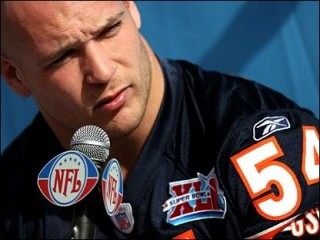

Brian Urlacher biography

Date of birth : 1978-05-25

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Pasco, Washington, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2010-08-20

Credited as : Football player NFL, currently plays for the Chicago Bears , won Super Bowl

1 votes so far

Brian Keith Urlacher was born to Brad and Lavoyda Urlacher on May 25, 1978, in Pasco, Washington. The young couple already had one child, a girl named Sheri; a second son, Casey, would follow. Lavoyda was just 16 when she married Brad, and by the mid-80s the two had drifted apart. When they divorced, she got custody of the kids. Scared and alone, Lavoyda moved her family to Lovington, New Mexico, a small town in the state’s southeast corner where her parents lived.

Lavoyda hoped for a fresh start. Lovington, which had as many oil fields as people, was by no means a thriving metropolis, but she had a support network there and finding work was fairly easy. Lavoyda split her time between three jobs, in a laundramat, grocery store and convenience store. Brian, Sheri and Casey sometimes saw more of babysitters than they did of their mother.

Six years after the Urlachers settled in Lovington, Lavoyda married Troy Lenard, a cowboy and oil field pipeliner. Lenard brought a sense of discipline to Brian’s life that the youngster embraced. He respected his stepfather’s work ethic. Brian also knew if he got out of line, he could expect a couple of whacks on the butt from the two-by-four Lenard dubbed “Uncle Henry.”

By this time, Brian had discovered sports. His favorites were football and basketball. Brian was a driven, energetic player who listened intently to his coaches. As a sophomore at Lovington High School, he earned time at wide receiver. Brian was fast, had good hands and wasn’t afraid to go over the middle. After the season, assistant coach Jamie Quinones introduced Brian to the weight room, which became the teenager’s home away from home. It was also about this time that he began to grow.

Over the next two years, Brian spouted five inches and packed nearly 60 pounds of muscle onto his frame. His combination of speed, size and power made him a monster on the gridiron. In his senior year at Lovington, he led the Wildcats to a perfect 14-0 record and the 3-A state championship. Head coach Speedy Faith never took him off the field. Brian caught 61 passes (15 for touchdowns), returned four punts and two kickoffs for scores, and also hit paydirt twice on running plays. He won all-state honors at receiver and safety.

Thanks to his exploits on the football field, Brian became Lovington’s most recognizable citizen. Despite his newfound celebrity, however, he maintained a low profile. Along with his best friend Brandon Ridenour, he didn’t follow the crowd and go out drinking on weekends. When he and his buddies partied into the pre-dawn hours, they were playing ping-pong and chugging chocolate milk.

Brian hoped to continue his football career at Texas Tech, located just across the state border, in Lubbock. Coach Faith helped out by piecing together a highlight reel and sending it to the Red Raiders. But Tech never came across with a scholarship. In fact, the only Division 1-A schools that recruited Brian were New Mexico and New Mexico State. Undeterred by the lack of interest in him, he choose to play for Dennis Franchione and the Lobos. For Brian, any chance to rise above his meager beginnings in Lovington was a golden opportunity.

Brian’s first two campaigns at New Mexico were uneventful. He converted to linebacker his freshman year and saw only sporadic game action. In the middle of a rebuilding plan with the Lobos, Franchione relied heavily on upper classmen, which left little room for an undersized defender like Brian. After a 6-5 record in 1996, New Mexico went 9-4 in 1997, good for first in the newly formed Mountain Division of the Western Athletic Conference. Though the squad was routed by Colorado State in the WAC Championship Game, it still received an invitation to the Insight.com Bowl (just the school’s second bowl bid since 1961). The Lobos fell to the Arizona Wildcats, who got 172 yards and three scores from Trung Canidate.

Buoyed by his success at New Mexico, Franchione moved on to Texas Christian (then eventually Alabama and Texas A&M). In his place, the Lobos hired UCLA defensive coordinator Rocky Long, a star quarterback at New Mexico in the 1970s.

ON THE RISE

The hiring of Long proved a stroke of good fortune for Brian. At UCLA, Long had developed an aggressive defensive scheme geared toward talented athletes who could make tackles all over the field. In turn, he helped turn safeties Reggie Tongue and Shaun Williams into big-time stars. In Brian, Long felt he had an even better physical specimen.

The coach’s first move was to switch his junior linebacker—who now stood a rock solid 6-4 and 235 pounds—to the freelancing “Lobo” position. Defensive end Ryan Taylor was then shifted to middle linebacker, while Barrett Garrison remained at nose tackle. With his three best defenders attacking opponents from the middle of the field, Long was confident the Lobos would do some damage.

On offense, New Mexico looked good, too. At quarterback, senior Graham Leigh, the WAC’s 1997 Offensive Player of the Year, was coming off a season in which he threw for 2,318 yards and 24 touchdowns. He also topped the team in rushing (528 yards, eight TDs). In the backfield were three more strong runners in Dion Marion, Lennox Gordon and Reginal Johnson. With Long implementing a West-Coast style offense, the Lobos figured to light up the scoreboard.

The ’98 season, however, did not go according to plan. Because of Leigh’s running ability, the coaching staff altered the offense to fit his abilities. The results weren’t good. New Mexico racked up decent yardage, but didn’t get into the end zone often enough. Injuries also decimated the team, as Long was forced to use 20 different starters on defense alone. While the Lobos beat Idaho State in their coach’s debut, they lost nine of their final 10 games to go 3-9.

Brian was one of the team’s few bright spots. A first-team all-Mountain West selection, he made an astounding 178 tackles on the season to lead the nation. Long hoped that Garrison and Taylor would be just as active as Brian, but he was the only defender who thrived in the coach’s system.

Over the summer, Brian worked with defensive coordinator Bronco Mendenhall on his pass coverage technique. During his two years at linebacker, he had refocused his approach to the game, losing touch with the skills of a good secondary player. In his estimation, he had dropped eight interceptions in 1998. He also felt his footwork and timing were in need of improvement.

Coach Long had a lot of work to do himself. Though the Lobos returned 42 lettermen, experts predicted the team would finish no better than seventh out of eight squads in the conference. The offense was part of the problem. Juco transfer Sean Stein was expected to be the starting quarterback, while sophomore Rishard Stafford, a converted wide receiver, won the tailback job in spring practice. The line, which featured two seniors and two juniors, and the receiving corps—led by Martinez Williams and Germany Thompson—were the two areas where Long felt confident.

On the other side of the ball, the coach fiddled with several positions. Lineman Casey Tisdale and Jeff Macrea were switched to linebacker, while a pair of sophomores, Scott Gerhardt and Derrell Moten, were plugged in at safety.

Of course, Brian was the key to the Lobo defense. Long, however, also believed his senior could contribute on offense and special teams. Given Brian’s size, speed and leaping ability, he was a perfect receiving target in the red zone, where he could out-jump smaller defensive backs on fade patterns. Long occasionally dropped Brian deep for kickoff and punt returns, too.

Once again in 1999, Brian delivered while his teammates didn’t. Long suffered through his second straight losing season, as the Lobos went 4-7. The problem was the third quarter—the team came out of the locker room flat time and time again. In fact, if Mew Mexico had just played it even during those 15 minutes each contest, the Lobos could have reversed their record.

Brian, by contrast, was spectacular from the season’s opening snap. Though opponents often tried to run away with their offensive schemes, he found a way to get into just about every play. For the year, he registered 148 tackles, including 21 in a 52-7 loss at Utah. He also forced five fumbles and recovered three others. None was more memorable than the loose ball he pounced on against San Diego State. With the Lobos looking for their first MWC victory, Brian returned a fumble 71 yards to seal the victory. He also made the key play in a 33-28 upset of Air Force, flattening running back Matt Rillos with a crushing hit near the goal line.

On offense, Brian was a force, too. Of his seven receptions, six went for touchdowns. He also averaged 15.8 yards on 10 punt returns.

One of three finalists for the Jim Thorpe Award, Brian was selected a first team All-American by the Walter Camp Foundation, Football Writers Association of America and Associated Press. In addition, he took home honors as his conference’s Player of the Year and even got some Heisman Trophy consideration. (He placed 12th in the balloting.)

Once the season ended, Brian concentrated on raising his profile for the NFL draft. Based on athletic ability alone, he was rated among the top 10 players available. Knowing that pro scouts projected him as a linebacker, he hit the weight room harder than ever. The work paid off—at the Senior Bowl he notched five tackles, including one for a loss, and was named the game’s MVP.

Brian weighed in at 258 pounds at the NFL Scouting Combine in Indianapolis. Coaches were impressed with his chiseled frame—especially after he bench pressed 225 pounds 27 times—but wondered whether he had lost any speed. When he logged a sub-4.6 40, all questions were answered.

On draft day, Brian awaited a phone call from one of two teams, the Cardinals or Bears. Both clubs needed an impact player on defense, though Arizona also had its eye on Thomas Jones, the flashy running back out of Virginia.

When their spot came up, the Cardinals opted for offense and took Jones, allowing Brian to fall into Chicago’s lap with the #9 pick. He became New Mexico’s first first-round pick since Robin Cole was taken by the Pittsburgh Steelers in 1977. Brian wasted no time getting on board with the Bears, signing a five-year deal worth $8 million. The team announced the rookie would start at strongside linebacker.

Brian joined a club searching for an identity. By most accounts, second-year coach Dick Jauron was making due with one of the least talented rosters in the league. On offense, his choice of quarterbacks came down to Jim Miller and Cade McNown, while his leading runner going in 1999 was Curtis Enis, a highly touted back out of Penn State who had yet to live up to his press clippings. The team’s biggest threat was receiver Marcus Robinson, who emerged from nowhere to corral 84 passes for 1,400 yards and nine TDs.

Chicago had even more problems on defense. The Bears addressed one of their shortcomings—a poor pass rush—by signing Phillips Daniels. They also inserted second-round pick Mike Brown, out of Nebraska, into the secondary. With the addition of Daniels, Brown and Brian, defensive coordinator Greg Blache thought his unit would show improvement in 2000.

But Brian initially had a hard time adjusting to life as an NFL linebacker. He commited too many mental mistakes, often getting caught out of position because of them. Ironically, Brian’s celebrated versatility was working against him in the pros. Keeping his responsibilities straight was almost impossible. Jauron had no choice but to replace him on the outside with Rosevelt Colvin.

MAKING HIS MARK

In Chicago’s season opener, a loss to the Vikings in Minnesota, Brian played sparingly. A week later, the team was routed 41-0 in Tampa by the Buccaneers. With the season already on the brink of disaster, the Bears coaching staff made a desperate move. Middle linebacker Barry Minter had been slowed by an injury, so they subbed Brian for him. The rookie was sensational. In his first start, he registered 13 tackles and had a sack against the New York Giants. Chicago lost again, however, and then dropped its fourth straight a week later to the Detroit Lions.

Winless heading into October, the season was all but over for the Bears. This, of course, made Brian an even bigger star in Chicago. It had been some time since the fans seen anyone play with his passion and fearlessness. And not only did Brian give the fans something to cheer about, he also provided Jauron something to build around. Against the New Orleans Saints, he recorded 15 tackles. In a rematch with the Vikings the following Sunday, he suffered a painful separation of rib cartilage, but still managed the first multi-sack game of his career.

In a November tilt with the Buffalo Bills, Brian racked up16 tackles. A week later, he helped the Bears exact some revenge against the Bucs, intercepting a pass in the fourth quarter to key a 13-10 victory. The win was just the third on the year for Chicago, which wound up at 5-11.

For Brian, the year was reminiscent of what he had gone through in college. He was the budding star on a lackluster squad, leading the team in total tackles (165), sacks (8) and solo tackles (103). Tabbed as a second team All-Pro by The Football News, he became just the third Bear in franchise history to be named NFL Defensive Rookie of the Year. Voted as a first alternate to the Pro Bowl, he flew to Hawaii for the game after an injury sidelined Detroit's Stephen Boyd.

Not surprisingly, Chicago’s blue-collar fans loved Brian’s hard-hitting style. They also applauded his low-key attitude. Brian never talked trash or showed up an opponent, and he was unwavering in his loyalty to his family, friends and teammates. Comparisons to former Chicago greats Bill George, Dick Butkus and Mike Singletary were inevitable. Brian appreciated the praise, but said it might be a bit premature.

Brian hoped for more support from his teammates in 2001, but the outlook wasn’t particularly sunny for the Bears. The preseason quarterback battle between Miller and Shane Matthews did not exactly get fans' adrenaline pumping, while unheralded James Allen was the top returning running back. The most promising part of Jauron’s offense was the line, where tackles James “Big Cat” Williams and Blake Brockermeyer anchored a solid unit. The coach also hoped for big things from receiver David Terrell, the team’s first-round choice out of Michigan.

On defense, Chicago again went free-agent shopping, signing mammoth tackles Ted Washington and Keith Traylor. Jauron's plan was to create more space for Brian to roam the field—a scheme similar to the one Rocky Long had employed with the Lobos. Behind Brian in the secondary, Brown captained an improving group that included Walt Harris and Thomas Smith on the corners.

To the utter amazement of virtually every rational football fan, the Bears enjoyed a great season, going 13-3 to win the NFC North. Though the team lost in the playoffs to the Philadelphia Eagles, Chicago provided the hometown fans with thrills no one anticipated, including several improbable last-second victories. Miller’s steadying influence at quarterback propelled the offense, and receiver Marty Booker hauled in 100 passes and scored eight touchdowns. The contributions of newcomer Anthony Thomas at tailback were even more important, as he supplied Chicago with its first real rushing threat in years. In fact, the first-year Michigan productwalked away with honors as Offensive Rookie of the Year.

The defense, meanwhile, matured into a dangerous and opportunistic group that made opponents pay dearly for their mistakes. With Washington and Traylor clogging up the middle, Chicago finished second in the NFL against the run, forcing enemy signal callers to drop back time and again in obvious passing situations. The results were pleasingly predictable for the Bears, who racked up 48 sacks and allowed the fewest points (203) in the league.

Brian, of course, was Chicago’s most fearsome defender. After the Bears dropped their opener to the Ravens in Baltimore, he rallied the team with a series of inspiring performances. In a 31-3 win in Atlanta over the Falcons, he dominated from sideline to sideline. Going into the the game, the contest was billed as a showdown between the NFL’s two hottest young stars: Brian and Michael Vick. The Atlanta quarterback never had a chance. Brian made eight tackles, picked off a pass, sacked Vick once and returned a fumble 90 yards for a touchdown. The effort, which earned him honors as NFC Defensive Player of the Week, turned heads leaguewide.

Just as impressive was the way Brian picked up his play down the stretch. Four times in December he paced the Bears with double-digits in tackles. Against the Packers in Green Bay, he buried Brett Favre for his fifth sack of the year, then intercepted a pass and took it 41 yards the other way for a TD. Two weeks later Brian flashed his receiving skills, catching a 27-yard scoring toss from holder Brad Maynard on a fake field goal. In Chicago’s 33-13 playoff loss to Philly, he topped the team with 11 tackles, including nine solos.

For the year, Brian’s 148 tackles led the Bears, and he added three interceptions and six sacks. Selected as a first team All-Pro by every major football publication, he was honored as NFL Defensive Player of the Year by Football Digest and placed fifth in the balloting for league MVP, highest of any defensive player. Brian was also the NFC’s top vote-getter for middle linebackers for the Pro Bowl.

The double-edged sword of the Bears’ fine 2001 campaign was that they played to unrealistic expectations in 2002. The team, which had clearly overachieved, simply couldn’t match the results of the previous year. Injuries ravaged both the offense and defense, as Chicago suffered through an eight-game losing streak from September to November. The team limped home at 4-12. Miller struggled at quarterback and was eventually replaced by Chris Chandler, Thomas’s production dropped off significantly, and the offensive line didn’t stay healthy. The unit’s most consistent player was kicker Paul Edinger, who scored 95 points.

On defense, the Bears were good, but didn’t create as many turnovers as the team needed. Brian led the club in tackles in more than half of Chicago’s games, including 17 stops against the Vikings on the first weekend of the season. He was also sensational under the bright lights of Monday Night Football, terrorizing the St. Louis Rams and Miami Dolphins in a pair of showcase matchups. Overall, Brian finished with 214 tackles, surpassing Butkus’s single-season franchise mark, and went to the Pro Bowl for the third year in a row. More often than not, however, his stellar work was undermined by his Chicago teammates.

Despite the team’s struggles, the Bears understood Brian's value to the team and locked him up with a new nine-year contract. Reports said the package was worth more than $56 million.

Other deals cut by the Bears heading into the 2003 season included a pair of free-agent signings, quarterback Kordell Stewart and tight end Desmond Clark. The draft also produced some welcome additions, including Penn State’s Michael Haynes. But perhaps most interesting was the selection of Rex Grossman, who was quickly tabbed as Chicago’s quarterback of the future.

The future arrived sooner than expected. Stewart was spotty in his starting opportunities, and Chris Chandler didn’t play much better. The Bears lost five of their first six, which put Jauron on the hot seat. He turned to Grossman for the campaign’s last three contests, and the rookie gave Chicago fans a glimmer of hope for the years to come. But even though the team rebounded from it’s slow start to go 7-9, Jauron’s fate was sealed. The coach was canned after a rocky five-year tenure at the helm.

For Brian, the firing of Jauron signalled the beginning of the next chapter in his career. He enjoyed another terrific season, registering 115 tackles and returning to the Pro Bowl. Brian, however, wasn’t quite as active as in years past. For the first time in his career, he didn’t register a forced fumble or interception.

That fact aside, Brian was still the centerpiece of Chicago’s championship picture. Surrounding him with the talent necessary to contend was another matter. The Bears’ first step in that direction was naming Lovie Smith as the team’s new head coach. Formerly the defensive coordinator in St. Louis, Smith was known as someone who players liked and respected immensely. His choices of Ron Rivera and Terry Shea to run the defense and offense, respectively, were applauded by fans and the media.

With a relatively young roster, expectations for the 2004 Bears were modest. The club added running back Thomas Jones as a free agent, while Grossman prepared for his first season as the starting quarterback. On defense, Brian led a group stocked with first-round draft draft choices. The front four was particuarly quick and athletic, which would give Smith and Rivera loads of blitzing and coverage options.

Unfortunately, the injury bug bit the Bears early and often. The first victim was defensive playmaker Brown, who went down for the season after tearing his achilles tendon in a September victory over the Packers . Brian sat out the next two games with a sore hamstring—the first time in his pro career he watched from the sidelines. Chicago got more bad news a week later when Grossman was lost for the year after hurting his knee against the Vikings.

Without their QB, the Bears, already thin on offense, sunk to bottom of nearly every one of the league's statistical categories. Smith turned to the defense to spark his troops. Brian did his part in his return, racking up 12 tackles and a sack against Washington, but the punchless Bears lost 13-10. At 1-5, Chicago was a step away from disaster. But the club reversed its fortunes with a three-game winning streak, including gutty victories on the road in New York and Tennessee.

Bouyed by his team's good play, Brian was on his way to another Pro Bowl when his nagging leg injuries caught up to him. He didn't suit up for five of Chicago's last seven games. The Bears won only once during the stretch, and finished at 5-11.

As the 2005 season began, the Bears recognized what it would take to become a championship contender. The defense would have to continue its progress—hardly a major worry with Smith and Rivera calling the shots, plus Brian was healthy again. The offense would need more balance, meaning Grossman needed to evolve into a dependable passer and the receiving corps had to step up as well.

The popular wisdom among NFL pundits was that this would take a couple of years. It took one. After a slow start in ’05, the Bears roared into first place with eight straight victories and won 10 of their final 12—despite losing Grossman to injury for much of the campaign. Jones, Bryan Johnson, and Cedric Benson handled running duties, while Muhsin Muhammad gave the team the go-to receiver it needed. With Kyle Orton taking most of the snaps, however, Chicago’s aerial attack was totally impotent.

The key to Chicago's turnaround was the defense. In the team’s run to the playoffs, Brian was a one-man gang. During one stretch, he registered 10 or more solo tackles in six straight games.

After the D found its rhythm, Brian refused to allow the unit let up. If anyone made a mental mistake or gave less than his full effort, he wasn't afraid to point it out. Criticism by teammates earlier in Brian's career that he was too nice in the defensive huddle was forgotten. By the end of 2005, in fact, most thought he was a jerk. With the Bears allowing the fewest points in the NFL, Brian was an easy choice for Defensive Player of the Year.

Chicago’s linebacking corps also got great production out of Lance Briggs. Pass rushers Adewale Ogunleye, signed as a free agent from the Miami Dolphins, and Alex Brown tortured enemy quarterbacks, and Tommie Harris and Tank Johnson took important steps toward stardom. The defensive backfield was anchored by corner Nathan Vasher.

The Bears chugged into the playoffs for the first time in four seasons with high hopes, but lost to the Super Bowl-bound Carolina Panthers, 29–21. Chicago played catch-up all day, and still had a chance late in the fourth quarter, when they lost the ball on a controversial interception call.

With Grossman healthy for 2006 and every starter returning, the Bears were considered among the favorites in a weak NFC. They held up their end of the deal, thanks in part to an offense that could be potent at times. Again, however, it was the defense that set the tone in Chicago. Indeed, the Bears established themselves as the hardest-hitting unit in football.

The team won its first seven games, then cruised to victory in six of its final nine for a 13–3 record. The Bears began the season with a 26–0 win over the Packers in Lambeau Field, and later blanked the Jets for their second shutout. Brian made a dramatic end zone interception to seal the deal against NewYork..

Brian also had a big day in a Monday Night Football matchup with the Cardinals in Arizona. He refused to let the defense quit after Chicago fell behind by 20 points. In one of the season's more unlikely comebacks, the Bears clawed their way back to win 24–23. Brian had 18 tackles and stripped Edgerrin James of the football on a game-turning play.

As the season progressed, Chicago also proved it had the league's best special teams—thanks mostly to Devin Hester. A second-round pick out of Miami, he returned punts, kicks, and missed field goals for a total of six touchdowns. Hester was part of a controversial draft class engineered by Smith, who dealt away the team’s top pick and selected six defensive players in the first six rounds. No one could argue with the coach's results, however. At season’s end, Brian was one of eight Bears to earn Pro Bowl recognition. The others were Harris, Briggs, Hester, Olin Kreutz, Robbie Gould and Brendon Ayanbadejo.

The Bears were tested immediately in the playoffs by the Seattle Seahawks, who were coming off a miracle win over the Dallas Cowboys in the opening round. Chicago held a 21–14 lead at halftime, but the Seahawks put 10 points on the board to start the second half. The Bears knotted the score on a field goal by Robbie Gould, then won in overtime on a 49-yarder by their star kicker. Grossman, who gave the team a huge boost with his solid paly, connected on a long pass with Rashied Davis to set up the winner.

The defense took center stage a week later, when the New Orleans Saints came to town for the NFC Championship. The Bears converted three early turnovers into three field goals, then scored on a long drive to take a 16–0 lead. The Saints closed the gap to 16–14, but the Bears turned up the defensive pressure in the second half. Drew Brees was forced to ground the ball in his own end zone, which resulted in a safety. Later, Ogunleye and Vasher created key turnovers, and Chicago pulled away for a convincing 39–14 win—and the franchise's first trip to the Super Bowl in 22 years.

Prohibitive underdogs against the Indianapolis Colts, the Bears entered Super Bowl XLI with a chip on their shoulder. Hester made an immediate statement when he returned the opening kickoff 92 yards for a touchdown. After Peyton Manning responded with a TD strike to Reggie Wayne, Grossman fired a four-yard scoring strike to Muhammad to put Chicago ahead 14-6. The game turned ugly for the Bears from there. The Bears committed one turnover after another, including an awful throw in the fourth quarter by Grossman that floated into the arms of Kelvin Hayden, who took it back 57 yards to salt the game away.

In a contest billed by some as a showdown between Brian and Manning, the Colts won 29-17. Neither star enjoyed his best day of the year. Brian made seven solo tackles and assisted on three others, but Indy's ball-control offense wore down him and his teammates. Manning, meanwhile, settled down after an early INT and was the default choice as MVP.

Speaking of MVP quarterbacks, that's now the pivotal question in Chicago. Can the Bears win it all with Grossman? Unfortunately for Rex, most would say no.

The one certainty: Brian is the heart and soul of the Bears regardless of who’s calling the plays or taking the snaps. He is a winner both on and off the field, his jersey is among the top sellers leaguewide, and his popularity with fans in Chicago has been essential to the team in its new home, the refurbished Soldier Field. Given the comparisons to the Hall of Famers who roamed the middle for Chicago in years past, the question is whether his legacy will be that of Dick Butkus—a ferocious player who toiled his entire career on losing teams—or Mike Singletary, who went to the playoffs year after year, and also won a Super Bowl.

BRIAN THE PLAYER

Brian’s athletic prowess is undeniable. At 6-4 and more than 250 pounds, he is the ideal size for today’s middle linebacker. Agility and indefatigable pursuit are two of his greatest assets. Brian also has the power to shed offensive lineman and the speed to track down ball carriers.

When Brian entered the league, the game moved faster than he could think. His move to middle linebacker proved a perfect fit. In Chicago’s scheme, he is allowed to use his instincts to read plays and make tackles. Like any NFL defender would, Brian benefits from a system that simplifies his responsibilities.

No one in the NFL is a better tackler than Brian. Teammates and opponents often comment that the sound of pads against pads is different when he does the hitting. The thud resonates across the field. You can almost feel the pain he inflicts on opponents.

The funny thing is, Brian’s a decent guy. In fact, he has been criticized by no less an expert than Dick Butkus for not being mean enough. The Hall of Famer elevated intimidation to an art form during the 1960s, and is suspicious of Brian’s admitted “soft side.” God only knows what he’d say if he knew Brian’s favorite musical groups are N*Sync and Backstreet Boys.

That Brian refuses to view football as a life-and-death struggle does not mean he lacks intensity. On the contrary, he is an extremely hard worker who commands respect from this teammates by the example he sets in practice and games. Anyone who agrees with Butkus’s viewpoint should ask opposing quarterbacks, running backs and receivers if Brian is tough enough.

EXTRA

# No one is surprised that Brian grew to be so big. He weighed over 12 pounds when he was born, and when he broke a wrist in high school, doctors told him that his growth plates showed he might get as tall as 6-7.

# Brian was named all-district in basketball his senior year at Lovington High School.

# At New Mexico, Brian majored in Criminology. He had a 23-pound cat named Norman.

# Brian finished his career as New Mexico’s third all-time leading tackler with 442 stops. He also had three interceptions, 11 sacks and caused 11 fumbles.

# One of Brian’s biggest thrills prior to starting his pro career was meeting Bill Parcells. During a pre-draft meeting with the Jets, he was watching film with linebacker coach Bob Sutton, and the legendary coach popped into the room and shook his hand.

# After being named NFL Defensive Rookie of the Year in 2000, Brian bought Rolex watches for Chicago’s starting defensive line. He joined Mark Carrier (1990) and Wally Chambers (1973) as the only Bears to win the award.

# In 2002, Brian became the seventh Chicago Bear to go to the Pro Bowl in each of his first three seasons. Dick Butkus and Gale Sayers were the last two to do it (1965 to 1967).

# Brian’s jersey was the NFL top seller in 2002, followed by Tom Brady's and Michael Vick's.

# In 2005, Brian became the fifth player in history to win Defensive Rookie of the Year and Defensive Player of the Year during his career.

# Brian registered an NFC-best 141 tackles in 2006.

# Brian led the Bears in tackles in six of his first seven NFL seasons.

# Brian has become a big Cubs fan. His biggest baseball thrill was singing "Take Me Out to the Ballgame" at Wrigley Field.

# Brian isn’t the only New Mexico alum in the NFL. The others are: Jarrod Baxter ('01) - Houston Texans, Joe Maese ('00) - Baltimore Ravens, Terance Mathis ('89) - Pittsburgh Steelers, Scott McGarrahan ('97) - Miami Dolphins, and David Sloan ('95) - New Orleans Saints.

# Brian’s teammates call him “Grrr-Lacker” or “Lak.”

# Brian is the official spokesperson and cover athlete for "SEGA Sports NFL 2K3."

# Brian is an active supporter of the Special Olympics in the Chicagoland area and New Mexico.

# Brian’s younger brother, Casey, played middle linebacker for Lake Forest College, a Division III school in Chicago. After graduating, he got a tryout with the Bears. Casey now plays in the Arena Football League.

# Brian owns an auto dealership in Lovington, New Mexico.

# Brian has playful nicknames for Casey (“Son”) and his stepfather (“Dork”).

# Brian’s mother and stepfather are now divorced, but remain on good terms. Brian thinks so much of Troy Lenard that he bought him a 100-acre ranch in Texas.

# Brian has one daughter, Pamela. He and his former wife, Lauren, divorced in 2003. She and Pamela now live in Phoenix.

# Brian briefly dated Paris Hilton in the fall of 2003.

# Early in 2004, Brian tried his hand at professional wrestling, taking the ring under the name, the "Worm." When the Bears caught wind of his off-season hobby, they quickly put an end to it.