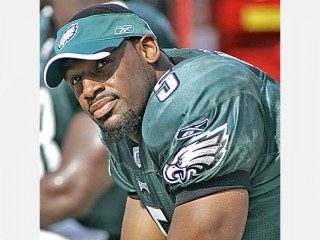

Donovan McNabb biography

Date of birth : 1976-11-25

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Chicago, Illinois, USA

Nationality : American

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2010-08-10

Credited as : Football player NFL, currently plays for the Philadelphia Eagles, Super Bowl

1 votes so far

Donovan Jamal McNabb was born on November 25, 1976, in Chicago, Illinois. His parents, Sam and Wilma, already had a four-year-old son, Sean. Donovan was their second and last child. The McNabbs lived on Chicago's notorious South Side. Sam, who worked as an electrical engineer for the power company, preached the values of modesty and hard work. He instructed his boys to always do the right thing, strive to overcome the obstacles they encountered, and remain focused on their goals. Wilma was more of a sounding board for Donovan and Sean. A full-time nurse, she spent countless hours talking with her children and helping them work through whatever problems they faced.

Tired of making the best of a bad situation, Sam and Wilma started looking for a safer place to live. As soon as they could afford it, the McNabbs moved some 30 minutes south, to the suburb of Dolton. Donovan was eight when they settled into their new house. The neighborhood welcome wagon was slow in reaching the McNabbs, the first black family on the block. In fact, a welcoming committee of a different sort visited their home first—leaving shattered windows and spray-painted obscenities as a calling card.

Once the neighbors got to know the McNabbs, the fear factor dissipated and life in Dolton returned to something like normal. Donovan, who had a special talent for making friends, had much to do with this. Smart, funny, and extremely personable, he was the life of the party. He could never get enough attention, and in school he became the class clown.

This may have endeared him to the other kids, but it did not sit well with his coaches. Name the game and he always seemed to be goofing around. Despite his obvious ability, the guys in charge did not think Donovan was serious about sports. They were much more enthusiastic about Sean. Donovan's big brother was strong and well coordinated, and instantly became a star in football and basketball. Donovan idolized Sean. He hung out at his practices, watched all his games, and even served as manager of one of his hoops teams.

When Donovan was old enough for tackle football, he asked his parents if he could join the local league in Dolton. Wilma was against the idea. Donovan was not as large and well-muscled as Sean had been at the same age. She was afraid he'd get killed. The team's coach paid her a visit and assured her that her baby was big enough to don the pads. Donovan took his first snaps under center in the seventh grade. He never played another offensive position.

Donovan entered Chicago's Mount Carmel High School—an all-boys Catholic school—in the fall of 1990. Mt. Carmel first established a winning sports tradition in the 1940s and 50s, when Notre Dame football coach Frank Leahy began mining the school's roster to replenish his nationally ranked teams at Notre Dame. When the legendary Fighting Irish coach retired after the 1953 campaign, he was succeeded by Terry Brennan, Mt. Carmel class of 1945. The school's basketball team was also nationally recognized and a perennial contender for city and state titles.

Donovan had grown into his body by ninth grade, and like Sean was a standout in both football and basketball. He was surrounded by great talent during his years at Mt. Carmel, including basketball star Antoine Walker. Donovan played point guard and was an excellent defender. As a senior he led Mt. Carmel to a 25-4 record and was an all-area selection by the Chicago Sun-Times.

Donovan made an even bigger impression on the gridiron. A strong-armed quarterback with the open-field moves of a halfback, he also possessed the intangibles coaches look for in a leader. As a sophomore, he ran the scout-team offense. By game day, the defensive starters could hardly wait to play—their regular opponents were often easier to contain than Donovan. No one was happier than Simeon Rice, Mt. Carmel's All-America linebacker and defensive end. He got so frustrated chasing Donovan around the practice field that he sometimes buried him after the whistle had blown.

Mt. Carmel coach Frank Lenti made Donovan his starting quarterback in the fall of 1992. Lenti favored a pro-option attack that required a quick-footed, quick-minded signal caller to make the offense go. Donovan, a junior, patterned his game after Charlie Ward, who was just coming into his own at Florida State. Mt. Carmel averaged 35.3 points a game during Donovan's first year at the helm, the second highest mark in the school history.

His scintillating junior season sparked an intense recruiting war among several of the nation's college football powers. While schools like Florida and Florida State ignored him because he was an option quarterback, those that relied heavily on the ground game coveted him. Nebraska figured to have the inside track. The Cornhuskers, in the midst of a dominant run under coach Tom Osborne, featured an offense perfectly suited to Donovan's talents.

With college recruiters watching his every move, Donovan went out and turned in a brilliant senior season for Mt. Carmel. Though it appeared his ticket to Nebraska was pre-punched, he surprised everyone by announcing that he had accepted a scholarship to Syracuse University.

The choice actually made a lot of sense. At Nebraska, he might sit behind quarterback Tommie Frazier for two years, while Syracuse, despite coming off two bowl appearances, needed a quarterback. Plus, coach Paul Pasqualoni agreed to let Donovan play for Jim Boeheim's basketball team. The kicker in the deal was the school's great communications department. Donovan one day hoped to have a sportscasting career, and Syracuse had produced booth men the likes of Bob Costas, Marv Albert, and Sean McDonough.

ON THE RISE

After arriving on the Syracuse campus in the summer of 1994, Donovan was redshirted by Pasqualoni. With the graduation of quarterback Marvin Graves, the coach had to rebuild his offense. He felt his prize freshman would benefit more from a year of watching and learning than feeding him immediately to the wolves of the Big East. Pasqualoni hoped Donovan could become a four-year starter, and wisely chose not to rush him along.

When the 1995 season opened, the Orangemen were on the rise. Although they did not figure to challenge for supremacy in the Big East, they had an outside shot at a bowl bid—if one of Pasqualoni's three young passers produced. Donovan went into camp vying for the starting job with Kevin Johnson and Keith Downing. The three-way battle was so tight that Pasqualoni did not decide on his starter until just hours before kickoff of Syracuse's opener in North Carolina. Donovan got the call and, not surprisingly, he struggled through the first three quarters. In the final period, however, everything fell into place, as he engineered three scoring drives for a 20-9 victory.

Syracuse dropped its next game, to East Carolina, then reeled off eight wins in a row. Donovan was sensational. He picked up the intricacies of Pasqualoni's offense and made it his own. With their quarterback in the comfort zone, Donovan's teammates were free to do what they did best. Marvin Harrison, on the receiving end of more than 50 McNabb passes, topped the 1,000-yard mark and transformed himself into a first-round NFL pick. With defenses keyed up to stop Donovan's running game, halfback Malcolm Thomas had a great year, too.

Donovan was a unanimous selection as the Big East Rookie of the Year. He finished the campaign with 526 yards rushing, 2,300 yards and 19 TDs passing, and a quarterback rating of 162.3, which obliterated Kerwin Bell's NCAA freshman record that had stood for more than a decade. The only down note of the year came in the final regular season game, against Miami. Syracuse needed a win to grab the conference title. Donovan started like a house afire, building a 24-14 first-half lead. But the Orangemen's defense, shaky all season, gave way in the second half. Miami got three touchdowns and kept Donovan off the board for a 35-24 win. Syracuse's 9-2 record was still good enough for a berth in the Gator Bowl against Clemson. Donovan went wild against the Tigers, passing for 329 yards and three scores and running for another in a 41-0 blowout.

Donovan jumped right from the gridiron to the hardwood, where he was used sparingly by Boeheim. He led the cheers from the bench, however, in what turned out to be a great season for Syracuse. When forward John Wallace heated up in March, the Orangemen advanced to the NCAA Final against Kentucky and Donovan's old high school teammate, Antoine Walker. The Wildcats prevailed, 76-67, but it was still a marvelous run for Syracuse.

Donovan took the field for his second football season in 1996 knowing he had to top his record-setting freshman campaign. The Orangemen were also expected to challenge Miami again for the conference title. Donovan was magnificent again, winning Big East Player of the Year honors. The offense survived the loss of Harrison to the pros and, after a pair of mistake-filled losses to UNC and Minnesota, played strong, smart football the rest of the way. The defense also improved, thanks to the play of hard-hitting ballhawks Kevin Abrams and Donovan Darius.

Syracuse won eight straight after its early season stumbles, and Donovan figured pominently in every victory. He did it with his arm (328 passing yards in a 45-17 rout of Boston College) and with his legs (125 rushing yards against stingy Virginia Tech). Once again, the Orangemen faced Miami in the season finale with first place on the line. And once again, the Hurricanes found a way to beat them. This time the Floridians built up a big first-half lead and then nursed it home for a 38-31 victory. The loss meant Syracuse had to share the Big East crown with Miami. A month later Donovan and his teammates gained a measure of redemption by handling Houston in the Liberty Bowl, 30-17. The team finished at 9-3 for the second year in a row.

After another season on the bench with the basketball team, Donovan was happy to return to football. There were holes to plug here and there, but the offense was not among Pasqualoni worries. In fact, Donovan's emergence as a superstar enabled the coach to shift backup QB Kevin Johnson to wideout, where he used his speed and smarts to become an outstanding receiver. The defense, which was brilliant in 1996, was dealing with the loss of seven starters. The talent was there to replace these players, but it would take time for them to jell. In the meantime, the Orangemen had to avoid the September woes that had plagued them in the past.

Everything clicked in the opener, a 34-0 whitewash of Wisconsin in the Kickoff Classic. But the Orangemen followed that victory with three straight defeats. They lost close ones to NC State and Oklahoma, then got embarrassed by Virginia Tech. With the season on the verge of collapse, Donovan rallied his troops and led Syracuse to eight straight wins. In their annual war with Miami, the Orangemen trounced the Hurricanes 33-13 to claim the Big East title outright.

A loss to Kansas State in the Fiesta Bowl prevented the team from claiming a ninth consecutive victory. Donovan was overwhelmed by the Wildcats' swarming defense—a rare occurrence in 1997. Indeed, he set personal highs during the regular season with 2,488 yards passing and 20 touchdowns, while his 2,892 yards in total offense established a new school record. For the second year in a row Donovan was named Big East Player of the Year.

Donovan felt the team could contend for the national title in 1998 if everything broke right. With that goal in mind, he bid farewell to basketball and began logging long hours lifting weights and studying film. He also began working to correct minor flaws that had cropped up in his passing technique. This included curing his occasional wildness on throws to his right and perfecting his footwork on five- and seven-step drops.

When Syracuse fans got a load of the new and improved Donovan, they believed they might have a Heisman-caliber quarterback on their hands. It hardly mattered that writers considered him a notch below the likes of UCLA's Cade McNown, Central Florida's Daunte Culpepper, and Kentucky's Tim Couch. Donovan's teammates would gladly have gone into battle with him over those guys. That was fitting, for the first two dates on the 1998 schedule looked like wars. The opener, at home against Tennessee, and game two, on the road at Michigan, would determine whether the Orangemen had a shot at a national championship.

The Tennessee game was a classic. With Donovan piling up 300 yards through the air, it went right down to the wire, but the Volunteers won 34-33. Coach Pasqualoni only had four returning starters on defense, and the Vols exploited the lack of cohesion and experience. Syracuse bounced back against Michigan, as Donovan had a hand in four of the team's five TD's in a 38-28 victory. Unfortunately, the season took a surprising turn for the worse over the next few weeks with losses to NC State and West Virginia. The pair of defeats ended any chance of a national title for the Orangemen, but the Big East title was still within their grasp. They secured it with a 66-13 victory over Miami. Syracuse had less luck in the Orange Bowl, losing 31-10 to Steve Spurrier's Florida Gators.

Syracuse's up-and-down season denied Donovan a serious shot at the Heisman Trophy, which went to Ricky Williams. Several stunning performances, however, caught the eye of NFL scouts. In a 63-21 thrashing of Cincinnati, Donovan tied a school-record with four TD tosses. He then sparked a furious 28-26 comeback victory over Virginia Tech, throwing two second-half touchdowns, including a 13-yarder to tight end Stephen Brominski on the last play of the game. He also ran for three touchdowns and threw for two more in the Miami game. For the season, he completed 157 of 251 passes for 2,134 yards and 22 scores. He also rushed for 438 yards and eight TDs. Donovan was named Big East Player of the Year for an unprecedented third year in a row.

MAKING HIS MARK

Heading into the 1999 NFL Draft, Donovan was part of a class of quarterbacks being compared by some to the 1983 collegiate crop that produced John Elway, Dan Marino and several other impact passers. What talent evaluators loved about Donovan was his strong arm and superior athletic ability. The term used most often to describe him was “playmaker.” Some saw a little bit of Brett Favre in him.

Donovan's detractors claimed he was not technically sound, and wondered whether he could handle the complexities of the pro game. This was due in part to the fact that he had been an option quarterback at Syracuse, but it also smacked of a prejudice among the unenlightened in the NFL against black quarterbacks. In media interviews, Donovan tried to avoid this issue altogether. Cleveland, Philadelphia, and Cincinnati—the teams set to pick 1-2-3 in the draft—all worked him out in private sessions. All three needed a quarterback, but with Ricky Williams in the draft-day mix, none would say which way they were leaning.

The Browns opened the action by making Tim Coach the #1 pick. Next up were the Eagles. The boisterous Philly fans who made the trip to New York's Felt Forum didn't hide their feelings: Williams was their man. In fact, a resolution had been presented to the Philadelphia City Council urging the selection of the Heisman winner. Even mayor Ed Rendell got in on the act, appearing on a local radio sports show to tell listeners to voice their support of the Williams pick.

Luckily, Andy Reid, who left Green Bay to coach the Eagles, was a better football man than Rendell. A disciple of Bill Walsh's West Coast offense, Reid had coached Favre and Steve Young and knew a special player when he saw one. Donovan reminded him of both signal-callers—not only physically, but also in terms of demeanor. He was a first-rate leader who knew how to get the most out of his teammates. When Reid and quarterbacks coach Brad Childress grilled Donovan before the draft, he gave them all the answers they were looking for.

When NFL commissioner Paul Tagliabue announced the Eagles' pick of Donovan in New York, boos could be heard all the back in the City of Brotherly Love. The 23 year old laughed off the harsh reaction. At a reception in his honor at the Ritz-Carlton in Philadelphia, Donovan won over fans with his easy charm and playful sense of humor. Mayor Rendell, a politician to the very end, was on hand to present the rookie with a gift from the people of his city. Without missing a beat, Donovan gave the mayor a jersey with his #5 on the back…end Ricky Williams's #34 on the front.

The Eagles were coming off a disastrous 3-13 campaign. Ray Rhodes, once the league's most promising new coach, had left the franchise in a shambles. The 1998 club had bottomed out, finishing dead-last in total offense, passing, and scoring. The picture wasn't much prettier on defense. Reid aimed to remedy this situation by introducing new systems and strategies instead of new players. As far as he was concerned, Philadelphia had plenty of talent. On defense, Hugh Douglas, Jeremiah Trotter, Bobby Taylor and Troy Vincent gave coordinator Jim Johnson a good nucleus to work with. On the other side of the ball, Duce Staley was a legitimate 1,000-yard rusher behind an improving line. The only major changes came in the passing game. Receivers Charles Johnson and Torrance Small were added to the roster, while QB Doug Pederson—formerly the backup to Favre—made the trip with Reid from Green Bay and was slotted in at starter.

Although the Eagles looked better early in the 1999 campaign, they had just two wins after their first nine games. With Pederson unable to do the job at quarterback, Reid named Donovan his starter for a November contest against the Redskins. His numbers for the game were modest, but anyone with eyes could see how dramatically different the team's tempo was with him under center. The Eagles defeated Washington, 35-28, making Donovan the first Eagles rookie to win his first NFL start since Mike Boryla in 1971.

Donovan started five more games down the stretch, notching victories over the Patriots and Rams, who were on their way to a Super Bowl win. He was at his most dangerous when flushed out of the pocket, turning plays upfield when other rookies might have thrown stupid passes or been tackled for big losses. Donovan ended his rookie campaign with 948 yards passing and eight touchdowns, and added another 313 yards rushing on 6.7 yards per carry. Though the Eagles again limped home with the NFL's worst offense, there was reason for optimism.

Philadelphia added youth and muscle to the roster in the offseason. The Eagles grabbed Corey Simon, the cat-quick defensive lineman from Florida State, with the sixth pick in the first round, then gave Donovan another outside target by tabbing receiver Todd Pinkston in the second round. The team also signed right tackle John Runyan from the AFC champion Titans to shore up the offensive line.

The Eagles experienced a remarkable turnaround in 2000, going 11-5 and posting their first postseason victory since 1995. The defense never stopped attacking. Douglas and Simon combined for 24.5 sacks, while Vincent and Taylor led one of the league's best secondaries. In the playoffs, the Eagles manhandled the Buccaneers 21-3. Though the team fell a week later to the Super Bowl-bound Giants—who beat them a total of three times during the year—all of Philadelphia celebrated a marvelous year. As for Donovan, he was the town's new superhero. When Staley went down with a knee injury in October, fans girded themselves for another soul-crushing season. Left naked without a running game, the Eagle offense turned to Donovan, who led the club in rushing with 629 yards and six scores. He also found time to throw the ball, amassing 3,365 yards and 21 more touchdowns. In all, Donovan accounted for nearly 75 percent of Philadelphia's yards from scrimmage.

Donovan's highlight reel included his first 300-yard passing game, in a 38-10 drubbing of Atlanta, and a 390-yard, 4-TD effort against the Browns. No game, however, demonstrated Donovan's value to his team more than his performance at Washington in a 23-20 November victory. When the Redskins put the clamps on the Eagle passing attack, he ran the ball down their throats. Donovan finished the contest with 125 yards on the ground—the highest total by an NFL quarterback since Bobby Douglas in 1972. With the score tied late in the fourth quarter, Donovan broke loose for a 54-yard gain that set up the winning field goal. The man who two years earlier practically had to beg for the attention of Heisman voters was now a legitimate pick for NFL MVP. In fact, he came in second in the voting to Marshall Faulk.

Having a one-man wrecking crew like Donovan is fun, but a good coach knows the smart play is to surround a special player with the kind of talent that will really let him spread his wings. Thus in the off-season, Reid set out to upgrade his receiving corps. He signed James Thrash of the Redskins, drafted Freddie Mitchell of UCLA, and planned a bigger role for tight end Chad Lewis. Donovan was also looking for ways to improve. To handle the speed of the pro game more effectively, he felt he needed to increase his peripheral vision. Under the guidance of personal trainers, he used specially designed glasses during workouts that forced him to see better side-to-side.

No longer the NFC East doormat, Philadelphia was the odds-on favorite to win the division in 2001. The Eagles dropped their opener to the Rams, 20-17, then won two of their next three. Their fifth game was a Monday Night matchup with the hated Giants. The New Yorkers outplayed Philly all evening, but the Eagle defense kept things close. In a stunning fourth-quarter comeback, Donovan drilled an 18-yard TD pass to Thrash after the two-minute warning to win the game. From there Philadelphia went on a Syracuse-like roll. Donovan was terrific, running the Eagle winning streak to eight straight and delivering the franchise's first division crown since 1988. On the last weekend of the regular season, Donovan nailed the Giants with another fourth-quarter comeback, 24-21. For the year, he eclipsed the 3,000-yard mark, threw for 25 touchdowns, and rushed for another 482 yards and two more scores.

For the second time in two years, Donovan blew the doors off Tampa Bay in the opening round of the playoffs. The 31-9 win was textbook postseason football. Donovan stuck to a conservative gameplan and simply ground the Bucs into the turf. The following week, in Chicago, Reid told Donovan to go out and have fun. He knew his quarterback would have a big day with his family and friends in the stands. Donovan put points on the board on Philadelphia's first two drives against the vaunted Bears defense, then added a touchdown at the end of the first half to swing momentum the Eagles' way. Philly extended its lead in the second half and cruised to a 33-10 win. Donovan was sensational, completing 26 of 40 passes and tossing a pair of touchdowns.

As they had the season before, the Eagles met a team of destiny in the postseason. It was the Rams this time, with Kurt Warner and Marshall Faulk and Isaac Bruce leading the way. Donovan managed to put points on the board, but the St. Louis offense was just too much, and the Eagles lost, 29-24. Philadelphia fans ached at the thought of how close they had come to the Super Bowl, but then again, who in the world would have believed they would reach the NFC championship game as quickly as they did? Actually, Donovan believed. From his first taste of the playoffs, he knew he had the makings of a championship quarterback. Everything just felt right when he was on the field in a big game.

Donovan and the Eagles entered the 2002 campaign intent on going to the Super Bowl. The team had a slightly different appearance, particularly on defense. When linebacker Jeremiah Trotter bolted for Washington, Philadelphia replaced him in the middle with Barry Gardner and added free agent Shawn Barber. The offense, meanwhile, remained virtually the same. With Donovan at the helm, Staley in the backfield, and Thrash and Pinkston leading an underrated group of receivers, Reid felt he had more than enough scoring threats.

From the opening game of the regular season, Donovan had the look of an MVP. Through the first month of the year, he had more than 1,000 yards passing and nine scoring tosses against just three interceptions. By the end of October, the Eagles were 5-2, and Donovan continued to show his versatility. He topped the 100-yard rushing mark against the Jaguars and Giants, and also engineered an impressive victory over the Buccaneers.

The Eagles remained the cream of the crop in the NFC as they moved through November. Then disaster struck. During a 38-14 rout of the Cardinals, Donovan hurt his ankle. At first the injury didn't seem serious. In fact, he played the entire game, completing 20 of 25 passes for four TDs. But when x-rays revealed a fracture, Donovan was forced to the bench.

Amazingly, Philadelphia flourished without their leader. Thanks to a masterful coaching job by Reid, the Eagles took their next five before dropping their final contest against the Giants. When the Packers lost the following day, however, the club seized homefield advantage in the playoffs by virtue of their 13-3 record. With the temperatures dipping in Philly and the swan song for Veterans Stadium soon to be performed, the Eagles felt they had an overwhelming edge in the postseason.

The only question was whether Donovan would recover in time for the playoffs. Working in Philadelphia's favor was the team's first-round bye, which provided him with an extra week of rest. Though rookie A.J. Feeley had done a superb job running the team in his absence, the Eagles were a more confident and explosive club with Donovan calling the signals.

That was apparent in Philadelphia's first playoff contest against the Falcons. Though Donovan was not completely healthy, he gave his team a spark by simply stepping on the field. Early in the contest, he broke from the pocket and sprinted for a 19-yard gain. While that was his only substantial run of the evening, it served a valuable purpose, keeping the aggressive Atlanta defense on its heels. With the Eagle defense clamping down on Michael Vick, Donovan showed his postseason poise by managing the game and taking advantage of big-play opportunities when they presented themselves. Philly won 20-6, and Donovan's performance (20 of 30, 247 yards and a touchdown) was awesome in its simplicity.

The Eagles hoped to duplicate that effort a week later in the NFC Championship Game against Tampa Bay. The Buccaneers, however, were ready for Philadelphia's gameplan. Dropping back in a suffocating zone defense, the Bucs confused Donovan all game long. With his ankle still weakened, he was unable to keep Tampa Bay's speedy front seven honest with the run threat. The Buccaneers blew the contest open in the second half and cruised to an easy 27-10 victory. Of slight consolation for the Eagles was the fact that the Bucs dismantled the Raiders, 48-21, in the Super Bowl.

After their second trip to the NFC Championship Game—and their second lost—the Eagles felt that 2003 would be their year. They added several key free agents, including fullback Jon Ritchie and linebacker Nate Wayne. In the draft, Philly was fortunate to steal tight end L.J. Smith out of Rutgers. If Correll Buckhalter could return to top form from a torn ACL and Brian Westbrook continued to develop, the team promised to be dangerous on both sides of the ball.

The Eagles, however, got off to a brutal start. In consecutive losses to Tampa Bay and New England, they were outscored 48-10. Donovan was awful in both games, completing less than 50 percent of his passes and throwing three interceptions.

Philadelphia began to turn things around in late September—though Donovan was still struggling. Reid had taught his team to win ugly, and five victories in November upped the club’s record to 9-3. Suddenly, in the topsy-turvy NFC, the Eagles were in position to secure homefield advantage throughout the playoffs (in their new stadium, Lincoln Financial Field). Donovan was also looking good. Over the campaign’s final two months, he tossed 13 TDs against only four INTs.

Though Philly dropped its second-to-last game to San Francisco, the team bounced back to defeat Washington. At 12-4, the Eagles were the conference’s top seed.

But all was not well in Philadelphia. Westbrook was done for the season with an ankle injury, and so was linebacker Carlos Eamons. The banged-up Eagles hosted the Packers to open the post-season, and won 20-17 in overtime. The victory was miraculous in more than one way. Philly fell behind 14-0 in the first quarter, and trailed again by three points with just over two minutes remaining. Then, on fourth and 26, Donovan hit Freddie Mitchell for the most unlikely of first downs. David Akers tied the contest to end regulation, then booted the game-winner in OT. Donovan enjoyed one of his best efforts of the year, going 21 for 39 for 248 yards and two scores.

The Eagles next prepared for the surging Carolina Panthers. To the consternation of the hometown fans, they laid an egg, losing 14-3. The offense was completely stymied, particularly Donovan, who had little time in the pocket and was forced into several crucial errors. The situation grew even more dire when Donovan suffered separated rib cartilage on a late hit by Mike Rucker. He tried to play despite the pain, but couldn’t continue. Koy Detmer took his place, and was equally ineffective.

Going into the 2004 campaign, the Eagles decided they had to take some pressure off their quarterback. The club strengthened itself on defense by signing free agent Jevon Kearse, and installed Westbrook as the feature back. But, without question, the biggest move was the acquisition of Terrell Owens, who forced a trade to Philly after the 49ers tried to deal him to Baltimore. The All-Pro receiver gave Donovan the first real outside threat of his Eagle career.

The duo clicked immediately. In the '04 opener against the Giants, Donovan connected with his newest teammate for three touchdowns. Owens also contributed when he wasn't catching passes, drawing double teams that freed up everyone else on the field. At the end of the day, the Eagles had a 31-17 victory, and Donovan threw for 330 yards.

It was more of the same the following week against the Vikings, with Philly winning 27-16 on Monday Night Football. Donovan passed for 245 yards and two more touchdowns, but most impressive, he didn’t turn the ball over for the second game in a row. He had struggled at times in this area in 2003. Owens impact was again evident against Minnesota, as Donovan found him on a pretty 45-yard scoring toss. With the TD, Owens topped the production of every Eagle receiver from the previous season.

Philadelphia continued to roll into October. With Donovan off to such a hot start, it became even easier for Reid to mix up his play calling. In a laugher over the Lions, Donovan piled up 356 yards and two touchdowns through the air, and also ran one in at the goal line. A week later, in a defensive struggle against the Bears, Westbrook answered the call with 115 yards rushing. Philly won 19-9.

The Eagles survived a scare in Cleveland the following Sunday. Donovan's 28-yard scamper in overtime helped set up the game-winning field goal by Akers. Philly was handed its first loss a week later in Pittsburgh, but at 7-1 the team had clearly established itself as the class of the NFC.

Donovan responded to the Steeler defeat with four monster efforts in victories over the Cowboys, Redskins, Giants and Packers. Over the stretch, he threw for 14 touchdowns against only one interception. He was particularly effective against Green Bay, completing his first 14 passes of the game en route to a 464-yard, five-TD performance.

On cruise control with the conference's best record, the Eagles hit a major pothole in December when Owens fractured his right leg against the Cowboys. The injury threatened to stop Philly dead in its tracks. While the rest of the offense had gelled nicely around Donovan and Owens, the pair's chemistry in the passing game was the key to the team's high-powered attack. At 13-3, the Eagles held homefield advantage in the playoffs, but questions remained whether they could flourish without Owens.

Donovan answered the doubters in Philly's playoff opener against the Vikings. Playing a nearly flawless game, he completed 21 of 33 passes for 286 yards and two touchdowns. His favorite target was Mitchell, who stepped up with five key receptions, including a touchdown. On defense, meanwhile, the Eagles kept Daunte Culpepper and Randy Moss in check. The result was a 27-14 victory, and another trip to the NFC Championship Game.

Michael Vick and the Falcons visited Lincoln Financial Field with the conference title on the line. The weather seemed to cooperate with the Eagles. The day was cold and windy, and the turf was frozen. The Philly D again showed its championship colors, shutting down the vaunted Atlanta running game and confusing Vick with different looks in the secondary. On the other side of the ball, Donovan did everything asked of him. Orchestrating a more conservative game plan, he threw two more TDs, avoided any INTs, and led his team to a convincing 27-10 victory.

For Super Bowl XXXIX, everyone turned their attention toward Owens. Despite warnings from team doctors, he vowed he would play. Donovan and the rest of the Eagles didn't mind the media coverage devoted to the receiver. It allowed them to focus more intently on their opponent, the Patriots, who were gunning for their third NFL title in four years.

With New England's penchant for mistake-free football in big games, the pressure was on Donovan to play just as smart. He came out on Philly's first possession looking for Owens, who made good on his promise and was ready to go. Neither team could mount a drive early, and they traded punts. Midway through the first quarter, however, Donovan committed the first crucial error of the night, floating an ill-advised pass to Westbrook in the red zone. Safety Rodney Harrison picked off the wobbler, and the Eagles missed a golden scoring opportunity.

The turnover set the tone for the rest of the contest. Donovan was brilliant at times, but downright sloppy at other points. He threw two more interceptions, and managed the clock poorly in the fourth quarter with the Eagles trailing by 10. A late scoring strike to Greg Lewis cut the deficit to a field goal, but Philly got no closer and lost 24-21.

While some teammates claimed Donovan was deathly ill for a good part of the game, he offered no excuses afterwards. His stats looked good enough—357 yards passing and three TDS—but his turnovers killed two drives, and he also missed several open receivers for potential huge gainers.

There will undoubtedly be a lot more big games in Donovan's career, and no one would be surprised to see the Eagles go all the way as he gains more patience and experience. His '04 numbers suggest he has finally come into his own. Donovan enjoyed easily the best year of his career, including 3,857 yards passing, 31 touchdowns (and just eight INTs), and a 104.7 QB rating. The presence of Owens obviously provided a major boost, but Donovan also demonstrated better decision-making skills and more confidence when he dropped back to pass.

That does not mean Donovan will become a pocket passer—if anything it will make him even more dangerous when he runs. In the meantime, the team continues to surround Donovan with a mix of rookies and veterans picked for their ability to complement his skills, and coach Reid and his staff keep trying to come up with new ways to maximize his remarkable athleticism. Like most NFL teams, Philly pins its regular-season hopes on its defense. But once the playoffs begin, look out—Donovan may be ready to leap tall buildings in a single bound.

DONOVAN THE PLAYER

Donovan has been cast as the poster boy for a new generation of do-everything athletic quarterbacks. Few would argue with this choice. Defensive coordinators despise him, for he buys his team the one thing they can't defend against: time. Throw a containing rush at him and he will use that extra second against you with his powerful arm and expert vision. Flush him out of the pocket and you flush your pass rush away; Donovan is as good throwing on the run and at odd angles as anyone in the league. And God help the defense that lets him get loose past the line of scrimmage. The more time he has to make up his mind, the more frightening the consequences.

As a passer, Donovan's technique has improved dramatically over the last couple of seasons. He always had a big arm, but now he knows when to take a little off touch passes and how to get some air under his longer deliveries. This is basically a function of the patience he has developed. Contrary to popular belief, Donovan was not a freewheeling signal-caller when he first got the starting nod for the Eagles. He stuck too long with his primary receiver, and did not adjust well to new defensive schemes. He ended up eating a lot of balls he should have thrown, which is the opposite of most NFL neophytes.

Donovan's most striking quality has nothing to do with throwing a football, however. It's actually the one he possessed back when he was the ebony-skinned newcomer in the lily-white suburb. He is hard not to like, and impossible not to respect. Teammates trust Donovan. It is a bond that translates onto the field and into the huddle. When the big guy talks, people listen. And they know if they do their jobs, he'll make sure they all get the job done.