Duong Van Minh biography

Date of birth : 1916-02-19

Date of death : 2000-08-06

Birthplace : Cochinchina, French Indochina (now Tiền Giang Province, Vietnam)

Nationality : Vietnamese

Category : Politics

Last modified : 2011-03-04

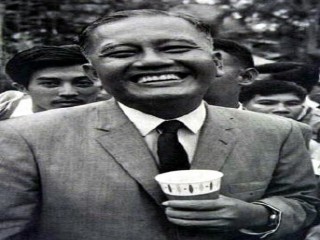

Credited as : Politician and general, former President of Republic of Vietnam, Big Minh

General Duong Van Minh was the first and last of a string of leaders who governed South Vietnam in the dozen years between the overthrow of President Diem and the fall of Saigon.

In 1963, Duong Van Minh represented pro-American, anti-communist values. By 1975 he remained the only figure of stature who could negotiate with North Vietnamese forces and avert a bloody end to the Vietnam War. Duong Van Minh's military career spanned decades of conflict. He gained an early reputation for bravery, honesty, and leadership in the field and quickly rose to national prominence. In his later career, however, power remained just beyond his reach and he was eventually forced into exile.

Minh was born into a wealthy Vietnamese family on February 19, 1916, in the Mekong River delta village of My Tho in Long An Province, just 35 miles southwest of Saigon. After graduating from a high school run by the French, Minh enlisted in the colonial army in 1940 and was commissioned a second lieutenant. He continued to serve under the French during World War II until Vietnam surrendered to Japan. At that point he joined a resistance group which was soon quashed. The young officer was taken prisoner for two months and tortured, having half of his teeth knocked out. For the rest of his life, his gold tooth-lined grin would be his trademark. Standing 5 foot 10 inches tall and athletic, he developed a pronounced stoop, supposedly from constantly leaning over to talk to his shorter companions. Minh was known fondly as "Beo" (fat boy) to his fellow soldiers. Americans later dubbed him "Big Minh" to distinguish him from another South Vietnamese official by the same name.

After his release by the Japanese, Minh returned immediately to the French, but was imprisoned for joining the resistance. He was jailed for an additional three months, this time in a crowded dark cell with no toilet. Driven nearly to insanity by the subhuman prison conditions, Minh won his freedom with the help of another prisoner, Nguyen Ngoc Tho, who would later become the premier of his country.

Minh's nationalist spirit grew during his incarceration, but he agreed upon release to serve the French for another four years under the puppet government of Emperor Bao Dai. When a Vietnamese army was created in 1952, two years before independence, Minh jumped at the chance to join. Soon he was on his way to the Ecole Militaire in Paris for further training, the first Vietnamese officer to be so honored. By the end of the French war against the Vietnamese nationalists, Minh was commander of the Saigon-Cholon garrison.

After the French withdrew from Vietnam, Ngo Dinh Diem became president of the Republic of Vietnam. Minh went to work for Diem's new regime, first earning the gratitude of his people in 1955 by vanquishing a gangster syndicate and later pacifying two religious cults. Minh distinguished himself by his respect for these sects' temples, even while giving no quarter to their fighters. His actions would put him in sharp contrast years later Diem, who showed no such regard when attacking Buddhist dissidents.

After his success in these campaigns, Minh was sent for yet more training at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. Upon his return, Diem chose Minh in 1958 to become the first commander of field operations in the developing war against Viet Cong guerrillas. Minh's success and popularity with his troops would later prove his downfall in Diem's eyes, however. As dissatisfaction among Vietnam's generals mounted, the president grew suspicious of Minh's loyalty. Though not openly critical of Diem, Minh privately questioned the wisdom of fighting a war against the communists without greater popular support in South Vietnam. Finally, Diem removed Minh's command and named him military advisor to the president. This effectively removed Minh from any direct power in the army and gave Diem a fleeting sense of security.

Diem became more erratic, tyrannical, and dangerously detached from his people in the early 1960s. Rumors circulated that he was secretly negotiating with Ho Chi Minh's North Vietnam to unify the country and declare neutrality. United States support, critical to Diem's survival, grew thin. There were whispers of a coup, and Minh seemed a logical choice to lead it, but the general insisted he had no stomach for politics but was content to play tennis, read French and American magazines, and tend to his orchid garden. He stated his commitment to preserving civil instead of military control in South Vietnam's government. Minh's dedication had impressed American advisors years earlier, however, when he had reportedly mortgaged his home and sold his car and furniture to finance under-funded army intelligence operations. It was clear the Americans were not content to let Minh continue raising orchids.

In November 1963, Minh led a military coup that toppled the Diem government, with the tacit approval of the United States. Minh offered him safe conduct if he surrendered within five minutes, but Diem reportedly hung up and attempted to flee dressed in the robes of a Catholic priest. Diem and his brother Ngo Dinh Nhu were later captured and killed, on orders from Minh, according to some accounts. Friends of Minh said he had acted out of patriotism and outrage at Diem's attacks on Buddhist temples, not personal ambition. The Kennedy administration showed little surprise or regret, but simply remarked that it would have preferred to have the brothers survive in exile.

The same qualities which endeared Minh to his people-his slow, diffident approach; his bashful, gawky demeanor; his honesty and integrity-quickly led Americans behind the scenes in Saigon and Washington to grow impatient. Under Minh, South Vietnam drifted into a serene normalcy, but this did not satisfy Americans who had hoped the pro-U.S. general would launch a tough offensive against communist insurgents. When Minh demonstrated reluctance to play the role which American advisors deemed essential to secure the South Vietnamese countryside, king-makers grew impatient.

President Lyndon Johnson sent Minh a pointed New Year's greeting, both pledging support and warning the general not to become soft on communism: "The United States will continue to furnish you and your people with the fullest measure of support in this bitter fight. We shall maintain in Vietnam American personnel and material as needed to assist you in achieving victory … The U.S. government shares the view of your government that 'neutralization' of South Vietnam is unacceptable." Neutralization, or a compromise settlement with the communists, was precisely what Minh favored. On January 30, 1964, Minh was toppled in a bloodless coup by General Nguyen Khanh, who soon received another message from Johnson: "I am glad to know that we see eye to eye on the necessity of stepping up the pace of military operations against the Viet Cong."

Bitter at the sudden withdrawal of American backing, Minh refused to cooperate for several days and was detained in his home. Students demonstrated in the streets demanding his return to power. Eventually he agreed to join Khanh's government as a figurehead. Before long, he was sent on a goodwill tour to Thailand and then refused reentry into Vietnam, effectively exiling him from his homeland. By the end of 1964, he had been forcibly retired from the military.

Though Minh received a pension which allowed him to live well with his wife in Bangkok-raising orchids, writing memoirs, playing tennis, and receiving visiting dissidents from Vietnam-he was far from content. In May 1965, he attempted to fly back to Vietnam but was humiliated when the Saigon airport refused him permission to land. In 1967, Minh tried another tack. He filed papers at the embassy in Bangkok to run for president of Vietnam from exile. Though this ploy was unsuccessful, he was allowed to return in 1968, as a gesture of goodwill. Though Minh kept a low profile, he continued to talk with dissidents and quietly proposed a "people's congress" to find a way out of the war and back to a government which reaffirmed the democratic ideals that prompted his coup against Diem. Minh came to symbolize hopes for a negotiated compromise with the North Vietnamese.

In 1971, Americans pressured both Minh and Vice President Nguyen Cao Ky to run against Nguyen Van Thieu in presidential elections. The U.S. government seemed more concerned with appearances than with promoting real democracy, and desperately sought to sign up and retain both men as candidates. Both went through the motions, but the campaign soon turned into a circus. Ky maintained that Thieu had "an excessive attachment to power, " and both candidates complained that the contest was patently rigged. The campaign gave Minh some opportunity to put forth his views on democratic reform and possible means to end the war, but the retired four-star general openly expressed fears that he could be sent back into exile if he advocated a coalition government with Ho Chi Minh.

Both opposition candidates eventually withdrew. In doing so, Minh said, "I cannot put up with a disgusting farce that strips away all the people's hope of a democratic regime and bars reconciliation of the Vietnamese people." Ky said he simply didn't want to be a clown.

Robert Shaplen, in the New Yorker, analyzed the debacle later: "The consensus is that by his antic and frantic efforts to guarantee his reelection, President Thieu has, for once, outsmarted himself. One way or another, his days are numbered."

Minh gradually increased his criticism of Thieu. In 1973, he openly deplored the government's repressive tactics. In 1974, he called Thieu's government "violence-thirsty, " and in 1975 he said, "The Government is now nothing but a tyranny." Minh demonstrated how he had earned his reputation for patience. As one friend said, "To grow one orchid takes four years. You cannot grow orchids in haste."

By April 1975, it was clear that South Vietnam would fall. Americans had lost their taste for pursuing the endless war and North Vietnamese troops stood poised just miles outside the capital. Thieu resigned on April 21, and was replaced by Vice President Tran Van Huong, Minh's old teacher and mentor. The concern in South Vietnam was no longer with winning the war, but simply with losing it as gracefully and safely as possible. In a last attempt to place a man in power who could negotiate with the communists, the National Assembly turned to Minh.

Minh took over on April 28. In his inaugural address he said, "The coming days will be very difficult. I cannot promise you much." Minh was on the radio reassuring his people two hours after the last American helicopter took off from the roof of the U.S. embassy, but the war was over. On April 30, he ordered his troops to lay down their arms. Minh was placed in detention by the victorious North Vietnamese. In 1983, he was allowed to emigrate to France.