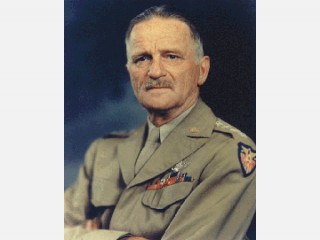

Carl Spaatz biography

Date of birth : 1891-06-28

Date of death : 1974-07-13

Birthplace : Boyerstown, Pennsylvania

Nationality : American

Category : Politics

Last modified : 2011-01-24

Credited as : Military general, Chief of Staff,

Carl Spaatz was an early advocate of the military applications of air power. He directed U.S. strategic bombing campaigns in both Europeand the Pacific during World War II.

The career of Carl Spaatz paralleled the development of military air power during the twentieth century. He entered the military in the early days of aviation and ended his career in the era of jet engines, rocketry, and nuclear weapons. Spaatz played several roles in this development, first as a proponent of aircraft as a weapon, and finally in refining the techniques and objectives of strategic aerial operations.

Carl Andrew Spaatz was born into a German immigrant family in Boyerstown, Pennsylvania on June 28, 1891. His father was a printer who also participated in local politics, once holding the position of state senator. Spaatz graduated from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in 1914, where he acquired the nickname, "Tooey," which was to remain with him for the rest of his life. After leaving the Academy, Spaatz was assigned to Schofield Barracks in Hawaii. Spaatz's second posting was to San Diego, where he learned to fly.

During the U.S. pursuit of the forces of Pancho Villa in Mexico in 1916, Spaatz served as one of America's first military aviators. At the time, the Army did not view aircraft as a means for delivering weapons to a target, but instead used them strictly for reconnaissance purposes. In fact, the Army Air Service was a part of the Signal Corps prior to World War I.

Spaatz was transferred to France following the U.S. entry into World War I in 1917. He was assigned to a training program to learn about the more aggressive uses of military aviation being made by both Allied and German forces. Bored by his training, Spaatz flew unauthorized missions with a British combat air unit and managed to shoot down two German aircraft during one of his flights. Despite his insubordination, Spaatz was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for this exploit. By war's end, he had been promoted to the rank of colonel.

In the years following World War I, military leaders debated the role of aircraft in future conflicts. Technological limitations restricted aircraft to relatively low speeds, altitudes, and payloads. It was extremely difficult to hit targets with bombs dropped from a plane. In such an atmosphere, many experts felt that aircraft would never be capable of playing a major military role, while others thought that technological advances would make aircraft the decisive factor in future conflicts.

The major early advocate of air power in the U.S. Army was the controversial Billy Mitchell, who staged a dramatic demonstration of offensive capabilities of aircraft by bombing captured German battleships in the early 1920s. Mitchell's activities angered the military establishment, and he was subjected to a court martial. Spaatz appeared as a witness on his behalf. Mitchell's eventual conviction represented a victory for opponents of expanded use of air power. Spaatz's identification with Mitchell ensured that promotions would be rare until the Army's overall attitude changed.

Throughout the 1920s and early 1930s, Army aviators staged a series of publicity flights to set aviation records and demonstrate to the public, and to their own superior officers, the expanding capabilities of aircraft. Spaatz participated in several such flights, including a 1929 endurance flight that featured 151 consecutive hours in the air and several in-flight refuelings. This sort of practical demonstration, combined with the continued development of military aircraft by other world powers, eventually led to the adoption of many of Mitchell's concepts and ensured the continuing development of U.S. military aviation.

As the U.S. military gradually accepted a broader role for aircraft, Spaatz was appointed to the Army Command and General Staff College in Leavenworth, Kansas, in 1935. This represented an opportunity to advance his career, but was considered a less desirable appointment than command of a field unit or a posting to the Tactical School at Maxwell Field. Spaatz completed his course and was recognized as one of the Army's leading experts on the uses of airpower on the eve of World War II.

Although the use of aircraft to bomb targets on the land and sea was generally accepted by military authorities in the 1930s, debate still raged on the question of the strategic uses of air power. Advocates of strategic bombing, which targets the enemy's economic infrastructure, argued that such bombing could win a war on its own. Opponents, however, doubted the ability of aircraft to create enough damage to appreciably affect the military capabilities of a large nation. The debate regarding the efficacy of strategic bombing continues to the present day.

Advocates of strategic bombing had been successful enough to ensure that all belligerent nations possessed at least some strategic bombing capabilities at the outset of World War II. Furthermore, the Spanish Civil War and the Sino-Japanese conflict during the 1930s had shown yet another use for strategic aircraft: terror bombing against civilian targets to lessen a nation's will to resist. This form of bombing was also practiced in the early stages of World War II by the German Luftwaffe, which conducted terror operations against Rotterdam in the Netherlands and London, England. Given his interest in, and advocacy of, strategic bombing, Spaatz was assigned to London at the height of the Battle of Britain during the spring and summer of 1940. His assignment was to observe the tactics and affects of the German bombing campaign, and the countermeasures employed by the British to stop it.

The eventual German defeat in the Battle of Britain demonstrated the limitations of terror bombing as a means of defeating a belligerent nation. Furthermore, German attacks on British economic and military infrastructure, while somewhat more successful, also failed to produce a decisive result. Analysis of the battle by British military aviation expert Sir Solly Zuckerman revealed that increased use of aerial photography to both identify targets for strategic bombing and analyze the extent of damage caused by such bombing could have increased the effectiveness of the German aerial offensive. Spaatz became a proponent of systematic analysis as proposed by Zuckerman, and following his tenure in England, he was promoted to the position of chief of the Army Air Forces Materiel Division. He served in this capacity until the U.S. entry into the war in December 1941.

Spaatz was promoted to the rank of major general in January 1942, and was placed in command of the Eighth U.S. Army Air Force, operating out of England, in July of that year. The Eighth Air Force commenced bombing raids on targets in continental Europe the following month. With his new command scarcely up-and-running, Spaatz was transferred to the position of Allied Air Forces Commander, to support the amphibious landing of U.S. troops in North Africa in November 1942. This command was reorganized in February 1943, and Spaatz became subordinate to British Air Marshall Tedder. However, he nonetheless received a promotion to the rank of lieutenant general in March 1943. In December of that year, Spaatz was transferred back to England and named commander-in-chief of the U.S. Strategic Air Forces in Europe.

Spaatz's experiences in the Mediterranean, which had included the suffering of heavier-than-expected losses in the attempt to bomb the German oil production facilities at Ploesti, Romania, had led him to demand the development of a long-range fighter aircraft capable of protecting bombers throughout their missions. Such an aircraft, the P-51 Mustang, became available in 1944, and the Allied strategic bombing program against Germany accelerated.

Zuckerman and Spaatz, drawing on their experiences early in the war, advocated precision daylight bombing of carefully selected targets designed to cripple Germany's fuel production and transportation capabilities. This approach was in direct contrast to that used by the British earlier in the war. The British had used nighttime bombing of entire areas of German cities, a method which combined elements of both strategic and terror bombing, while minimizing British losses. Furthermore, the British had focused on destroying military manufacturing facilities. The development of long-range fighter aircraft greatly reduced the risk of daylight bombing and made Spaatz's approach more viable as the war progressed. Nevertheless, the British continued their night area bombing campaign throughout the war with Spaatz's approval, since this, in conjunction with the U.S. daylight campaign, made the bombing of Germany continuous. Unfortunate byproducts of strategic bombing, even the "precision" bombing done by Spaatz's command during the daylight hours, were the killing of civilians and the destruction of civilian properties.

To facilitate the amphibious invasion of France, all Allied air forces were placed under the direct command of Dwight Eisenhower from April to October 1944, thus putting Spaatz's strategic bombing campaign on hold for a time. During the Normandy battles, airpower scored one its most significant victories over ground troops during the reduction of the Falaise Pocket. Shortly after the D-Day landings on June 6, 1944, Allied air superiority over the battlefield was so complete that Spaatz's forces were authorized to continue their attacks on German fuel production facilities and transportation hubs. These attacks continued until the war's end in May 1945, with a level of success that is debated to this day. In June 1945, Spaatz was transferred to oversee U.S. strategic bombing operations in the Pacific.

Strategic bombing of Japan had proven a difficult prospect. Although Japanese defenses against U.S. bombers were nearly nonexistent, the fragmentation of Japanese industry into small facilities and the sheer size of Japanese cities made targeting nearly impossible. General Curtis Lemay, who commanded the strategic bombing effort in the Pacific until Spaatz's arrival, devised a macabre solution to the problem. By test bombing a replica of a Japanese village constructed in the Nevada desert, Lemay discovered that typical Japanese houses, which were constructed of wood and paper, were particularly vulnerable to a combination of fragmentation bombs followed by incendiaries. Lemay's methods took area bombing to its most devastating form, destroying Japanese industry by burning huge portions of Japanese cities. Civilian losses caused by this type of bombing were catastrophic, exceeding 80,000 killed in one raid on Tokyo alone. Spaatz approved Lemay's methods upon taking command. He also presided over the use of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945. Significantly, the Japanese did not surrender immediately upon realizing that Hiroshima had been attacked with a nuclear device, since fewer people had been killed than in many of the earlier, conventional firebombing raids.

In the years following World War II, Spaatz continued to advocate strategic bombing as a method of warfare. Although postwar analyses revealed that German and Japanese military production had continued to increase nearly until war's end, despite the visible destruction of their national infrastructures, the advent of nuclear weapons made strategic bombing a more potent weapon than ever before. Spaatz was made commander of the U.S. Army Air Force in 1946. He became the first chief of staff of the U.S. Air Force following its establishment as a separate service in 1947. Spaatz retired from the Air Force in 1948 and became a national security affairs correspondent for Newsweekmagazine. He also served as chairman of the Civil Air Patrol and the International Reserve Committee following his retirement. Spaatz died in Washington, DC on July 13, 1974.

A Biographical Dictionary of World War II, edited by Chrsitopher Tunney, St. Martin's Press, 1972.