 17 straight games, including a 453-foot homer at Busch Stadium against the Florida Marlins. Midway through September, Albert spearheaded a nine-game winning streak, and was voted NL co-Player of Week. When it was all said and done, St. Louis and Houston finished knotted atop the division at 93-69. Because of the tiebreaker format, the Cardinals drew a Wild Card berth in the playoffs.

Morris and Kile were the club’s top winners with 22 and 16 victories, respectively. Edmonds and Drew both had big years, too. But Albert was the real story in St. Louis. In 161 games, he led the Cards with a .329 batting average, 194 hits, 37 homers, 47 doubles, 130 RBIs and 112 runs scored.

Named NL Rookie of the Year, he was just the ninth unanimous selection for the award in league history. Albert established franchise rookie records in every significant offensive category, and was the first player to win the club’s Triple Crown since Ted Simmons in 1973.

Unfortunately for Redbird fans, the campaign ended on a sour note in the Division Series, as the Arizona Diamondbacks eliminated the Cards in five tense games. The difference was Curt Schilling, who twice outdueled Morris in classic pitching battles. Albert had trouble in his first taste of postseason competition, going just two for 18 in the series.

During the offseason, Albert embarked on his normal workout routine, waking early every morning for batting practice and weight training. The Cards also geared up for what they hoped would be another exciting campaign. The club signed first baseman Tino Martinez, brought in Jason Isringhausen as the new closer and welcomed starter Woody Williams, acquired late in the ‘01 season, for a full year. Outside of those three additions, St. Louis looked pretty much the same, except for the absence of McGwire, who officially announced his retirement.

When the regular season began, Albert appeared mortal, as NL hurlers drove him off the plate and he struggled to hold his ground. When his batting average in the first half didn’t rise much higher than .280, some questioned where he was a one-year wonder. But Albert stayed confident. He was hitting well with runners in scoring position, his power numbers were strong, and his defensive play improved in the infield and outfield.

Meanwhile, the Cards surged despite some decidedly low moments. First their beloved announcer, Jack Buck, passed away. Then came the most shocking news of the summer: Kile died in a Chicago hotel in his sleep. The well-liked pitcher’s death hit the team and its fans extremely hard. But St. Louis regrouped, and eventually ran away with the Central Division race, posting a record of 97-65. Morris has another sensational year, Williams was great when healthy, Jason Simontacchi surprised with 11 wins, and Isringhausen steadied the bullpen.

Among the position players, Edmonds developed into one of the club’s emotional leaders and remained an offensive catalyst. The Cards also bolstered their lineup with a trade for Scott Rolen from Philadelphia, which officially ended any thought of Albert moving to the position. As much as anything, it was Albert’s scintillating second half that keyed the team’s ascent in the standings. After the All-Star break, he batted .335 with a league-leading 61 RBIs, ending the season as one of four NL players to finish in the top 10 in the Triple Crown categories. (The others were Barry Bonds, Vladimir Guerrero and Jeff Kent.) Bonds walked away with another MVP, while Albert placed second in the voting.

In the postseason, St. Louis again locked horns with Arizona, and this time the Cards got their revenge. In a three-game sweep, the club benefitted from tremendous pitching and timely hitting. With a .300 average for the series, Albert had a major impact on how the Diamondbacks worked against the entire St. Louis lineup.

The Cards next squared off against the San Francisco Giants in the National League Championship Series. In a matchup billed as a showdown between the league’s two most dangerous hitters—Albert vs. Bonds—St. Louis lost in five. The key was the San Francisco bullpen, which recorded two wins and three saves. Albert started hot, homering off Kirk Rueter in Game 1. But after that shot, he saw fewer and fewer good pitches, and no one else in the lineup picked up the slack.

With the start of the 2003 season, Albert was acknowledged as a bona fide superstar, not to mention the heart of a powerful batting order in St. Louis. Edmonds, Rolen, Martinez and Edgar Renteria offered him plenty of support in the lineup, giving the Cards all the offense they needed. The biggest obstacle for the team was its pitching. Morris and Williams formed a solid one-two punch, but both had a history of arm problems. After them, La Russa had a mish-mosh of journeymen and youngsters to sort through. Meanwhile, Isringhausen was coming back from an injury, creating uncertainty in the bullpen.

The club’s pitching ultimately spelled its demise. In the lukewarm NL Central, the Cards hung with the Cubs and Astros thanks to their high-scoring offense. But when Morris missed a chunk of the season with an elbow injury, Williams couldn’t hold the staff together by himself. Down the stretch, the club had no margin for error, and faded from serious contention for the postseason after dropping a September series to Chicago.

Despite a painful elbow injury—which was originally deemed to be season-ending—Albert pulled his weight all year long, though he was forbidden from making long throws when playing in the field. Through the campaign’s first three months, he put himself in position for a run at the Triple Crown. In fact, his .429 batting average in June led some to speculate that he might hit .400 for the year. Two weeks later, Albert treated the fans in the Windy City to an awe-inspiring performance in the ‘03 Home Run Derby during All-Star festivities (though he lost in the final to Garrett Anderson).

As the season progressed, Albert saw fewer and fewer pitches to hit. Even with Rolen and Renteria protecting him, opposing pitchers preferred to take their chances with them. Still, Albert ended with MVP-caliber numbers, batting .359 with 51 doubles, 43 homers and 124 RBIs. In addition, he struck out just 65 times in close to 700 plate appearances.

Heading into the 2004 season, the baseball critics projected the Cardinals as no better than third in the NL Central behind the pitching-rich Cubs and Astros. Once again, a lack of quality arms was seen as St. Louis’ major shortcoming. Newcomers Chris Carpenter, Jason Marquis and Jeff Suppan joined Morris and Williams in the starting staff, but no one expected the rotation to deliver a full season of quality innings. The offense, meanwhile, was still a powerhouse, with Albert, Edmonds, Rolen and Renteria all back in the fold. The Cards also made a couple of key pick-ups for the everyday lineup, including Tony Womack and Reggie Sanders.

Early on, St. Louis was only treading water. That was until a May contest against the Cubs at Wrigley Field. Albert and Edmonds hit back-to-back home runs in the fifth inning, the Cardinals gutted out a 7-6 victory, and they never looked back. St. Louis went on to a 105-57 record, the best mark in baseball, and took the division by 13 games. Carpenter, Marquis and Suppan all pitched above expectations, and Isringhausen finished among the league leaders in saves.

Of course, St. Louis relied heavily on its big bats. Rolen enjoyed the finest year of his career, Edmonds cracked 42 homers, and the club added three-time batting champ Larry Walker late in the campaign. Albert was also terrific. Though slowed a bit in the first half by a sore hamstring, he was an easy choice for the All-Star team. His numbers by the break—a .304 batting average, 22 home runs, 60 RBIs and an on-base percentage of .400—were right there with the NL's best.

As his leg healed, Albert increased his production. With superb protection in the lineup, he showed more patience at the plate and became an even better hitter. He ended the campaign hitting .331, and set career highs with 46 home runs and 84 walks. Albert also slashed 51 doubles, and struck out just 52 times. His 389 total bases were tops in the league, and no one in the majors scored more runs (133).

St. Louis fans had high hopes going into the playoffs. The Cards hadn’t won the World Series since 1982, and they believed the club would end the jinx. Standing in the way in the NLDS was Los Angeles. The Cardinals had a surprise in store for the Dodgers. For the first time in a month, all eight position players were healthy. In Game 1, the offense blasted a Division Series-record five home runs, as St. Louis cruised, 8-3. The next day, light-hitting catcher Mike Matheny drove in four runs, and the Cards won again 8-3.

The Dodgers responded on their home turf in Game 3, but that was their last gasp. Behind Albert one night later, the Cardinals ended the series with a 6-2 victory. His three-run home run in the fourth inning gave the team a lead that it never surrendered.

In the NLCS, St. Louis squared off against the surging Astros and their switch-hitting star, Carlos Beltran, who joined the team at mid-season in an interleague trade with the Royals. The Cards came out swinging in Game 1, pounding out 12 hits in a 10-7 victory. Albert spearheaded the charge, reaching base four times, including a home run. He produced again in Game 2. With the score tied 4-4 in the eighth, Albert ripped a homer off Dan Miceli. Rolen followed with a long ball of his own, and St. Louis went up 2-0 in the series.

When the action switched to Houston, the Astros dominated, taking all three games in their home park, as Beltran proved unstoppable at the plate. Albert had a home run and three RBIs at Minute Maid, but it wasn't enough.

Facing elimination in St. Louis in Game 6, the Cardinals responded with a clutch effort. Morris was serviceable through five innings, and then La Russa turned to his bullpen, which yielded only one run over the next seven. Albert, meanwhile, continued to carry the offense. He homered in the first inning, and doubled and scored in the third. In the 12th, Miceli chose to pitch around him, which set the stage for Edmonds, who launched a dramatic walk-off home run.

Game 7 was tight for five innings, as Suppan battled Roger Clemens. In the sixth, the Cardinals finally got to the veteran righty. Albert had another big hit, a double that chased home Roger Cedeno with the tying run. Rolen next lined a two-run homer to left, which was all the cushion St. Louis needed. The Cards held on for a 5-2 victory, and celebrated their first trip to the World Series since 1987.

Albert’s postseason stats were spectacular. He finished the NLCS with a .500 batting average, 1.000 slugging percentage, five home runs and 11 RBIs. He was the obvious choice as series MVP.

In the World Series against the Boston Red Sox, the high-flying Cardinals came crashing down. St. Louis had a chance in Game 1, but Rolen and Edmonds missed several chances to break open the contest at Fenway Park. From there, the Cards looked flat and barely mustered a challenge. The Sox swept them easily, winning Games 3 and 4 in St. Louis. The Cardinal offense received a lot of criticism, particularly Rolen and Edmonds, who collected one hit between them against the Red Sox. By comparison, Albert did considerably more damage, hitting .333. But he finished without a home run or RBI, even though Boston pitchers often went right after him.

The Cardinals were odds-on favorites to repeat as NL pennant winners in 2005, and even with a shoulder injury to Rolen, they still dominated the Central, finishing ahead of the Astros by 11 games. The team had a new DP combo, with hard-nosed David Eckstein and Mark Grudzielanek taking over for Renteria and Womack. They also added a top-of-the-rotation starter in free agent Mark Mulder, who teamed with 21-game winner Carpenter to give St. Louis an awesome one-two punch.

Albert scorched the ball all year, leading the league again with 129 runs scored and belting 41 homers with 117 RBIs. He also led the team with 16 stolen bases and demonstrated admirable patience without Rolen’s protection, walking a career-high 97 times. In the NL batting race, Albert went down to the wire with Derrek Lee, finishing second, .335 to .330.

The Cardinals disposed of the Padres in a three-game NLDS sweep that saw Albert hit .556 and draw three intentional walks. San Diego chose to pitch to Sanders instead, and he killed them with 10 RBIs.

All that stood between the Cards and a return trip to the World Series were the Wild Card Astros. With Beltran now a Met, St. Louis’s 2004 nemesis was no longer a factor. But the Astros proved the power of pitching in a short series, getting solid starts out of Andy Pettitie, Roy Oswalt and Roger Clemens to win the first three games.

St. Louis won a 2-1 squeaker in Game 4 to stave off elimination, but the Astros seized control of Game 5 with three-run seventh inning to take a 4–2 lead into the ninth. Albert came up with two out and two on against Brad Lidge and crashed one of the longest and most dramatic home runs in postseason history to win the game. Unfortunately for the Cardinals, Oswalt was untouchable in Game 6, and the Astros celebrated their first pennant in the final game played at old Busch Stadium.

Despite having to watch the World Series at home that fall, Albert had a November to remember. He and Deidre had a daughter, Sophia, and Albert was named NL MVP, edging Andruw Jones.

As the 2006 season started—and new Busch Stadium opened—Albert was more focused than ever on winning his first world championship. Along with the Mets, the Cardinals had the NL’s best top-to-bottom lineup, plus a very good pitching staff led by Carpenter, now the league's defending Cy Young Award winner.

April belonged to the Cards and Albert, who launched 14 homers. By the end of May, he was sitting at 25 round-trippers with 65 RBIs, and was the only player mentioned when MVP conversation started. An innocent swing in early June altered the course of his season, however, as he went on the DL for the first time with a strained oblique muscle. Some estimates had Albert on the mend for eight weeks or more, but he returned to the lineup on June 21st and went 4-for-4 in his second game back. Although his power was curtailed slightly, he had a torrid July, batting over .350 as the Cardinals opened a big lead on the Reds and Astros.

The injury bug bit other Cardinals in the summer and fall, but the team maintained an even keel. When Isringhausen was lost for the year in August, rookie Adam Wainwright filled his shoes. The team replaced concussed centerfielder Edmonds by signing Preston Wilson, who did a nice job at leadoff when Eckstein was on the shelf.

Albert had a great final month, enabling St. Louis to barely survive a late surge by the Astros and win the division title with a meager 83 victories. His best home-stretch performance came against Pittsburgh in early September, when he homered three times with thousands of Down Syndrome kids in the stands cheering him on. (They were part of the Buddy Walk charity Albert has chaired since 2002.) It was his second three-homer day of the season.

Despite missing time and playing through nagging injuries for most of the year, Albert still posted career-highs with 49 home runs, 137 RBIs, and a .671 slugging average. Had his team not faded down the stretch, he would have been a lock for MVP.

When the playoffs began, everyone was healthy and back in the lineup. Still, no team in history had won a championship after so few wins. Once again, the Cardinals defeated the Padres in the NLDS with ease, setting up a showdown with the Mets for the pennant.

New York’s pitching staff was a mess, and the Cardinals were going into battle with an inexperienced rookie as a closer. The Mets pitched around Albert whenever possible in an exciting see-saw series, leaving the heroics to teammates Suppan and catcher Yadier Molina, who delivered the pennant-winning homer in Game 7 at Shea Satdium. Molina was a player whom Albert had taken under his wing, and whose confidence he had buoyed through a couple of rough hitting patches in ’05 and ’06. Albert looked like a proud parent in the locker room after the game.

The unlikely NL champs faced the even-unlikelier AL champion Tigers in the World Series. Jim Leyland instructed his pitchers not to give in to Albert, but the Detroit skipper was helpless to fix their shoddy mound defense, which proved the difference in the series. The Cardinals won the championship in five games. After a 7–2 St. Louis win in the opener, the rest of the series was close, but the Tigers could not get the big hits when they needed them. Albert batted just .200, with a double, homer, and five walks. However, the Cardinals’ big man could not have been more delighted when their littlest man, Eckstein, was named series MVP.

The afterglow of Albert’s first championship was dimmed somewhat when he learned that he had finished a close runner-up to Ryan Howard in the NL MVP race. Still, Albert had never been a collector of trophies or accolades. Heck, he sometimes got angry with reporters when they tried to soften him up with compliments.

The 2007 Cardinals were never really in the running, finishing six games below .500. Although Albert led the team in almost every offensive category, he was part of the problem. Albert got off to a slow start in the first half, and was a member of the team’s walking wounded in the second half. It was a credit to his talent and desire that he enjoyed a torrid 10 weeks after the All-Star break, playing virtually the entire time with hamstrings so sore that La Russa ordered him not to run out grounders. Even so, Albert ended up hitting .327 with 32 homers and 103 RBIs. He became the first player ever to start his career with seven 30-homer seasons. A year later he would run that record to eight.

The Cardinals were spectators in the Central again in 2008, finishing behind the Cubs and Brewers, both of whom made the playoffs. Healthy again, Albert had a spectacular season. The fun began on Opening Day when he reached base for the first of 42 consecutive games—the longest streak in almost a decade.

A strained calf and sore elbow curtailed his performance somewhat, but his numbers were still spectacular. Albert finished just behind Chipper Jones in the batting race with a .357 average. He added 44 doubles, 37 homers, 100 runs and 116 RBIs. Albert led the league in total bases for the third time (with 342) and in slugging for the second time with a .635 mark. Albert also reached the 100-walk plateau for the first time.

When the MVP votes were tallied, this time it was Howard of the world-champion Phils who finished a close second in the balloting. Albert had his second award. Of course, he would have traded it in a heartbeat for another World Series ring. Albert’s MVP reignited debate over the meaning of “most valuable” versus “best” player. There really was no debate. The Cardinals all but admitted they were punting the ’08 season—their surprising 86 wins were a tribute to Albert’s value.

The 2009 season was a landmark one for Albert, and it began with a bang as he amassed nine hits and nine RBIs in the first week. He continued to scorch the ball as the Cards dealt with one setback after another. The left side of the infield was a shambles, two oif the team’s starters were unavailable for long stretches, and no one knew who the closer was until journeyman Ryan Franklin nailed down the job. By the end of June, however, the Cardinals were at or near the top of the NL Central, thanks in large part to Albert’s 30 home runs.

St. Louis, in turn, pursued roster-bolstering moves that secured the services Matt Holliday, Mark DeRosa and John Smoltz. The Cards surged to a first-place finish in the NL Central. But that success did not continue in the playoffs. Although many picked St. Louis to reach the World Series, the Cards fell to the Dodgers in three excruciating losses. Los Angeles simply refused to pitch to Albert during the series. He went 3-for-10 with three walks and didn't see more than a half-dozen pitches that were worth swinging at. Meanwhile, the LA hurlers were able to handle his teammates with relative ease.

Despite the year’s sudden end, in many ways Albert’s season was his best ever. He hit .327 and led the league with 124 runs, a .658 slugging average and .443 on-base percentage. He poked 47 balls out of the park to tie for the league lead with Prince Fielder and drove in 135 runs. Albert also walked a career-high 115 times. After the season, Albert was a unanimous choice for his second straight NL MVP award, outdistancing Hanley Ramirez and Ryan Howard by 200-plus points. In every way, Albert’s year defined what a most valuable player is.

Albert has put up early-career numbers that are unmatched in league history. It seems clear he is on his way to rewriting team records that were once thought to be etched in stone. Yet in the end, the only thing that makes him truly happy in baseball is winning championships. Long before Albert ever sipped locker room champagne, he maintained that—regardless of your numbers—there’s no such thing as a “great” year if you are watching the World Series on TV.

To this day, Albert's priorities remain simple. Faith. Family. Baseball. Not that fans in St. Louis are complaining. Already he has added his name to the franchise’s short list of all-time greats. His flowing, powerful swing brings back memories of Stan Musial, his eye-popping production compares favorably to Rogers Hornsby’s, and his commitment to excellence is vintage Bob Gibson. Just imagine if Albert put baseball at the top of his list.

ALBERT THE PLAYER

Albert doesn’t consider himself a classic slugger. He says he’s a line-drive hitter who has the ability to lift the ball. For him, home runs are almost a happy accident, not a planned result.

Much of Albert’s success is derived from his ability to hit to all fields. Thanks to near perfect balance, he has amazing plate coverage, and can drive pitches to left, center and right with equal effectiveness. Albert also possesses some of the quickest hands in the game. His power is a combination of his strength below his waist and the speed with which he whips the bat through the strike zone.

Preparation is one of Albert’s assets, too. He devotes countless hours to situational hitting, while maintaining the flawless consistency of his swing. Albert approaches every at-bat with a clear idea of what a pitcher will throw him and how he will react. His discipline at the plate is evidenced by the fact that his strikeout totals continue to drop, while his walks increase.

Albert is among the most respected players in baseball. Teammates and coaches appreciate—and feed off—his commitment to winning. He also earns high marks for working as hard on his defense as his offense, winning his first Gold Glove in 2006. And though he’s slow, he has learned to be a good baserunner.

Thus far in his career, Albert has been a quiet leader who always seems to come through in the clutch. If he needs to become more vocal as he ages, there’s no reason to expect he’ll have problem with that role.