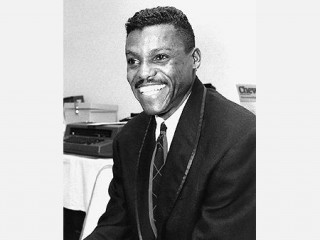

Carl Lewis biography

Date of birth : 1961-07-01

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Birmingham, Alabama, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2010-06-25

Credited as : Track and field athlete, Olympic athlete,

4 votes so far

Carl Lewis, the greatest track and field star of the 20th century, attracted intense attention to his sport in the United States in the 1980s. His early successes as a sprinter and long-jumper inspired writers to compare him to Jesse Owens, even before he equaled Owens' feat of winning four gold medals in a single Olympics. Negative publicity about his flashy style, his financial ambitions, and what many considered his arrogance made him a controversial figure. But he went on to surpass even Owens' feats by winning gold medals in three more Olympics, and questions about his personality have given way to respect for his unequaled accomplishments.

Growing up

Lewis was born in Birmingham, Alabama in 1961 to Bill and Evelyn Lewis, both teachers and gifted athletes. Evelyn was herself an accomplished track and field athlete who competed in the 80-meter hurdles at the Pan American Games while in college. Bill played football at the Tuskegee Institute, where the couple met. They worked as teachers and marched in civil-rights protests, and Martin Luther King, Jr. baptized Carl's brothers.

The Lewis family moved to New Jersey in 1963. There, Carl and his younger sister Carol picked up their parents' passion for sports. They built a homemade long-jump pit in their back yard and invited friends over for neighborhood track meets. At first, Carl didn't show much athletic talent. "I was small for my age, the runt of the family, the nonathlete," he wrote in his autobiography, Inside Track. But when he heard about Bob Beamon's world record long jump of 29 feet 21/2 inches at the Olympics in Mexico City in 1968, Lewis marked off the distance in his front yard.

As a kid, Lewis participated in track meets named for Jesse Owens, and he met Owens at two of the meets. He had a growth spurt while a sophomore in high school, and soon became a track and field standout. He put the number 25 on his jacket to show he wanted to jump 25 feet before he graduated. By his senior year, he was meeting his goal regularly. The day of his senior prom, he beat his aging sprinting idol, Steve Williams, in a race.

Several colleges tried to recruit him. In his autobiography, Lewis named the coaches and shoe companies who offered him money and gifts in violation of NCAA rules. He accepted shoes and equipment from Puma and Adidas while still in high school, and signed a six-figure contract with Nike while in college. He chose to go to college at the University of Houston in 1979, though no one there offered him money or a shoe deal, he wrote, so he could compete under well-regarded coach Tom Tellez--who became his personal coach after graduation.

The "Next Jesse Owens"

Since long-jumping was causing soreness in Lewis's knees, Tellez convinced him to change his long-jump style from a "hang" jump to a "double-hitch kick," in which the jumper pumps his arms and legs, as if running through the air. Soon he was jumping 27 feet with the double-hitch kick. In 1980, Lewis beat the world's top-rated sprinter in a 100-meter race. Writers began comparing him to Jesse Owens because he was so good at both the long jump and sprinting. He and his sister Carol both qualified for the U.S. Olympic team in 1980, although the U.S. boycotted the Olympics in Moscow to protest the Soviet Union's invasion of Afghanistan.

In summer 1980, Lewis competed on the European track circuit for the first time. He was one of several college athletes who were paid money for running abroad, in violation of NCAA rules. "Any college athlete who had been to Europe and been exposed to the opportunities for track athletes would be crazy not to think about the money," he wrote in his autobiography--whose subtitle, "My Professional Life in Amateur Track and Field," was meant to show that the "amateur" status of his sport had become a facade.

In 1981, Lewis set a world record for an indoor long jump: 27 feet, 101/4 inches, beating a previous record set by Larry Myricks, who had been favored to win the gold medal at the 1980 Olympics. The two developed a bitter rivalry. At the U.S. national championships in 1981, Lewis beat Myricks by making the second-longest jump unaided by wind of all time: 28 feet, 31/2 inches. He also won the 100-meter run. In 1982, at a meet in Indianapolis, he made a jump that some say spanned 30 feet. But in a much-disputed ruling, an official nullified the jump, claiming Lewis had stepped past the board at the end of the runway, so the jump was never measured.

That same year, Lewis joined the Lay Witnesses for Christ, a group of Christian athletes, after meeting some of its members at a meet. In 1983, a musician friend introduced Lewis to Sri Chinmoy, an Indian guru who assured Lewis that his teachings about inner peace and meditation didn't conflict with the teachings of Jesus. Lewis came to regard both Chinmoy and the Lay Witnesses as spiritual advisers.

By 1983, Lewis was the most famous athlete in track and field. At the national championships in Indianapolis, he became the first person in decades to win the 100- and 200-meter dashes and the long jump the same year. At the World Track Championships in Helsinki, he led an American sweep of the 100-meter dash, won the long jump, and led the U.S. relay team to a world-record victory.

But as the 1984 Olympics approached, Lewis was developing a reputation for arrogance. A profile in Sports Illustrated painted him as self-absorbed. Competitors thought his habit of raising his arms in victory as he reached the finish line was disrespectful to them. Some of them also resented the isolating limos and hotel suites meet promoters gave him.

The 1984 Olympics

Lewis won four gold medals in the Olympics in Los Angeles, matching Owens' performance in Berlin in 1936. He won the 100-meter race in 9.99 seconds, jumped 28 feet 1/4 inch to win the long jump, led a U.S. sweep of the 200-meter, and anchored the U.S. team that set a new world record with its win in the 4 x 100 relay.

But a backlash against Lewis's personality detracted from his feats. He was attacked as greedy when his personal manager declared that he wanted Lewis to make as much money as singer Michael Jackson. Lewis decided to stay at a friend's house, not the Olympic village, during the games, leading some to call him a prima donna. He ran his victory lap after the 100-meter race with a large U.S. flag a fan handed him. Some news reports claimed Lewis had planted the fan there to give him the flag--though he hadn't. When Lewis chose not to take all his jumps in the long-jump competition, spectators who hoped to see him break the world record booed--even though he was following good track-meet strategy, saving his strength for his other events. After the controversies, product-endorsement deals Lewis expected didn't come through, and he became bitter toward the press for a while.

After the games, Lewis took acting lessons, played a bit part in a movie, and recorded an album, The Feeling That I Feel, and some singles. The album "wasn't bad. It just wasn't good," Lewis later admitted. Still, his single "Break It Up" went gold in Sweden. He recorded with Quincy Jones and sang the national anthem at a few meets.

In 1987, Lewis's father died. He left his coveted 100-meter gold medal in his father's coffin and pledged to win another one.

Lewis and Ben Johnson

As the 1988 Olympics approached, Canadian sprinter Ben Johnson emerged as Lewis's top sprinting rival. At the 1987 World Track Championships in Rome, Johnson beat Lewis and set a new world record of 9.83 seconds in the 100-meter, while Lewis ran a 9.93. While in Rome, Johnson's coach was overheard making a comment that implied Johnson was taking steroids to enhance his performance. Word got back to Lewis. "A lot of people have come from nowhere and are running unbelievably," Lewis told a reporter. "There are gold medalists at this meet already that are on drugs," he added, but didn't reveal any names. In 1988, Lewis beat Johnson at a meet in Zurich, where he heard another allegation that Johnson was using performance-enhancing drugs.

At the Olympics in Seoul, South Korea, just before Lewis and Johnson raced in the 100-meter dash, the two shook hands. "As I looked at him," Lewis recalled in Inside Track, "I noticed that his eyes were very yellow. A sign of steroid use." Johnson took first in the race with a record-breaking 9.79 seconds, while Lewis took second with 9.92. Lewis thought he'd failed in his goal to win another gold medal in the 100-meter for his father. But before the games were over, Johnson tested positive for steroid use and was stripped of the record and the medal. Lewis was awarded the gold instead. He also won the gold for the long jump with a jump of 28 feet, 71/2 inches, and won a silver medal in the 200-meter (his friend Joe DeLoach took the gold).

Lewis continued to speak out against steroid use. He testified before a U.S. congressional committee on the subject, and he called for an independent drug-testing agency to monitor each sport. Once, speaking to a group of college students, he implied that he thought fellow U.S. Olympic athlete Florence Griffith-Joyner used steroids--but the charges were never proved, and Lewis backed down from his statement.

The 1992 and 1996 Olympics

As Lewis turned 30, other athletes challenged his dominance of track and field. Leroy Burrell, Lewis's teammate in the Santa Monica Track Club, edged him out in the 100-meter dash at the 1990 Goodwill Games and the 1991 national championships. At the World Track Championships in Tokyo in 1991, Lewis set a new world record in the 100-meter, 9.86 seconds, beating Burrell by .02 seconds. But at the same meet, long jump rival Mike Powell broke Lewis's ten-year undefeated long jump streak. Lewis surpassed 29 feet three times, including a personal best of 29 feet, 11/2 inches--but Powell broke the world record with a jump of 29 feet, 41/2 inches.

The next year, Lewis had a sinus infection during the Olympic trials, and he only qualified for the long-jump team and as a relay team alternate. But at the Olympics in Barcelona, Lewis beat Powell with a jump of 28 feet 51/2 inches to win his third long-jump gold. He led the relay team to a new world record, just as he had in Los Angeles. "This was my best Olympics," he said--two gold medals, no controversy.

Ever since 1979, when a young Lewis beat his aging idol Williams, he would vowed to stop running once he was past his prime. By 1996, it looked like the time might have come for him to take his own advice. That March, he finished last in a 60-meter semi-final heat at one meet. But he was determined to make the Olympic team once more. In the Olympic trials, he almost failed to qualify as a long-jumper, but pulled it out with a 27-foot, 21/2-inch jump. At the Olympics in Atlanta, at age thirty-five, with gray peppering his hair, he stunned the crowd and himself with a 27-foot, 10 3/4-inch jump, winning his fourth long-jump gold medal. It was "better than all the others," he told a People reporter. "All the others, I was expected to win. This time I was a competitor. Before I was an icon."

Lewis retired from track and field in 1997 at a ceremony during halftime of a football game at his old alma mater, the University of Houston. His nine Olympic gold medals leave him tied with 1920s Finnish runner Paavo Nurmi for the most ever. In 1999, Sports Illustrated named him the best American Olympic athlete of the 20th century.

Today, Carl Lewis lives in Los Angeles. Since retiring from sports, he has been co-owner of a Houston restaurant and created his own line of sportswear, named SMTC after his old Santa Monica Track Club. In 1999, Texas Monthly reported that he was still running twice a week, as well as lifting weights and cycling.

Lewis is pursuing an acting career. He played a security guard in the 2002 made-for-TV movie Atomic Twister, and he will appear in the science-fiction movie Alien Hunter, scheduled for release in 2003.

AWARDS

1979, New Jersey long jumper of the year; 1980, Indoor and outdoor NCAA long-jump titles; 1981, Sullivan Award for nation's top amateur athlete; 1983, Won three events at national track championships; 1983, Associated Press Male Athlete of the Year; 1984, Four gold medals at Olympics; 1984, Associated Press Male Athlete of the Year; 1985, Jesse Owens Award; 1988, Two gold medals and one silver medal at Olympics; 1991, World record of 9.86 seconds in 100-meter dash; 1992, Two gold medals at Olympics; 1996, Fourth Olympic long-jump gold medal; 1999, Named greatest U.S. Olympian of the 20th century by Sports Illustrated; 2001, Inducted into National Track and Field Hall of Fame.

CHRONOLOGY

* 1961 Born July 1 in Birmingham, Alabama

* 1980 Wins NCAA long-jump titles

* 1980 Named to U.S. Olympic team (but U.S. boycotts Olympics)

* 1981 Breaks indoor long-jump world record

* 1984 Wins four gold medals at Olympics in Los Angeles

* 1985 Releases album, The Feeling That I Feel

* 1987 Declares that several top athletes are using steroids

* 1988 Wins two gold medals and one silver at Olympics in Seoul, including gold in 100-meter dash after Ben Johnson tests positive for steroids

* 1989 Testifies about steroids in sports before Congress

* 1990 Publishes autobiography, Inside Track

* 1991 Breaks 100-meter world record, but loses long jump when Mike Powell sets new world record at Tokyo World Track Championships

* 1992 Wins third long-jump gold medal at Olympics in Barcelona

* 1996 Wins fourth long-jump gold medal at Olympics in Atlanta

* 1997 Retires