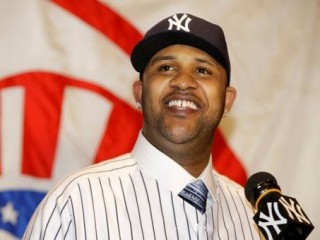

C.C. Sabathia biography

Date of birth : 1980-07-21

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Vallejo, California

Nationality : American

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2010-11-10

Credited as : Baseball player MLB, pitcher with the New York Yankees,

0 votes so far

All of the men on both sides of the Sabathia family were big, so there was little question that C.C. would one day tower over his classmates. As a child, however, he was not particularly large for his age. He was a talented athlete nontheless and regularly competed in baseball, basketball and football against older boys.

C.C. took to the diamond around the age of four. He had an instant passion for the game which never diminished. The kids C.C. gew up with in the neighborhood played on the same teams with him right into high school. They formed a bond that still exists today.

C.C.'s father left the family in 1992, leaving Margie as a single parent. She took a keen interest in her son's baseball career. Margie was so set on C.C. becoming a pitcher that she invested in catching gear for herself.

Margie also carefully monitored her son's Little League games. C.C. would cruise along until someone tagged him, and then he would lose his cool. Sometimes he would tug his cap down and overthrow, and sometimes he would start to cry. His mother pulled him off the mound a couple of times and let him think about his actions on the long, quiet car rides home. The next day they would talk it out. Eventually, the California cool Margie helped C.C. develop off the field became his trademark on it.

A big sports fan in a thriving community just outside of Oakland, C.C. rooted for the Giants and A’s and attended many games at both ballparks. His favorite players were Will Clark, Robby Thompson, Matt Williams, Jose Canseco, Mark McGwire, Dave Stewart, Dave Parker and Carney Lansford. When Barry Bonds came to town, C.C. embraced the slugger as his new hero, along with young Ken Griffey Jr.

By the time C.C. entered Vallejo High School in 1994, he was a menace to his mother. He had begun to grow in eighth grade and stood 6-3 as a freshman. He was throwing so hard and had grown so tall—he also had the beginnings of a beard—that California scouts started hearing stories about a man-child breaking 90 mph on the outskirts of wine country.

The coaches at Vallejo couldn’t wait to get their hands on C.C. Vic Wallace, who ran the basketball team, turned him into one of the county’s best power forwards. C.C.led the Apaches to within a victory of the state championship.

As a senior, C.C. had a great season for the Vallejo football squad, which made the state semifinals. He made All-Conference as a tight end and was heavily recruited by UCLA and the University of Hawaii. He signed a letter of intent with the Warriors, with the understanding that he might opt for a diamond career. He also starred in basketball that winter.

ON THE RISE

In the spring of 1998, C.C. came into his own as a pitcher. Baseball America listed him as Northern California's top prep prospect. He was a perfect 6–0 in his last season, with a 0.77 ERA and 82 strikeouts. Despite these numbers, C.C. still thought of himself as a hitter. He batted in the heart of the lineup and was the team’s best slugger. When he wasn’t pitching, he either played left field or first base.

C.C. was selected with the 20th pick in the '98 draft by Cleveland. The Tribe had come within a couple of outs of winning the World Series the previous autumn. After some contract wrangling, C.C. joined Burlington of the Appalachian League in time to make five starts, whiffing 35 batters in 18 innings. He was a little disappointed, however, that the Indians didn't want to use him as a hitter.

A sore elbow delayed the start of C.C.’s 1999 season, but once healthy, he climbed from low-A Mahoning Valley up through Columbus to Kinston of the Carolina League. He was a combined 5–3 in 16 starts, with a 3.29 ERA and notched a strikeout an inning at each stop. Opponents managed just a .198 average against him.

C.C. spent the first half of 2000 with Kinston before moving up to Class-AA Akron. He had another solid season, pitching in the Futures Games in Atlanta and starting for the Indians in the Hall of Fame Game against the Arizona Diamondbacks. He was rated Cleveland’s #1 prospect and the #2 prospect overall in the Eastern League.

These rankings proved prohetic, as C.C. exploded on the big-league scene the following season. At the age of 20, he became the Tribe’s most valuable starter, going 17–5 with 171 strikeouts. He joined Bartolo Colon and Dave Burba to give Cleveland a staff that was strong enough to take the club to the top of the Central Division.

In the ALDS, C.C. started Game 3 against Seattle after the teams had split the first two games. After walking in a run in the first inning, he took a deep breath and proceeded to blow the Mariners away. C.C. was dominant the rest of the way, and the Tribe hitters torched the M’s in a 17–2 victory. Unfortunately, the Indians scored just three more runs in the series and bowed out in five games. As soon as the series ended, GM Mark Shapiro locked C.C. up with a five-year deal.

After his stunning rookie campaign, C.C. faced overwhelming expectations in 2002. It wasn't until late in the summer that he relaxed and began to meet them. With the exception of a near no-no in April, C.C. got pounded early in the year. He rediscovered the magic in his final 11 starts, winning seven times with an ERA below 3.00. His final numbers were still a little ugly—88 walks and a 4.37 ERA—but he won 13 times and fanned 149 batters in 210 innings. The Indians, who could not produce the offense they had the year before, sank to 74 wins.

C.C. continued his solid pitching into the 2003 season. He went five innings or more in all but one of his 30 starts and managed to notch 13 wins against only 9 losses despite poor run support. His 141 strikeouts and 3.60 ERA ranked among the league’s best.

MAKING HIS MARK

That winter, C.C.—whose weight was now in the high 200s—started thinking more seriously about his body. He hired a dietician to guide him and began working with a strength coach. He also foudn a personal chef. The biggest change was drinking two dozen cups of water each day. He dropped 15 pounds.

By 2004, the Indians had retooled themselves around a group of young hitters including Travis Hafner, Victor Martinez, Grady Sizemore and Casey Blake. They won 89 games but fell short of a Wild Card berth. C.C. had a so-so season. After riding a 5–4 first-half record to an All-Star berth, he never really picked it up in August and September. He finished 11–10 with a 4.12 ERA. Fortunately, Cliff Lee and Jake Westbrook blossomed, giving the Tribe two more reliable starters.

Though still young, C.C. was now in his pitching prime. This was actually a matter of concern for some in the Cleveland organization. They were growing tired of watching C.C. string together a few great starts only to melt down on the mound after a fielding error, a bad call by an umpire, or a home run off a good pitch. It was time for him to grow up.

In 2005, C.C. reached the level of maturity the Cleveland hoped to see, and the Indians had another encouraging year. The team won 93 times and just missing the Wild Card after a great September run. C.C. went 15–10 and led the Tribe with 161 strikeouts. Though he struggled in June and July, he recovered for the stretch run and untouchable in August and September. At one point, he recorded W's in sevenstraight starts. The Indians exercised C.C.'s 2006 options after the season, then inked him to an extension that would keep him in a Cleveland uniform through 2008.

Eager for their team to take the next step, Cleveland fans were disappointed in the Indians in 2006. The club played inconsistently, sank below .500, and finished far out of the playoff race.

C.C., by contrast, had a solid season, going 12–11 despite shoddy run support. He fanned 172 batters in just 28 starts and turned in a sparkling 3.22 ERA. He also led the league with sixcomplete games. C.C. pitched the entire year banged up. First, he strained an oblique on Opening Day, and then he developed pain in his right knee, which he got scoped after the season.

C.C. admitted after '06 campaign that the Cleveland pitchers may have lost their edge with so many experts picking them to dominate. When they started slow and the Detroit Tigers broke from the gate fast, the Central crown was out of reach by June and the season was lost.

When C.C. took the mound in 2007, he looked more confident—and pitched that way. He won with and without his best stuff and shrugged off the little disasters that befall every major leaguer. He also learned not to read his own newspaper clippings.

Focused completely on his job, C.C. cruised to victories in his first five starts. After a hiccup against the A's, he strung together four more wins. His control was impeccable, and no one could touch him with two strikes. C.C. was a horse, leading the league in starts and innings pitched and finishing the year with a 19–7 record, 3.21 ERA and 209 strikeouts.

The Indians took the AL Central with 96 victories as Grady Sizemore, Victor Martinez and Travis Hafner had huge years at the plate. C.C. was backed in the Cleveland rotation by Fausto Carmona and Paul Byrd, who combined for 34 wins. Closer Joe Borowski notched 45 saves despite some ugly numbers.

The postseason began on a positive note for C.C. and the Tribe, as he beat the Yankees in Game 1 of the AL Division Series, 12–3. However, he was not sharp, allowing a leadoff homer to Johnny Damon and laboring to throw strikes. He barely made it through the requisite five innings to qualify for the win. C.C. threw 114 pitches and walked six.

Even without their ace athis best, the Indians they wrapped up the series in four games. That gave C.C. had plenty of rest before Cleveland faced Boston in the ALCS. C.C and Josh Beckett hooking up in Game 1. The Tribe drew first blood on a Travis Hafner home run, but the Red Sox answered with a single run in the first and pushed four more runs across in the bottom of the third. By the fifth, C.C was out of gas and out of the game, having yielded eight runs.

Cleveland rebounded from the blowout and captured the next three. C.C. took the mound in Game 4 with a chance to close out the series. This time he and Beckett engaged in a classic pitcher’s duel, taking the contest into the seventh with Boston holding a slim 2–1 lead. But once again, the Red Sox got to C.C. and cruised to a 7–1 victory. Boston took the next two to deny Cleveland its first trip to the Fall Classic since 1995.

It was painful to watch the Red Sox move on and defeat the Colorado Rockies in the World Series. In fact, for the first time he could remember, C.C. avoided the Fall Classic altogether. The sting was lessened somewhat when he was named the AL Cy Young Award winner. C.C. became just the second Indian to win the award, following Gaylord Perry. Interestingly, Cliff Lee—a non-factor in 2007—would return in 2008 with a big season and become the third Indian to earn this honor.

With C.C. and Lee leading the rotation in ’08, plus tons of young talent on the roster, Cleveland fans had every reason to believe their team would rule the Central for years to come. But it didn't work out that way. During a long, disappointing season, the Indians seemed unable to get out of their own way. They finished a lackluster 81–81, a distant third in the division. C.C., in the walk year of his contract, wasn’t around for the finish. He won just six of 14 decisions before the Indians decided to rebuild. They traded him on July 7 to the Milwaukee Brewers for a passel of prospects highlighted by Matt LaPorta. After the trade, C.C. took out an ad in the Cleveland Plain Dealer thanking the fans for their love and support.

The change of scenery did C.C. a world of good. He rediscovered the bite on his slider and pitched three complete games in his first four starts for the Brewers—tonic for a team whose pitchers rarely went nine. Over the next three months, he posted an 11–2 mark and practically pitched Milwaukee into the playoffs by himself. C.C. finished with a 17–10 record, 2.70 ERA and a career-best 251 strikeouts, which trailed only Tim Lincecum for the major league lead.

C.C.’s best game came against the Pirates in August. Pittsburgh’s only hit was a check swing dribbler that C.C. bobbled when he attempted a bare-handed pickup. The play was ruled a hit, denying him a no-hitter. His most important victory came on the final day of the season, when he handcuffed the Chicago Cubs while the New York Mets lost to the FLorida Marlins—boosting the Brewers into the postseason for the first time since the 1980s.

Once again, C.C.'s season ended on a down note, as he yielded a grand slam to light-hitting Shane Victorino in Game 2 of the NLDS in Philadelphia. He was chased by the Phillies in the fourth inning.

A few weeks later, C.C. found himself on the business end of a huge deal with the Yankees. The team wanted him in the worst way and was willing to pay the price—in this case, $161 million over seven years. The team also brought in A.J. Burnett and Mark Teixeira to beef up a roster that had failed to make the playoffs for the first time since the mid-1990s.

Manager Joe Girardi tabbed C.C. as the Opening Day starter, and he responded with an inferior outing against the Orioles. A month later. he gained a measure of revenge, tossing a four-hit shutout against Baltimore. Still, some fans questioned C.C. He was expected to be the anchor of the New York rotation. During the season’s first half, he was good but hardly great.

C.C. found his groove as the summer heated up. He ended up winning 19 games, becoming the ace that the Yankees so desperately needed. Just as valuable a contribution was his friendly, relaxed attitude in the clubhouse. Along with Burnett and newcomer Nick Swisher, he loosened things up during a year when the pressure was on the team to make it back to the postseason.

The Yankees did more than that, of course. C.C. won the opening game of the Division Series against the Minnesota Twins, and New York went on to sweep all three games. Next C.C. notched a pair of victories against the Angels in the ALCS, winning the series MVP award for good measure. He struck out seven in eight innings and allowed just one run in Game 1, a 4–1 victory. He returned to the mound in Game 4and threw a gem on three days rest, as the Yanks won 10–1. They closed out the Angels in six games.

C.C. started Game 1 against the Phillies in the World Series. He didn’t have his best stuff, but still managed to go seven innings and surrender just two runs against the tough Philadelphia lineup. Both came on solo shots by Chase Utley. Lee, C.C.’s former teammate and good buddy, was the star, however, going the distance in a 6-1 win.

C.C. returned to the hill in Game 4, again on three days rest. He pitched into the seventh and left with the lead, only to see Joba Chamberlain give up a gopher ball to Pedro Feliz. The Yankees responded with three runs off Brad Lidge in the ninth for a 7-4 win and a commanding advantage in the series.

As it turned out, C.C.’s work was done. The Yankees dropped Game 5 but still returned to the Bronx with a chance to close out the Phils. They jumped on Pedro Martinez early in Game 6, building a 7-3 lead. It ended that way with Rivera on the hill. C.C. celebrated his first World Series championship like a litte kid.

C.C. may finally have figured it out. Outs are more important that strikeouts, winning ugly often gets you to the postseason. With a high-scoring offense at his disposal and a solid defense behind him, C.C. doesn't have to try to blank the oppostion to earn a W. Of course, that's often what he does, which suits the fans in New York just fine.

C.C. THE PITCHER

C.C. doesn't go out there to trick anyone. He brings heat—fastball after fastball after fastball. He has a deceptively easy motion, and the ball at times seems to explode out of his body. His arm is a lethal weapon, keeping his velocity up in the mid 90s or higher with just enough movement to prevent hitters from digging in. His sweeping curve and changeup are average, but they can be deadly working off his fastball.

C.C. is a good athlete who fields his position well. Given his size—6-7 and around 290 pounds—this is a surprise to some. But remember that he was a topflight tight end and power forward in high school.

There were always two questions about C.C., his weight and his maturity. He seems to have mastered both. Maintaining a balance between his good-natured, easy-going persona off the field and his ultra competitive streak on it is now the main challenge for C.C.