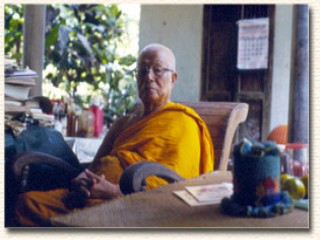

Buddhadāsa Bhikkhu biography

Date of birth : 1906-05-21

Date of death : 1993-05-25

Birthplace : Phumriang, Thailand

Nationality : Thai

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2011-01-23

Credited as : Famous ascetic, Buddhism, founder of Wat Suan Mokkhabalārama

Buddhadāsa Bhikkhu , the founder of Wat Suan Mokkhabalārama, outside of Chaiya, Surat Thani Province, southern Thailand, established himself as the most creative and controversial interpreter of Theravāda Buddhism in the modern period.

Born on May 21, 1906, as Nguam Phanich, Buddhadāsa Bhikkhu completed his lower secondary education in Chaiya and went to work at age 15 in his family's business after his father's untimely death. Ordained a Buddhist monk in 1927 at Wat Ubon, he rapidly gained a reputation for his intellectual prowess, interest in meditation, and ability as a preacher. Taking the name Buddhadāsa, Servant of the Buddha, he furthered his studies in Bangkok at Wat Pathum Khongkha, where he distinguished himself in Pāli and Buddhist studies. Returning to Chaiya to lead a more contemplative life, he settled down at a deserted monastery (Thai: wat; Pali: vasa) outside of town. After ten years, as farmers gradually took over the land around the temple, Buddhadāsa established his meditation and study center in a 150 acre plot of virgin jungle about five kilometers outside of town.

The new center of Suan Mokkhabalārama, or Suan Mokh as it was more generally known, combined aspects of early Buddhist monastic life with modern methods of propagating the Dhamma (the Buddha's teachings). The 50 to 60 monks residing at Suan Mokh at any given time lived in simple wooden structures with few of the amenities characteristic of monks who lived in large urban monasteries. While they observed the traditional precepts of the monastic life, most monks at Suan Mokh spent more time in meditation and study than the typical Thai monk. Moreover, many engaged in appropriate forms of manual labor such as casting bas-reliefs copied from such ancient Indian Buddhist sites as Sañchi and Barhut. These were then shipped to monasteries around the country.

While the setting of Suan Mokh and the life style of the monks residing there seemed close to the ideal associated with the Buddha and his disciples, other structures were quite modern. For example, there was a "Spiritual Theater" equipped to teach the Dhamma with modern audiovisual equipment. The walls were covered with mural paintings not only from the Theravāda Buddhist tradition of Thailand, but also from the Zen Buddhism of China and Japan and from other religious traditions including Christianity. The paintings taught the basic Buddhist precepts, in particular the importance of non-attachment, an attitude which frees one from egoistic preoccupations and the greed and hatred stemming from them.

Buddhadāsa's teachings from the 1950s on were collected and published in nearly 50 substantial volumes. They include his written work, as well as numerous talks and lectures which were recorded and transcribed. The oral nature of Buddhadāsa's thoughts tends to give the material an informal and contextual cast. Very little has been translated into English or other foreign languages, which accounts for the fact that he was not as well known as Buddhist interpreters who write in English. Part of Buddhadāsa's unique genius, however, stemmed from the fact that, with the exception of a pilgrimage to Buddhist sites in India, he lived exclusively in Thailand. He read widely, particularly in the Zen Buddhist tradition which he admired, and had rather extensive contacts with Americans and Europeans, several of whom were monks in residence at Suan Mokh. Many of the Thai monks associated with Suan Mokh were, furthermore, well educated, helping to make Buddhadāsa's monastery an outstanding place for Buddhist practice and study.

Buddhadāsa was controversial for several reasons. In the first place he was quite critical of conventional Thai Buddhism, which he saw as dominated by a desire to use religion for one's own personal, worldly benefit. In the Thai Buddhist context this is called "making merit" (Thai: tham puñña). Buddhadāsa found the preoccupation with the externals of religious rituals and ceremonials with the intent of bettering one's self in the world to be a kind of materialism rather than true religious practice. Buddhadāsa was equally critical of a kind of mindless philosophizing which has no transformative effect on one's attitudes and actions. Specifically, he thought that the memorization of endless categories of Abhidhamma philosophy was not only useless, but led one away from genuine religious practice and understanding.

However, Buddhadāsa was more than a critic of Thai Buddhism. His system of thought represented one of the most comprehensive interpretations of Theravāda Buddhism of the modern period, or, as some admirers claimed, ever since Buddhagosha standardized Theravāda doctrine in the 5th century A.D. It was an influence comparable to St.Thomas Aquinas in Roman Catholicism. The originality of his thought stemmed from a profound understanding of such seminal Buddhist concepts as interdependent co-arising (paticca samuppāda), impermanence (aniccā), not-self (anattā), and, of course, Nirvāna. His thought was characterized by the use of language in a way which provoked deep insight into these ideas. For example, he made the ordinary Thai term for "nature" (dhamma-jāti) into a means of understanding the difficult but fundamental concept of Theravāda Buddhism, interdependent co-arising (paticca samuppāda).

While Buddhadāsa should be seen as a reinterpreter of his own Theravāda tradition, he also studied and was influenced by other religions. At the deepest level, Buddhadāsa saw all religions standing for something quite similar. For example, he argued that terms like God, Tao, and Dharma all point to the same underlying truth which transcends all the ordinary distinctions on which conventional language is built. Hence, the religious journey or path should be toward an understanding of things the way they really are, a universal state of being in which we are able to realize our essential oneness with human beings of all kinds and persuasions as well as with the universe. This is a kind of religious socialism in which our own personal well-being is realized in terms of the good of the whole. It is an ideal, to be sure, but one which Buddhadāsa hoped would inspire people to work for the peace and harmony of the entire human community.

Buddhadāsa Bhikkhu suffered from heart attacks and strokes as he grew older, but his ardent desire to teach helped to keep him alive. He finally succumbed to a stroke just before his birthday celebration in 1993. Shortly before he died, he enhanced the Suan Mokkh center by establishing the International Dhamma Hermitage to foster principles of Buddhism among visitors to Thailand. The Hermitage provides instructional curricula for foreign students and meeting facilities for religious leaders from all nations. A final project which he conceived, and which was undertaken by his followers after his death, was the establishment of the small Dawn Kiam monastery (Suan Atammayatärämä). Dawn Kiam is a missionary training facility for monks from other lands.

Unfortunately, at the present time only a small portion of the extensive writings by Buddhadāsa have been translated from Thai into English. The most extensive collection has been translated under the title Toward the Truth, translated and edited by Donald K. Swearer (1971). Some of his shorter essays have been translated and published in English in Thailand but are not generally available in the West—e.g., Christianity and Buddhism, translated by B. Siamwala and Hajji Prayoon Vadanyakul (Bangkok, 1967). A major portion of Buddhadāsa's lectures on Christianity and Buddhism has been reprinted as a chapter in Donald K. Swearer, Dialogue. The Key to Understanding Other Religions (1980). Buddhadāsa has figured into some scholarly work on Theravāda Buddhism—e.g., Donald K. Swearer, "Bhikkhu Buddhadāsa on Ethics and Society," in Journal of Religious Ethics (July 1, 1979)—and has been the subject of several doctoral dissertations in German, French, and English—e.g., Patarporn Sirikanchana, The Concept of Dhamma in the Writings of Vajirañāna and Buddhadāsa (1985).