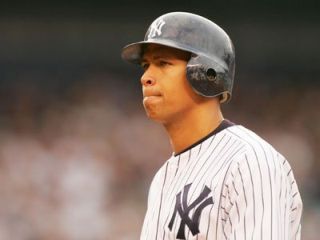

Alex Rodriguez biography

Date of birth : 1975-07-27

Date of death : -

Birthplace : New York City, New York, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2010-07-27

Credited as : Baseball player MBL, A-Rod,

2 votes so far

GROWING UP

Alexander Emmanuel Rodriguez was born on July 27, 1975 in New York City, New York. His parents, Victor and Lourdes, owned a shoe store in Washington Heights and lived in a small apartment behind it. Natives of the Dominican Republic, they planned to one day return to their homeland with Alex and his siblings, Susy and Joe. The couple worked hard to make it happen. Victor manned the store and watched the kids, while Lourdes left before dawn each morning for her job at a car factory north of the city.

Victor was a big baseball fan. A good player as a child, he passed his love of the game on to Alex. Victor gave his son a plastic bat and rubber ball, and the youngster was immediately hooked. He practiced his swing every chance he got, including in the Rodriguez store. Victor often had to send Alex on his way with Joe or Susy to play pinball at pizza parlor up the block.

By the time Alex was four, his parents had saved enough to buy a four-bedroom house in Santo Domingo, just a block from the Caribbean. Victor and Lourdes opened a pharmacy, and the family lived comfortably in their new home. The only problem for young Alex was the bus ride to school, which made him nauseous nearly every morning.

Initially, the Rodriguezes were very happy in the Dominican Republic. But the country’s shaky economy took its toll, and the family business failed. Victor and Lourdes moved the clan back to the U.S., this time settling in Miami. To this point, Alex spoke Spanish only. When he enrolled in Everglades Elementary School, he had to learn English. During the two years he needed to become bi-lingual, Alex found it difficult to keep up with his classmates.

The saving grace for Alex during that period was baseball. He played constantly with his friends. Together they made up a game with old license plates that they called Platicka.

After his ninth birthday, Alex met Juan Diego Arteaga, who coached a youth-league baseball team that practiced at Everglades Elementary. In search of an extra player one day, Arteaga asked Alex if he knew how to play catcher. Alex lied, and said he did. Afterwards, Arteaga introduced Alex to his son, J.D. The two became fast friends.

The chance meeting was a turning point in Alex’s life. Victor soon went north looking for work in New York, never to return. Forced to raise three kids on a small salary, Lourdes—who worked two different waitressing jobs—accepted help from friends in the neighborhood. Alex often turned to Arteaga for moral support.

Baseball became everything to Alex. With no big-league clubs in Florida, he adopted the New York Mets as his favorite team. Alex also followed the Atlanta Braves. His first baseball hero was Dale Murphy. In fact, 10-year-old Alex took jersey #3 in honor of the two-time NL MVP. He was also a big fan of Keith Hernandez.

Alex liked basketball, football and soccer, but baseball was his top sport. Along with J.D., he joined the Boys and Girls Club of Miami, where he starred at shortstop. His coach, Eddy Rodriguez, had helped develop other young phenoms in the area, including Rafael Palmeiro, Danny Tartabull and Jose Canseco. He looked after Alex and made sure the youngster had a glove and spikes.

In his first season for the Boys & Girls Club, Alex led the league in hitting. Over the ensuing years, the team established itself as one of the country’s best. Alex twice led the club to national titles and three times to the city championship.

In seventh grade, Alex started a two-year stint at Kendall Academy. He next moved onto Miami’s Christopher Columbus Catholic High School. But when he didn’t win the starting shortstop job on the varsity, his buddy J.D. convinced him to consider Westminster Christian, a private school with an enrollment of 300. Under coach Rich Hofman, Westminster had built one of Florida’s top baseball programs. Hofman already had a pair of top prospect in first baseman Doug Mientkiewicz and shortstop Alex Gonzalez. Alex would give the Chiefs another big bat in the infield.

Hofman arranged for financial aid for Alex, and in the fall of 1990, the teenager began making the daily 30-minute commute to school. Alex fit in well at Westminster. A star in football, basketball and baseball, he also excelled in the classroom.

Among his new friends was Gonzalez. The two shared duties in the middle infield in the spring of 1991, but Alex was the weaker hitter. For the year, he batted just .256.

Alex's transition on the gridiron went much smoother. A natural at quarterback, Alex had to his strong arm and always demonstrated poise under pressure. During the 1991 campaign—his first as Westminster’s starting signal-caller—he led the team to a 9-1 record. Wearing #13 as a nod to his football idol, Dan Marino, Alex set several state passing records.

The year took on even greater meaning for Alex because of a tragedy he had experienced the previous. During halftime of a football game, Arteaga collapsed and died. Alex sorely missed his surrogate father.

ON THE RISE

Alex bulked up over the offseason, and his confidence spared as he entered his second baseball season at Westminster. He also got a thrill when he was greeted by Cal Ripken Jr. while attending a Baltimore Orioles spring training game. Coming off his second AL MVP, the All-Star shortstop was the player Alex emulated whenever he took the field.

Ripken would have been proud of Alex’s junior campaign. In 35 games, he hit .477, scored 51 runs and stole 42 bases. Westminster went 33-2 and was voted the nation’s top squad in two coaches’ polls. Alex then joined the U.S. national team for the World Junior Championships in Mexico. During the tour, he batted .425 and led the Americans to a second-place finish.

Alex returned home to a mess in Miami. Hurricane Andrew had ripped through south Florida. The Westminster campus had been devastated. There was talk of canceling the football season, but the school felt that fans needed a diversion. Alex earned All-State honors for the second year in a row, but the team had an up-and-down year.

Alex decided to skip basketball that winter. Still recovering from a wrist injury during the football campaign, he was determined to be at full health for his final year of baseball. Alex had committed verbally to the University of Miami, but he also had his eye on the pros. And the pros had their eye on him. Acknowledged as a blue-chip prospect, Alex had scouts following him everywhere. More than 25 watched him during his first scrimmage. Twice that many attended Westminster’s first regular-season game.

Alex enjoyed another huge year in 1993. Batting leadoff, he hit .505 with nine home runs and 35 steals. Just as impressive was how he handled his newfound celebrity. Alex benefited greatly from some advice given by Derek Jeter, the previous season’s high-school phenom. A mutual friend had introduced them to each other, and Jeter offered tips on everything from dealing with the press to picking an agent.

By June, it appeared that Alex would be drafted in the first few picks—perhaps even #1. That selection belonged to the Seattle Mariners. He let the M’s know that he would prefer to go to the Los Angeles Dodgers, who owned the next pick. If Seattle chose him, Alex cautioned, the team would have to be prepared to pay—otherwise he would opt for college. Pulling the strings was agent Scott Boras, who was reviled by big-league GMs for being a tough-as-nails negotiator. Boras worked through Alex’s sister, Susy, to inform the Mariners that it would take $2 million to sign Alex.

Undaunted, Seattle took Alex with the top pick, and then flatly refused to meet Boras’s demands. A long and sometimes ugly negotiation ensued, delaying Alex's first pro summer. He passed the time by competing for a spot on Team USA. Alex was the first high schooler ever asked to try out. He would have made the squad, too—were it not for a deal Boras had cut with Classic Games.

Alex had promised to give Classic the exclusive rights to print his rookie card that year, but Team USA had a standing agreement with Topps for cards of its players. Alex was not allowed to play for the American squad if he planned to honor his contract with Classic, and Classic had no intentions to let him out of the contract. Alex, therefore, had to play for a junior team that summer.

Meanwhile, negotiations with the Mariners were not going well. Boras gave the M’s until the beginning of the fall semester at Miami to sign his client. Otherwise, Alex would enroll in college.

AWith the summer wasting away, Alex got a major scare. While he was sitting in the dugout that July, a foul ball rocketed off a teammate’s bat and grazed the side of Alex's head, narrowly missing his eye. That was it—he took out an insurance policy with Lloyds of London and ordered Boras to finalize a deal with Seattle. When no more progress was made, Alex bypassed his agent and agreed on his own to a $1.3 million bonus.

lex, still 18, reported for his first spring training in February of 1994. The Mariners assigned him to the Appleton Foxes of the Class-A Midwest League. His manager there, Carlos Lezcano, worked on polishing his skills. In 65 games, Alex batted .317, which earned him a promotion to the Jacksonville Suns of the Southern League. By July, the Seattle brass deemed him ready for the majors and called him up for a game in Boston. Ken Griffey Jr. requested that Alex get the locker next to his.

The jump to the big leagues was too much for the teenager. In his first four weeks, he struggled to hit above .200. The Mariners sent him to Calgary of the Pacific Coast League. With the Cannons, Alex regained his stroke, producing a .311 average. He spent the following winter in the Dominican Republic developing the patience and pitch recognition necessary to succeed at the major-league level.

To start the 1995 campaign, Alex was assigned to Seattle’s new Triple-A club, the Tacoma Rainiers. He played well enough to earn a spot on the big club, but every time the Mariners recalled him, they demoted him soon after. When Alex got yo-yo’d for the third time, he phoned his mother. Lourdes dispensed a little tough love, ordering him to suck it up. Shocked out of his depression, Alex earned a fourth promotion to Seattle in August—and never looked back.

Alex joined the Mariners in the middle a heated race with the California Angels. Manager Lou Piniella used him at shortstop to spell veteran Luis Sojo. Alex occasionally got some at-bats as a DH, as well. The youngster provided Seattle with a nice spark, collecting six doubles, two triples, five homers and 19 RBIs. Behind stellar seasons from Griffey, Edgar Martinez and Randy Johnson, the M’s caught the Angels, and then beat them in a one-game playoff.

In the Division Series, Seattle overcame the Yankees in five dramatic games. The Mariners won the series on a clutch double by Martinez, who had 10 RBIs against New York. The team, however, could not muster the same magic against the Indians in the ALCS. After carving out a series lead, Seattle dropped three in a row to Cleveland and lost in six games.

Heading into 1996, Piniella informed Alex that he was Seattle's starting shortstop. Jeter got the same news from Joe Torre that spring, and the two friends celebrated their good fortune. Because Alex had logged over 100 plate appearances the previous year, he was not eligible to for the Rookie of the Year. So he rooted for Jeter, who ended up winning the award with an excellent season.

Jeter’s numbers, however, paled in comparison to Alex’s. His first full year ranked among the greatest in history, earning him Player of the Year honors from both The Sporting News and Associated Press. Alex led the league in batting (.358), doubles (54), total bases (379) and runs scored (141)—all new franchise marks. He added 36 homers and 123 RBIs. Much of that damage was done from the ninth spot in the order, which might have cost Alex the votes he needed to beat Juan Gonzalez for the AL MVP. Alex missed the award by a mere three points.

Alex led an offense that produced 245 home runs and topped the league in runs scored. Yet even with that lusty hitting, Seattle didn’t have the talent to defend its division title. Pitching was the main problem. Johnson was hurt, leaving a staff of no-names to fill in the rotation. The bullpen was also a shambles, with no reliable closer emerging. With a record of 85-76, Alex and his teammates watched the playoffs from home.

In 1997, Mariners GM Woody Woodward acquired starters Jeff Fassero and Scott Sanders to go with Johnson and Jamie Moyer, who had been acquired during the previous season. Piniella, meanwhile, penciled in Norm Charlton, whom he had managed in Cincinnati, as his closer.

Five Mariners hit at least 20 home runs, paced by Griffey’s 56 round-trippers. The sweet-swinging lefty also batted .304 and drove in 147 runs to capture his first MVP award. By contrast, Alex struggled to match his 1996 production. His numbers fell across the board (.300, 23 HRs, 84 RBIs), while his error total climbed to 24, the most by any shortstop in the league. Still, Alex tied for the team lead with 40 doubles and ranked third with 176 hits.

Alex actually broke from the gate quickly. In June, he hit for the cycle against the Detroit Tigers. At 21 years and 10 months, Alex became the fifth-youngest player in history to accomplish this feat. Later that month, he collided with Roger Clemens during a play at the plate and went on the DL with a badly bruised chest. The injury never healed completely, ruining a promising year.

The Mariners got enough pitching to finish first the AL West with a 90-72 mark—the best in franchise history. In the playoffs, they drew the Baltimore Orioles, who had posted the league’s best record. Seattle got trounced. Behind Mike Mussina and Jimmy Key, the O’s shut down the mighty Mariners, taking the series in four games. Alex batted a respectable .313 against Baltimore, but delivered just one extra-base hit.

MAKING HIS MARK

After his injury problems in ‘97, Alex approached the offseason with a new mindset. He hired Michael Jordan’s personal trainer and worked himself into the best shape of his life. At 6-3 and a little more than 200 pounds, Alex felt stronger, quicker and more flexible than ever.

Alex's time in the gym also had a beneficial effect on his personal life. There he met Cynthia Scurits, who worked as a high school psychology teacher in Miami. The two began dating and eventually married, in November of 2002.

The Mariners, meanwhile, were also feeling excited about the future. Their offense boasted plenty of power, while their rotation was set with a trio of lefties in Johnson, Fassero and Moyer. It became clear by the All-Star break, however, that a pennant was not in the offing.

Once again, the problem was the bullpen. Charlton had been replaced as the team’s closer by Heath Slocumb midway through the previous campaign, but the big righty could not hold the job. Eventually, veteran Mike Timlin filled the role, but the M’s had sunk too far in the standings by then and decided to pull the plug on their season. Seattle traded Johnson to the Houston Astros for Freddy Garcia and Carlos Guillen, and then finished nine games under .500.

The campaign’s saving grace was the dynamic duo of Junior and Alex. For the second year in a row, Griffey hammered 56 long balls. Alex clubbed 42 and added 46 stolen bases to join Jose Canseco and Barry Bonds as history’s only 40-40 players. The league leader in at-bats (686) and hits (213), Alex hit .300 for the third straight year and was named the Players Choice AL Player of the Year and Seattle's co-MVP with Griffey.

Alex started hot, tying a record in April with eight extra-base hits over three game. In July, he made the All-Star team for the third time of his career. He capped the year with his second Silver Slugger Award.

The Mariners suffered through another disappointing year in 1999, finishing 16 games behind the Texas Rangers. Garcia emerged as a top-flight starter and Jose Mesa did a good enough job closing, but the club’s middle relievers were atrocious. Wasted was another fine season by Griffey, who finished with 48 homers and 134 RBIs, despite rumors that this would be his final season in Seattle.

Alex, meanwhile, suffered the first major injury of his career when he tore cartilage in the left knee during the season’s first week. He underwent surgery and rehabbed for more than a month before returning. Alex homered in his first at-bat after coming off the DL. By then, however, the Mariners were barely treading water.

Alex found his rhythm and moved into September with his average well over .300. But a month-long slump saw him dip to .285 to finish the season. Still, his numbers were impressive. In 129 games, he put up 42 home runs, 111 RBIs and 110 runs. His long ball total was fifth best in the league, and his slugging average (.586) was sixth best. He also stole the 100th base of his career.

As the 2000 season approached, Seattle officially became Alex’s team. Afraid of losing Griffey to free agency, the Mariners shipped the slugger to Cincinnati in exchange for Mike Cameron, Brett Tomko and a few spare parts. To many fans, it appeared the club was waving the white flag. But the font office had an ulterior motive—creating more balance on the roster. John Olerud returned to Seattle to play first base, jack of all trades Mark McLemore was signed to give Piniella more flexibility with his lineup, and Aaron Sele, Arthur Rhodes and Japanese reliever Kaz Sasaki were brought in to shore up the pitching staff.

Every move Seattle made was predicated on an important assumption: Alex was ready to carry the team. Though he was due to be a free agent at season’s end, he indicated a genuine desire to stay in Seattle. If Alex could handle the strain of being the clubhouse leader, the Mariners had enough talent to win the AL West.

From Opening Day, Alex played with fresh determination. Selected AL Player of the Week in early April, he was stinging the ball to all fields. Before long, enemy hurlers began pitching around him. In one contest, the Kansas City Royals walked him five times. But with ageless Edgar Martinez also swinging a scorching bat, opposing teams soon realized the futility of this strategy.

In July, Alex suffered a concussion after getting kneed in the head while breaking up a double-play against the Dodgers. He also strained his right knee in the collision, which forced him to the DL. When Alex returned, he sparked the Mariners in their neck-and-neck race with the Oakland A’s.

Coming down the stretch, however, Alex fell into a terrible slump. Not only was the division crown in jeopardy, the Indians were threatening to seize the Wild Card.

With only three hits in a span of 29 at-bats, Alex was the subject of tremendous speculation. Fans assumed his ticket out of town was already punched. But Alex heated up with the pressure on and keyed the drive to Seattle’s first playoff appearance in three years.

In the Division Series, the Mariners squared off against the Chicago White Sox. Thanks to strong pitching and timely hitting, Seattle registered a three-game sweep. The Sox choose to deal with Alex carefully, and he had little impact, batting .308 with two RBIs.

Up next were Jeter and the Yankees in the ALCS. With his first real shot at the World Series, Alex raised his level of play. In Game 1, he went deep in a 2-0 win. Though New York’s superior starting staff took control from there, Alex didn’t stop hitting. His average for the series was a lusty .409. Jeter, however, got the last laugh, as the Yanks captured the pennant in six games.

Disappointed by the campaign’s conclusion, Alex had much to reflect on over the winter. He had enjoyed another marvelous year, batting .316 with 42 home runs and 132 RBIs. Ranked in the top 10 in virtually every offensive category, he also displayed newfound patient at the plate, establishing a career-high with 100 walks.

There was no question that Alex was the most treasured prize on the free-agent market that winter. Despite his ties to Seattle, he shopped around, making it clear that the Mets were an extremely attractive option. But when Boras demanded several outrageous perks, New York abruptly ended negotiations. Alex attempted to do some damage control, but it was too late.

Meanwhile, Texas owner Thomas Hicks entered picture. With the Braves also in the running, the Rangers blew everyone out of the water with an offer of $252 million over 10 years. Though the club had finished dead last in the the AL West in 2000, Alex made the same mistake so many stars before him had: He said yes to the money and forgot how bad it felt to lose. Hicks, figuring Alex would send TV ratings soaring, especially on his Spanish-language broadcasts, believed it was money well spent. He was in for a rude wake up call, too.

In Texas, excitement for the 2001 campaign quickly reached a fever pitch. Ticket sales jumped dramatically, and merchandising revenues rose by 25 percent. Between Alex and veterans Ivan Rodriguez, Rafael Palmeiro and Rusty Greer, manager Johnny Oates had a quartet of proven run producers. Youngster Gabe Kapler, Michael Young and Mike Lamb were all promising hitters.

Unfortunately for Ranger fans, the offensive smorgasbord didn't translate into victories. Texas finished last in the division for the second year in a row, posting a record of 73-89. A baseball PhD wasn’t required to identify the club’s weaknesses. The Rangers had the worst pitching in the AL. The rotation of Kenny Rogers, Darren Oliver, Rick Helling and Doug Davis couldn’t stay healthy, which was actually a mixed blessing—not one of the four was particularly effective at full strength. The only pitcher who pulled his weight was Jeff Zimmerman, who notched 28 saves and a 2.40 ERA.

Alex began the year slowly, but by mid-June, his average had climbed into the .330s. He was murder at home, where the friendly confines of the Ballpark at Arlington suited him perfectly. After a brief slump in August, Alex sizzled down the stretch and finished with numbers that in most years would have earned him the MVP. The league leader in home runs (52), runs scored (133) and total bases (393), he batted .318 with 135 RBIs and stole 18 bases in 162 games.

Alex won the Hank Aaron Award as the AL’s top offensive player. His 52 round-trippers surpassed Ernie Banks’s 1958 record for shortstops. Alex also came into his own on defense, topping the AL in putouts and ranking second in assists, chances and double plays.

Alex enjoyed another huge year in 2002. He led the majors in homers, RBIs and total bases to become the first player to pull this triple since Tony Armas in 1984. His two best months were July (.349, 12 HRs, 27 RBIs) and August (.339, 12 HRs, 27 RBIs). Alex also collected his first Gold Glove.

In recognition of his incredible campaign, The Sporting News named Alex its Player of the Year. That made him only the seventh man to claim the award twice. He joined Ted Williams, Barry Bonds, Sandy Koufax, Joe Morgan, Stan Musial, and Cal Ripken on the list.

Alex’s heroics had little impact on the standings, however. Texas wound up in the AL West cellar for the third straight year. Hicks had tried to fix the team’s problems through free agency and trades, acquiring Juan Gonzalez Chan Ho Park, Carl Everett and John Rocker. He also instituted changes at the top, replacing Oates and GM Doug Melvin with Jerry Narron and John Hart.

To no one’s great surprise, Texas had absolutely no chemistry—not to mention a continuing lack of quality arms. Despite a wealth of offensive talent, the Rangers were the laughingstock of the AL. Many fans felt Alex was getting exactly what he deserved.

Those who held that belief celebrated once again in 2003. The Rangers dropped to 70-89, a full 26 games behind the Oakland A’s in the AL West. Texas responded by bringing in Buck Showalter to run the show. By now, Alex was deeply frustrated. He didn’t see eye to eye on a variety of issues with his new skipper, but they managed to survive the year without strangling each other. Alex had always been regarded by his peers as a good guy, an opinion shared by many in the media. When he maintained his composure through another awful year in Texas, his reputation grew.

That was evident when it came time for postseason honors. Despite the fact that the Rangers stopped playing meaningful games in June, Alex earned his first AL MVP. He also received the Player's Choice Award as the league's outstanding performer.

Though his average dipped slightly to .298, Alex pounded out 47 home runs, drove in 118, scored 124, and received another Gold Glove. (He also legged out a career-high six triples.) In turn, Alex became just the third player in more than 70 years to win three consecutive AL home run titles and the fifth since 1954 to top the league in homers, runs, and slugging (.600) in the same year.

Alex’s season was all the more remarkable considering how little protection he had in the lineup. Showalter had helped usher in a youth movement in Texas, and while Palmeiro was still around, the batting order featured mostly up-and-comers hoping to prove themselves in the majors. Hank Blalock developed into an All-Star, and Mark Teixeira showed flashes of brilliance, but Alex was the only bat in Texas that pitchers consciously avoided.

The strain of carrying a team with such a dismal future began to wear on Alex in 2003. The honeymoon was over in Arlington—attendance and viewership were both way down, Hicks was losing his shirt, and the opportunity to challenge for a championship was remote at best. Those factors, combined with Alex’s touchy relationship with Showalter, caused him to think about leaving the Rangers.

Only a few teams could afford him,. The Red Sox stepped up with the first reasonable offer. Texas was interested, but absorbing the bloated contract of Manny Ramirez ran counter to the team’s new focus on fiscal responsibility. Still, the clubs negotiated a workable deal, which hinged on Alex forfeiting part of his salary. That, of course, was one thing that the Players Association could not abide by. In effect, Alex was told that giving up even a portion of the money owed to him would open a Pandora’s box. When the deal fell through, he feared he was stuck with the Rangers.

That was until the Yankees entered the picture. In Alfonso Soriano, New York had just the sort of player Texas wanted: a cheap superstar who could put up similar numbers to Alex. Though the Rangers had to eat part of their MVP’s contract, they jumped at the offer. Alex joined the Bronx Bombers in February.

The media circus started from the moment the deal was announced, and it intensified once Alex reported for spring training. Much of the speculation centered on his friendship with Jeter. The Yankee shortstop had distanced himself from his buddy several years earlier when Alex made some unflattering comments about him in a GQ feature story. Now Alex—the league’s Gold Glove shortstop—would have to shift positions in deference to his old friend.

Surrounded by the best group of hitters in his career—including Jason Giambi, Bernie Williams, Jorge Posada , Hideki Matsui, Gary Sheffield and Jeter—Alex felt right at home in pinstripes. Though Yankee Stadium’s “Death Valley” would likely limit his production, he was ready to take advantage of the short right field porch in the Bronx.

The pressure of playing in the Big Apple seemed to have an effect on Alex early in the 2004 season. Adjusting to third base also added to his problems. At his best, Alex was marvelous. In May, he had three hits and stole two bases in an 8-7 win over the Angels. A week later, Alex made his return to Texas. Greeted by a loud chorus of boos, he silenced the crowd by blasting a two-run homer at his first at-bat against the Rangers.

As the campaign progressed, however, Alex struggled for consistency. His numbers looked good, but he was frustrated by his inability to stay relaxed. Too often, he was lunging at the plate, trying to do too much to impress New York fans. The Yankees, meanwhile, were on cruise-control and built a huge lead in the AL East.

New York manager Joe Torre tried to help Alex by shifting him in the batting order to two hole, behind Jeter and in front of Sheffield. Seeing more fastballs, Alex began to swing the bat better. In an August win over the Orioles, Alex hit a tape-measure home run, stole home and made a pair of great defensive plays. At the hot corner, he had quickly developed into one of the league's top glovemen.

Sitting comfortably in first for most the season, the Yankees began to feel the heat from the Red Sox in September. Though New York finished with a 101-61 record, three games ahead of Boston, the club had to sweat it out down the stretch.

In the playoffs, the Yanks faced off against the Twins in the ALDS. A good postseason performer with the Mariners, Alex regained his form against Minnesota. He got his biggest hit of the year—an RBI-double that drove home Jeter—in New York's extra-inning win in Game 2. When the Yankees took the next two, they advanced to the ALCS. Alex ended the series as one of the teams best hitters, including a .421 batting average, two doubles, a home run and three RBIs.

The scene was set for what promised to be a thrilling series against the Red Sox for the right to go to the World Series. The Yankees came out swinging in Game 1, battering Curt Schilling in a 10-7 win. They also took Game 2 behind a sparkling performance by Jon Lieber.

When the series shifted to Boston, it appeared the rout was on. The Bronx Bombers lived up to their reputation with a 19-8 blowout in Game 3. Alex enjoyed a huge night, going 3-for-5 with two doubles, a homer, three RBIs and five runs.

Down 3-0, the Red Sox battled for a win in Game 4, coming back against Mariano Rivera. They rallied again in Game 5 to stay alive, and this time Alex wore the goat horns. With a chance to drive home an insurance run late in the contest, he struck out on a pitch out of the strike zone.

Back home for Game 6, Alex and the Yanks struggled in a rematch against Schilling. With New York behind by two runs in the eighth, Alex came to plate with Jeter on first and squibbed a roller down the first base line. Bronson Arroyo fielded the grounder, and Alex swatted at his glove, knocking the ball loose. Jeter scored all the way from first, but the umpires gathered and called Alex out. The raucous Yankee crowd went silent, and New York wound up losing 4-2.

Game 7 was over as soon as it started. Veteran Kevin Brown has nothing for New York, and neither did Javier Vazquez in relief of him. The Red Sox rolled to a 10-3 victory. In the locker room afterwards, Alex talked of the embarrassment of blowing such a commanding lead. He shouldered much of the blame. Alex collected just two hits in his last 17 at-bats against Boston pitching.

Alex’s regular season stats were good enough, including a .286 average, 36 home runs and 106 RBIs. But when he failed to carry the Yankees when they needed him the most, the fans let him have it. The choke job against the Red Sox was not his fault alone, but questions arose immediately about his ability to come through in the postseason. Those whispers would haunt him for years to come.

The Yankees reloaded on offense for the 2005 campaign, but they remained thin in the pitching department. The team limped through first six weeks of the season and languished below .500. Torre responded with one of the best managing jobs of his career, and New York ended up eking out a division title. Journeymen Aaron Small and Shawn Chacon were instrumental down the stretch. Both pitched brilliantly, but like the rest of the Yankees, they seemed exhausted when the playoffs began.

Alex had the season the New York fans were expecting. He led the AL with 48 home runs, 124 runs and a .610 slugging average. A .321 average and 130 RBIs cemented his first MVP award in pinstripes.

New York’s pitching woes came home to roost in the Division Series against the Angels. The Yankees led in every game, but won only twice. Alex batted a meager .133 with just two hits and no RBIs. All winter, New York fans lambasted the reigning MVP, claiming his regular-season stats were meaningless when he flopped in October. Of course, they ignored the fact that without A-Rod, the Yankees might not have snagged a postseason berth.

New York powered to the top of the AL East once again in 2006, despite injuries to several of their power hitters. Alex stayed healthy and turned in an excellent year. He clubbed 35 homers and led the team with 121 RBIs. Still, he was criticized relentlessly by fans and the media for virtually anything he did wrong. He later said it was his most difficult season as a pro.

With the Red Sox having a down year, the path to the World Series seemed clear for New York. The Twins and Tigers looked like pretenders, and the Yankees believed they could always find a way to beat the A's in the playoffs. In Game 1 in the Division Series, the Yankees blew out the Tigers behind their newly christened ace, Chien-Ming Wang.

The rest of the series did not go New York’s way. The young Detroit hurlers overpowered the Yankees, and crafty Kenny Rogers shut them out with smoke and mirrors. The Tigers took three straight and then swept the A's to reach their first World Series in 22 years.

The Yankees went home with their tails between their legs again. Again, the fingers were pointing at Alex, who managed just one hit in four games. Jeter, meanwhile, murdered Detroit pitching. Alex had alternated between looking overanxious and overwhelmed. He certainly did not look like a $252 million player.

That fat contract had an interesting loophole. Following the 2007 World Series, Alex had the choice of opting out of his deal and becoming a free agent. It would mean leaving $91 million on the table, but with Boras calling the shots, anything seemed possible. The Yankees made a half-hearted attempt to extend Alex's contract, especially because Texas would be on the hook for a big bite if Alex agreed to stay. But questions still lingered about his ability to produce in the clutch. No one felt much urgency, at least publicly.

As if to answer the questions he faced heading into the '07 campaign, Alex went on an historic tear in the season's opening month. He had trimmed down during the winter and made adjustments to his swing that increased his bat speed. That was evident in the fourth game of the year, when he homered twice against the Orioles, including a walk-off grand slam. After seven games, Alex had six home runs.

Alex hammered another walk-off homer on April 19 to defeat the Indians. Bronx fans gave him his warmest ovation as a Yankee. Four days later, he hit his 14th homer in 18 games—a record for that time span. It also marked his 23rd game in a row with a hit. Alex finished April tied for the most home runs in baseball's opening month, and his 34 RBIs was one short of the major league record.

Alex, however, was the only Yankee hitting. The team soon found itself in last place, and sports radio hosts across the country began banging nails into the team's coffin. For a change, they left A-Rod alone—until a game in late May against the Blue Jays. Alex became the center of a new storm when he distracted a Toronto player trying to catch a routine pop-up by shouting something as he swooped past him on the basepaths. The old schoolyard trick led to four Yankee runs, but Alex was branded bush-league by many baseball fans.

The Yankees rode out the controversy and slowly clawed their way back into contention. Alex helped pace the club, as he continued to drive in key runs. On August 4, he hit the 500th home run of his career. Just eight days past his 32nd birthday, Alex became the youngest player ever to do so. He set the record the same day Barry Bonds hit his 755th homer.

A month later Alex homered twice in the same inning against his former Seattle teammates. On September 25, when he launched home run #50 of the year —a grand slam—he came only the fifth player ever to have a 50-homer, 150-RBI campaign. Alex finished the year leading the league with 54 home runs, 156 RBIs, a .645 slugging average and 376 total bases. He was a no-brainer pick for AL MVP.

The Yankees made the AL East race mildly interesting but ended up as the league's Wild Card. They faced the Indians in the Division Series. Cy Young Award winner C.C. Sabathia slammed the door on New York in Game 1, and New York let Game 2 slip away in a 2–1 extra-inning defeat. After winning Game 3, the Yankees dropped Game 4 and missed the World Series for the fourth year in a row.

A couple of weeks later, during the World Series, Alex announced that he was opting out of his Yankees contract. He drew heavy fire for the timing of this revelation, which precipitated a split between him and Boras. Alex had spent months claiming he wanted to finish his career as a Yankee. The news that he was testing the free-agent waters made him look rather disingenuous.

Meanwhile, the market was breaking against Alex, who reportedly was looking for $30 million a year. In November, he took matters into his own hands. Alex (partially on the advice of billionaire Warren Buffett) chose to bypass Boras and negotiate with the Yankees directly. The result was a 10-year, $270 million deal. If Alex breaks Bonds’ career home run mark in pinstripes, he stands to make even more in bonuses.

Facing the pressure of a new contract, Alex fell into a predictable trap. Pressing early in the 2008 season, he strained his right quadriceps and wound up on the DL. Alex returned to action in mid-May, and the Yankees won eight of 11 games. Other injuries, however, were simultaneously taking their toll on the club. New York entered the year relying on three young arms in the starting rotation—Joba Chamberlain, Phillip Hughes and Ian Kennedy. Only Chamberlain remained on the roster three months later. By then, staff ace Chien-Ming Wang had been lost for the season with a blown Achilles. New York never recovered. The Yankees finished 89-73 and far out of the playoff picture in the AL.

Alex ultimately produced representative numbers—a .302 batting average, 35 homers, 103 RBIs and 104 runs scored. But after July, he wasn’t much better than an average player. In fact, all the headlines made by Alex were the result of his behavior off the field. He and Cynthia divorced, and the proceedings became very ugly and very public. She accused him of infidelity, a claim bolstered by reports that Alex was involved in an affair with Madonna. The disintegration of his marriage had an impact on him.

Things didn't get any easier for Alex in the off-season. First came the release of The Yankee Years, a book written by Tom Verducci of Sports Ilustrated with the help of Joe Torre. Alex was taken to task. Among other things, he was ripped for being abnormally consumed with his public persona, hence the nickname A-Fraud.

Alex would have been ecstatic if The Yankee Years had been the extent of his winter of discontent. In January of 2009, rumors surfaced that he had tested positive for banned substabces during his time in Texas. The reports were made public in conjunction with a book being researched by Selena Roberts, another writer for Sports Illustrated. A-Rod was cornered. In an interview with Peter Gammons, he admitted his drug use, though he gave scant details about it. He also positioned himself as a victim, claiming Roberts had crossed ethical lines in her pursuit of his story. Those charges proved to be false.

Reaction to Alex spanned the spectrum. Some cast him as baseball's ultimate villian. Others applauded his courage for coming clean. Alex subsequently apologized to Roberts and then held a press conference to further explain himself. With several teammates in attendance, he revealed that a cousin had spearheaded his use of performance enhancers and offered as many specifics as he could remember. Alex blamed himself for his predicament and said again and again that he had been "young and stupid." Some would still characterize him that way. Indeed, the New York daily News has since reported that has long known Angel Presinal, a trainer banned in MLB clubhouses because of his link to steroids.

When A-Rod became a Yankee, he had a special opportunity to write his own Hall of Fame legacy. In five years, he had won two MVP awards and set numerous records. Yet the big prize was still missing. Until Alex delivered a championship, many baseball fans—particularly those in New York—would consider his career incomplete.

As 2009 began, things went from bad to worse. Having admitted his dalliance with performance-enhancingdrugs, he now had to face news from doctors that the soreness he felt in hip prior to the World Baseball Classic was a cyst and torn labrum that required surgery. Alex chose to undergo a stopgap arthroscopic procedure that would enable him to return to the field by June. Another, more extensive procedure would likely be needed after the season.

Alex was back in the lineup on May 8, and not a moment too soon. The Yankees were struggling to stay at .500. Almost immediately, their offense was transformed. Alex slotted behind newcomer Mark Teixeira, who was starting to heat up after a slow spring. Together they powered the Yankees back into the AL East race. Alex hit dramatic ninth-inning homers against the Twins and Phillies in May. By mid-June, the Yankees were challenging the Red Sox for the division lead.

Alex finished the regular season with a record-setting bang. In an unforgettable sixth inning he launched a pair of home runs against the Rays—a grand slam and a three-run shot—to set an AL record with seven RBIs in an inning. The final homer was his 30th in an abbreviated season and accounted for his 100th RBI. That gave him a record 12th straight 30–100 campaign.

As the Yankees geared up for the playoffs, fans girded themselves for another classic A-Rod postseason swoon. In New York’s last three ALDS disappointments, Alex had been a black hole in the middle of the lineup. But he seemed like a different player—a player who had been humbled by public embarrassment and injury early in the year and who was now flying somewhat under the radar. Could A-Rod actually learn to relax and have fun in the playoffs?

The answer was a resounding yes. In the opening game of the ALDS, Alex stroked a pair of two-out RBI singles against the Twins. In Game 2, he crushed a game-tying homer in the ninth off closer Joe Nathan, as the Yankees won again. Alex hit another game-tying homer in Game 3, and the Yanks swept the series. All told, he batted .455 with six RBIs in three games.

The Angels had no better luck getting A-Rod out. In Game 1, he went 1-for-2 with a walk, sac fly and RBI in a 4–1 win. In Game 2, a wild extra-inning affair, Alex came to bat against closer Brian Fuentes with the Yankees trailing 3–2 in the bottom of the 11th. He laced a screaming line drive to right that cleared the fence and knotted the score. The Bronx Bombers won two innings later. In his first five playoff games, Alex had saved the Yankees from defeat three times.

Alex went 3-for-4 in a 10–1 wipeout of Anaheim in Game 4, scoring three runs and driving in two. The Yankees wrapped up the pennant in Game 6, and Alex was right in the thick of things. He reached base all five trips to the plate, with two hits and three walks. He drew a free pass with the bases jammed in the fourth inning, giving the team a lead it would not relinquish. Alex, who batted .429 against the Angels, was now just four wins away from the crowning achievement of his career.

In the World Series against the Phillies, it appeared that Alex was back in the outhouse. Philly’s pitchers fanned him six times in the first two games. But in Game 3, with the series knotted 1–1, Alex lined a pitch to right field that was initially ruled a double. A review of the play showed that the ball had hit a TV camera behind the fence, and it was ruled a homer. The hit rattled starter Cole Hamels, who had held the Yankees scoreless to that point, and narrowed the score to 3–2. New York took the lead an inning later and held it for an 8–5 comeback win.

Game 4 saw the Yankees blow a 4–2 lead in the eighth inning, as the Phillies seemed poised to even the series. In the top of the ninth, closer Brad Lidge retired the first two Yankees, but Johnny Damon scratched out a single. Lidge then hit Teixeira. After getting ahead of Alex, Lidge tried to beat him inside with a fastball. Alex turned on the pitch and lined it against the leftfield fence for a two-run double. He scored moments later on Jorge Posada’s long single. The Yankees took a commanding series lead with a 7–4 victory.

New York failed to wrap up the series in Game 5, losing 8–6. Alex hit a pair of doubles in the game, the second chasing Cliff Lee and triggering a comeback that saw the Yankees come up just short of another thrilling win. A-Rod was on deck when Teixeira struck out to end the ninth with Damon on second base.

Alex got his ring two nights later back in the Bronx, as the Yankees won Game 6, 7–3. He contributed a hit, two walks, two runs and a stolen base. Back in the lineup as the DH, Hideki Matsui, batting behind Alex, drove in a record-tying six runs.

Afterwards, Alex could hardly express his joy. When asked what was different about this postseason, he said that instead of trying to carry the club on his shoulders, he just felt like “one of the guys.” Of course, just the opposite is true. Since the postseason expanded from two tiers to three, few if any players have produced the raw numbers and dramatic clutch hitting that A-Rod did in 2009. Of the Yankees’ 80 runs, he produced more than a third—27, to be precise. Time and again, with the team behind, he delivered the key hit or triggered stunning rallies.

In 2010, Alex was prepared to defend a world championship for the first time in his career. Before that happened he had to deal with some off-the-field issues, including an FBI investigation into Anthony Galea, a Canadian doctor who was implicated in the illegal importation of performance enhancing drugs. Galea had worked with Alex during a previous rehab, but the authorities cleared the slugger of any wrongdoing.

The season itself got off to a shaky start for Alex, who waited until April 17th before launching his first home run. He heated up in May, socking a pair of grand slams during the month and hitting a ninth-inning homer off Jonathan Papelbon in an 11–9 triumph over the Red Sox. A sore hip limited Alex’s mobility in June, forcing him to sit or DH on several occasions, and a sore thumb made swinging painful. Although his power numbers were below typical A-Rod mid-season levels, he was still hitting with men on base. At the All-Star break he was closing in on 70 RBIs.

Earlier in the campaign, Alex created a stir when he crossed over the mound while returning to first base after a long foul ball during a game in Oakland. A’s pitcher Dallas Braden challenged him after the inning and again after the game, but Alex dismissed the Oakland pitcher, saying he did nothing wrong and characterizing Braden as a nobody just looking for his 15 minutes of fame. A few weeks later, after Braden twirled a perfect game against the Rays, the press descended on Alex for comment prior to a meeting with the Red Sox at Fenway Park. He played it smart, thanking Braden for beating Tampa Bay. Later that evening, Alex made headlines of his own, blasting a long ball that tied him with Frank Robinson on the all-time home run list.

Alex went to Anaheim as a member of the AL All-Star team. Girardi kept him on the bench, partially to avoid injury and partially to have a big bat for a big spot late in the game. The NL took a 3–1 lead in the seventh inning, which held into the ninth. The perfect spot for an Alex would have been as a pinch-hitter for John Buck with one out and David Ortiz on first. Since Buck was the AL’s last catcher, however, Girardi was not allowed to pull him. Buck blooped a ball into right field, where Marlon Bird took it on a short hop and then spun and gunned out Ortiz at second for a bizarre force play. Giradri chose to let Ian Kinsler hit against Jonathan Broxton with two outs. He lofted a fly ball to center for the final out.

Has Alex restored his reputation? Of course, there are those who say that his career is permanently smeared. They refuse to forgive him for his indiscretions and will be happy to see him pay dearly for them. How will Alex be viewed as he nears the all-time home run mark? Will Hall of Fame voters think more than twice about placing him on their ballots? For Alex—someone so clearly concerned about his reputation—these are questions that will haunt him the rest of his life.

Whether Alex continues to be one of the guys, or one of the greats, it seems he will enjoy baseball and life for the first time in a long time—and chase some heady records with Yankee fans firmly behind him.

ALEX THE PLAYER

All you need to know about Alex as a player is that he is currently the best in the business. He is a terrific hitter, a solid fielder, and an intelligent baserunner. Lost in the highs and lows of his four seasons in pinstripes is the fact that he has swiped 88 bases for the Yankees.

When the Mariners and Rangers pushed him to hit more homers, Alex bulked up and added more lift to his swing. That had the desired effect, but it also caused his average to dip and his strikeouts totals to increase. With the Yankees, he abandoned this approach, and the results were phenomenal. No righty in New York history has hit for more power in the Bronx.

A consistent fielder who makes all the plays, Alex is not flashy or spectacular. Still, he always seems to get his glove on tough balls and nip fast runners with his throws. After an adjustment period at third base—more of a reaction position than shortstop is—Alex has found a comfort zone at the hot corner. He has abandoned any thought of returning to his old position.

Of course, you can't discuss Alex without mentioning his lack of success in the postseason. Ask fans in New York, and they'll tell you that this is a symptom of a much bigger problem—Alex never produces when the pressure is most intense. While that criticism is unfair, it underscores a fascinating phenomenon of Alex's career. For all his numbers, he isn't thought of as a leader—at least that's the public perception. Until Alex wins a World Series, it's likely he never will be.