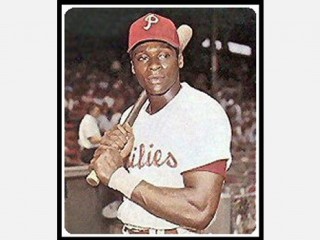

Dick Allen biography

Date of birth : 1942-03-08

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Wampum, Pennsylvania

Nationality : American

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2010-10-15

Credited as : Baseball player MLB, Oakland Athletics , Philadelphia Phillies

1 votes so far

For a solid decade during the 1960s and 1970s, Dick produced screaming line drives with his war-club of a bat—and he often had GMs waking up screaming due to his stubbornness and unpredictability. No one questions whether Dick was ahead of his time; he gave baseball an uncomfortable preview of the modern player. What his fans wonder, however, was how much this brooding ,insubordinate slugger could have accomplished had he found his comfort zone for more than just a season or two.

Richard Anthony Allen was born on March 8, 1942 in Wampum, Pennsylvania. He was one of eight kids—five brothers and three sisters. Dick’s mother Era was a devout, Bible-thumping Christian who took in wash and sewing to help make ends meet. His father Coy, who owned a trash-hauling business, liked to have a drink or two after work. The friction this caused between husband and wife was constant. By the late 1950s, Coy had left the family and moved 30 miles away.

Wampum was a small working-class town less than an hour away from Pittsburgh. It had begun as a trading post, hence its name. The Allens were one of the only African American families in Wampum, but Dick, or “Dickie” as his friends and family called him, remembers the town as being racially tolerant for that era.

From his father, Dick got his toughness and stubbornness. Coy had to deal with a lot of dogs on his route, and he never backed down from any of them. Legend had it that he could neutralize the meanest canines with his withering stare. Once, a Doberman came at Coy, and he knocked him out with a single punch.

Dick’s earliest passion wasn't for sports, but for horses instead. He also inherited this love from his dad. Dick had an entire stable of imaginary broomstick horses, each with its own name. His dream was to make enough money to own real horses—a dream he would one day realize.

The Allen boys—Coy Jr., Caesar, Hank, Ron and Dick—were known far and wide as special athletes. They would transform tiny Wampum High School into a regional sports power in the late 1950s.

The boys played football, basketball and baseball, but hoops was the family sport. All five brothers earned All-State honors, and in 1958, Hank, Dick and Ron made up three-fifths of the Wampum starting five. In 1960, Wampum rolled to the state championship. This was quite an accomplishment considering the entire student body was usually in the neighborhood of 500. The team’s coach, L. Butler Hennon, was nothing short of a miracle worker.

Of course, it helped to have Dick in the backcourt. He was firing jump shots and dunking when everyone else was still using hooks and set shots. One day, teammates measured Dick’s jumping ability; he touched a spot on the backboard 16 inches above the rim—not bad for a kid who stood a shade under six feet tall.

Dick, however, was not a showboater. In games, he laid the ball in and never jammed it. This changed after a summer league game in 1959. Legendary leaper and future NBA and ABA star Gus Johnson soared through the air and swatted Dick's layup on a breakaway. After that, Dick dunked everything. He was a monster. Years later, while in Philadelphia, he would often hit the gym with members of the 76ers during their shootarounds.

Few who saw Dick play doubted that he could have starred in the NBA. But baseball was where the money was back then. Older brother Hank and younger brother Ron both earned basketball scholarships, and then migrated to baseball. Hank would enjoy a brief career in the majors as a utility player, mostly for the Washington Senators, and Ron—who signed with the Philadelphia Phillies after Dick—would be a career minor leaguer, save for a few games with the St. Louis Cardinals in the early 1970s.

Dick first caught the baseball bug watching Negro league teams. Wampum had a fine field, and both the Pittsburgh Crawfords and Homestead Grays played there in the 1940s. Dick recalled seeing Josh Gibson and Cool Papa Bell play in his hometown as a little boy.

Among Dick’s major-league heroes was Pirates legend Roberto Clemente. He studied the Pittsburgh outfielder and admired the way he played the tricky right field wall at Forbes Field. Unlike Clemente, Dick was a gifted power hitter. While at Wampum High and in summer leagues, he sent drives to all fields that left teammates and opponents in slack-jawed awe.

Although Dick was recruited by a number of college basketball teams, it was clear by his senior year at Wampum that his future was in baseball. The scouts were all over him, and the bonus money being mentioned would be enough to buy a new house with separate bedrooms for every member of the family. Ultimately Dick signed with the Phillies. Their scout, John Ogden, had earned the trust of Dick’s mom. On one of his trips, he brought along Judy Johnson, the retired Negro League star. Impressed though she was, Era was no pushover. In addition to negotiating a $60,000 bonus for her son, she also talked Philadelphia into giving Hank a contract and hiring Coy as a scout.

Dick was now a member of an organization with a reputation for not embracing black players. The Phillies had scouted several high-caliber African American prospects in the 1940s and early 1950s, including Roy Campanella and Hank Aaron, but the team had not been aggressive in signing them. Based on who was ahead of Dick in the farm system, he would be the team’s first black star when he reached the majors. That pressure aside, he was irritated by his new name, Richie. The team had apparently decided on it without consulting him.

In his first stop for the Phillies, Dick reported to Elmira of the NY-Penn League. He played shortstop, though not particularly well, making 48 errors in only 88 gamesy. At the plate, he was far better, batting .281 in 320 at-bats with 37 extra-base hits.

Dick was promoted to Twin Falls of the Pioneer League the following year, in 1961. The Phillies moved him to second, and he acquitted himself well at the new position, leading the league in putouts and assists, and cutting his error total nearly in half. More important, he began to show the offensive prowess the team had paid for, socking 21 homers and driving in 94 runs with a .317 average. Dick’s baserunning also drew raves. He was quick and smart, rarely getting thrown out and constantly taking the extra base. Though still a teenager, Dick clearly understood that the role of a runner went beyond stealing; he did a masterful job of disrupting pitchers, which benefited his teammates at the plate.

The 1962 season found Dick in Williamsport of the Eastern League. Against stiffer competition, he continued to develop, leading the loop with 32 doubles and reaching double-digits in each of the extra-base hit categories. He eclipsed the century mark in RBIs for the first time with 109, and batted .329 while splitting his time between second base and the outfield.

Dick was running neck and neck with Jim Ray Hart for the Eastern League batting title but lost it on the season’s final day. Years later, the two stars were nearly traded for one another. The 1970s might have turned out differently for the San Francisco Giants and their fans with Dick forming a threesome with Willie McCovey and Bobby Bonds.

In the off-season, Dick married his fiancée, Barbara Moore, whom he had met in Williamsport. They would produce three children, Terry, Button and Dick Jr. When Dick received his 1963 contract, the newlywed asked Phillies GM John Quinn for a small, but well-deserved raise.

Dick had a good shot at making the big club out of spring training, but he was told by Quinn that if he did not withdraw his demand for more money, he would be shipped back to the bush leagues. Dick held his ground, and Quinn was true to his word. Some suspect the Phillies had an alternative agenda—their top farm team was located in the racial powder keg of Little Rock, Arkansas, and they wanted to send their best black player to that team.

Dick was a full-time outfielder with the Triple-A Arkansas Travelers in 1963. He was also the first African American athlete to play pro baseball in the state. To commemorate the occasion, Governor Orval Faubus threw out the first pitch at the home opener. Six years earlier, on another famous opening day, Faubus had blocked the entrance to Central High School to prevent black students from attending.

Dick was shocked at the reception awaiting him from Little Rock fans. On opening night, he saw a sign that said, "Nigger Go Home." Another said, "Don't Negro-ize Baseball." Dick thought that Jackie Robinson had already done that in the 1940s. It was time to think again. Dick was so nervous that he misjudged the first fly ball hit to him, and it landed over his head. He atoned for this miscue with a pair of doubles, including one hit so hard that it left many fans breathless. That knock keyed the game-winning rally.

Dick’s adjustment to LIttle Rock was made a bit easier by one familiar faced. His manager, Frank Lucchesi, had been the skipper in Williamsport.

Though profoundly unhappy, Dick did something with Arkansas that he would repeat throughout his career—channel his anger into a ferocious approach at the plate. Despite racial slurs, hate mail and death threats, he led the International League with 12 triples, 33 homers, and. 97 RBI. He coupled that production with a .289 batting average. Even more telling, Dick demonstrated a big-league approach at the plate—rifling fastballs to center and left, and staying with off-speed pitches by waiting and using his powerful wrists to line the ball all over the field.

At the end of the season, Arkansas fans held a vote and named Dick the team’s most popular player. Off the field, however, it was a different story. One night, he was out and bought a can of soda from a machine. On his way home, he was stopped by police, who accused him of stealing it.

On the positive side, Dick not only integrated the Travelers, in a way he integrated the ballpark, too. Prior to his arrival, the few African American fans who attended games were corralled in a small section of the right field bleachers. Because Dick played in left, black fans began migrating to that area. By the end of the season they were sitting all over the park. His arrival in Little Rock was a true culture-changing event.

Dick’s stellar season in Arkansas earned him a cup of coffee in Philadelphia at the end of the year. Phillies manager Gene Mauch was putting together a team of scrappy, talented players. As he looked toward 1964, he felt his outfield was set with Johnny Callison, Wes Covington and Tony Gonzalez. Where the team were thin was at the hot corner, so Mauch told Dick to grab a glove and get used to playing third. He saw limited action in the final weeks, garnering 24 at-bats in 10 appearances.

Though he had gone by the name “Dick” his entire life, the Philadelphia press continued to call him Richie, which he considered a little boy's name. Perhaps reporters were trying to create a link between Dick and the team’s last great star, Richie Ashburn, who had been traded to the Chicago Cubs and had since moved on to New York and become a Met. But Dick resented this slight throughout his days in Philly.

In the locker room, teammates marveled at Dick’s physique. He had a body built for baseball, with a wasp-thin waist, broad shoulders, quick wrists, massive forearms and sprinter’s legs. They also were in awe of what he carried to the plate—a 42-ounce bat, the biggest in the league and the heaviest since the days of Babe Ruth. The combination of power, torque and heavy lumber produced shots that rivaled those of another Philadelphia legend, Jimmie Foxx. Among the Hall of Famer’s tape-measure jobs as a Phillie was a ball that carried over the Coke sign in left field and left Connie Mack Stadium.

Dick used his war club to lead the NL with 325 total bases as a rookie in 1964. He used his legs to tie for the lead league in triples. And he also tied for first with 125 runs scored. The Phillies, meanwhile, seemed like a team of destiny. Dick batted .318 and was named Rookie of the Year for a club that won with pitching, defense, and timely hitting. The starting staff featured Jim Bunning and Chirs Short, two of the top hurlers of the 1960s. Young Rick Wise and Art Mahaffey filled out the rotation, while the bullpen was led by Jack Baldschun. Tony Taylor, Cookie Rojas, Ruben Amaro, Clay Dalyrimple and Frank Thomas were also valuable contributors.

Heading into his first full season as a major leaguer, Dick signed a $7,000 contract—$500 under the legal minimum. Someone in the front office caught the mistake and they paid the extra $500 toward the end of the season. Would Dick have been a free agent had the mistake gone uncorrected? It could have been an interesting test case.

The Phillies held a firm lead in September, but the team was on the brink of exhaustion with two weeks left. A 1–0 loss to the Cincinnati Reds on a steal of home by Chico Ruiz sent Philadelphia on a downward spiral. The team coughed up a 6.5 game lead with 12 to play, losing its final 10 in a row to finish a game behind the Cardinals in the pennant race. Mauch took much of the blame for overusing Bunning and Short down the stretch, but it was his clubhouse tirades and the constant tension in the dugout that was more likely the problem.

When Dick was named Rookie of the Year, he felt embarrassed and ashamed. He said years later that it felt wrong to accept an individual accolade after his team had played so hard and come up a game short.

With the city in mourning and the organization in a state of shock, the Phillies began undoing much of what was good about the club. With the 1965 season approaching, they brought in a couple of colorful baseball characters, Dick Stuart and Bo Belinsky, who did more harm than good. As so often happens, an overachieving team one year became a profound underachiever the next. The Phillies finished the year in the second division.

The ’65 campaign was a turning point in Dick’s baseball career. It started wonderfully. As the season neared its midpoint, he was ripping the baseball at close to a .350 batting average. Just days away from being named the NL’s All-Star third baseman, he got into a fight with Thomas. The veteran slugger, who was close to the end of the line, was known to have a mean sense of humor. One of his favorite gags was to offer a soul shake to black players, and then bend their thumbs backward. Dick called him “Lurch.”

The fight started because Thomas was picking on young Johnny Briggs, calling him “boy” on several occasions. Dick confronted Thomas during batting practice, and they came to blows. Dick hit Thomas with a left cross, and Thomas hit Dick on the shoulder with his bat. It took five players to pull them apart. One teammate, Ruben Amaro, took a punch trying to restrain Dick. A few hours later, Dick shook hands with Thomas, and things were on their way to calming down. But the damage was done. Their fight became the talk of the town after the Phillies announced that very night that Thomas had been released.

Although teammates supported Dick after the incident, the press painted him as the villain. From that point on, he was depicted in the Philadelphia papers as a bad teammate and a clubhouse cancer. The fans picked up on this theme and booed him mercilessly for the rest of the decade. Dick used this hatred to fuel his performance, and although he was miserable during his years in Philly, the numbers he put up in a lousy hitter’s park during the era of the pitcher were nothing short of phenomenal.

In 1965, Dick batted slumped a bit in the season’s second half to finish at .302. He belted 20 homers and played a much better third base. Plagued by throwing errors as a rookie, he began to find his comfort zone and committed 15 fewer miscues despite having Stuart (aka Dr. Strangeglove) on the receiving end of his tosses. He also led the NL in double plays by a third basemen. At the plate, Dick’s strikeout total soared. He fanned 150 times to set a new NL record and tied a major-league mark that year with five whiffs in a game.

The Phillies rebounded in 1966, finishing fourth in the NL. Their pitching was good again, and Dick continued the process of establishing himself as one of the most feared hitters in the game. The team might have given the pennant-winning Dodgers a run for their money but for a slow start. It coincided with an April shoulder injury suffered by Dick. The team lost 13 games in his absence, and he was unable to play third for more than a month after his return. He logged time in the outfield until he was able to throw.

Dick finished the year at .317 with 40 homers and 110 RBIs—his one and only triple-digit season for the otherwise anemic Phillies. He led the NL with a .632 slugging average and 75 extra-base hits. Philadelphia fans noted that his overall numbers compared very favorably to those of 1966 AL Triple Crown winner Frank Robinson.

The 1967 season was nearly Dick’s last. After an August rainout, he was at home with nothing to do and decided to work on the 1950 Ford in his driveway. When it wouldn’t start, he attempted to push it—and put his right hand through the headlamp. Dick’s mother made a tourniquet out of a towel and kept him from bleeding out as they rushed to the hospital. Doctors determined that he had severed two tendons and his ulnar nerve. After five hours of surgery—including the insertion of two pins—Dick’s hand was sewn back together, but his season was over. He was leading the league in on-base percentage at the time and finished as the NL OBP champ.

Dick rehabbed his hand by squeezing a rubber ball all winter. He arrived in spring training wearing a golf glove for extra support. Later that year, other major leaguers began wearing “batting gloves,” starting a trend that is now the rule rather than the exception. While Dick’s batting stroke was fine, he could not throw the ball. Mauch recognized this and moved him to left field. When Dick had to make throws, the shortstop would sprint toward him to shorten the distance.

Left field at Connie Mack Stadium was no treat. The fans first showered Dick with insults and racial epithets, and then progressed to pennies, bolts and batteries. He began wearing a batting helmet in the outfield and would continue to do so for the rest of his career. His teammates began calling him “crash”—short for Crash Helmet. After Dick retired, he named his autobiography Crash.

For Dick, the devils in the outfield convinced him it was time to get out of Philadelphia. He had already begun asking the team to trade him in 1967. Now he stepped up those efforts.

Dick would show up to the ballpark with beer on his breath and made sure the Mauch got a whiff. The manager responded by fining Dick almost on a daily basis. The team was spinning out of control and losing too often for the Philadelphia skipper to stay in the dugout. The team fired him before the All-Star break.

Despite his many distractions, Dick finished the 1968 season with 33 homers and 90 RBIs—in a year when an ERA of 3.00 was considered astronomical for a major league hurler. Like most every other hitter, Dick’s average dropped. He batted below .300 for the first time, but otherwise he remained among the most feared offensive forces in the game.

Among the distinguishing features of Dick’s plate appearances was the fury with which he swung at the ball. He had been playing angry for several years and was now quite good at it. Unlike most sluggers, he hit down on the ball. With his immense power, the result was line drives that could dent scoreboards 400 feet away. A typical "Dick Allen special" started just a few feet over the shortstop’s head and then began rising until it settled into the stands. Dick could launch drives to any part of the ballpark thanks to his quick wrists and strong forearms.

The 1969 season found Dick in another new position, stationed at first base. He felt immediately comfortable there. He had never found a groove throwing across the diamond and was not at his best in the outfield. Dick loved playing first, and it showed in his hitting. He had a good spring and was on pace for another terrific season.

Philadelphia±s new manager, Bob Skinner, got off on the right foot with Dick by promising that he would never punish him without hearing his side of the story. Skinner promptly broke that promise in June when he announced that he was suspending Dick for being late to a game. Dick found out on his way to Shea Stadium listening to his car radio. The start time of the game had been changed. and it had slipped his mind. At the time, Dick was batting over .300 and was among the league leaders in homers and RBIs.

Ironically, Dick had been the lone bright spot in a disastrous first half for the Phillies. Callison, Taylor, Short and slugger Deron Johnson were hurt, and Wise—who had become the team’s best pitcher—had been called up for military service.

During his suspension, Dick used his time away from the team to buy racehorses. He had built up a quality stable at his Bucks County farm and was starting to think he could make enough money in thoroughbred racing to walk away from the game. The Phillies expected Dick to return from his banishment a changed and more compliant man. When they began to realize that he might not come back, they panicked. GM Bob Carpenter finally lured him back with a promise that this season would be his last in Philadellphia—as long as Dick didn’t whisper a word of their deal to anyone. Dick completed the year with a .288 average, 32 homers and 89 RBIs—numbers nearly identical to 1968, except accomplished in a mere 115 games.

A few days after the end of the 1969 season, the Phillies dealt Dick to the Cardinals as part of a seven-player trade that brought Curt Flood and Tim McCarver to the Phillies. Flood was the key man, a Gold Glove center fielder with a .290 lifetime average. Only one problem—Flood refused to go to Philadelphia and decided to take on baseball’s reserve clause. For once, the controversy surrounding Dick was not of his own doing, yet he nevertheless found himself in the thick of the story.

When Dick arrived in St. Louis, he had grown accustomed to being called "Richie," even though his family, friends and teammates continued to call him Dick. In St. Louis, he became "Rich." Dick never figured out why this was, and it was one of his few complaints about playing in St. Louis. Manager Red Schoendienst greeted him in spring training and told him to go out and have fun. Cardinals fans were knowledgeable and appreciative. They gave Dick a standing ovation when he came to bat for the first time, bringing tears to his eyes. As far as racial problems, none existed in the St. Louis locker room. Bob Gibson was the clubhouse leader. End of discussion.

Dick felt comfortable enough to joke with the St. Louis press without fear of repercussions. At one point, he uttered the famousl line, “If horses won’t eat it, I won’t play on it,” referring to the Astroturf at Busch Stadium. In Philadelphia, Dick would have been excoriated for a remark like this. But Cardinals fans got it—and, more importantly, got him.

The only negative in St. Louis was that Dick had to relocate to third base after Mike Shannon was felled by a kidney ailment. In May, Schoendienst juggled his lineup again, moving Dick back across the diamond to first base. He was voted the All-Star starter over reigning MVP Willie McCovey, and by August he had reached the 30-homer, 100-RBI plateau. Among those circuit clouts were a couple of memorable blasts, including one that landed in the far reaches of the upper deck in left field.

The Cardinals were still in the hunt in the NL East when Dick tore his hamstring legging out a double. He did not return to the lineup until the end of the year—in time to slug a homer against the Phillies in the last game of the season.

During the interim, Dick got on the team’s bad side when he chose to recover in Philadelphia instead of staying in St. Louis. He had taken up residence in a hotel room after the trade and preferred his home in Philly. In October, Dick was informed that he had been traded to the Dodgers for Rookie of the Year Ted Sizemore. It was a steal for Los Anegles. Later, Dick wondered aloud what the Cards’ front office was smoking the night they made the deal.

St. Louis fans were wondering the same thing as they watched Dick smoke the ball in L.A. in 1971. The Dodgers desperately needed power for their anemic offense, and Dick obliged with 29 homers and 90 RBIs in a pitcher’s park. While he didn’t buy into the “bleeding Dodger Blue” culture, he was otherwise the leader of a transitional club that nearly edged the Giants in the NL West. After the season, Dick got the heave-ho again, this time heading for Chicago in exchange for Tommy John.

The 1972 White Sox reminded Dick of the 1964 Phillies. They had a smattering of talent and tons of heart. Their manager, Chuck Tanner, was the perfect skipper for Dick. Tanner had long maintained that he had 25 different sets of rules for 25 guys, so the "Dick Allen Rules"—whatever they would be—wouldn’t rankle anyone in the Chicago organization. More important, Tanner had grown up a few miles from Dick and his brothers and knew all about their remarkable talent and deep desire to win.

The Windy City media seemed to be on Dick’s side, too. During his introductory press conference, a reporter noted that he had been Richie and Rich in the past. What name should they use? Dick was bowled over. He asked them to use the name his mother gave him, and the newspapers complied.

Chicago’s stars included Bill Melton, Walt Williams and Carlos May. When Melton went down early with a back injury, Dick was left unprotected in the lineup. It hardly seemed to matter. Playing happy and healthy baseball from start to finish, he produced perhaps the greatest offensive season in team history.

Among his memorable moments that year was a pinch-hitting appearance in the second game of a doubleheader against the Yankees. Dick had played in the first game, so Tanner gave him a breather in the second half of the twinbill. New York led 4–2 in the ninth inning when Dick came to bat and drilled a three-run homer off of the unusually untouchable Sparky Lyle.

On the last day of July, Dick showed he still had good wheels when he motored around the bases for a pair of inside-the-park home runs against the Minnesota Twins. He was the first player in baseball’s modern era to accomplish this feat.

Another memorable shot that season almost decapitated Harry Caray, who was broadcasting the game for the White Sox from the centerfield bleachers. Dick found Caray to be irritating and drove home this point in unique style by lashing a patented rocket over second base and into the stands. Caray hesitated for an instant, not believing a ball that started so low would be a threat more than 400 feet from home plate. By the time he realized he was in harm's way, he spilled beer all over himself scrambling out of range.

Dick also contributed to the Chicago’s season with his mind. He spent a lot of time standing next to Tanner discussing strategy and sharing his on-field observations. The manager later credited much of the team’s success to Dick’s contributions in the dugout. The White Sox kept the heat on the Oakland A’s all season long, finishing a close second down the stretch.

Dick found the AL very much to his liking. In the NL, he could expect at least one close shave a game—more when a Gibson or Drysdale or Marichal was on the mound. In the Junior Circuit, pitchers tended to nibble with off-speed stuff and rarely came inside. Dick just waited for a good fastball and then went to work.

His final numbers reflected his comfort level. Playing once again in a pitcher’s park, he led the league with 37 homers, 113 RBIs, a .603 slugging average, .420 on-base percentage and 99 walks. Teammates are nearly unanimous in the observation that Dick’s numbers in ’72 only hinted at the year he had. Time and again, when the White Sox needed a hit, Dick would come through. He was as close to automatic that year as a batter could be.

Dick was a no-brainer pick for AL MVP. More important, he revived the passion of fans on the South Side, thus eliminating conjecture that the club might pull up stakes and relocate to Seattle or the west coast of Florida.

After the season, the White Sox gave Dick a new contract for $250,000 a year, up from $100,000. His top salary with the Phillies had been $85,000. Another benefit of Dick’s MVP campaign was that he was able to convince the White Sox to add his brother Hank to the roster. Hank, who was 85 games short of qualifying for a pension, proved to be a valuable bench player during Chicago’s 1972 run.

Fate was never particularly kind to Dick. The 1973 season was a particularly painful example. In a June game against the A’s, he collided with massive Mike Epstein during a play on the first base line. Dick broke his leg and ended up missing 90 games. He was batting over .300 at the time and was on pace for a repeat of his numbers from the year before.

The White Sox weren’t the same when Dick returned to the field in 1974. Ron Santo had come across town from the Cubs for his final major league season and tried to install himself as the team’s leader. The other players, meanwhile, still considered Dick their go-to guy. This created tremendous friction between the two stars, and Dick berated Santo for not working with the team’s younger players to make them better. Tanner told both players than only one guy was running the White Sox—Tanner.

Dick was fed up. Baseball wasn’t fun anymore. He gathered his teammates in the clubhouse on September 14th and announced his retirement. Despite not playing the rest of the year, he still led the AL with 32 homers and a .563 slugging average. It was the first time a retired player ever led a league in a major offensive category. Fueling Dick’s departure was an offer from a Japanese baseball team for $2 million a season—many times more than the top players were making at that time. Tired of being a baseball gypsy, he still toyed with the idea of heading overseas but in the end decided against it.

Like many retired players, Dick found that he didn’t fit in around the house anymore. Barbara and the kids had gotten used to living without him, and his presence began to cause problems in the marriage. Eventually, they would get divorced.

Dick’s retirement was soon interrupted by a stream of visitors from the Phillies. Richie Ashburn, Robin Roberts, Mike Schmidt and others tried to convince him that things had changed in Philadelphia. The team was building a winner, and they needed his big bat and veteran presence.

Commissioner Bowie Kuhn caught wind of these visits and—because Dick had never turned in his retirement paperwork—launched a tampering investigation. Dick was technically the property of the Atlanta Braves, who had acquired his contract from the White Sox. Dick relented and agreed to join the Phillies. Philadelphia acquired his contract after he told the Braves in so many words that he would rather sit at home than play in the South (even the New South) again.

Philadelphia manager Danny Ozark pressed Dick into service right away. He asked for more time to find his groove, but the press was pushing the team to get Dick on the field. He ended up playing 113 games at first base, driving in 62 runs despite a .233 average. His main contribution to the Phillies that year was working with their two sluggers, Schmidt and Greg Luzinski. Dick taught Schmidt to hit down on the ball and told him he couldn’t take the outs he made so personally. Luzinski was a low ball hitter who constantly got himself out chasing high pitches. Dick taught the Bull how to be more of a zone hitter. He responded with a monster year, racking up 120 RBIs. The Bull’s increased production actually affected Dick’s performance. Luzinski was a horrible base runner. When he was on base, Dick could not do any situational hitting.

The Phillies finished second in 1975 but were favored to win the NL East the following year. Dick came back, upped his average to .268 and boosted his slugging average by nearly 100 points to .583. Philadelphia opened a big lead over the Pirates, who challenged them in September only to fall short.

The last month of the 1976 campaign was a tumultuous one. The Phillies should have been preparing for their first postseason since 1950, but instead simmering tensions were boiling to the top. Dick felt there was a quota system in place—how else could one explain the lack of at-bats for Ollie Brown and Bobby Tolan? Meanwhile, Larry Bowa and Tug McGraw were driving everyone crazy with their clubhouse antics and media-hogging. At one point, Bowa said he missed the team’s old first baseman, Willie Montanez, implying that Dick wasn’t scooping balls out of the dirt the way his predecessor had. Dick called Bowa out and told him to throw the balls to his glove—end of problem.

Things went from bad to worse when the Phillies said they planned to leave veteran Tony Taylor of the postseason roster. Taylor had taken Dick under his wing a dozen years earlier and was coming to the end of a long and distinguished career with the Phillies. Dick was outraged. He threatened to quit if the Phillies went through with their plan. The team kept Taylor on board, but the damage was done. The Phillies were swept by the Reds in the NLCS.

One of the three losses was pinned on Dick, who appeared to make a half-hearted stab at a line drive by Ton Perez. The winning run scored on the play. Everyone on the field knew the truth—a pickoff play was on, and Dick was moving toward the bag when the pitch crossed the plate. When Perez flicked the ball to right, Dick had to reverse directions and couldn’t get off the ground in time to stab the ball. The official scorer ruled it an error and stuck to his guns, even when several Reds explained what had happened. Once again, Dick was persona non grata in the City of Brotherly Love.

Dick was not invited back by the Phillies in 1977, but he still felt there was some good baseball in his body. When fellow renegade Charlie Finley offered him a job in Oakland, he grabbed it. Dick quickly realized his mistake. Finley would say one thing and do another, and according to Dick, he broke several promises he made when working out the contract. After 54 games for the A’s, Dick said goodbye to baseball for good.

Dick’s final numbers in the big leagues were 351 home runs, 1,119 RBIs, 1,009 runs and a .292 average. His career slugging percentage was .534—he was among the top five in the league seven times—and his on-base percentage was .378. Dick played 807 games at first base, 652 at third and 256 as a left fielder. He also logged a handful of appearances at second, short and in center field. Dick was named to seven All-Star teams during his 15-year career.

Dick’s retirement years did not go as planned. He had imagined himself as a horseracing entrepreneur, but it proved more challenging than expected, and Barbara was unhappy with her role in the business. Falling behind in his bills, he let his insurance lapse, and in 1979 a freak electrical fire burned his house down. Soon Dick and Barbara were divorced. She received an extremely generous judgment, which included virtually all of his remaining assets, as well as his baseball pension.

For many years Dick claimed he had no interest in coaching; he would never put on a uniform again if he couldn't play. But his fertile baseball mind and desperate circumstances eventually led him back to the game he loved. He worked with the White Sox and later the Phillies as a hitting instructor.

In the years following his retirement, Dick’s reputation as a guy who upset team chemistry and used racism as a weapon did not change all that much. His 1987 autobiography Crash did little to soften this image, although most of his former managers claimed he was not the disruptive presence he was made out to be. Nevertheless, Dick was remembered by historians such as Bill James as a player who did as much to hurt his teams as help them. That being said, James rated him 15th among history’s greatest first basemen—ahead of no fewer than 10 Hall of Famers.

In 1997, Scott Rolen became the first Phillie since Dick to be named Rookie of the Year. When asked to compare himself with Rolen, Dick said that they were both team-first players and lauded Rolen for his sparkling defense. He joked that in his days as a Phillie third sacker, his nickname was “E–5.”

In 2005, Dick was honored by the Philadelphia Sportswriters Association with its Living Legend Award. The irony was not lost on his fans. But a lot had changed since his playing days. When Ryan Howard became the fourth Phillie to win Rookie of the Year, Dick was among those on hand to congratulate him. He had first worked with the young slugger as a coach during spring training four years earlier. Older and mellower, Dick said that Howard reminded him of what it felt like to be a young star with his future ahead of him.