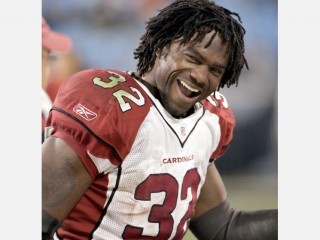

Edgerrin James biography

Date of birth : 1978-08-01

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Immokalee, Florida, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2010-08-12

Credited as : Football player NFL, currently plays for the Indianapolis Colts,

0 votes so far

Edgerrin Tyree James was born in Immokalee, Florida on August 1, 1978. His hometown boasts some of the best farmland the Sunshine State has to offer. And some of the worst neighborhoods. Located near the Everglades, about 50 miles inland of the southwest coast, Immokalee has a population of roughly 14,000except during the harvest season when it swells to nearly three times that size with migrant workers. The community is also known as fertile ground for disease and drugs. In the early 90s, it had the highest rate of AIDS per capita in Florida.

Edgerrin came from a huge extended family. One of his grandmothers had 13 kids, and he was never quite sure who to call an aunt, uncle or cousin. Edgerrins immediate family consisted of four brothers, a sister and his mother, Julie. His father, Edward German, worked as a harvesting contractor, a job that kept him away from Immokalee for long periods of time. Edgerrin has always maintained a good relationship with his dad, but he was never a major part of his life (partly because his parents never married).

For all intents and purposes, Julie raised her children by herself. To provide for her family, she spent long hours in a local school cafeteria preparing hundreds of meals a day. Her income, however, was not enough to pay for her own meals, as the family relied on food stamps to eat most weeks.

Poverty and hardship were all Edgerrin knew from the time he entered the world. He watched one of his grandfathers labor well into his late 70s, then just drop dead one day. He also saw several relatives succumb to the lure of the streets. Three of his brothers wound up in jail for a shooting incident, an uncle and a cousin died of AIDS, and another uncle was gunned down.

Edgerrin was no stranger to crime, either. Gifts rarely came at birthdays and on Christmas, so as a kid he sometimes helped himself to bikes left unattended by their owners. After repainting the stolen merchandise, Edgerrin enjoyed the fruits of his thievery.

Finding affordable housing was another problem for Edgerrins family. When Julie couldnt make the rent in one place, she packed up her kids and their belongings, and relocated to another dwelling. If things got really bad, they were always welcome to stay in a small apartment owned by Julies parents, Manies and Ann. Edgerrin and his siblings slept in a back room that doubled as the kitchen. The quarters were cramped, but everyone felt fortunate to have a roof over their heads.

It was during this time that Edgerrin developed his love of football. He played pick-up games with friends, on the streets and in nearby fields. His idol was Walter Payton. Edgerrin was so fascinated by Sweetness that he studied videotapes of the Chicago Bears star, then imitated his moves against real opponents.

By his 10th birthday, Edgerrin had joined the local Pop Warner football league. A punishing running back with tremendous speed, he dominated from the start. Before long, everyone was calling gameday the Edgerrin James Show.

Football wasnt the only form of entertainment discovered by Edgerrin and his friends. They would gather on a corner, beg for money, and then buy hits of crack for down-on-their-luck junkies. The only condition was that the crackheads smoke right in front of the boys. They got a rush observing the effect the drug had on its users. Edgerrin, however, never felt the urge to try the stuff himself. He knew from firsthand experience how crack could ruin lives.

Edgerrin didnt have much time for drugs, anyway. If he wasnt on the football field, he was in a watermelon patch earning money to support his family. Beginning in the summer of 1993, he made seasonal trips to southern Georgia where he worked 16-hour days in the sweltering heat loading watermelons onto trailers. His strength and stamina were legendary. Indeed, no one could bump watermelons better or longer than Edgerrin.

Edgerrin used his summer earnings to buy a car. This newfound freedom eventually led him to Miami, where he gave himself a memorable makeover. He had five teeth capped in gold, and later had his hair rearranged into dreadlocks. Needless to say, it wasnt hard to spot Edgerrin at Immokalee High School.

It was much harder to find him in class. Football was the only thing that really interested Edgerrin, and when he wasnt cutting class he was barely paying attention. This nearly caught up with him when it came time to sort through scholarship offers.

ON THE RISE

Those offers were made to a young man who cultivated his skills as a sophomore and junior, then came into full bloom by his senior season. The year was 1995, and Edgerrin was ranked among the finest runners in the state. At six feet tall, he was a shifty, powerful back with breakaway speed. He also played a mean linebacker and performed placekicking duties.

For Edgerrin and the Indians, the 95 campaign was disappointing. He missed half the year with a dislocated elbow, and the team finished 5-5. Still, Edgerrin was impressive enough to be named a Parade All-American. Despite the seniors obvious talent, many big-time football schools had questions about him. Not only was there the elbow injury, but his poor academic performance also raised red flags.

When Edgerrin failed to earn an acceptable score on his first stab at the college entrance exams, only a handful of major programs recruited him seriouslyand only one, Ohio State, was from outside Florida.

Miami coach Butch Davis appeared more willing than anyone else to roll the dice on Edgerrin. In his second season with the Hurricanes, Davis was rebuilding a program devastated by NCAA sanctions. Though he had only 12 scholarships at his disposal, he simply couldnt pass on someone with as much potential as Edgerrin. When the youngster finally scored high enough on his ACT, he was off to the Miami campus.

According to the experts, the Hurricanes were the team to beat in the Big East in the fall of 1996. After a slow start the previous season, Miami had finished strong at 8-3. With 19 starters returning from that club, Davis welcomed back a deep and experienced group. At quarterback, Ryan Clement had emerged as a team leader. His primary weapons were All-Big East tailback Danyell Ferguson and a potent pair of receivers, Jammi German and Yatil Green.

If the Hurricanes were to encounter problems, they probably would come on defense. With Ray Lewis opting for the NFL, James Burgess had big shoes to fill at middle linebacker. Along the line, Kenny Holmes and Kenard Lang were strong at the ends, but tackles Denny Fortney and Marvin Davis needed to prove themselves. In the secondary, speedy safety Tremain Mack was the best of a solid, but unspectacular group.

The optimism in Miami died before the season began. First, five players were arrested on felony charges. Next, German tore the ACL in his right knee, then was suspended for his role in an on-campus brawl. Ferguson went down with an injury too, which forced Davis to start back-up Dyral McMillan. The coach also turned to Edgerrin, who was supposed to spend the year as a redshirt. The freshman, however, responded to the call. In seven games, he rushed for 446 yardsa frosh record at Miamiand two scores. His 105 yards on the ground against Temple made him the first Hurricane true freshman to eclipse the century mark since 1987.

Edgerrins performance versus the Owls helped produce one of Miamis eight wins during the regular season (against three losses). The Hurricanes shared the conference championship with Virginia Tech, then beat the Virginia Cavaliers in the Carquest Bowl, 31-21.

Heading into 1997, the Miami program was under the microscope. The off-field problems from the previous season gave critics even more ammunition in their attacks of the team. To help repair the squads tarnished image, the school instituted Canes on Patrol, a community service project that teamed players with police on tours of some of Miamis worst neighborhoods.

On the field, however, Miami was a different story. Thanks to the teams high-powered offense, most preseason guides ranked the Canes high in the Top 20, and considered them a contender for the national crown. Leading the charge was Clement, who was going into his third year as the starting signal-caller. He received good news when German came back from his injury at full speed. The ground game was strong, too. McMillan entered training camp No. 1 on the depth chart, but Edgerrin was not far behind. Davis knew it would be foolish to keep the sophomore star on the sidelines.

Again, defense was the coachs major concern. Only three starters returned, which put the pressure on a slew of unproven underclassmen. Chief among them were a pair of freshmen, right tackle Damione Lewis and linebacker Dan Morgan. Davis was hesitant to give either youngster too much responsibility, but realized they were key to a successful campaign. Unfortunately for the Canes, their inexperience caught up with them. Miami went 5-6 overall, and just 3-4 in the Big East.

One of the few bright spots for Miami was Edgerrin. Indeed, by the end of the year, he had established himself as one of the nations best backs. Though he started just six games, he topped the Hurricanes in rushing with 1,098 yards (the second-highest total in school history) and scored 13 TDs on the ground, which also set a new Miami record. To no ones surprise, Edgerrin made every All-Big East team, including those named by AP and The Football News.

During the season, Edgerrin also became a father, as his girlfriend, Andia Wilson, gave birth to a girl, Edquisha. The arrival of his daughter changed his life greatly. The following summer, though Edgerrin had originally committed to working out in Miami, he drove home every day to check in on Edquisha.

Driven also described the 20-year-olds mindset heading into his junior campaign. With his sights now set on an NFL career, Edgerrin wanted to show scouts he could thrive under the constant pounding of enemy defenses. But in Daviss running back rotation, he was slated to share time with Najeh Davenport and James Jackson. Edgerrin told his coaches, teammates and the press that he wanted to carry the load by himself.

The rest of the team lacked their stars self-assurance. Despite the presence of Edgerrin, questions riddled the offense. Clement had graduated, leaving the quarterback duties to Scott Covington. Sophomore receiver Reggie Wayne, the Big East Rookie of the Year, had to show he was no fluke. The offensive line featured talent and depth, yet Davis admitted it was his biggest worry.

The coach felt much more confident in his defense. Lewis and senior Michael Lawson anchored a solid front four that promised to give opponents fits. Morgan was the best of a versatile linebacking crew, and the young secondary boasted great speed and hard hitters.

The campaign started on the right foot with easy wins over East Tennessee State and Cincinnati. Then came a tough loss at home in OT to Virginia Tech. Miami split its next two, including a defeat in the Orange Bowl to Florida State. At 3-2, the Hurricanes looked like an ordinary team. That was until Edgerrin shifted into another gear.

In October at West Virginia, he began a stretch of six-consecutive games with 100-plus rushing yards. Against the Mountaineers, he ran for 162 yards and three touchdowns, a performance that earned him honors as the Big East Player of the Week. The following week, he became Miamis first back-to-back winner of the award when he torched Boston College for 182 yards and two more scores. The Canes won both contests, then beat Temple and Pittsburgh to up their record to 7-2. The teams good play ended with a thud at Syracuse in the Carrier Dome, however, as the Orangemen routed Miami, 66-13.

With only one regular-season game left, a home tilt against UCLA, Miami had nothing to play for but pride. The Bruins, on the other hand, were undefeated and dreaming of a national championship. Riding a 20-game winning streak, UCLA entered the contest second in the BCS rankings. A victory would guarantee them a berth in the Fiesta Bowl and a shot at #1.

Miami took a 21-17 lead in the first half, as the teams traded big plays. Edgerrin was the star, running for 173 yards by intermission. In the third quarter, UCLA seized the momentum as quarterback Cade McNown guided his team to three touchdowns. But Edgerrin and the 'Canes refused to go quietly. Trailing 45-42 with less than a minute remaining, Miami moved the ball deep in UCLA territory. Davis then called Edgerrins number for the 39th time of the day, and the junior plowed in from the one-yard-line. Amazingly, McNown had one last rally left in him, but two desperate heaves from inside the Miami 30-yard-line fell incomplete. The Hurricanes won, 49-42.

On the strength of its victory over UCLA, Miami received an invitation to play North Carolina State in the Micron PC Bowl. The 'Canes cruised, 46-23, as Edgerrin enjoyed another big day with 156 yards and two scores.

With 1,416 yards and 17 TDs, Edgerrin turned in the greatest rushing season in school history. The first Hurricane to surpass 1,000 yards in consecutive years, he was named First Team All-Big East and Second Team All-America.

Miamis emotional finish to the 1998 campaign gave Edgerrinnow projected as a first-round NFL picka lot to think about. The prospect of winning a national championship made a return for his senior season very tempting. So did the thought of winning the Heisman Trophy.

Family obligations, however, were more pressing. Edgerrin had the future of his daughter to consider, not to mention his mothers well-being. Ultimately, he felt he had no choice, and declared himself eligible for the NFL draft.

Edgerrins decision changed the entire outlook of the draft. All along, Ricky Williams, the all-world halfback from Texas, had been regarded as the best runner available. With Edgerrin in the picture, NFL scouts had to reorder their depth charts. At 6-0 and 214 pounds, he had the size that pro coaches craved, and his speedsub-4.5 in the 40was also impressive.

Edgerrin, however, scared off some with his attitude and appearance. Given his background, some wondered whether he would be distracted by the fame and fortune of the NFL. Others took one look at the dreadlocks and gold teeth and dismissed him almost immediately.

One of the teams that couldnt afford to write off Edgerrin was the Indianapolis Colts. Owner of drafts fourth pick, the team had let Marshall Faulk walk away as a free agent, and now desperately needed a back to complement Peyton Manning, Marvin Harrison and a steadily improving passing game. GM Bill Polian knew that adding a punishing runner would make the Indy offense even more difficult to handle. His choice came down to Edgerrin and Williams, and he went with the Miami star.

While many NFL insiders applauded the move, fans in Indianapolis werent nearly as enthusiastic. To them, Williams had the better stats and pedigree; picking him was a no-brainer. They screamed even louder when Edgerrin held out of training camp, refusing to suit up until a deal was finalized.

Edgerrin made the situation all the more difficult by handing the negotiations over to his brother, Ed German Jr., and two friends, Pierre Rutledge and Tyrone Williams. But upon learning that he could not sign a deal without representation from a certified agent, he dropped Team Edgerrin and hired Leigh Steinberg, who counseled him to sit out until a contract was in place.

The Colts, meanwhile, struggled to find a running game, rushing for a meager 34 yards on 24 carries in their first exhibition contest. Adding injury to insult, halfback Darick Holmes broke his leg. Backed into a corner, Indy inked Edgerrin to a seven-year deal a few days later. With incentives, the deal was worth as much as $49 million.

MAKING HIS MARK

Edgerrin clearly gave the Colts a huge boost. But coming off a 3-13 season, Indy still had a long way to go. The strength of coach Jim Moras team was its young offense. After only a year in the pros, Manning had proved he was the real deal. His favorite target was Harrison, though finding a pass-catcher to complement him remained a top priority. With that in mind, offensive coordinator Tom Moore planned to use Edgerrin as a receiver out of the backfield as often as possible. The Colts also expected the kicking game to put points on the board, thanks to the booming right leg of Mike Vanderjagt.

Defensively, Indianapolis had lots of holes. Mora hoped to fill some of them with the hiring of new defensive coordinator Vic Fangio, who was known for his attacking, blitzing style. The Colts also signed several free agents, including linemen Chad Bratzke and Shawn King. At linebacker, an aging Cornelius Bennett provided leadership, while cornerbacks Tyrone Poole and Jeff Burris were the best of a suspect secondary.

Behind an impressive debut from Edgerrin, Indianapolis hinted in Week 1 that it might be better than the experts predicted. In front of a packed house in the RCA Dome, the team routed Buffalo, 31-14. Edgerrin gained 112 yards on 26 carries to become just the fourth Colt to go over the century mark in his first game. The following week at New England, however, he wore the goat horns after fumbling on his own 37-yard-line with the score tied and just over two minutes remaining. The turnover set up the game-winning field goal by Adam Vinatieri, who capped a 21-point comeback victory by the Pats.

Edgerrin and his teammates shook off the New England loss with a win over San Diego, then suffered another aggravating defeat at home, as Miamis Dan Marino passed the Dolphins to a 34-31 victory. The Colts ended the month at .500, but felt like they should have been 4-0.

Mora agreed. With Edgerrin in the backfieldhe was named the NFLs Offensive Rookie of the Month after running for 276 yards and two scoresIndys offense was nearly unstoppable. If the defense matched that effort, the Colts had a chance to make some real noise in the AFC.

The coach got what he was looking for against the New York Jets. In a hard-nosed defensive battle, Indianapolis beat Gang Green, 16-13. Edgerrin rushed for 111 yards, doing much of his damage between the tacklesa revelation for a team that had struggled in short-yardage situations in years past.

The victory over the Jets ignited a streak that saw the Colts win 10 in a row. They cruised at home against the Cincinnati Bengals, Dallas Cowboys and Kansas City Chiefs, and on the road over the New York Giants and Philadelphia Eagles. The victory over Philly demonstrated how lethal the teams three-headed offense could be. Edgerrin had 152 yards and two touchdowns, Manning passed for 235 yards and three touchdowns, and Harrison caught five balls for 60 yards and one TD.

By now, the three stars had developed into good friends. They met every week at the St. Elmo Steakhouse in Indianapolis, where they discussed everything from football to their personal lives. Every day the trio arrived at practice early, then stayed late to perfect their timing with one another.

Edgerrin never seemed to take a break. He showed up at Indys training facility at 6:30 a.m. to watch film, regularly sought out the advice of veterans and kept his body lean and toned. As the season progressed, he was asked to carry more of the load on offense, often getting more than 30 touches a game. The days in the watermelon patches were paying big dividends.

In November, he became the first player in NFL history to be honored as the leagues Offensive Player of the Month and the AFCs Offensive Rookie of the Month.

The Colts moved into December with an opportunity to post the conferences best record and secure homefield advantage throughout the postseason. For a team not expected to reach .500, this was almost too good to believe. Victories over the Washington Redskins and Cleveland Browns brought Indy to 13-2, but a loss at Buffalo enabled the Pittsburgh Steelers to take the AFC regular-season crown.

Still, the Colts earned a first-round bye and at least one home playoff game. The week off, however, did little to help Indianapolis against the Tennessee Titans. Coming off a miraculous Wild-Card victory over Buffalo, the underdogs manhandled the Colts in the RCA Dome. Though Indy took a 9-6 lead into halftime, Tennessee was winning the war in the trenches. When Eddie George broke free for a 68-yard touchdown run in the third quarter, the Titans sealed their upset victory. Edgerrin had one of his worst days of the year, rushing for 56 yards on 20 carries.

Still, it was hard to diminish what had been a flat-out sensational rookie campaign. Edgerrin ran for an NFL-best 1,553 yards, tied for first with 17 total touchdowns, and his 2,139 yards from scrimmage were just 73 short of the leagues rookie record. Named First Team All-Pro by the Associated Press, Football Digest, Pro Football Weekly and USA Today, he was also tabbed NFL Rookie of the Year by The Sporting News and Sports Illustrated.

In the off-season, James returned to Immokalee, where he spent quality time with his daughter. He also commuted to his alma mater almost every day for a series of grueling workouts. Focused on a championship run in 2000, he showed up at training camp with t-shirts that read Back On The Grind. (Ironically, he picked up the slogan from an uncle who was a drug dealer.)

The Colts faced different pressure heading into the 00 season. With the triumvirate of Edgerrin, Manning and Harrison leading the way, Indy was installed as a Super Bowl favorite. The defense, however, was still rebuilding. Rookie Rob Morris was inserted at middle linebacker, and another newcomer, outside linebacker Marcus Washington, was counted on to bolster the pass rush. Moras goal was to lessen the burden on the offense by creating more turnovers.

Indianapolis opened the season well, and by mid-November was in good position at 7-3. Manning and Harrison continued to mature as one of the leagues most dangerous passing combinations, while Edgerrin amazed everyone by actually improving on his rookie campaign. In a 37-24 victory over the Seahawks at Seattle in October, he gained a franchise-record 219 yards on the ground, plus three scores. A month later Edgerrin surpassed 1,000 rushing yards for the year, as the Colts beat the Jets at home. He also hit paydirt for the fifth game in the row, making him the first Colt to do so since Don McCauley in 1977.

Most impressive was the fact that Edgerrin was gaining strength as the season progressed, when his team really needed him. With three games left, Indy suddenly found itself in danger of missing the playoffs. Edgerrin responded to the challenge. Pacing the Colts to a trio of victories and a spot in the post-season, he carried the ball 79 times for 355 yards and three touchdowns, and also totalled 13 receptions, with another TD.

The teams spirited finish masked serous problems on defense, most notably the inability to stop the run. Indianapolis traveled to Miami for a Wild-Card matchup against the Dolphins, and fell 23-17.

Again, Edgerrins individual accomplishments helped put a positive spin on a disappointing end to the year. He ranked first in the NFL in rushing yards (1,709) and total yards (2,303), and became only the fifth back to win a rushing title in each of his first two seasons (matching Eric Dickerson, Earl Campbell, Jim Brown and Bill Paschal). With 18 TDs, meanwhile, he came within two scores of breaking Lenny Moores team mark. But for some reason Edgerrin was ignored by the media when it came time for post-season awards. Though an easy choice for his second Pro Bowl, he received no MVP votes and was left off the AP All-Pro team.

Motivated by the snub, Edgerrin attacked his offseason workouts with newfound vigor. But for many in the Indy organization, that wasnt enough. Rather than join his teammates for voluntary workouts in the spring, Edgerrin remained at home in Florida to train on his own. When he arrived at camp months later, he was criticized for being self-centered. Feeling persecuted, Edgerrin grew sullen and quiet. He and Mora rarely talked, and his relationship with running backs coach Gene Huey was even worse.

The Coltsagain touted as a potential AFC powerhousewere a team in turmoil. With Edgerrin unhappy and the defense shaky, Indianapolis had little margin for error. After winning their first two, they dropped eight of their next 10, then stumbled home to a 6-10 record. While Harrison enjoyed another sensational campaign, Manning threw 23 interceptions, and the club surrendered a league-worst 486 points. When Polian and Mora began to feud, the coach was shown the door.

Nothing had a bigger impact on Moras future than a season-ending injury suffered by Edgerrin, who tore the ACL in his left knee in late October at Kansas City. At the time, he was on pace for another huge year, having already rushed for 662 yards and three touchdowns. (He had also extended his reception streak to 38 straight games.) Without him, the Colts still featured a potent running gameDominic Rhodes became the first undrafted rookie to go over 1,000 yardsbut opponents no longer viewed the Indy offense with the same dread. Able to take more chances, enemy defenses made Mannings job a lot more difficult, and any hope of a winning campaign faded in Indianapolis.

Offseason changes came fast and furious for the Colts. The most notable was the hiring of Tony Dungy, who had been forced out as the coach of the Tampa Bay Buccaneers. He was known as a defensive genius who preferred to play things close to the vest on offense.

Dungy spent his first several months on the job weeding out players who didnt fit his system, and drafting and signing those who did. Rookies Dwight Freeney, Larry Tripplett and David Thornton all appeared to be Dungy guys, as did free agents Walt Harris and Greg Favors. Not surprisingly, all were fleet-footed defenders.

On the other side of the ball, the Colts lost several key contributors, including receivers Terence Wilkens and Jerome Pathon, and tight end Ken Dilger. But Dungy felt the key to his offense was limiting turnovers. While he retained the go-for-the-jugular Moore as his offensive coordinator, the coach planned to pull back on the reigns whenever the play-calling got too bold.

Dungy also liked what he saw from Edgerrin, whose recovery from knee surgery was progressing steadily. In fact, the problem may have been that the 24-year-old felt too strong. Players normally require a good year to regain full strength after a torn ACL. Edgerrin was trying to come back in nine months.

Though he started impressivelyincluding a 138-yard performance in a loss to MiamiEdgerrin wore down as the season moved along. Sore ribs and a pair of ankle sprains limited his production throughout October, and forced him to sit out the first two games of November. Edgerrin appeared refreshed when he returned to action, helping the Colts to two wins in a row. But in December he was largely ineffective, and finished the campaign with just 989 yards rushing and two touchdowns. Edgerrin averaged only 3.6 yards per carry, and his longest run was 20 yards. His receiving stats (61 catches for 354 yards and a TD) were down, too.

To his credit, Dungy found a way to turn the Colts around. Behind an improving defense and more conservative offense, the club went 10-6 and earned a Wild-Card berth against the Jets. Unfortunately, Indy unraveled in the Meadowlands, losing big in a 41-0 blowout.

Unlike years past, the playoff rout didnt create undo panic in Indianapolis. Dungy stuck to his guns, and identified the shortcomings in his defense and offense. Second-year linebacker David Thornton was inserted into the starting lineup, along with two newcomers in the secondary, Mike Doss and Nick Harper. Freeney, meanwhile, demonstrated the ability to be a special player.

On offense, Dungy asked for more of the same from Manning and Harrison, both of whom had Pro Bowl seasons. The line received a boost from draftee Steve Sciullo, while rookie tight end Dallas Clark was added to provide another threat in the passing game.

The central question focused on Edgerrin: Could he return to his all-star form? He swore he would, claiming his down year in 2002 had more to do with his gimpy ankles and ribs than his surgically repaired left knee.

Early in the season he was true to his word. Through three weeks, James had 263 yards on the ground, and the Colts were 3-0. But their hot start was due mostly to improved play on defense. Dungys troops clearly understood the coachs system better, particularly Thornton, who was making tackles all over the field. In the secondary, Doss was adjusting well at strong safety.

The offense kicked it into high gear in Week 4 with a 55-21 drubbing of the Saints in New Orleans. The Colts won the following week too, posting a stunning 38-35 comeback victory over the Bucs on Monday Night Football. Making those scoring outbursts all the most amazing was the fact that Edgerrin didnt suit up for either one. This time a bad back was keeping him out of the lineup.

When he returned to the action against Houston, Edgerrin seemed to have his old swagger back. While he wasnt breaking big runs, he was picking up tough inside yards, and in turn giving Indy greater balance on offense. With Manning settling into a good groove and Harrison enjoying another Pro Bowl campaign, the Colts re-established themselves as a force in the AFC.

In November, Indy started to think about both a division crown and homefield advantage in the playoffs. With the Patriots also on a roll, however, the team had little margin for error. When the Colts fell to New England in the RCA Dome, they saw their best chance for the top seed in the conference slip away. But Indianapolis responded the following week with an important victory over the Titans, putting the club on the inside track for the AFC South title. The Colts wound up with a record of 12-4, good for first in the division but not a first-round bye.

By then, Edgerrin was in peak form. With 108 yards and two touchdowns in Week 12, he was the difference in a 17-14 win over the Bills. Against the Falcons on the turf in Atlanta, he surpassed the century mark rushing for one of six times on the year. That effort included a 43-yard run, his longest of the season. On the campaigns final Sunday, Edgerrin amassed 171 yards against the Texans.

His fine performance continued into the post-season. Hosting Denver to open the playoffs, the Colts stampeded the Broncos in a 41-10 blowout. Manning was the star with 377 yards and five scores, but Edgerrin also pulled his weight, racking up 78 yards on 17 carries. If the game hadnt been over at halftime, he would have assumed an even bigger role.

That was evident a week later against the Chiefs in Kansas City. In a thrilling seesaw battle, the Colts emerged with a 38-31 victory. Again Manning hogged most of the headlines, passing for 304 yards and three touchdowns. Lost in the shuffle was Edgerrins outstanding production. Early in the contest, with the Chiefs geared to stop the Indy passing game, he exploited the KC defense with one strong run after another. His good work opened things up for Manning, who took it from there.

Indys march to the Super Bowl ended in the AFC Championship Game in New Englandthough through no fault of Edgerrins. In the 24-14 loss, he gained 78 yards, including a tough two-yard TD. Manning, however, was again bested by his nemesis, Bill Belichick. The Indy QB tossed four interceptions, two of which came in enemy territory.

For Edgerrin and the Colts, the 2004 campaign began in the same place that the '03 season had endedin New England against the Patriots. The game marked the kickoff of the '04 season, and was the marquee matchup of the week.

New England scored first on an Adam Vinatieri field goal, but then Edgerrin and the high-powered Colts got rolling and took a 17-13 lead into halftime. Unfortunately for Indy, Tom Brady heated up in the second half, en route to a 27-24 victory. Edgerrin had a good game, rushing for a 142 yards, but fumbled on the goal line with 3:43 left.

The following week the Colts traveled to Tennessee and got their first win of the season. The victory prompted a four-game winning streak. Edgerrin led the team in rushing in each contest, including 136 yards and a TD in a 35-14 laugher over the Raiders.

After back-to-back losses to Jacksonville and Kansas City, the Indy offense got rolling again. In winning eight in a row, the Colts averaged a whopping 36.3 points per game. Edgerrin ran for over 100 yards in five of the victoriesincluding a season-high 204 yards against the Bears. By now, however, he was being overshadowed by Manning, who was enjoying a season for the ages. Indeed, the seventh-year QB was on pace to break Dan Marinos formerly untouchable record of 48 TD passes. He threw for 27 scores during Indy's eight-game victory streak, including #49 in an OT win over the Chargers.

The Colts clinched the third seed in the powerful AFC with one game remaining, so Dungy rested several of his key regulars in the finale in Denver, including Edgerrin. When the Broncos won 33-14, they set up a playoff rematch the following week at the RCA Dome. For Denver fans, the results were eerily familiar. Edgerrin and the Colts exploded on offense, crushing the Broncos, 49-24. Manning was again the star, passing for 360 yards in the first half alone. Edgerrin didn't have to do muchhe rushed for 63 yards and a TD.

The victory earned the Colts another shot at the Patriots in New England. With the home team depleted by injuries, many in the media viewed Indy as the favorite. After years of disappointment for Manning in Foxboro, they believed his time had come to beat Belichick.

As usual, however, the Pats found a way to throttle the Colts. New England dominated the line of scrimmage, forcing Indianapolis to abandon the running game. With Edgerrin a non-factor, Manning struggled to solve the Patriot defense. Indy kept it close in the first half, but just couldnt hold on. NE forced three turnovers, and the Colts dropped many more passes than that. Limiting Edgerrin to 39 yards on 14 carries, the Pats won easily, 20-3.

Overall, Edgerrin had an excellent year. He finished fourth in the NFL with 1,548 rushing yards, and his 2,031 total yards were good for second in the league behind Tiki Barber of the Giants. His timing couldn't have been better. Now a free agent, Edgerrins stock is as high as ever. The Colts obviously would love to keep him, but they're facing serious cap problems after signing Manning and Harrison to long-term extensions.

Once regarded with suspicion because of who he is and where he comes from, EJ is now respected because he has never forgotten these things. No matter where he ends up next year, two things seem certain, as long as he stays healthy: hell be extremely productive and extremely wealthy.

EDGERRIN THE PLAYER

From a physical standpoint, Edgerrin is the total package. At 6-0 and more than 210 pounds, he combines size and speed with a wonderful feel for the game. His running style is smooth and powerful, and his splendid vision enables him to see the entire field. He also has sure hands out of the backfield.

In his younger days, Edgerrin sought out contact, eager to bowl over defenders on his way down the field. But as hes aged, hes realized the wisdom of being more elusive and avoiding big hits. Given his laundry list of injuries, this well-reasoned strategy should serve to lengthen his career.

How long Edgerrin chooses to play is another matter entirely. When he broke into the NFL, he made his priorities clear, saying that his #1 goal in life was to have fun. Its not that Edgerrin didnt work hard at his craft, but his public pronouncements caused management and teammates to wonder about the sincerity of his commitment.

The good news is that Edgerrin has begun to change his tune. Playing for Dungy has revitalized him, and the thought of a career deep into his 30s has become much more appealing.