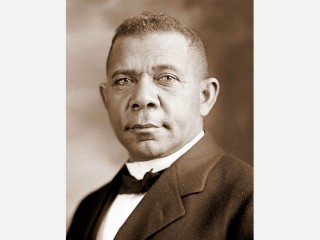

Booker T. Washington biography

Date of birth : 1856-04-05

Date of death : 1915-11-14

Birthplace : Roanoke, Virginia, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2010-07-09

Credited as : Political leader and author, ,

16 votes so far

Booker T. Washington was born near Roanoke, Virginia, at Hale's Farm, where his mother was the slave cook of James Burroughs, a small planter. His father was white and possibly a member of the Burroughs family. As a child Booker swept years and brought water to slaves working in the fields. Freed after the Civil War, he and his mother went to Malden, West Virginia, to join Washington Ferguson, whom his mother had married during the war. There young Washington helped support the family by working in salt furnaces and coal mines. He taught himself the alphabet, then studied nights with the teacher of a local school for blacks. In 1870 he started doing housework for the owner of the coal mine where he worked at the time. The owner's wife, an austere New Englander, encouraged his studies and instilled in Washington a great regard for education. In 1872 he set out for the Hampton Institute, a school set up by the Virginia legislature for blacks. He walked much of the way and worked menial jobs to earn the fare to complete the five-hundred-mile journey.

Washington spent three years at Hampton, paying for his room and board by working as a janitor. After graduating with honors in 1875, he taught for two years in Malden, then returned to Hampton to teach in a program for American Indians. In 1881, General Samuel Chapman Armstrong, the principal at Hampton, recommended Washington to the Alabama legislature for the job of principal of a new normal school for black students at Tuskegee. Washington was accepted for the position, but when he arrived in Tuskegee he discovered that neither land nor buildings had been acquired for the projected school, nor were there any funds for these purposes. Consequently, Washington began classes with thirty students in a shanty donated by a black church. Soon, however, he was able to borrow money to buy an abandoned plantation nearby and moved the school there.

Convinced that economic strength was the best route to political and social equality for blacks, Washington encouraged Tuskegee students to learn industrial skills. Carpentry, cabinetmaking, printing, shoemaking, and tinsmithing were among the first courses the school offered. Boys also studied farming and dairying, while girls learned cooking and sewing and other skills related to homemaking. Strong emphasis was placed on personal hygiene, manners, and character building. Students followed a rigid schedule of study and work and were required to attend chapel daily and a series of religious services on Sunday. Washington usually conducted the Sunday evening program himself. During his thirty-four-year principalship of Tuskegee, the school's curriculum expanded to include instruction in professions as well as trades. At the time of Washington's death in 1915 Tuskegee had an endowment of $2 million and a staff of 200 members. Nearly 2,000 students were enrolled in the regular courses and about the same number in special courses and the extension division. Among its all-back faculty was the renowned agricultural scientist George Washington Carver.

Although his administration of Tuskegee was Washington's best-known achievement, his work as an educator was only one aspect of his multifaceted career. Washington spent much time raising money for Tuskegee and publicizing the school and its philosophy. His success in securing the praise and financial support of northern philanthropists was remarkable. One of his admirers was industrialist Andrew Carnegie, who thought Washington "one of the most wonderful men ... who ever has lived." Many other political, intellectual, and religious leaders were almost as laudatory. Washington was also in demand as a speaker, winning national fame on the lecture circuit. His most famous speech was his address at the opening of the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta in September, 1895.

Later known as the Atlanta Compromise, the speech contained the essence of Washington's educational and racial views and was, according to C. Vann Woodward in his review of Louis R. Harlan's biography Booker T. Washington: The Making of a Black Leader, 1865-1901 for New Republic, "his stock speech for the rest of his life." Emphasizing to black members of the audience the importance of economic power, Washington contended that "the opportunity to earn a dollar in a factory just now is worth infinitely more than the opportunity to spend a dollar in an opera house." Consequently he urged blacks not to strain relations in the South by demanding social equality with whites. To the white members of the audience he promised that "in all things that are purely social we can be as separate as fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress."

The Atlanta speech, Woodward notes, "contained nothing [Washington] had not said many times before.... But in the midst of racial crisis, black disenfranchisement and Populist rebellion in the '90s, the brown orator electrified conservative hopes." Washington was hailed in the white press as leader and spokesman for all American blacks and successor to the prominent abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who had died a few months earlier. His position, however, was denounced by many black leaders, including civil rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois, who objected to Washington's emphasis on vocational training and economic advancement and argued that higher education and political agitation would win equality for blacks. According to August Meier, writing in the Journal of Negro History, those blacks who accepted Washington's "accommodation" doctrines "understood that through tact and indirection [Washington] hoped to secure the good will of the white man and the eventual recognition of the constitutional rights of American Negroes."

The contents of Washington's recently released private papers reinforce the latter interpretation of the educator's motives. These documents offer evidence that in spite of the cautious stance that he maintained publicly, Washington was covertly engaged in challenging racial injustices and in improving social and economic conditions for blacks. The prominence he gained by his placating demeanor enabled him to work surreptitiously against segregation and disenfranchisement and to win political appointments that helped advance the cause of racial equality. "In other words," Woodward posited, "he secretly attacked the racial settlement that he publicly sanctioned."

Among Washington's many published works in his autobiography Up From Slavery, a rousing account of his life from slave to eminent educator. Often referred to by critics as a classic, its style is simple, direct, and anecdotal. Like his numerous essays and speeches, Up From Slavery promotes his racial philosophy and, in Woodward's opinion, "presents [Washington's] experience mythically, teaches `lessons' and reflects a sunny optimism about black life in America." Woodward added, "It was the classic American success story, `the Horatio Alger myth in black.' " Praised lavishly and compared to Benjamin Franklin's Autobiography, Up From Slavery became a best-seller in the United States and was eventually translated into more than a dozen languages.

PERSONAL INFORMATION

Family: Original name, Booker Taliaferro; later added surname Washington; born into slavery, April 5, 1856, on a plantation near Hale's Ford, Franklin County, VA; died of arteriosclerosis and extreme exhaustion, November 14, 1915, in Tuskegee, AL; buried in a brick tomb made by students, on a hill overlooking Tuskegee Institute; son of Jane Ferguson (a slave); married Fannie Norton Smith, 1882 (deceased, 1884); married Olivia A. Davidson (an educator), 1885 (deceased, 1889); married Margaret J. Murray (an educator), October 12, 1893; children: (first marriage) Portia Washington Pittman; (second marriage) Booker Taliaferro, Jr., Ernest Davidson. Education: Hampton Institute, B.A. (with honors), 1875; Wayland Seminary, M.A., 1879.

AWARDS

A.M., Harvard University, 1897; LL.D., Dartmouth College, 1901; first black elected to Hall of Fame, New York University, 1945.

CAREER

Worked in the salt furnaces and coal mines of West Virginia as a child, and as a houseboy for General Lewis Ruffner, 1970-72; teacher at a rural school for blacks, Malden, WV, 1875-78; Hampton Institute, Hampton, VA, teacher and director of experimental educational program for Indians, 1879-81; Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute, Tuskegee, AL, co-founder, principal, and professor of mental and moral sciences, 1881-1915; writer. Founder of National Negro Business League, 1900, and National Negro Health Week, 1914; adviser to several U.S. presidents, including Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft, on racial and social matters; lecturer on racial and educational subjects.

WRITINGS BY THE AUTHOR:

* Black-Belt Diamonds: Gems From the Speeches, Addresses, and Talks to Students of Booker T. Washington, compiled by Victoria Earle Matthews, introduction by Thomas Fortune, Fortune & Scott, 1898, reprinted, Negro Universities Press, 1969.

* The Future of the American Negro (essays and speeches), Small, Maynard, 1899, reprinted, Negro Universities Press, 1969.

* (With N. B. Wood and Fannie Barrier Williams) A New Negro for a New Century, American Publishing House, 1900, reprinted, AMS Press, 1973.

* Sowing and Reaping, L. C. Page, 1900, reprinted, Books for Libraries, 1971.

* (With Edgar Webber) The Story of My Life and Work (autobiography), illustrations by Frank Beard, J. L. Nichols, 1900, revised edition published as An Autobiography by Booker T. Washington: The Story of My Life and Work, introduction by J. L. M. Curry, J. L. Nichols, 1901, another revised edition published as Booker T. Washington's Own Story of His Life and Work, supplement by Albon L. Holsey, 1915, reprint of original edition, Negro Universities Press, 1969.

* (With Max Bennett Thrasher) Up From Slavery: An Autobiography, A. L. Burt, 1901, reprinted, with an introduction by Langston Hughes, Dodd, 1965, reprinted, with an introduction by Booker T. Washington III and illustrations by Denver Gillen, Heritage Press, 1970, reprinted, with illustrations by Bart Forbes, Franklin Library, 1977, abridged edition, Harrap, 1929.

* Character Building: Being Addresses Delivered on Sunday Evenings to the Students of Tuskegee Institute by Booker T. Washington, Doubleday, Page, 1902, reprinted, Haskell House, 1972.

* (Contributor) The Negro Problem (articles), James Pott, 1903, reprinted, AMS Press, 1970.

* Working With the Hands (autobiography), illustrations by Frances Benjamin Johnston, Doubleday, Page, 1904, reprinted, Arno, 1970.

* (Editor with Emmett J. Scott) Tuskegee and Its People: Their Ideals and Achievements, Appleton, 1905, reprinted, Books for Libraries, 1971.

* Putting the Most Into Life (addresses), Crowell, 1906.

* (With S. Laing Williams) Frederick Douglass (biography), G. W. Jacobs, 1907, reprinted, edited by Ellis Paxson Oberholtzer, Argosy-Antiquarian, 1969.

* The Negro in Business, Hertel, Jenkins, 1907, reprinted, AMS Press, 1971.

* (With W. E. B. Du Bois) The Negro in the South: His Economic Progress in Relation to His Moral and Religious Development (addresses), G. W. Jacobs, 1907, reprinted, AMS Press, 1973.

* The Story of the Negro: The Rise of the Race From Slavery, two volumes, Doubleday, Page, 1909, reprinted, Negro Universities Press, 1969.

* (With Robert E. Park and Emmett J. Scott) My Larger Education: Being Chapters From My Experience (autobiography), illustrated with photographs, Doubleday, Page, 1911, reprinted, Mnemosyne Publishing, 1969.

* (With Robert E. Park) The Man Farthest Down: A Record of Observation and Study in Europe, Doubleday, Page, 1912, reprinted, with an introduction by St. Clair Drake, Transaction Books, 1984.

* The Story of Slavery, Hall & McCreary, 1913, reprinted, with biographical sketch by Emmett J. Scott and photographs from Tuskegee Institute, Owen Publishing, 1940.

* One Hundred Selected Sayings of Booker T. Washington, compiled by Julia Skinner, Wilson Printing, 1923.

* Selected Speeches of Booker T. Washington, edited by son, E. Davidson Washington, Doubleday, Doran, 1932, reprinted, Kraus Reprint, 1976.

* Quotations of Booker T. Washington, compiled by E. Davidson Washington, Tuskegee Institute Press, 1938.

* The Booker T. Washington Papers, thirteen volumes, University of Illinois Press, 1972-84, Volume I: The Autobiographical Writings, Volume II: 1860-1889, Volume III: 1889-1895, Volume IV: 1895-1898, Volume V: 1899-1900, Volume VI: 1901-1902, Volume VII: 1903-1904, all edited by Louis R. Harlen; Volume VIII: 1904-1906, Volume IX: 1906-1908, Volume X: 1909-1912, Volume XI: 1911-1912, Volume XII: 1912-1914, Volume XIII: 1914-1915, all edited by Louis R. Harlan and Raymond W. Smock.

Author of numerous monographs, including Education of the Negro, J. B. Lyon, 1900.

MEDIA ADAPTATIONS

Recordings--"Up From Slavery," read by Ossie Davis, Caedmon Records, 1976.