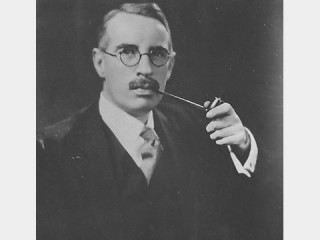

Davidson Black biography

Date of birth : 1884-07-25

Date of death : 1934-03-15

Birthplace : Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Nationality : Canadian

Category : Arhitecture and Engineering

Last modified : 2010-10-25

Credited as : Archaeologist, discovered the Peking Man,

1 votes so far

Life

Davidson Black was born in Toronto, Ontario, Canada on July 25, 1884. As a child he showed a great interest in biology, despite being born to a family associated with law. He spent many summers near or on the Kawartha Lakes, canoeing and collecting fossils. While a teenager, he made friends with First Nations people, learning one of their languages. He also tried unsuccessfully to search for gold along the Kawartha Lakes.

In 1903, he enrolled in the medical school in the University of Toronto, obtaining his degree in medical science in 1906. He continued to study comparative anatomy. In 1909 he received M.D. and M.A. degrees, and became an anatomy instructor at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio. His interest in anthropology was evoked there, and he spent many hours helping in the local museum of comparative anthropology and anatomy.

In 1913 he married his wife, Adena Nevit, who accompanied him on his trips. They had two children together, a son (b. 1921) and a daughter (b. 1926). Both were born in China.

In 1914, Black spent half a year working under neuroanatomist Grafton Elliot Smith, in Manchester, England. At the time, Smith was studying the "Piltdown man," which turned out to be a hoax, and was involved in the discussion of where were the origins of humanity—Asia or Africa. Black argued that China was the most suitable place for evolution to have started.

In 1917, during World War I Black joined Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps, where he treated injured returning Canadian soldiers. In 1919, he was discharged from the service, and went to Peking (now Beijing), China, in order to work at Peking Union Medical College.

At first he was professor of neurology and embryology, but soon he was promoted to head of the anatomy department in 1924. He planned on going on a search for human fossils in 1926, though the college encouraged him to concentrate on his teaching duties. With a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation, Black began his search around Zhoukoudian in China. During this time, many western scientists left China due to military unrest involving the National Revolutionary Army. Davidson Black and his family however decided to stay.

Black launched a large scale investigation at the site. He was the primary coordinator, and as such he appointed both Caucasian and Chinese scientists to work for him. One of the scientists, in the fall of 1927, discovered a hominid tooth, which Black thought belonged to a new human species, named by him Sinanthropus pekinensis. He put this tooth in a locket, which was placed around his neck. Later, he presented the tooth to the Rockefeller Foundation, which, however, demanded more specimens before further grants would be given.

During November 1928, a lower jaw and several teeth and skull fragments were unearthed, validating Black's discovery. Black presented this to the Foundation, which granted him $80,000. This grant continued the investigation and Black established the Cenozoic Research Laboratory.

Later in 1929 another excavation revealed a skull. Later, more specimens were found. Black traveled to Europe in 1930 where he found more accepting atmosphere than earlier. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1932 for his work.

In 1934, Black was hospitalized due to heart problems. He however continued to work. He died at his desk in Beijing, from a heart attack, working again alone late at night. He was 49 years of age.

Work

Davidson Black was convinced that the cradle of humanity was in Asia. He saw China's climate as being particularly suitable for the survival of early hominids. His claims were rooted in the earlier work of some German and Austrian paleontologists who found remains of early man in China. In 1926 Austrian paleontologist Otto Zdansky found two hominid teeth at Zhoukoutian's Dragon Bone Hill site, and in 1927 Swedish paleontologist Birger Böhlin found a nicely preserved left lower molar bone. Based on those findings, Black launched a large scale excavation at the site in Zhoukoutian, thirty miles from Beijing.

In 1929 Chinese paleontologist W. C. Pei, found a nearly complete skull embedded in the rocks of a cave. Black spent nearly four months trying to free the skull from the stone. After he managed to separate the bones, he reassembled the skull. Black believed that the brain capacity of the species placed it within the human range. Between 1929 and 1937, a total of 14 partial craniums, 11 lower jaws, a number of teeth, and some skeletal bones were found on the location of Zhoukoutian. Their age is estimated to be between 250,000 and 400,000 years old.

Black argued that the teeth and the bones belonged to the new hominid genus that he named Sinanthropus pekinensis, or "Chinese man of Peking." His claims met resistance in scientific circles, and he traveled around the world to convince his colleagues otherwise. Although the bones resembled closely the Java Man, found in 1891 by Eugene Dubois, Black claimed that Peking Man was a pre-human hominid.

Franz Weidenriech (1873-1948), a German anatomist, continued Black’s work. He studied the fossil materials and published his findings between 1936 and 1943. He also made a cast of the bones. During World War II, the original bones were lost, some believe sunk with the ship that was carrying them off the coast of China. Only the plaster imprints were left.

Criticism

Fellow researchers were skeptical of Black's classification of Sinanthropus pekinensis as a distinctive species and genus. Their objections lay in the fact that the claim of a new species was originally based on a single tooth. Later the species was categorized as a subspecies of Homo erectus.

Others, such as creationists, were and continue to be skeptical of Peking Man as a transitional species or an "Ape-Man," as non-human hominids have been commonly called. They claim it is a mix of human and ape fossils, or a deformed human.

Legacy

Davidson Black's research and discover of “Peking Man” greatly contributed to present knowledge of human evolution, especially regarding the human line that developed in Asia.

Unlike most Westerners of his era, Davidson Black tolerated and respected his Chinese co-workers. In return, he was well liked by many of them, who put flowers on his grave after his death. Also, unlike many Western excavators, Black believed artifacts discovered in China should be kept there.

Gigantopithecus blacki, the largest primate that ever lived, was named in Black’s honor.