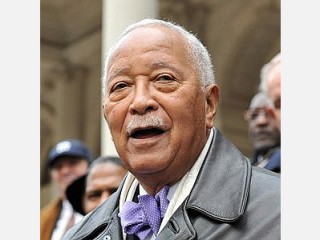

David Dinkins biography

Date of birth : 1927-07-10

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Trenton, New Jersey, United States

Nationality : American

Category : Politics

Last modified : 2011-02-17

Credited as : Politician, Mayor of New York,

After defeating incumbent Mayor Edward I. Koch in New York's 1989 Democratic mayoral primary, David Dinkins went on in November to defeat Rudolph Giuliani and become the first African American mayor of New York City.

Calm, elegant, deliberate, and dignified, David N. Dinkins overcame the suspicions of many white New Yorkers that he lacked leadership qualifications and in November of 1989 was elected the first black mayor of the United States' largest city. After announcing his candidacy in February, Dinkins became the beneficiary of a changing public attitude, one exhausted with racial strife and adjustments caused by a constricting economy. Drawing heavily on his political stronghold in Harlem, the career politician and lifelong Democrat defeated incumbent Mayor Edward I. Koch in September. In the general election he was victorious over a political neophyte, the popular district attorney Rudolph W. Giuliani. Once in office, Dinkins faced the intimidating task of healing a city suffering from fiscal and racial hemorrhaging. The results have received mixed reviews, with supporters praising Dinkins for calming a populace that threatened to explode more than once, and detractors arguing that he has acted timidly at a time when the city was crying out for forceful leadership.

Celestine Bohlen expressed in the New York Times: "David Dinkins comes to the office of mayor after three decades of loyal, quiet service to the Democratic party— making him a man who is a groundbreaker and very much bound by tradition. In a race against two high-profile opponents, Mr. Dinkins was the candidate of moderation, a middle-of-the-road choice for a city that seemed eager to lower its own decibel level. His strategy was to soothe, not excite—and it worked."

Perceiving that the city he likes to call "our town" was ready for a candidate that would "take the high road," Dinkins led a campaign that was notable less for what he said than the way he said it. His English was formal and almost stilted, delivered in a calm baritone laden with "one oughts" and "pray tells." He did not raise his voice and unlike many politicians, spoke the same language at a breakfast meeting on Wall Street as he did at a street rally in Bensonhurst, a volatile area of the city. He fared well in comparison to Koch, known for his divisive politicking, and Giuliani, who transferred his prosecutorial style to the campaign trail.

Dinkins has been called a man of deep convictions by his admirers, although few concrete programs can be linked to those convictions. Others have called him a political Bill Cosby: "Dinkins projects the kind of personality that's not threatening to whites and is acceptable to blacks," Representative Floyd H. Flake, a black Democrat from Queens, told the New York Times. Yet throughout his career he has received only marginal support from black political groups or voters outside his Harlem base, losing as many elections as he has won. The "rap" against him cites his inadequate support for minority issues.

By most accounts his finest moments in the campaign involved calming the city when it seemed on the brink of racial schism. A young white woman had been raped and brutalized by black youths in Central Park, and a black teenager had been murdered in a white ethnic Brooklyn neighborhood. In the polarized atmosphere of the summer of 1989, Dinkins emerged as a peacemaker. His image as an avuncular, deliberative leader seemed a welcome balm to New Yorkers. To appear cool and unflappable in the summer heat, Dinkins had his aides carry three or four identical linen suits, allowing for quick changes.

In Bensonhurst, where black community leaders had organized a march to protest the killing of Yusef Hawkins in August, Dinkins faced an angry crowd that booed his arrival. He managed to quiet the boos and obtain his audience's respect. According to an account by Todd Purdum in the New York Times, he approached it this way: "Let's be clear on something. There's no need for you to agree with me. You have every right to prefer someone else. But understand this also. There will come a November 7 and then there'll be a November 8, and the people will have spoken. And after they've spoken, I'm equally confident that you're going to obey and abide by that judgment."

Such moments of eloquence were rare for Dinkins. Even his supporters joked about his wooden speaking style. On the eve of the general election, in a televised candidate's debate, he was given 60 seconds to explain why he should be mayor. To do this he needed to read aloud from a prepared text. For months on the campaign trail, reporters' eyes would glaze over when he repeated, for the umpteenth time, his vision of the city's ethnic diversity as "a gorgeous mosaic." He deviated little from his script.

Dinkins's two main campaign hurdles were civil rights leader Jesse Jackson and his own personal finances. Dinkins's association with Jackson, whose private pronouncement of New York as "Hymietown" still infuriated many, limited Dinkins's support among Jewish voters. The mayoral candidate's campaign strategists, however, were able to convince a plurality of Jewish voters that Dinkins was his own man and solidly within the Democratic party tradition.

A second obstacle was the integrity issue. Dinkins paid no income taxes from 1969 through 1972, although he later paid back taxes in full with interest. He referred to the omission as an oversight. He also came under a cloud for his perceived unethical handling of his stock portfolio; he had transferred ownership to his son and substantially underreported its cash worth. Dinkins spent much time in the latter part of the campaign addressing those issues, often with visible reluctance and resentment.

Dinkins was born in Trenton, New Jersey, in 1927. His family had come from the South the previous year after pulling up roots in Newport News, Virginia. During Dinkins's early childhood, his parents separated, and he and his younger sister went with their mother to start a new life in Harlem. He returned to Trenton to attend high school, then went on to Howard University. His studies were interrupted by World War II, during which he served in the Marines. "Dink" was recalled by classmates as a fine student; media interviews with those classmates depict a young man with strong social skills, popular with one and all, and involved in a fraternity. It was at Howard that Dinkins met Joyce Burrows, a campus queen of a rival fraternity. The two eventually became engaged.

While strongly involved in social life at Howard—a primarily black college in Washington, D.C.—as an undergraduate, Dinkins occasionally ventured off campus to see movies in the Washington area. The capital was very much a segregated city at that time. An inveterate movie buff, Dinkins would don a turban and fake a foreign accent in order to enter movie theaters off limits to blacks. The episodes apparently did not stir any racial bitterness in the young man.

Soon after graduation Dinkins married his fiance in an Episcopalian church in Harlem, where the couple then set up housekeeping. Mrs. Dinkins had grown up in a very political family—her father was Daniel Burrows, former assemblyman and district leader—and provided strong encouragement for the young man to consider a political career. In 1953 Dinkins enrolled at Brooklyn Law School, entertaining the possibility of launching a political career. The young family soon moved to a state-subsidized, middle-class housing project in Harlem, where they raised two children.

Dinkins eventually complied with the wishes of his wife's parents. Introduced to J. Raymond Jones, the so-called "Harlem Fox," Dinkins became a cog in the powerful Harlem political machine, the Carver Club. The organization trained generations of young black business and political leaders and was well entrenched within the city's power structure. Dinkins took on the grunt work that is part of every campaign, awakening at dawn to hang posters at Harlem subway stops. He worked long and hard without complaint, and his dedication was duly noted. Within the Carver Club, racial rhetoric was rare, congeniality the byword. Dinkins mixed easily with politicos from all walks of life. Among his peers and cronies were Basil Paterson, Charles Rangel, and Percy Sutton, all of whom were to emerge as three of the city's most powerful black politicians. As Dinkins grew older and took on more responsibility, his associations came to include a number of the city's movers and shakers. He played tennis with them at the River Club, visited their estates in South Hampton, and vacationed in Europe at their expense.

None of this endeared Dinkins to black community leaders or younger, more activist voters. Yet as the momentum of his campaign grew, and it became clear he had a very real chance to become the city's first black mayor, misgivings gave way to racial pride. Blacks sporting "Dinkins" buttons on their lapels began turning up all over town. When his chauffeured car pulled into a black neighborhood, the excitement became palpable. A Newsday editorial writer asked Dinkins whether he feared his image was that of an Uncle Tom. He answered, "Au contraire. What I do is provide hope."

In 1965 Dinkins ran for his first elective office, representing his district in the New York State Assembly, and won. At the end of his two-year term, however, his district was redrawn, and he chose not to run again. He bided his time handling local political tasks. When Mayor Abraham Beame offered him a post in his administration as deputy mayor, Dinkins accepted—then withdrew in the midst of a media hoopla over his unpaid taxes. Dinkins paid his taxes and, still very much in the party's good graces, was hastily appointed city clerk. His responsibilities mainly involved signing marriage certificates; his salary was $71,000.

In 1977 Percy Sutton resigned as Manhattan borough president and anointed Dinkins to run for the office. Dinkins did, but lost by a wide margin. Four years later he ran again, losing once more in a landslide. In 1985 he vied a third time and was elected. The post he took over included a staff of more than 100 and an annual budget of nearly $5 million. As borough president, Dinkins did little to upset the apple cart. He put together task forces on a range of urban issues, from pedestrian safety to school decentralization. Perhaps his strongest stance was in support of community-based AIDS services.

Neil Barsky wrote in the Wall Street Journal, "By most accounts he made little of the post, and was best known among city politicians for his problems making up his mind" on budget and land-use matters. Dinkins earned a reputation as a procrastinator, withholding his opinion or his vote until he could hold lengthy, detailed briefings with aides and consultants. To the public he was deliberate, cool-headed, and rather vague, as evidenced by an answer given to New York Times reporter Todd Purdum in response to a question on streamlining the city's bureaucracy: "I cannot now set forth a specific blueprint and guarantee that we can do everything in one stop. All I'm saying is there must exist the ingenuity among us if we start off with the assumption that it's a desirable goal."

Early in his tenure, Dinkins experienced firsthand the glaring difference between a candidate who can promise the sky and an office-holder who cannot, to the dismay of some constituents, deliver all things to all people. The city Dinkins inherited, in the eyes of many political pundits, was looking more ungovernable with each passing day, presenting a string of concrete challenges to the idealism that had drawn the electorate to him during the campaign. The budget deficit was running at $1.8 billion, a national recession was robbing the city of jobs and cutting revenues, and crime continued to claim victims in cases that made the national news and further enhanced the image of New York as an archetype of urban decay.

In addition, it was by no means helpful that at a time when New Yorkers were in need of greater government services, federal aid to cities across the country had been given the budgetary ax. After being criticized for initially wavering on New York finances, Dinkins bit the bullet, avoiding deficit spending by cutting the city's work force and dramatically scaling back health, education, housing, and other social programs. These moves, while praised as fiscally prudent, had a political cost. Some claimed Dinkins hadn't done enough, particularly with the downsizing of government, and others maintained he had alienated those constituents in the labor and African American communities who had been among his most strident supporters. "I sort of get it from both sides," Dinkins was quoted as saying in Emerge. "You can't make political judgments about actions you take. You really need to make a judgment that's consistent with the correct thing to do and what's good for all people. When it comes to 'my constituency' so-called—I frankly see everyone as my constituency."

In addition to facing attacks on his financial handling of the city, Dinkins began to see the further shattering of his beloved "gorgeous mosaic." In 1991 violent protests erupted after a car in the entourage of a Brooklyn Jewish leader struck and killed a black youth in Queens. Dinkins appealed to both sides to follow the light of reason rather than cave in to emotion, stereotypes, and hate and was credited with having brokered a peace, albeit a fragile one.

A more rigorous test of his healing powers was delivered in 1992, when riots ravaged cities throughout the country in the wake of the not guilty verdict in the controversial Rodney King case, which involved the question of brutality inflicted by white police officers on a black citizen. Visiting neighborhoods most vulnerable to violent explosion, Dinkins again succeeded in deactivating a racial time bomb and earned, at least temporarily, a respite from his critics. "This was defining moment for him," state Democratic Chairman John A. Marino was quoted as saying in the New York Times. "He showed why he was elected, in a sense. I'm hearing a lot of good things about David N. Dinkins from people who a few weeks ago didn't have anything good to say about him."

Dinkins continued to have good luck in 1992, as the city prepared for the lucrative Democratic National Convention—a feather in the mayor's political cap. An unexpected budget surplus was discovered, and the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) ruled in May that the mayor had not violated federal tax rules in the 1986 stock transaction with his son. A July 2, 1992, poll indicated New Yorkers had a 41 percent favorable opinion of him, not the number of a universally loved politician, but 12 points higher than it had been in March.

Dinkins has learned, however, that luck is as fleeting in politics as it is in other fields, perhaps more so. As the 1993 election approached, Dinkins was facing a steady stream of criticism that he has hired incompetent workers to top municipal posts, that he acts reactively rather than proactively, and that, while displaying a talent for pacifying, he lacks the consistently strong leadership and stalwart vision that the city's multifaceted problems demand.