Barboncito biography

Date of birth : -

Date of death : -

Birthplace : northeastern Arizona

Nationality : Native American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2011-01-05

Credited as : Political and spiritual leader, led the Navajo resistance of the mid-1860s,

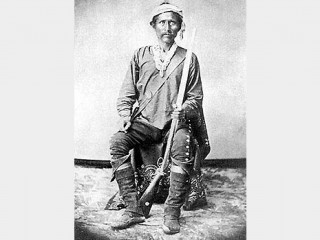

Barboncito (1820-1871) was a Native American chief who led the Navajo resistance of the mid-1860s. A staunch but peaceful opponent of white encroachment on Indian homelands, Barboncito was beloved among his people for his eloquence, his leadership skills, and his inspirational role as a religious singer. He is remembered for having signed the 1868 treaty that insured Navajos the lands on which they still live today.

Barboncito was born in 1820 to the Ma'iideeshgiizhnii ["Coyote Pass"] clan at Canyon de Chelly, in present-day northeastern Arizona. The mountains of this area produced a major stronghold for the Navajos, ensuring them a formidable defensive position. Barboncito quickly rose to become one of the council chiefs of the Navajo people.

When the United States occupied Santa Fe, in New Mexico territory, around the time of the Mexican War, the Navajos signed their first treaty with the white settlers. Barboncito was one of the chiefs to sign the Doniphan Treaty of 1846, agreeing to peaceful relations and beneficial trade with the whites. Despite the treaty, fighting continued between Navajos and whites because Doniphan had failed to obtain all the signatures of all the Navajo chiefs. Furthermore, the U.S. Army did not possess sufficient military strength to quell skirmishes between Navajos and nearby Spanish-Mexicans, who sought to enslave the Indians. Although leaders on both sides tried to put an end to the traditional warfare, their efforts proved to be of no avail. Attacks and negotiations by U.S. troops sent mixed signals to Navajos, who believed the Anglo-American settlers were unlawfully seizing Indian land.

Barboncito, also known as "The Orator" and "Blessing Speaker," did not participate in these skirmishes. In the late 1850s, he acted as a mediator between the Navajos and the whites and argued for putting an end to the escalating warfare. Navajos and whites fought over the grazing lands of Canyon Bonito near Fort Defiance, located in what is now the eastern part of the state of Arizona. The Navajos had let their horses graze in these pastures for centuries, but the newcomers also wanted the lands for their horses. In 1860, U.S. soldiers slaughtered a number of Navajo horses, leading the Navajos to raid army herds in order to replenish their losses. The U.S. forces responded by destroying the homes, crops, and livestock of the Navajo people.

The Anglo-American attack on the Navajos forced Barboncito to action. He soon earned the war name Hashke yich'i' Dahilwo ["He Is Anxious to Run at Warriors."] He led over 1,000 Navajo warriors in a retaliatory attack on Fort Defiance. The great skills of Barboncito nearly won them the fort, but he was driven off by the U.S. Army and pursued into the Chuska Mountains. In the mountains, the U.S. troops were unable to withstand the Navajo hit-and-run attacks.

Stalemated, Indians and whites sat down at a peace-council once again. Barboncito, Manuelito, Delgadito, Armijo, Herrero Grande, and 17 other chiefs met Colonel Edward R. S. Canby at Fort Fauntleroy, 35 miles south of Fort Defiance. They all agreed to the terms of a treaty in 1861. For a time, the Navajos and the whites tried to forge the bonds of friendship. Despite the treaty, an undercurrent of distrust caused conflict between the two groups to continue.

When the military diverted most of its forces east for the Civil War, the Navajos increased their efforts at what the whites considered to be "cattle-rustling and general marauding." The United States led an extensive campaign to "burn-and-imprison" the Navajos, administered by Colonel Christopher "Kit" Carson and Ute mercenaries, traditional enemies of the Navajos. Barboncito made peaceful overtures to General James H. Carleton, Carson's commanding officer, in 1862, but the assault against the Navajo people dragged on.

When this ruthless practice proved unsuccessful, Carleton ordered Carson to bodily move the entire nation of Navajo clans from their homes in the Arizona area to a region known as Bosque Redondo, in the arid lowlands of southeastern New Mexico—all despite protests from the Indian Bureau and Carson himself. Carleton is widely quoted as having said that he aimed to transform the Navajos from "heathens and raiders" to "settled Christians" under the watchful eye of troops stationed at nearby Fort Sumner.

Carleton met with Barboncito and other chiefs in April 1863. He informed the Navajos that they could prove their peaceful intentions by going to Bosque Redondo. Barboncito replied, as quoted in Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: "I will not go to the Bosque. I will never leave my country, not even if it means that I am killed." And despite army efforts to force him from his home, Barboncito stayed.

Barboncito led the resistance movement at Cañon de Chelly against Carson and the whites with the aid of Delgadito and Manuelito. Again, Carson launched a scorched earth campaign against the Navajos and Dinetah ["Navajo Land"]. Carson destroyed fields, orchards, and hogans—an earth-covered Navajo dwelling—and he confiscated cattle from the Continental Divide to the Colorado River. Though only 78 of the 12,000 Navajo people were killed, Carson's efforts crushed the Navajo spirit. By 1864, he had devastated Cañon de Chelly, hacking down thousands of peach trees and obliterating acres of corn fields. Eventually, a shortage of food and supplies forced the Navajos to surrender their sacred stronghold.

That same year, the "Long Walk" began, in which 8,000 Navajo people—two-thirds of the entire tribe—were escorted by 2,400 soldiers across 300 miles to Bosque Redondo, New Mexico. Almost 200 of the Indians died en route. The remaining 4,000 Navajos escaped west with Manuelito, who eventually surrendered in 1866 (two months before Barboncito). Barboncito was the last Navajo chief to be captured and led to Bosque Redondo. Once he found conditions there worse than imagined, he escaped and returned to Cañon de Chelly, but he was recaptured.

The "Long Walk" to Bosque Redondo was horrifying and traumatic for the Navajos. Disease, blight, grass-hoppers, drought, supply shortages, infertile soil, and quarrels with Apaches plagued the tribe. An estimated 2,000 people died of hunger or illness at the relocation settlement. As a ceremonial singer with knowledge of his people's ancient beliefs, Barboncito knew that it went against the wisdom of tradition for the Navajo to leave their sacred lands, to cross the rivers, or to abandon their mountains and shrines. Forced to do so—forced to become dependent on whites for food and other supplies—was spiritually destructive for the Navajo tribespeople and for Barboncito. He stayed as long as he could in the sacred lands, but on November 7, 1866, he led his small band of 21 followers to Bosque Redondo.

During their stay, Barboncito led ceremonies that the Navajos believed would help them to return home. The most frequently practiced ceremony of that time was called Ma'ii Bizee naast'a ["Put a Bead in Coyote's Mouth"]. According to historical records, the Indians formed a large circle with Barboncito and a female coyote, facing east, in the center. Barboncito caught the coyote and placed in its mouth a white shell, tapered at both ends with a hole in its center. As he set the coyote free, she turned clockwise and walked westward. This was seen as a sign that the Navajo people, the Dine, would be set free.

In 1868, Barboncito, Manuelito, and a delegation of chiefs traveled to Washington, D.C., after General Carleton had been transferred from Fort Sumner at Bosque Redondo and could no longer inflict his policies on the Navajo. Barboncito was granted great status by the whites—more authority than would have been accorded him by tribal custom. He played a leading role in negotiations with General William T. Sherman and Colonel Samuel F. Tappan, telling them that the creator of the Navajo people had warned the tribe never to go east of the Rio Grande River. He explained the failures of Bosque Redondo: even though they dug irrigation ditches, the crops failed; rattlesnakes did not warn victims away before striking as they did in Navajo Country; people became ill and died. Barboncito told the white negotiators that the Navajos wished to return home.

However, the U.S. government was not inclined to return all their land to the Navajos. Sherman provided Barboncito and the other chiefs with three choices: go east to Oklahoma (then known as Indian Territory), relocate in New Mexico and be governed by the laws of that territory, or return to a diminished portion of their original lands. The Navajos chose the last option. On June 1, 1868, the Navajo leaders, including Barboncito, signed a treaty with the U.S. government. As reprinted in Wilcombe Washburn's American Indian and the United States: A Documentary History, the agreement begins: "From this day forward all war between the parties to this agreement shall forever cease."

Although he was the last to surrender, Barboncito was the first to sign the document with his "X" mark. He died on March 16, 1871, at Cañon de Chelly, Arizona, having established himself as a distinguished chief and a skillful negotiator. The Navajo still live at Cañon de Chelly.

Biographical Dictionary of the Indians of the Americas, 2nd edition, American Indian Publishers, 1991.

Brown, Dee, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, Holt, 1970.

Dockstader, Frederick J., Great North American Indians, Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1977.

The Encyclopedia of North American Indian Tribes, edited by Bill Yenne, Crescent Books, 1986.

Handbook of the North American Indians, edited by William C. Sturtevant, Smithsonian Institution, 1983.

Insight Guides: Native America, edited by John Gattuso, Houghton Mifflin, 1993.

The Native Americans: An Illustrated History, edited by Betty Ballantine and Ian Ballantine, Turner Publishing, 1993.

Native North American Almanac, edited by Duane Champagne, Gale, 1994.

Waldman, Carl, Atlas of the North American Indian, Facts On File, 1985.