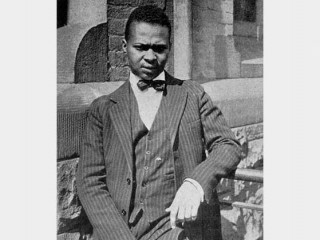

Countee Cullen biography

Date of birth : 1903-05-30

Date of death : 1946-01-09

Birthplace : Louisville, Kentucky, United States

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2010-08-20

Credited as : Poet and writer, poet of the Harlem Renaissance,

0 votes so far

One of the leading poets of the Harlem Renaissance, Countee Cullen was a master of conventional poetic art forms and an ardent admirer of nineteenth-century English poet John Keats. Inspired by European sonnet form, works of classical antiquity, and Biblical imagery, Cullen sought to create poetry that transcended the boundaries of race. "If I am going to be a poet at all," stated Cullen in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in 1924, "I am going to be a Poet and not Negro Poet." Although unable to escape the reality of race in life or art, Cullen's universal vision yielded poetry imbued with both inner torment and beauty, which addressed the black artist's search for expression in the modern Western World.

From Kentucky to New York

Countee Leroy Porter was born on May 30, 1903, in Louisville, Kentucky; some sources suggest that he was born in New York City or Baltimore, Maryland. Raised by Mrs. Porter, a woman thought to be his grandmother, Countee moved to New York City around the age of nine, taking up residence in a Harlem apartment not far from the Salem Methodist Episcopal Church. When Mrs. Porter died in 1918, a member of Salem's congregation urged the church's pastor, Reverend Frederick Asbury Cullen, to adopt Countee. Impressed by the precocious and well-mannered child, the Reverend and Mrs. Frederick Cullen adopted Countee and gave him a room in Salem's quiet 14-room parsonage.

Although the adoption was never legalized, Cullen became deeply devoted to his new parents. Provided with a sense of physical and emotional security, he quickly adapted to the quiet religious atmosphere of "Mother Salem." In his adoptive father's library, Cullen began to explore the world of books and literature. Though his early years were spent in rigorous study, Cullen enjoyed the family's summer trips to Maryland and New Jersey.

On February 4, 1918, Cullen enrolled in Dewitt Clinton High School, a highly regarded, predominately white, boy's school. An excellent student--he was elected to the school's honor society, Arista--Cullen worked on the school's literary magazine, Magpie, eventually becoming the associate editor. He studied Latin and read the works of nineteenth-century English poets Lord Byron, Alfred Tennyson, and African-American poet Paul Lawrence Dunbar. Cullen's "Song of the Poets," published in Magpie in 1918, emerged as a tribute to the great American and English poets. Another high school poem, "I Have a Rendezvous with Life"--based upon Alan Seeger's "I Have a Rendezvous with Death"--earned him first prize in a citywide poetry contest sponsored by the Empire Federation of Women's Clubs.

A popular student, Cullen served as class vice president, treasurer of the Inter-High School Poetry Association, and was a member of the debating society. In 1922 Cullen graduated from Dewitt Clinton and entered New York University on a State Regents Scholarship. Outside his regular academic studies in Latin, Greek, English, French, math, physics, geology, and philosophy, Cullen dedicated himself to writing poetry.

Studying under English scholar Hyder E. Rollins, Cullen acquired a passion for the nineteenth-century English poet John Keats. The romantic ballad-style of Keats had a profound impact on Cullen's career. Writer Arna Bontemps recalled years later, in The Harlem Renaissance Remembered, that when he first met Cullen, he told "me that John Keats was his god." In 1923, he was awarded second prize in the Witter Bynner Poetry Contest for "The Ballad of the Brown Girl." This piece is Cullen's earliest attempt to subvert Western form and social associations in order to portray the ways in which racist practices operate in the lives of African Americans. Unlike the classical portrait of the brown girl of Western poetics who is marked only by her low social status, Cullen's brown girl is literally killed by the social realities of race. Although she marries her white lover, she is strangled by her husband in defense of white womanhood. Cullen continued to win recognition in the Witter Bynner Poetry Contest, in 1924 receiving honorable mention for his entry. He finally won first prize in 1925 for "One Who Said Me Nay," a poem which was won second prize in Opportunity's literary competition.

Like many of his contemporaries, including his friend Langston Hughes, Cullen increasingly became interested in spending time abroad, especially in France. He promised to go along when Hughes embarked for France in 1924, but eventually decided to remain in the States to earn money to continue his education. Remaining at home proved to be the best decision because 1925 was a pivotal year in Cullen's life. In that year, he was elected to Phi Beta Kappa and continued to win academic and literary honors. Cullen was awarded Poetry Magazine's John Reed Memorial Prize for his poem, "Threnody for a Brown Girl." He also won Crisis magazine's Spingarn Contest for "Two Moods of Love," having won the attention of the magazine's editor, W.E.B. Du Bois.

By the time Cullen graduated from New York University in 1925, Harper and Row was in the process of publishing Color, his first volume of poems. The collection includes some of the poems that established Cullen as a true voice of the Harlem Renaissance. "Incident" and "Yet Do I Marvel," both poems about the difficulties of simply being black in America, are among his best known and most often anthologized poems. True to Cullen's fascination with contrasts, the volume also includes pieces on Paul Laurence Dunbar and "To John Keats, Poet." J. Saunders Redding wrote in his essay, "The New Negro Poet in the Twenties," that despite the confusion that would dominate succeeding volumes of poetry, Color is clearly about race, "the biggest, single most unalterable circumstance in the life of Mr. Cullen." Critically acclaimed in white and black literary circles, Color made Cullen the most nationally celebrated African-American poet since Paul Lawrence Dunbar. Divided into three sections, Color contains seventy-four poems, one-third of which deal with racial themes. Rooted in traditional sonnet form, the book's poems reveal what S.P. Fullinwinder described in The Mind and Mood of Black America, as a struggle between "myth and modernity"--an inner struggle between the fundamentalist faith of his adoptive father and the pagan impulse of his poetic vision. One of the finest and most famous poems of the volume, "Heritage," represents this struggle between faith and racial identity. The line "So I lie ..." appears five times, a recurrent phrase intended to illustrate the mystical images of Christ and Africa and the true search for spirituality and ancestral heritage.

Unlike other Harlem Renaissance poets such as Langston Hughes and Sterling Brown, Cullen did not utilize the rhythms of jazz or modern, free verse style. Cullen wrote in Opportunity that "I wonder if jazz poems really belong to that dignified company, that select and austere circle of high literary expression we call poetry." As Gerald Early pointed out in My Soul's High Song, Cullen's criticism of jazz poetry stemmed from the fact that he "believed jazz to be an insufficiently developed, insufficiently permanent art form to use as an aesthetic for poetry." Color sold more than 2,000 copies, establishing Cullen as a major writer of the era. It also brought him to the attention of the Harlem Renaissance literati including Alain Locke, who included Cullen's work in his anthology, The New Negro (1926), editor Charles Johnson, who hired him as an assistant editor for Opportunity, and writer James Weldon Johnson.

The year 1927 saw the publication of Cullen's Copper Sun and Ballad of a Brown Girl: An Old Ballad Retold. Although Copper Sun won the general approval of critics, many agreed that it lacked the intensity of Color. Cullen dedicated Copper Sun to Yolande Du Bois, daughter of famous National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) founder and scholar W.E.B. Du Bois. Introduced to Yolande in the summer of 1923, Cullen's courtship greatly pleased her father. But despite her prestigious social position, Yolande was, according to historian David Levering Lewis, "a kind" yet "plain women of modest intellectual endowment," who, as it was well known among Harlem circles, was infatuated with jazz band leader Jimmie Lunceford. Nevertheless, Yolande and Cullen were married by Reverend Cullen on April 9, 1928, in the Salem Methodist Church. The ceremony became a grand showing of African-American wealth and talent from around the country. Among the ushers were the famous black poets Arna Bontemps and Langston Hughes.

Not long after the wedding, Cullen traveled to France on a Guggenheim fellowship. Leaving his wife, who was to join him later in Paris, Cullen departed for Europe on June 30th with his father and close friend Harold Jackman. Taking up residence in a small hotel in the Trianon on the Avenue du Maine, Cullen found Paris to be an exciting and colorful city. In Paris he often met with a group of African-American artists, including writer Eric Walrond and sculptor Augusta Savage.

Aside from writing, Cullen enrolled at the Sorbonne to study French literature. When Yolande joined Cullen in July of 1928, the couple decided to end their relationship. After Yolande returned to America, Cullen stayed in Paris and completed The Black Christ and Other Poems. One of the many poems dedicated to the painful break-up with his wife, "Foolish Heart" was a poignant example of Cullen's painful reflection: "Be still, heart, cease those measured strokes; / Lie quiet in your hollow bed; / This moving frame is but a hoax; / To make you think you are not dead."

Embraces Both White and Black Cultures

Because of Cullen's success in both black and white cultures, and because of his romantic temperament, he formulated an aesthetic that embraced both cultures. He came to believe that art transcended race and that it could be used as a vehicle to minimize the distance between black and white peoples. When he chose as his models poet John Keats and to a lesser extent A.E. Housman, he did so not consciously to curry favor with white America but for four logical reasons: First, though there had been Afro-American poets, there was not yet an Afro-American poetic tradition--in any meaningful sense of the term--to draw upon. Second, the English poetic tradition was the one that was available to him--the one that had been taught to him in schools he attended. Third, he felt challenged to demonstrate that a black poet could excel within that traditional framework. And fourth, he felt absolutely free to choose as exemplars any poets in the world with whom he sensed a temperamental affinity (and he certainly had that affinity with Housman and, especially, Keats). In addition, he shared their romantic self-involvement; he had an ego that was sensitive to the slightest tremors and that needed expression to remain whole, and like Keats he had to believe in human perfectibility.

In poems such as "Heritage" and "Atlantic City Waiter," Cullen reflects the urge to reclaim African arts--a phenomenon called "Negritude" that was one of the motifs of the Harlem Renaissance. The cornerstone of his aesthetic, however, was the call for black-American poets to work conservatively, as he did, within English conventions. In his foreword to Caroling Dusk, Cullen observed that "since theirs is ... the heritage of the English language, their work will not present any serious aberration from poetic tendencies of their times." Braving the wrath of less moderate peers, he further stated that "negro poets, dependent as they are on the English language, may have more to gain from the rich background of English and American poetry than from any nebulous atavistic yearnings toward an African inheritance." Even the subtitle of the collection, An Anthology of Verse by Negro Poets, reflects his belief in the essential oneness of art; it implies no distinction between white poetry and black poetry, and it assumes there is only poetry, which in the case of Caroling Dusk is simply composed by Afro-American writers.

His dedication to oneness led Cullen to be cautious of any black writer's work that threatened to erect rather than pull down barricades between the races. Thus, in a "Dark Tower" column in which Cullen reviewed Langston Hughes's The Weary Blues, Cullen pressed Hughes not to be a "racial artist" and to omit jazz rhythms from his poems. In a later column he prodded black writers to censor themselves by avoiding "some things, some truths of Negro life and thought ... that all Negroes know, but take no pride in." For Cullen, showcasing unpleasant realities would "but strengthen the bitterness of our enemies" and thereby weaken the bridge of art between blacks and whites.

A paradox exists, however, between Cullen's philosophy and writing. While he argued that racial poetry was a detriment to the color-blindness he craved, he was at the same time so affronted by the racial injustice in America that his own best verse--indeed most of his verse--gave voice to racial protest. In fact, the title of Cullen's 1925 collection, Color, was not chosen unintentionally, nor did Cullen include sections with that same title in later volumes by accident. Both early and late in his career he was, in spite of himself, largely a racial poet. This is evident throughout Cullen's works from the Color pieces and the introduction of racial violence into his 1927 work The Ballad of the Brown Girl: An Old Ballad Retold to the poems that he selected for the posthumously published On These I Stand: An Anthology of the Best Poems of Countee Cullen, of which substantially more than half are racial poems.

Of the six identifiable racial themes in Cullen's poetry, the first is Negritude, or Pan-African impulse, a pervasive element of the 1920s international black literary movement that scholar Arthur P. Davis in a Phylon essay called "the alien-and-exile theme." Specific examples of this motif in Cullen's poetry include his attribution of descent from African kings to the girl featured in The Ballad of the Brown Girl as well as the submerged pride exhibited by the waiter in the poem "Atlantic City Waiter" whose graceful movement resulted from "Ten thousand years on jungle clues." Probably the best-known illustration of the Pan-African impulse in Cullen's poetry is found in "Heritage," where the narrator realizes that although he must suppress his African heritage, he cannot ultimately surrender his black heart and mind to white civilization. "Heritage," like most of the Negritude poems of the Harlem Renaissance and like political expression such as Marcus Garvey's popular back-to-Africa movement, powerfully suggests the duality of the black psyche--the simultaneous allegiance to America and rage at her racial inequities

Four similar themes recur in Cullen's poems, expressing other forms of racial bias. These include a kind of black chauvinism that prevailed at the time and that Cullen portrayed in both The Ballad of the Brown Girl and The Black Christ, when in those works he judged that the passion of blacks was better than that of whites. Likewise, the poem "Near White" exemplifies the author's admonition against miscegenation, and in "To a Brown Boy" Cullen propounds a racially motivated affinity toward death as a preferred escape from racial frustration and outrage. Another poem, "For a Lady I Know," presents a satirical view of whites obliviously mistreating their black counterparts as it depicts blacks in heaven doing their "celestial chores" so that upper-class whites can remain in their heavenly beds.

Using a sixth motif, Cullen exhibits a direct expression of irrepressible anger at racial unfairness. His outcry is more muted than that of some other Harlem Renaissance poets--Hughes, for example, and Claude McKay--but that is a matter of Cullen's innate and learned gentility. Those who overlook Cullen's strong indictment of racism in American society miss the main thrust of his work. His poetry throbs with anger as in "Incident" when he recalls his personal response to being called "nigger" on a Baltimore bus, or in the selection "Yet Do I Marvel," in which Cullen identifies what he regards as God's most astonishing miscue that he could "make a poet black, and bid him sing!" In addition to his own personal experiences, Cullen also focuses on public events. For instance, in "Scottsboro, Too, Is Worth Its Song," he upbraids American poets, who had championed the cause of white anarchists in the controversial Sacco-Vanzetti trials, for not defending the nine black youths indicted on charges of raping two white girls in a freight car passing through Scottsboro, Alabama, in 1931.

In The Book of American Negro Poetry, author James Weldon Johnson explained with acute sympathy Cullen's compulsion to write poetry that seems to fly in the face of his declarations against poetry of race. Johnson wrote: "Strangely, it is because Cullen revolts against ... racial limitations--technical and spiritual--that the best of his poetry is motivated by race. He is always seeking to free himself and his art from these bonds. He never entirely escapes, but from the very fret and chafe he brings forth poetry that contains the quintessence of race consciousness."

Cullen, then, was a forceful but genteel protest poet; yet, he was much more. He was also consistent in his intention to write good traditional poetry for the social purpose of showing what common sense should have told white Americans but what they still demanded be proven to them--that blacks could write poetry and write it as well as anyone. To that end, much of Cullen's poetry deals with such universal subjects as faith and doubt, love, and mortality.

On the subject of religion, Cullen waywardly progressed from uncertainty to Christian acceptance. Early on he was given to irony and even defiance in moments of youthful skepticism. In "Heritage," for example, he observes that a black Christ could command his faith better than the white one. When he was twenty-four, he provided a third-person description of himself in which he commented that his "chief problem has been that of reconciling a Christian upbringing with a pagan inclination. His life so far has not convinced him that the problem is insoluble." But before very long, his grandmother Porter's influence and that of the Cullen rectory won out. Outrage over racial injustice notwithstanding, he had fairly well controlled the "pagan inclination" in favor of Christian orthodoxy by 1929, when he published The Black Christ, and Other Poems. In the opening of the book's narrative title poem, the protagonist sings of embracing God in spite of certain earthly obstacles that he summarizes as "my country's shame." The speaker's brother has been beaten to death by a white lynch mob for an innocent relationship with a white woman; the narrator's resentment toward a savior who allows such evil to occur is overcome by his mother's proclamation of her unshakable faith, and any residue of doubt disappears when the murdered brother is resurrected. At the end the family is left to prosper in its piety. Furthermore, among the few previously unpublished poems that Cullen selected for inclusion in the posthumously published collection On These I Stand is one that confirms his continuing religious commitment as a way to cope with the injustices and disappointments of his life. Written during World War I, "Christus natus est" asserts that amid all the tragedy of war "The manger still / Outshines the throne" and that "Christ must and will / Come to his own."

To understand Cullen's treatment of love it is necessary first to examine the effete--weak or effeminate--quality of many of his love poems. David Levering Lewis, in When Harlem Was in Vogue, asserted that "impotence and death run through [Cullen's] poetry like dark threads, entangling his most affirmative lines." In general, Cullen's love poetry is clearly characterized not only by misgivings about women but also by a distrust of the emotion of heterosexual love. His "Medusa" and "The Cat," both contained in The Medea, and Some Poems, illustrate this vision of male-female relationships. In Cullen's version of the ancient myth, it is not the hideousness of Medusa that blinds the men who gaze upon her, but rather her beauty. So great is the destructive power of the attractive female that the narrator in "The Cat" imagines in the animal "A woman with thine eyes, satanic beast / Profound and cold as scythes to mow me down." Male lovers, on the other hand are often portrayed as sickly with apprehension that a relationship is about to be ended either by a fickle partner or by death. In "If Love Be Staunch," for example, the speaker warns that love lasts no longer than "water stays in a sieve" and in "The Love Tree" Cullen portrays love as a crucifixion whereby future lovers may realize that "'Twas break of heart that made the love tree grow." What Lewis identified in Cullen's love poems as a "corroding suspicion of life cursed from birth" may have resulted from Cullen's alleged homosexuality.

Cullen's treatment of death in his writing was shaped by his early encounters with the deaths of his parents, brother, and grandmother, as well as by a premonition of his own premature demise. Running through his poems are a sense of the brevity of life and a romantic craving for the surcease of death. In "Nocturne" and "Works to My Love," death is readily accepted as a natural element of life. "Threnody for a Brown Girl" and "In the Midst of Life" portray even warmer feelings towards death as a welcome escape. And in poems such as "Only the Polished Skeleton" death is gratefully anticipated to bring relief from racial oppression: A stripped skeleton has no race; it can but "measure the worth of all it so despised." Looking forward to death, Cullen meanwhile accepted sleep as an effective surrogate. In the poem "Sleep" he portrays slumber as "lovelier" and "kinder" than any alternative. It is both a feline killer and gentle nourisher that suckles the sleeper: "though the suck be short 'tis good." In April, 1943, less than three years before he died of uremic poisoning, Cullen related in "Dear Friends and Gentle Hearts" that "blessedly this breath departs."

After 1929 Cullen's production of verse dropped off dramatically. It was limited to his translation of Euripides' play Medea, which appeared along with some new poems in his 1935 collection The Medea, and Some Poems and later with half a dozen previously unpublished pieces that were included in his posthumously published collection, On These I Stand. A complexity of reasons contributed to the dimming of his poetic star. The Harlem Renaissance required a white audience to sustain it, and as whites became preoccupied with their own tenuous situation during the Great Depression, they lost interest in the Afro-American arts. Also, Cullen's idealism about building a bridge of poetry between the races had been sorely tested by the time the 1920s ended. Moreover, he seemed affected by legitimate doubts concerning his growth as a poet. In "Self Criticism" he reflected whether he would go on singing a "failing note still vainly clinging / To the throat of the stricken swan."

While his supporters continued to defend him on racial rather than literary grounds, his detractors gradually increased in numbers with the publication of each successive collection of his poetry. Harry Alan Potamkin, in a New Republic review of Copper Sun, found that Cullen had not really progressed since Color and that the poet had "capitalized on the fact of race." The reviewer concluded, in fact, that Cullen's poetry "begins and ends with a epithet skill." With the appearance of The Black Christ, and Other Poems in 1929, Nation's Granville Hicks joined the chorus of critics expressing reservations and remarked that "in general, Mr. Cullen's talents do not seem to be developing as one might wish."

Turns from Poetry

For a combination of causes, then, beginning in the early 1930s Cullen largely curtailed his poetic output and channeled his creative energy into other genres. He wrote a novel, One Way to Heaven, published in 1932, but its poor critical reception made it his only novel. The book reveals a flair for satire in its secondary plot, which centers around the Harlem salon of the irrepressible hostess Constancia Brandon; one particularly effective episode features a white intellectual bigot who is invited to read his tract, "The Menace of the Negro to Our American Civilization," to an audience of mainly black intellectuals. The novel itself, however, suffers from a fatal structural flaw. Cullen never successfully integrated the secondary plot--a takeoff on his own experience in Harlem intellectual circles--with the major story line, a melodrama in which itinerant con man Sam Lucas undergoes a fake religious conversion to edge his way into a Harlem congregation; marries and then cheats on his sweet young wife; and finally, on his death bed undergoes a change of heart. The characters in the main plot are generally based on stereotypes common in black-American folklore--the fast-talking trickster and the sagacious saintly old aunt, for example. Although Cullen displays some compassion toward them and a good deal of good-natured wit in dealing with the satirical figures, the two plots never adequately come together. As Rudolph Fisher said in a New York Herald Tribune review of One Way to Heaven, it was as if Cullen were "exhibiting a lovely pastel and cartoon on the same frame."

When thirty-one-year-old Cullen turned to teaching in 1934, he was determined to find some way other than literature to contribute to social change, but he did not abandon writing entirely. In 1935 he published his version of Medea (with the speeches and choral passages curiously attenuated) and collaborated with Harry Hamilton on "Heaven's My Home," a dramatic adaptation of One Way to Heaven. The play, which was never published, is actually more contrived than Cullen's novel, but unlike the original work, "Heaven's My Home" manages to integrate the two plots by introducing a sexual relationship between the protagonists Lucas and Brandon.

Toward the end of his life, in the 1940s, Cullen was relatively successful as a dramatist. With another collaborator, Owen Dodson, he worked on several projects, including "The Third Fourth of July," a one-act play printed in Theatre Arts in August, 1946. During this period Cullen rejected a professorship at Fisk University and instead remained in New York to work with Arna Bontemps on a dramatic version of her novel God Sends Sunday. Cullen, who suggested the adaptation, made this endeavor the center of his life, but the enterprise caused him much grief. By 1945 the play had become the musical "St. Louis Woman," and celebrated performer Lena Horne was expected to star in its Broadway and Hollywood productions. Then disaster struck. Walter White of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) argued that the play, set in the black ghetto of St. Louis and featuring lower-class and seedy characters, was demeaning to blacks. Cullen was blamed for revealing the seamy side of black life, the very thing he had warned other black writers not to do. Many of Cullen's friends refused to defend him; some joined the attack, which was patently unjust. Admittedly, greed and criminality figure in the play, which focuses on the struggle between overbearing salon keeper-gambler Bigelow Brown and diminutive jockey Lil Augie for the affections of Della Greene, a hard-nosed and soft-hearted beauty.

But as Cullen argued, the play really deals with human virtues--honor, love, decency, and loyalty. The controversy rounding it wore on, however, until 1946. In March of that year, "St. Louis Woman" finally premiered on Broadway, featuring songs by Johnny Mercer and Harold Arlen such as "Come Rain, Come Shine" and making singer Pearl Bailey a star. Unfortunately, Cullen had died almost three months earlier and was to be remembered primarily for the poems he had written in his twenties when he was one of Harlem's brightest luminaries.

During 1942 Cullen was interviewed in his former alma mater's publication, Magpie, by young Dewitt Clinton high school student James Baldwin, who would himself become a brilliant writer. In his summation of the condition of the black artist in America, Cullen told Baldwin that "in this field one gets pretty much what he deserves. ... If you're really something, nothing can hold you back. In the artistic field, society recognizes the Negro as an equal and, in some cases, as a superior member."

Though Cullen's career as a poet had long since faded by the mid-1940s, he left behind a lifetime of works that, as Gerald Early wrote in My Soul's High Song, contributed to the "entire concept of the Harlem Renaissance and the formation of a national black culture." Quoted in J. Saunders Redding's To Make a Black Poet, Cullen stated that "the essential quality of good poetry is utmost sincerity and earnestness of purpose. A poet untouched by his times, by his environment, is only half a poet." Given the enduring impact of Cullen's work, he remains a true voice of his time and an American poetic genius.

PERSONAL INFORMATION

Given name Countee LeRoy Porter; first name pronounced "Coun-tay"; born May 30, 1903, in Louisville, KY; died of uremic poisoning, January 9, 1946, in New York, NY; buried in Woodlawn Cemetery, New York, NY; married Nina Yolande DuBois, April 9, 1928 (divorced, 1930); married Ida Mae Roberson, September 27, 1940.

WRITINGS

* POETRY

* Color (includes "Heritage," "Atlantic City Waiter," "Near White," "To a Brown Boy," "For a Lady I Know," "Yet Do I Marvel," "Incident," "The Shroud of Color," "Oh, for a Little While Be Kind," "Brown Boy to Brown Girl," and "Pagan Prayer"), Harper (New York, NY), 1925, reprinted, Arno Press (New York, NY), 1969.

* Copper Sun (includes "If Love Be Staunch," "The Love Tree," "Nocturne," "Threnody for a Brown Girl," and "To Lovers of Earth: Fair Warning"), illustrated by Charles Cullen, Harper (New York, NY), 1927.

* The Black Christ, and Other Poems (includes "The Black Christ," "Song of Praise," "Works to My Love," "In the Midst of Life," "Self Criticism," "To Certain Critics," and "The Wish"), illustrated by Charles Cullen, Harper (New York, NY), 1929.

* The Medea, and Some Poems (includes translation of Euripides' play Medea, "Scottsboro, Too, Is Worth Its Song," "Medusa," "The Cat," "Only the Polished Skeleton," "Sleep," "After a Visit," and "To France"), Harper (New York, NY), 1935.

* On These I Stand: An Anthology of the Best Poems of Countee Cullen (includes "Dear Friends and Gentle Hearts," "Christus natus est," and some previously unpublished poems), Harper (New York, NY), 1947.

* My Soul's High Song: The Collected Writings of Countee Cullen, Voice of the Harlem Renaissance, edited and with an introduction by Gerald Early, Doubleday (New York, NY), 1991.

* OTHER

* (Editor) Caroling Dusk: An Anthology of Verse by Negro Poets, illustrated by Aaron Douglas, Harper (New York, NY), 1927, reprinted, 1974.

* The Ballad of the Brown Girl: An Old Ballad Retold, illustrated by Charles Cullen, Harper (New York, NY), 1927.

* One Way to Heaven (novel), Harper (New York, NY), 1932, reprinted, AMS Press (New York, NY), 1975.

* The Lost Zoo (a Rhyme for the Young, but Not Too Young), illustrated by Charles Sebree, Harper (New York, NY), 1940, new edition illustrated by Joseph Low, Follett (Chicago, IL), 1969, new edition illustrated by Brian Pinkney, Burdett (Englewood Cliffs, NJ), 1992.

* My Lives and How I Lost Them (juvenile), illustrated by Robert Reid Macguire, Harper (New York, NY), 1942, new edition illustrated by Rainey Bennett, Follett (Chicago, IL), 1971.

* (With Owen Dodson) The Third Fourth of July (one-act play), published in Theatre Arts, 1946.

* (With Arna Bontemps) St. Louis Woman (musical adaptation of Bontemps's novel God Sends Sunday; first produced at Martin Beck Theater, New York, NY, 1946), published in Black Theatre, edited by Lindsay Patterson, Dodd, Mead (New York, NY), 1971.