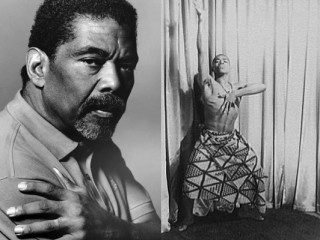

Alvin Ailey biography

Date of birth : 1931-01-05

Date of death : 1989-12-01

Birthplace : Rogers, Texas, United States

Nationality : American

Category : Arts and Entertainment

Last modified : 2010-07-14

Credited as : Dancer and choregrapher, founder of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, modern dance innovator

4 votes so far

Ailey was born to Alvin Ailey and Lula Elizabeth Cliff Cooper, and grew up picking cotton in rural southern Texas. His father left when Ailey was six months old. Ailey later considered the poverty and racism of 1930s Texas "an enormous stain" on his life. The rousing spirituals he heard in the region's Baptist churches, and the blues he listened to in its nightclubs, influenced Ailey in a more positive way. Ailey was twelve when he and his mother moved to Los Angeles, where he saw performances by Billie Holiday, Duke Ellington, the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, and dancer Katherine Dunham's revues Tropics and Le Jazz Hot. Years later, he met and collaborated with Ellington on My People and The River, and dedicated the dance Pas de Duke to him. He also restaged one of Dunham's revues with his own company. His mother married in 1945 and Ailey's stepbrother, Calvin, was born in 1953.

Ailey began studying modern dance at age eighteen with modern dance pioneer Lester Horton, whose integrated dance troupe was a rarity in its day. From Horton, Ailey learned a wide range of dance forms, including Japanese theater and Native American dances. When Horton died in 1953, Ailey took over the company, but his nontraditional education influenced him to develop his own dance style. Ailey's first choreographed pieces were Afternoon Blues in 1953, According to St. Francis (a tribute to Horton), La Creation du Monde (Creation of the World), and Mourning Morning, all in 1954.

Ailey danced in local nightclubs as part of the duo "Al and Rita" with fellow dance student Marguerite Angelos, who later achieved fame as the poet Maya Angelou. He became fascinated with the entire theatrical presentation of the dance—the music, costumes, lights, and themes. He studied languages in college at the University of California at Los Angeles (1949 to 1950), Los Angeles City College (1950 to 1951), and San Francisco State College (1952 to 1953), but dropped out to pursue dance in New York City. There, Ailey studied dance with modern dance legend Martha Graham, as well as Hanya Holm and Karel Shook. He appeared with Dorothy Dandridge in the film Carmen Jones (1954). He also performed with Harry Belafonte in Sing, Man, Sing (1956), and with Lena Horne in Jamaica (1957), and acted in plays, including Carefree Tree (1955), and the short-lived Broadway production Tiger, Tiger, Burning Bright (1962).

Ailey struggled to put together his own troupe, Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater (AAADT), which rehearsed wherever it could. His inaugural concert, featuring all Ailey originals, took place on 30 March 1958, and his Ode and Homage, Redonda, and Blues Suite won enthusiastic approval from the audience. Ailey danced his own Ariette Oubliee to Debussy music in a second concert that year. In his third concert, he unveiled Revelations, which remained a cornerstone dance for his troupe more than forty years later. The Ailey company of the 1950s and 1960s included many of Horton's former students. Ailey also choreographed pieces for other companies: Feast of Ashes for the Joffrey Ballet, three pieces for the Harkness ballet, and Anthony and Cleopatra for the Metropolitan Opera at Lincoln Center in New York City.

Revelations debuted in 1960 and was the product of endless research, countless hours of listening to music, and extensive soul-searching for Ailey. He recalled sleepy Sundays in church with his mother. The dance is built around spirituals sung by a live choir, including "I Been 'Buked, I Been Scorned," and follows a chronological flow of sorts. It is simple, direct, and powerful. The opening segment features the dancers dressed in simple, earth-tone costumes, signifying sorrow and a sense of rootedness in the soil. The opening stance, with a group of dancers close together, arms stretched to the sky, is among the most memorable in modern dance. It exemplifies the plainness and simplicity that gave Ailey's work an air of truth. The second section represents baptism, and dancers in pure white and blue tones. Ailey re-created onstage his own baptism, which had taken place in a snake-infested pond behind a church in his home-town. The final scene echoes the energy of a gospel church, with bright yellows and browns, the women carrying small fans. It has been said that more people have seen Revelations than any other ballet created in the twentieth century.

After two years of "station wagon tours," as Ailey called them, AAADT made a home for itself in a New York City YWCA in 1960. The troupe and its supporters converted the space into a 450-seat theater, rehearsal space, and costume house. It was called Clark Center for Performing Arts after the family that had donated funds to the renovation. At the Clark Center, Ailey found complete acceptance for what he was—an African American, a homosexual, and an incredibly talented and inspired artist. The place became a friendly hangout for African-American theater performers, dancers, and musicians. Six dancers filled the small stage for the first performance in November 1960, which included Lester Horton's Beloved and Revelations. Ailey was known for producing works by little-known choreographers, many of whom were competitive with him. He believed strongly that the work of choreographers who lacked their own companies would likely be lost without an effort to preserve those pieces, and that modern dance needed a living repository of both its classic and lesser-known dances.

Ailey's vision of what dance should be—"a popular form, wrenched from the hands of the elite"—appealed to increasingly larger audiences, although he always felt he had to make an extra effort to attract African Americans to the theater. He once estimated that only 20 percent of his audiences were black. He made a "social and political statement" with his primarily black dance troupe, as African Americans were not accepted in most other classical or concert dance companies. In the more militant 1960s, however, he was criticized for allowing whites and Asians to dance with his company.

The troupe found a more receptive audience in Europe, where it was met with hour-long standing ovations. Fueled in part by the universal popularity of the music in Revelations, the U.S. State Department invited the Ailey company to perform on an extensive and highly acclaimed 1962 tour of Southeast Asia, Ailey's first trip abroad. AAADT's international destinations also included Brazil and Africa, and, in 1970, Ailey's became the first American troupe to tour the Soviet Union.

Ailey managed the troupe's cash-strapped operations while dancing and choreographing, often disbanding the company when finances ran out, only to regroup. He lost dancers after every show because, he said, even faithful performers need to eat. Ailey constantly had to worry about money, and this, he felt, limited him artistically. He wanted the best in designers, music, and rehearsal spaces, and wanted to keep his dancers happy. It confounded him that the bulk of contributions went to classical ballet troupes.

In 1965 Ailey left the dancing to his dancers and the running of the business to a team of devoted supporters while he narrowed his focus to concentrate solely on choreography. By this time, the Ailey family included the dance theater, its training company, the Alvin Ailey Repertory Ensemble, and the Alvin Ailey American Dance Center. Dancer Judith Jamison joined the troupe in 1965, danced for fifteen years, then took over as artistic director.

Given to fits of temper and passionate outbursts, Ailey was notoriously difficult to work with. "I sacrifice everything to stay in dance," he wrote in his autobiography, and he expected those around him to do the same. He hired dancers who were temperamental, too, because he preferred their instincts and expressiveness. He chose round, full women along with the typical long, lean dancers, but detested the blank faces and cookie-cutter bodies that were the preference and trademark of the legendary ballet choreographer George Balanchine. "Come dancers," he would say as his dancers gathered around him the first day of a rehearsal for a new piece, to hear his ideas. His rehearsals were as much about acting as dancing, a method which took some getting used to.

Revelations launched a decade that was filled with a whirlwind of events and achievements for Ailey. He performed lead roles off and on Broadway, appeared with his company at the two most prestigious American dance festivals, and toured the world. He choreographed sixteen dances in the 1960s, including Quintet and the raw Masekela Langage, the latter about South African trumpet player Hugh Masekela, who was exiled for criticizing apartheid. The troupe performed at the White House for President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1968. Ailey choreographed The River for the American Ballet Theatre in 1970. His famous Cry, which was a birthday present to his mother and a tribute to all black women, debuted in 1971, and became an instant classic. He watched his company grow in size and prestige, even as it often mirrored the complexities of race issues in the United States.

The late 1970s saw the deaths of many of Ailey's close friends, including Duke Ellington and former Horton dancer Joyce Trisler. Ailey turned to drugs and was hospitalized for depression. He cleaned up his life, continued to choreograph, and kept the company together. By 1984, when Ailey and the troupe celebrated their twenty-fifth anniversary at the New York City Center, the Alvin Ailey Dance Theater had performed before some 15 million people in 44 countries on 6 continents. Ailey died of complications from AIDS, and is buried at Rose Hills Memorial Park in Whittier, California.

Writings on Ailey include his own Revelations: The Autobiography of Alvin Ailey (1995), as well as Jack Mitchell, Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater (1993), and Jennifer Dunning, Alvin Ailey: A Life in Dance (1996).