Bobby Orr biography

Date of birth : 1948-03-20

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Parry Sound, Ontario, Canada

Nationality : Canadian

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2011-01-24

Credited as : Former ice hockey player NHL, played with the Boston Bruins,

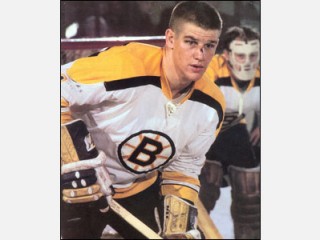

One of hockey's greats, Bobby Orr was the Boston Bruins' star player in the late 1960s to mid-1970s. He added to the position of defenseman the responsibility of offensive play as well.

Although he played for only nine full seasons (1966-1975) in the National Hockey League, and his name isn't found near the top of the list of all time high scorers, Bobby Orr of the Boston Bruins is widely regarded as one of the greatest hockey players of all time. "The great ones all bear a mark of originality, but Bobby Orr's mark on hockey, too brief in the etching, may have been the most distinctive of any player's.… He changed the sport by redefining the parameters of his position. A defenseman, as interpreted by Orr, became both a defender and an aggressor, both a protector and a producer," wrote E.M. Swift in Sports Illustrated.

Robert Gordon Orr was born in 1948 in Parry Sound, Ontario, a resort town on Lake Huron's Georgian Bay. Orr's father, Douglas, was a packer of dynamite at a munitions factory. His mother, Arva, worked as a waitress at a motel restaurant. The family included four other children, Ron, Patricia, Douglas, Jr., and Penny. Like most youngsters in Parry Sound, Orr began skating soon after he had learned to walk. Since, as Orr told People, "You don't skate without a stick in your hand," he also began playing hockey at an early age. Orr's extraordinary ability was evident from the start. By the time he was nine years old, he could hold his own in games with adults on his father's amateur team.

Shorter and thinner than most of his peers, the blonde, young blue-eyed Orr dazzled the coaches of Parry Sound's bantam league team with his skill, speed, and tenacity, rather than brute strength (even in his prime years in the NHL Orr was a solid but unprepossessing 5 feet, 11 inches, and weighed 175 pounds). In 1960, at age twelve, he led his bantam team to the final round of the Ontario championship. It was during this game that Orr began attracting the attention of professional hockey scouts. Several organizations showed interest, but the Boston Bruins, then the NHL's worst team, were most aggressive in pursuing Orr. To gain the boy's favor, the Bruins donated money to the Parry Sound youth hockey program, and team representatives made regular visits to the Orr family home. This persistence paid off. In 1962, fourteen-year-old Bobby Orr signed a

contract to play Junior A hockey for the Oshawa (Ontario) Generals, a Bruins farm team. In return, the Orr family received a small cash payment and a new coat of stucco for their house. At Oshawa, Orr's living expenses were paid for and he received $10 a week in pocket money. Realizing that the deal was not to his son's advantage, Douglas Orr retained the services of Alan Eagleson, a savvy young Toronto lawyer, to represent Bobby in future contract negotiations. "Sure I was homesick, and the family I lived with was tougher on me than my own folks," Orr later told People about his four years of playing junior hockey in Oshawa. "It was the way you served your apprenticeship. If you were good, you knew you'd turn pro at 18."

Orr played so well in junior hockey that the Bruins would have promoted him to the NHL a year sooner, if not for a league rule against players under 18 years of age. When Orr joined the Bruins in 1966, he arrived as the most highly touted rookie in years. He was also the highest paid rookie in NHL history, rumored to be earning somewhere around $25,000 a year, when the average NHL salary was $17,000 a year and the league's greatest star, the legendary Gordie Howe of the Detroit Red Wings, was earning about $50,000 annually. Showing the team spirit that would earn him the sincere affection and respect of his fellow-players, Orr urged his attorney Alan Eagleson to organize the NHL Players Association, which was instrumental in raising everyone's salary. By the end of his career, Orr was earning $500,000 per year, although this did not compare to the salaries earned by later players such as Wayne Gretzky. "People ask me if I'm upset when I see current players' salaries," Orr told the Boston Globein 1995. "I'm not upset. What upsets me is knowing Player A makes big money and seeing him give you three good games out of ten."

Orr entered the NHL with such hype, it seemed impossible for him to live up to the reputation that preceded him. Often called "unbelievable," Orr did not disappoint his fans. Although the Bruins again finished at the bottom of the then six-team NHL in the 1966-67 season, Orr won the Calder Trophy as Rookie of the Year. The following season the Bruins, enhanced by the acquisition of Phil Esposito, Ken Hodge, and Fred Stanfield from the Chicago Black Hawks, finished third in the Eastern Division of the expanded NHL and earned a place in the Stanley Cup playoffs. Orr won the Norris Trophy, awarded to the NHL's outstanding defenseman (he would win the Norris Trophy for the next seven seasons). The once pitiful Bruins were now among the most competitive teams in the league.

In the 1969-70 season, the Bruins won the Stanley Cup for the first time in 29 years, defeating the St. Louis Blues in four straight games in the playoff final. Orr secured the Cup for Boston by scoring a winning goal in an overtime period of the fourth game. In addition to the Norris Trophy, Orr won the Hart Trophy (for most valuable player in the NHL), the Ross Trophy (for Leading Scorer in the NHL), and the Smythe Trophy (for most valuable player in the playoffs). It was the first time a single player has one all four awards in one season. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the NHL was expanding rapidly into cities where hockey was not traditionally popular. The unprecedented exploits of Bobby Orr sold tickets in these cities and enabled hockey to become a truly national sport in the United States. "Orr remains the pivot figure in the game, the single charismatic personality around whom the entire sport will coalesce in the decade of the '70s, as golf once coalesced around Arnold Palmer, baseball around Babe Ruth, football around John Unitas," wrote Jack Olsen in the Sports Illustrated issue that named Orr the magazine's "Sportsman of the Year" for 1970.

The "Big, Bad Bruins" of the late 1960s and early 1970s, played a tough, messy game of hockey (as opposed to the elegantly classic moves of the Montreal Canadiens, the most frequent possessors of the Stanley Cup). Orr was remarkably polite and well-mannered off the ice but during a game he never shied away from a scrap. "We're not dirty. It's just that we're always determined to get the job done—no matter what it takes," Orr told Newsweek in 1969. An older and wiser Orr came to realize that brawling and belligerence set a bad example for children. In 1982, he made a short film called "First Goal" (sponsored by Nabisco Brands for whom he was doing public relations) advising young athletes, and their parents, that having fun is more important than winning.

After being eliminated by the Montreal Canadiens in the playoffs of the 1970-71 season, the Bruins came back to win the Stanley Cup again in 1971-72. Then the team's fortunes quickly began to fade. At the end of the 1971-72 season several top players, including flamboyant center Derek Sanderson, were lured away to the newly founded World Hockey Association and a number of good second-string players were lost in a further expansion draft. Orr stayed on with the Bruins, but knee injuries, which had plagued him since the start of his professional career, were becoming increasingly serious. "When you are young, you think you can lick the world, that you are indestructible … But around 1974-75, I knew it had changed. I was playing, but I wasn't playing like I could before. My knees were gone. They hurt before the game, in the game, after the game. Things that I did easily on the ice I could not do anymore," Orr explained to Will McDonough of the Boston Globe.

In 1976, a bitter contract dispute ended Orr's long-time relationship with the Bruins. He signed as a free-agent with the Chicago Black Hawks but knee problems kept him off the ice for all but a handful of games over two seasons. In 1978, he reluctantly announced his retirement. Having left Boston under strained circumstances, Orr was unprepared for the reaction he received from Bruins fans when his number 4 sweater was retired to the rafters of the Boston Garden in 1979. The outpouring of affection left him speechless and on the brink of tears. Similar emotion accompanied the closing ceremonies of the cavernous old Boston Garden in 1995, as Orr took one last skate on the Garden's ice. Perhaps only Ted Williams, the great Boston Red Sox slugger of the 1940s and 1950s, is held in as high esteem by New England sports fans.

Orr and his wife, Peggy, a former speech therapist, live in suburban Boston (with additional homes on Cape Cod and in Florida). They have two sons, Darren and Brent. Orr spends his time tending to a wide variety of business investments and charitable endeavors. He has no interest in coaching and would like to return to professional hockey as a team owner. "It was good that I retired so young," Orr told Joseph P. Kahn of the Boston Globe. "The adjustment period was difficult but at least I had things I could do. I have a great life now."