Bill Dudley biography

Date of birth : 1921-12-24

Date of death : 2010-02-04

Birthplace : Bluefield, Virginia, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2010-08-09

Credited as : Football player NFL, played for the Pittsburgh Steelers, and Washington Redskins

0 votes so far

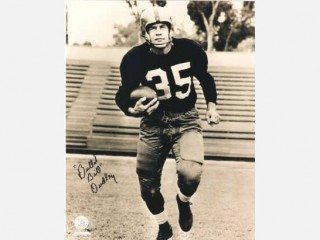

William McGarvey Dudley(December 24, 1921 – February 4, 2010) was born on Christmas Eve, 1921, in Bluefield, Virginia. Bill grew up playing pick-up football and honed his skills without any formal coaching in sandlot games. He was not particularly big and not particularly fast, but the game unfolded before him in ways that it did not for other boys, and he always seemed to be in the right place at the right time, both on offense and defense.

Bill’s football idol growing up was Michigan star Harry Newman, who came into the NFL in 1933 as an undersized quarterback and led the league in passing for the New York Giants. Bill’s own Newman-like ambitions were derailed his freshman year at Bluefield High, when he was denied a chance to try out for the team because no uniform was small enough to fit him. He stood just over five feet at this point, and weighed 100 pounds soaking wet. Having had his body rejected, Bill decided to build up his mind. He read everything he could find on football, including the late Knute Rockne’s books cover to cover.

Bill made the varsity as a sophomore, becoming the team’s punter and placekicker. By his junior year, Bill tipped the scales at 110 pounds and was approaching his ultimate playing height of 5-9. He saw some action during that autumn, but it was as a senior under new coach Marshall Shearer that his abilities were finally recognized. In fact, it was Coach Shearer who taught Bill to place-kick, and sportswriters would often comment on his unorthodox style. More obvious was Bill’s unusual throwing. He winged the ball to his receivers with a pronounced sidearm motion that would drive later coaches to distraction.

In his days as the “Bluefield Bullet,” however, no one was complaining. Although not blessed with great speed, Bill started quickly, ran elusively, changed directions almost intuitively, maneuvered behind blockers, and often spun away from would-be tacklers. In his final high school game, Bill scored his team’s only touchdown against Princeton High. Later, with the score knotted at 7–7, he drove his team down the field in the closing minutes to set up his own game-winning 35-yard field goal. The jubilant crowd poured out of the stands and carried him off the field.

Dreaming of playing college football, Dudley—who was now up to 150 pounds—got only one scholarship offer. Coach Shearer helped persuade Virginia Coach Frank Murray to recruit his determined protégé as an extra-point specialist. As a result, Bill received a $500 grant, out of which he paid for room, board, and books. He launched his college career as a 16-year-old tailback and kicker in 1938.

In 1939, Bill saw some action for the Cavaliers. He rushed for 194 yards, caught seven passes for 88 yards, and completed 16 of 41 attempts for 167 yards. Bill also punted 12 times for a 34-yard average and returned 12 punts and kickoffs for a total of 262 yards. Bill scored on two touchdown runs and added nine PATs for 21 points. On defense he played safety. The Cavs went 5-4 on the season.

The next season Bill won the regular punting job and booted 73 balls to lead the nation. He began as the team’s fifth back but, due to a teammate’s injury, logged enough time to catch nine passes, run the ball 106 times for 469 yards, and complete 67 of 140 passes. Including his punt and kickoff returns, Bill accounted for more than 1,700 yards for a lackluster 4-5 squad.

In 1941, Virginia switched from the single wing to the T-formation, and Bill became a star. He topped the nation’s major colleges with 134 points (18 TDs, 23 PATs, one field goal) and in total yards with 2,441—including rushing, receiving, interceptions returned, and punt and kickoff runbacks. He also completed 57 passes for 856 yards. For his efforts, Bill became his school’s first consensus All-American. In addition, he won the Maxwell Award, and received the Washington Touchdown Club's Camp Memorial Trophy as the outstanding college football player of the year. The Cavaliers went 8–1, losing only to Yale, 21–19.

Bill’s greatest performance as a senior came against the University of North Carolina—a team Virginia had not beaten since 1932. The Cavaliers vanquished the Tar Heels in Chapel Hill, 28-7, with Bill scoring three touchdowns, passing for another, and kicking all four extra points. He opened the scoring with a 67-yard pass play for the first touchdown; ran around end for more than 60 yards to score another TD; scored off a fake punt when he ran, dodged, ducked, and twisted for 89 yards; and then drove three yards up the middle for his third score. He also handled all the punting duties (averaging 42 yards), passed for 117 yards, carried the ball from scrimmage for 215 yards, and, of course, played defense, making several tough tackles and intercepting one pass.

“That was kind of the ‘big game’ of the year,” Bill remembered, “because we hadn’t beaten North Carolina in nine years. This was the ninth year, and they had a good football team.

“I scored a lot of points," he continued, talking about that '41 season, “but a lot of people forget that we only allowed something like 40-some points scored against us all year. And 21 of those points were scored by Yale in one ball game.

“We had a very good defensive football team. North Carolina only scored once, VMI scored twice, and I think that was it.”

After the season, Bill traveled to New Orleans and starred in the East-West Shrine game, intercepting four passes and throwing for his team’s only touchdown in a 6-6 tie. By the time he graduated in June of 1942, World War II had begun and he had aspirations of becoming a Navy pilot. According to Bill, he never planned to play pro football. In fact, the NFL was barely on his radar.

“The Pittsburgh Steelers drafted me number one,” he explained. “Of course, I knew about the University of Pittsburgh, but I didn’t know a thing about the Steelers. I knew a little bit about the Washington Redskins. We used to go up and see them play.

“But I never knew anything about the rest of the league, basically because it just didn’t enter my mind. College football and the bowl games were the big things.

“I was originally going to go in the Naval Air Corps. I was sworn in the Naval Air Corps in late May or early June of 1942. But when they started checking my papers, this came out later, they found out I had to have my parents’ consent, because I wasn’t twenty-one. So in the meantime, I went out to play in the College All- Star game in Chicago, and I signed a professional football contract. I played there with the Steelers mainly for the money.”

Bill signed for $5,000, and immediately injured both ankles in a preseason game against the Eagles. However, he was ready to play against Philadelphia on the NFL’s opening day in '42. Carrying on a trap play up the middle, “Bullet Bill” ran 55 yards for a touchdown, boosting the Steelers to a quick 7-0 lead. The Eagles won, 24-14, but Bill established himself as a tough and spirited big-league athlete. That first game foreshadowed his NFL career. He always played all-out and he would not hesitate to criticize a player who didn't give his best effort.

“I can’t stand a ballplayer that doesn’t put out,” Dudley later explained. “There’s no reason for a ballplayer to hang back at any particular time, particularly when they’re getting beat. That drives me up a wall!”

Pittsburgh lost its second game to the Washington Redskins, 28-14, even though Bill ran back a kickoff for a score. Inspired by their young star, however, the Steelers bounced back and won seven of their last nine contests. Art Rooney’s club, coached by Walt Kiesling, finished at 7-4, the franchise’s first winning record, and placed second in the East Division behind the 10-1 Redskins.

The stars of the team—including Dick Riffle, Curt Sandig, Milt Simington, Chuck Cherundolo, Walt Kichefski. Nic Niccolai—are forgotten now, most having had their careers snuffed out by World War II.

“We had a lot of fun,” Bill said of his first season. “Pittsburgh in ’42 was probably one of the most fun years I ever had. I didn’t know anything about Pittsburgh, the sun, it’s dark. All the steel mills were in full blast. You couldn’t see the sun for the smoke.

“Probably we’d work out from one to three o’clock in the afternoon, and it was just overcast all morning long.”

Running out of the single wing, Bill was the NFL’s best tailback. He led the league in rushing with 696 yards, averaging 4.3 yards per carry, and scoring five touchdowns on the ground. He also completed 35 of 94 passes for 438 yards and two TDs, punted 18 times for a 32.0 mark, returned 20 punts for 271 yards, and ran back 11 kickoffs for 298 yards, scoring once against Philly. Bill was named the NFL’s top rookie, made the All-Pro team, and was edged by Don Hutson of the Green Bay Packers for the Most Valuable Player award.

Bill went right into the Army Air Corps after the 1942 season. Facing the draft in Lynchburg, he had enlisted earlier in September. But because of the large number of recruits, a three-month delay resulted, allowing him to finish his rookie season.

Along with thousands of other young Americans, Bill spent the next two years in the service. He went through basic training in Florida and various flight schools in Texas. At Randolph Field he was asked to play football, which was deemed “essential” to the war effort as a morale booster. Bill agreed. In 1944 his team went 12-0. He was named MVP, and he made the All-Service squad.

Bill was shipped to the Pacific near the war’s end, and he was able to fly two supply missions. Upon his return to Hawaii, the Army’s top brass co-opted him into playing in three football games against All-Star teams in the fall of 1945. His reward: he could go home on a two-day flight, as opposed to enduring a six-week voyage by troopship.

That fall Bill returned to Pittsburgh, shared an apartment with center Si Titus, and played the last four games of the '45 season. Against the Chicago Cardinals at Forbes Field, he flashed his prewar form, running for two touchdowns and kicking two points-after in a 23-0 victory, only Pittsburgh’s second win in a 2-8 season under Coach Jim Leonard. Bill scored once more as the Steelers dropped their last three games. Still he finished with 20 points—more than any other Steeler in 1945. In addition, he rushed for 204 yards, connected on 10 of 32 aerials, ran back five punts for 20 yards, and returned three kickoffs for 65 yards.

In 1946, the Steelers welcomed austere, defensive-minded Jock Sutherland as their new coach. He was the best known football personality in town, having built the Pitt Panthers into one of the country’s toughest teams. A rift soon developed between Bill and Sutherland. During one passing drill at preseason camp, the coach, who made sarcastic comments about Bill’s sidearm passing motion, criticized his star for suggesting that it would be easier to complete passes if the defensive squad wore different color jerseys than the offense. The source of the friction may have been Bill’s penchant for admonishing teammates who put forth less than a full effort. Sutherland felt this was undercutting his authority.

Whatever the problem, it did not affect Bill’s performance during the season. His explosive 1946 campaign is still remarkable. Pittsburgh, running the single wing under Sutherland, tied Washington for third place with a 5-5-1 record. Had they won their last two games (tight losses by scores of 7–0 and 10–7), the Steelers would have edged the Giants for the Eastern title. Bill accounted for an enormous chunk of the club’s production. He scored 48 points and led the league in three different categories: rushing (604 yards), interceptions (10), and punt returns (27, good for a 14.0 average). For his outstanding season, Bill was named All-Pro as well as the NFL’s Most Valuable Player.

Bill endured a back injury in '46, and suffered a knee injury in the season-ending loss to the Eagles. Sutherland’s insistence on playing him through the sometimes obvious pain hurt the team in a couple of games, particularly a loss to the Lions, during which Bill was unable to cover the Detroit receivers.

“Sutherland was the best coach I ever played for,” Bill said. “But if you’re a football coach and can’t get along with a good football player, there’s something wrong.”

Fed up with Sutherland’s constant sarcasm and exhausted from his iron man performance, Bill announced his retirement.

“Playing the single wing, I figured, particularly in 1946, that I played about three years of football in one year,” he observed. “I was on the field almost 60 minutes, and doing everything. But that’s what I was capable of doing, and that’s probably one of the reasons I was able to stay in the league. But I did have a good head on my shoulders. You see, you play as much with your brains as you do with your body.”

Bill’s body took plenty of punishment in Pittsburgh’s single wing. He got hit so hard and gang tackled so often that other teams called him Flat Top after the Dick Tracy character.

Bill secured a position coaching the backfield for the University of Virginia in 1947. At that point, Pittsburgh traded his rights to Detroit for a couple of warm bodies and draft picks. Bill changed his mind about the NFL when the Lions offered him a guaranteed three-year contract at $20,000 a season—the highest salary since Red Grange played in the Roaring Twenties. The Bullet decided again to give football his best shot. “When I went to Detroit, I had a contract that was guaranteed for three years,” he reminisced. “At the end of the three-year period, if I didn’t play, I was guaranteed one year of coaching.”

A player’s player, Bill was unanimously elected captain by his teammates for each of his three seasons in Detroit, where his determined play became the heart of the Lions. Although the team did not have enough talent to fashion a winning season during Bill’s tenure, he led the club in scoring each year.

His first season the Lions, the team finished 3–9 under Gus Dorias. Bill shared the Detroit backfield with fullback Camp Wilson and quarterbacks Roy Zimmerman and Clyde LeForce. He ran for 302 yards and two touchdowns, and scored seven more TDs on 27 pass receptions. On October 19, Dudley returned a punt against the Bears for 84 yards and a touchdown, a play which is still one of the longest in franchise history.

Under Bo McMillin in 1948, Detroit wound up in the NFL West cellar again with a 2–10 mark. Nagged by injuries, Bill accounted for only 97 rushing yards, but scored six touchdowns as a receiver. In 1949, again under McMillin, Bill scored three TDs on the ground, two through the air, and one on a punt return. He also handled Detroit’s punting and placekicking duties, sending five field goals and 30 PATs through the uprights for a team-leading 81 points. Meanwhile, rookie Frank Tripucka jazzed up the offense and Bob Mann led the NFL in receiving yards to lift the Lions into fourth place with a 4–8 record.

After the season, the Lions dealt Bill to Washington. “Bo traded me to the Redskins, feeling that I might want to exercise that contractual right, you see, as a coach,” he recalled. “I was just getting ready to work for the Ford Motor Company. I worked for them one year in the off-season."

Bill, now 29, moved to Lynchburg, Virginia, and drove to Washington, where he would play the 1950, 1951 and 1953 seasons. Each year he led the Redskins in scoring. By that time, however, his knees were giving him more problems. Partly as a result, he spent the 1952 campaign as the backfield coach for Yale University.

The '50 Redskins were led by veteran Sammy Baugh. He lined up in the backfield with Bill, Charlie Justice, and fullback Rob Goode. Thjough deep threat Hugh Taylor was Baugh’s primary receiving target, Bill hauled in 22 passes, to go with 66 rushing attempts. He also handled Washington's kicking duties—he was a perfect 31-for-31 in PATs—and ran back a dozen punts.

On December 3, 1950, Bill again proved his big-play ability after a 60-yard punt by Pittsburgh’s Joe Geri. After running more than 30 yards to field the ball, he managed to stay in bounds at Washington's four-yard line. Running straight up the sideline, Bill startled the Steelers, who thought they saw the ball go out of bounds. Step-faking a would-be tackler, as if to cut to the middle, he hustled down the sideline behind gathering blockers and scored untouched on a 96-yard run.

The Redskins managed just three wins in '50, but improved to 5–7 in '51. The team dropped its first thee games, at which point George Preston Marshall canned coach Herman Ball. Chicago assistant Hunk Anderson was offered the job, but George Halas refused to let him go without getting a player in return. Marshall finally hired former Washington star Dick Todd to run the team, and the ’Skins went 5–4 the rest of the way, defeating the powerhouse Los Angeles Rams along the way. Bill contributed 398 rushing yards and 22 catches to what was essentially the same offense. He handled the bulk of the punt return work, about half the punting, and all of the placekicking. He hit seven of 10 field goal tries and 21 of 22 extra points.

After taking a year off, Bill, now 32, returned to Washington for one last season. Curly Lambeau had been hired to coach the team during his hiatus, and he whipped the ’Skins into a decent club. Gone was Baugh, replaced by Eddie LeBaron and rookie Jack Scarbath. Just when Washington fans thought Justice would never be the back he was in college, he began tearing it up and finished with 616 yards, third in the league behind Joe Perry and Dan Towler. With Leon Heath scoring touchdowns and throwing blocks, there was little for Bill to do in the Washington backfield except coach the runners, which he enjoyed immensely.

Bill was basically the team’s placekicking specialist at this stage, making half of his 22 field goal attempts and all of his 25 PATs. He also entered games as a DB on obvious passing downs. The Redskins went 6–5–1 in what would be the final season for both Bill and Coach Lambeau.

At the end of the season, physical wear and tear had accumulated to the point where the Bullet decided to retire. He had entered the insurance business in Lynchburg with his brother Jim in 1951, and worked with Home Life until switching to Equitable in 1961. During those years he also coached and scouted for the Steelers and, later the Lions. He remained active in the insurance business well into the 1990s.

Bill Dudley’s final numbers are more a reflection of his times than his performance. He scored 44 touchdowns in 90 NFL games, ran for a total of 3,057 yards and caught 123 passes for another 1,383 yards. He led the league in rushing yardage twice, in punt return yards twice, in kickoff return average once, in interceptions once, and in field goal percentage once. In all, he accounted for more than 7,700 yards of offense, made countless big tackles, recovered 36 fumbles, and intercepted 23 passes.

In 1956, Bill was enshrined in the College Football Hall of Fame. A decade later, he was part of the fourth class of Pro Football's Hall of Fame. Since 1990 the Downtown Club of Richmond has sponsored the Bill Dudley Award, which is given each year to the top college football player in Virginia. That honor is a fitting tribute to Dudley's outstanding dedication, performance, and work ethic, both on and off the gridiron.