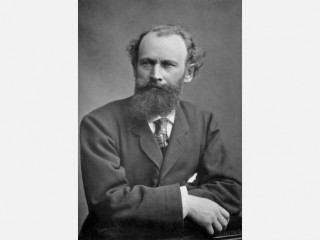

Édouard Manet (En.) biography

Date of birth : 1832-01-23

Date of death : 1883-04-30

Birthplace : Paris, France

Nationality : French

Category : Arts and Entertainment

Last modified : 2010-07-23

Credited as : Artist painter, book illustrator,

1 votes so far

"He's one of those painters considered so influential, people don't even bother with his first name," noted a report on CBS News Online. "Looking at his work now, it's hard to imagine that Édouard Manet was ever regarded as revolutionary, but he was." Manet is considered the father of modern art, and his work inspired the impressionist movement. Though he led a conservative life with respect to social custom, he rejected the traditions of the formal art world and ultimately helped to turn that universe upside down. Manet advanced the very modern view that artists had a responsibility to tell the truth in their work--whether that truth was beautiful or ugly. He met with constant criticism and abuse during his career but clung stubbornly to his forward-looking view of art's mission.

Although his innovations ushered in new and important movements in the history of art, Manet had an often difficult career. His works, often drawn from his contemporaries and themes from everyday Parisian life, aroused ire and scorn in their day from among the city's conservative artistic community and from the general public. He struggled for much of his adult life with his own self-doubts, fueled by the controversies that his work stirred, but enjoyed the consistent and enthusiastic support of painters and writers who would become some of the most prominent names in nineteenth-century culture. As John Canaday stated in Smithsonian, "An innovator with a strong sense of tradition--inspired, in fact, by such Old Masters as Raphael, Titian, [Diego] Velàzquez and [Francisco] Goya--Manet suffered deeply from his early notoriety as an outrageous renegade and, off and on for the rest of his life, from recurrent humiliating rejections by the officialdom of French art. He was revered by other artists we now recognize as his major contemporaries, and he gained the allegiance of such critics as had the perception and the courage to go against the current."

Manet was born in Paris, France, on January 23, 1832, to Auguste Édouard Manet, an official at the Ministry of Justice, and Eugénie Désirée Manet. A stern man who lived by a strict routine, the senior Manet had determined that Édouard, too, would be a lawyer. Manet's mother was very different from her husband. She had grown up in a sophisticated, worldly home and possessed great artistic and musical talents. She encouraged Édouard in his art, though considering her husband's feelings on the matter, such encouragement was most likely kept secret.

Manet detested the local schools he attended; his poor grades would perhaps have hastened his forcible departure from these institutions had his father not been so influential. At sixteen years old, Manet announced to his father that he wanted to become a painter. Because Auguste vigorously opposed his son's wish, a career of naval officer was decided upon as a compromise. Édouard spent six months on a ship sailing to Brazil and found it no less tedious than school; he subsequently failed the naval academy examination twice.

Begins Art Career

Manet finally prevailed over his father's objections, and in 1850 he entered the school of a well-known painter, Thomas Couture. At that time art in France was ruled by the Institut de France, the government's department of culture. Academic art was dominated by standards of beauty and grandeur that derived from ancient Greek and Roman culture; these centuries-old traditions and the limited scope of approved subjects--generally figures from classical mythology and the Bible--formed a climate that more adventurous artists found stifling. Nonetheless, any artist who hoped to be successful had to submit to such standards and enter works in the yearly salons, exhibitions arranged by the government and judged by members of the Institut's École des Beaux Arts.

Manet disliked the academic style from the beginning and insisted on drawing the models who posed for his class as they really looked, rather than refining his depictions to fit the classical standard of beauty and proportion. Sometimes he shocked the instructor by drawing clothes on the model and putting a cigarette between the sitter's fingers or a beer glass in the model's hand, rather than portraying an idealized pose from ancient statuary. Although Manet loved art and possessed the essential painterly skills, he also reveled in modern life and longed to put it on canvas. Paris in the 1850s teemed with precisely the sort of vitality he sought to memorialize; Manet often wandered through the city with his sketchbook, drawing whatever struck his fancy. He argued constantly with his teacher about art and modernity. Few artists had tackled subjects that were not noble, heroic, or historical, just ordinary and immediate. According to Canaday in Smithsonian, "Manet ran into trouble as a realist who rejected the prettification, the sugary idealism, the mythological travesties and inflated heroics typical of Salon demonstration pieces. He painted instead the world around him as he saw it and enjoyed it. While still a student in the lycée in the 1840s, according to his friend Antonin Proust, he declared, 'We must be of our time and work with what we see.' It became the guiding principle of his art."

Dutch portrait painter Rembrandt, Spanish court painter Goya, and French caricaturist Honoré Daumier may have provided some inspiration for Manet in this respect, but he had few predecessors in his quest to take painting out of the conservative tradition of the salon and into the street. Even after a trip to Italy in 1853, where he viewed and copied the works of the masters Michelangelo and Titian, Manet could not accept the constraints of the academic style. Around 1856, he made extensive travels through Germany, Belgium, and Holland. Prior to that, he had fathered a child with a young Dutch woman, a pianist named Suzanne Leenhoff.

Spanish art and culture enjoyed considerable popularity in France during this time, and the work of seventeenth-century court painter Velàzquez strongly influenced Manet, particularly the Spanish master's colors and spatial structure. The opening of Japan to the West in the mid-nineteenth century brought Japanese woodblock prints to Europe; radical French painters, Manet included, found them especially compelling. Manet experimented in his drawings and etchings with the flat space and heavy black outlines typical of these woodcuts. A third important influence on Manet was photography. When Louis Daguerre announced his new invention in Paris in 1839, he created a sensation. To young artists like Manet, this astonishing technology provided a new window on the world.

Stirs Controversy at the Salons

The first painting Manet submitted to the Paris Salon, 1859's The Absinthe Drinker, challenged virtually every tenet of the academic philosophy. He used a street-dweller he knew as the model for this portrait of a drunken vagrant. Employing a sharply limited range of colors, mostly browns and blacks, Manet posed the figure against a wall with a vague background. This "unpleasant" person in an "ugly" setting was of course rejected by the salon jury, as were many of Manet's paintings over the years. During this period he painted a variety of works with popular Spanish themes, such as The Dead Toreador, and portraits of street people like The Street Singer. Despite the familiar subjects--which were in themselves outside the norm--his unusual use of color, flat spaces, dark outlines, and frequently disorienting representations eluded the understanding of both the art establishment and the general public. Viewers felt threatened by Manet's paintings, which seemed to jump off the canvas at them. Their reactions did not go unnoticed by the artist, observed Kathryn Linderman in Investor's Business Daily. "Though Manet was mocked widely, he refused to change," Linderman wrote. "In fact, he used the criticism as motivation to keep painting. 'This war of daggers has done me a great deal of harm,' he said. 'But it was also a stimulus for me.'"

Manet's first taste of success came with the first of his works to be accepted into the Salon. In 1861, a canvas Manet called Le Guitarrero (The Guitar Player) won a second-prize medal, though some senior Academy members found it too radical in its realism; depictions of mythology, biblical themes, portraiture of the aristocracy, and other such rarefied subject matter were almost the only subjects deemed appropriate for art at the time. Contrastingly, Le Guitarrero depicts an ordinary street singer seated and clad in traditional Spanish garb, some onions and a jug of perhaps wine at his feet.

The year 1863 was pivotal for Manet. He gained considerable fame--though of the least desirable sort--thanks to an audacious work that would eventually be considered a masterwork. The painting, which he submitted to the salon that year, provoked responses ranging from wild laughter to complete outrage. Manet submitted Le Déjeuner sur l'Herbe (Luncheon on the Grass) at the Salon, which was summarily rejected. Works by other innovative artists were also rejected, and the artists protested so vehemently that the Emperor Napoleon III declared they would be exhibited separately, in what came to be known as the Salon des Refusés. Le Déjeuner sur l'Herbe caused an enormous scandal. It depicted two finely-dressed men lunching in a bucolic park setting together with a young woman who is completely unclothed. She gazes frankly at the viewer. It was deemed shameless and vulgar. In Déjeuner, Manet seemed to be toying with his audience by setting up the kind of traditional scene they might expect, then overturning those expectations. According to Jed Perl in the New Republic, "Manet's casual hedonism . . . combined elements of frankness and fantasy in ways that could leave Parisians wondering exactly what he had in mind. Even his friends weren't sure. Manet was not inclined to pronounce on artistic matters, and seemed content to leave the mystery intact."

In 1863 Manet again journeyed to Holland, but this time in order to study painting with Leenhoff's father; the couple married that same year. The family, often including Manet's mother, spent summers in the country, where Manet painted local scenes. In Paris, however, he became the leader of a group of young artists and writers who rejected academic painting and sought a modern vision. Among these were Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Claude Monet, Paul Cézanne, Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro, and Henri Fantin-Latour. They engaged in passionate discussions in cafés and in Manet's studio and eventually became the core of the impressionist movement. But, as Robert Hughes noted in Time, Manet "never exhibited with the impressionist group; his aims were not compatible with theirs, much as they respected one another. Manet's firmly built structures of light and dark were mostly done indoors, after many preliminary studies; they have the formal diction of studio art, not the light, open qualities of plein-air painting. Atmosphere and local color were not his prime issues. And when he took what seems, on first glance, an 'impressionist' subject, he was apt to load it with ironies and contradictions until its straightforwardness evaporated."

Manet continued his innovations in color, space, and outline despite persistent criticism, waiting only two years before shocking the art world once more. In 1865 another risqué work, Olympia, was accepted by the Salon. Again, a near-riot ensued, and pregnant women were enjoined to stay away. Although nudes were far from an unusual depiction in the history of art up until that point, it was the frank gaze of Manet's reclining young woman--her only adornment the ribbon around her neck and a flower in her hair--that aroused scorn and derision. As John Carmen observed in the San Francisco Chronicle, "The main reason Olympia provoked gasps when it was first shown publicly, in 1865, was that the subject was real and not idealized. She was a prostitute, devoid of mythological or heroic ideals, who gazed brazenly from the canvas as her servant delivered an admirer's bouquet." It is difficult for contemporary viewers to imagine the outrage the work provoked in 1865. It was called wicked, shocking, and ugly. Manet considered it his masterpiece.

A Change in Tone

In the late 1860s and into the 1870s, Manet's works adopted some new elements, partly as a result of his friendship with painters like Berthe Morisot--who became his sister-in-law--Degas, and Monet. During their summers in the countryside around Paris, these painters set up their easels outdoors and tried to capture the vivid sunlight, brilliantly colored clothing, and rich vegetation they saw. Such works as Boating, Claude Monet in His Floating Studio, and Argenteuil display Manet's utter departure from the academic tradition, with his loose brush strokes, intimate sense of space, and, most particularly, modern subject matter.

In 1875 Manet developed a debilitating disease, a slow deterioration of the central nervous system, which made it increasingly difficult for him to paint; he turned to smaller works and more flexible media like pastels and watercolors. His last large painting, Bar at the Folies-Bergère, was the most complete synthesis of his work and philosophy. It is a powerful "snapshot" of a barmaid, with all the liveliness of the bar reflected in a mirror behind her. The totality of Manet's style is evident--the immediacy of the moment depicted, the complicated space, the expressive brush strokes. A contributor to the Encyclopedia of World Biography wrote, "While we are drawn to the brilliantly painted accessories, it is the girl, placed at the center before a mirror, who dominates the composition and ultimately demands our attention. Although her reflected image, showing her to be in conversation with a man, is absorbed into the brilliant atmosphere of the setting, she remains enigmatic and aloof. Manet produced two aspects of the same personality, combined the fleeting with the eternal, and, by 'misplacing' the reflected image, took a step toward abstraction as a solution to certain lifelong philosophical and technical problems." Numerous attributes of this work have become defining characteristics of modern art.

In 1881 Manet was finally admitted to membership in the Legion of Honor, an award he had long coveted. By then he was seriously ill. Therapy at the sanatorium at Bellevue failed to improve his health, and walking became increasingly difficult for him. In his weakened condition he found it easier to handle pastels than oils, and he produced a great many flower pieces and portraits in that medium. In the spring of 1883 his left leg was amputated, but this did not prolong his life. He died in Paris on April 30, 1883. Summarizing the artist's career on BBC Online, a contributor observed that Manet "strove for a return to reality and a directness of presentation. He commented on this aim to record the world around him: 'I know not how to invent--if I am worth something today, it is thanks to exact interpretation and faithful analysis.'"

PERSONAL INFORMATION,/b>

Born January 23, 1832, in Paris, France; died April 30, 1883, in Paris, France; son of Auguste Édouard Manet (an official at the Ministry of Justice) and Eugénie Désirée Manet; married Suzanne Leenhoff; children: Leon. Education: Attended the Collège Rollin, Paris, 1844-48; studied art in studio of the academic painter Thomas Couture, 1850-57.

AWARDS

Chevalier de la Legion d'Honneur, 1881, Republic of France.