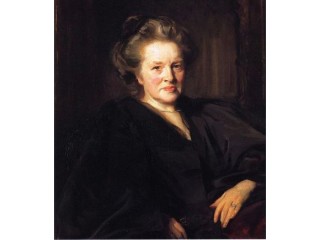

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson biography

Date of birth : 1836-06-09

Date of death : 1917-12-17

Birthplace : Whitechapel, London, England

Nationality : English

Category : Science and Technology

Last modified : 2011-03-25

Credited as : Physician, first female mayor in Britain,

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson was an english physician who was the first woman to qualify in medicine in Britain and who pioneered the professional education of women.

Elizabeth Garrett was the second of ten children (four sons and six daughters) born to Newson Garrett, a prosperous businessman of Aldeburgh, Suffolk, and his wife Louisa Dunnell Garrett. Believing that all his children—girls as well as boys—should receive the best education possible, Garrett's father saw to it that Elizabeth and her sister, Louie, were first taught at home by a governess. In 1849, they were sent to the Academy for the Daughters of Gentlemen, a boarding school in Blackheath run by the Misses Browning, aunts of poet Robert Browning. Garrett would later shudder when she recalled the "stupidity of the teachers," but the rule requiring students to speak French proved to be a great benefit. On her return to Aldeburgh two years later, she continued to study Latin and mathematics with her brothers' tutors. Garrett's friend, educator Emily Davies (1830-1921), encouraged her to reject the traditional and limited life of the well-to-do English lady. Davies believed that women should be given the opportunity to obtain a better education and prepare themselves for the professions, especially medicine. But Davies, who later became the principal of Girton College, Cambridge, did not feel suited to becoming a pioneer in the field of medicine and encouraged Garrett to take on this role.

Visiting her sister in London in 1859, Garrett met Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman in America to graduate from a regular medical school. Blackwell, who was then practicing medicine in England, had succeeded in having her name placed on the British Medical Register and was delivering a series of three lectures on "Medicine as a Profession for Ladies." Contrasting what she considered the useless life of the lady of leisure with the services women doctors could perform, Blackwell stressed the contributions female doctors could make by educating mothers on nutrition and child care, as well as working in hospitals, schools, prisons, and other institutions. Whereas Blackwell saw in Garrett a "bright intelligent young lady whose interest in the study of medicine was then aroused," Garrett had not yet decided on a career in medicine and was in fact somewhat overwhelmed by Blackwell's enthusiasm. "I remember feeling very much confounded," Garrett later explained, "and as if I had been suddenly thrust into work that was too big for me." Indeed, Garrett thought that she "had no particular genius for medicine or anything else." Nevertheless, Blackwell can be credited with having fueled Garrett's interest in becoming a fully accredited physician.

Despite his encouragement for his daughter to find some form of work outside the home, Garrett's father at first found the idea of a woman physician "disgusting." Her mother was too old-fashioned and inflexible to accept the idea that her daughter go to work, and she warned her family that if her daughter left home to earn a living, the disgrace would kill her. Seeking advice, Garrett was accompanied by her father on visits to prominent physicians; they were informed that it was useless for a woman to seek medical education because a woman's name would not be entered on the Medical Register, an official endorsement without which medicine could not be legally practiced in England. To guard against the circumstances that had made it possible for Blackwell to be entered on the register, foreign degrees had been ruled unacceptable. During their visits, one doctor asked Garrett why she was not willing to become a nurse instead of a doctor. "Because," she replied, "I prefer to earn a thousand rather than twenty pounds a year!" Indeed, throughout her life she remained vehemently opposed to the idea that women should be confined to nursing while men monopolized medicine and surgery.

Eventually, a meeting was arranged with Dr. William Hawes, a member of the board of directors of Middlesex Hospital, one of London's major teaching hospitals. This led to the suggestion that Garrett try a "trial marriage with the hospital" by working as a nurse for six months. Assigned to the surgical ward, she used the opportunity to attend dissections and operations, meet the medical staff of the hospital, and obtain some of the training provided to medical students. During this probationary period, Garrett found that she enjoyed the work immensely, that it was neither shocking nor repugnant to her feminine sensibilities, and that the difficulties against which she had been so seriously warned were quite trivial. "It is not true that there is anything disgusting in the study of the human body," she said. "If it were so, how could we look up to God as its maker and designer?" After a three-month probationary period, she abandoned the pretense of being a nurse and unofficially became a medical student, making rounds in the wards, working in the dispensary, and helping with emergency patients. She offered to pay the fees charged medical students but was told that no London medical school would admit her. The hospital staff accepted her as a guest, allowing her to study and carry out dissections, but would not accept her as a student.

In December of 1860, she took examinations that covered the work of the past five months and the results proved impressive. Then in May of the following year, she was accepted for some special courses of lectures and demonstrations; instead of providing new opportunities, this opening wedge stiffened the opposition and increased antifeminist hostility. When she received a certificate of honor in each of the subjects covered by her lecture courses, the examiner sent her a note: "May I entreat you to use every precaution in keeping this a secret from the students." When she answered a question in class that no other student could answer, the students drew up a petition calling for her exclusion on the grounds that she was interfering with their progress. The Medical Committee of Middlesex Hospital was glad to follow their recommendation and she left the hospital in July.

Despite further rejections from Oxford, Cambridge, and the University of London which, according to its charter provided education for "all classes and denominations without distinction whatsoever," Garrett would not be deterred. In 1862 the senate of the University of London had decided, however, that women were neither a class nor a denomination, which left the University without the power to admit them. Determined to secure a qualifying diploma in order to place her name on the Medical Register, she decided to pursue the degree of Licentiate of the Society of Apothecaries (L.S.A.); though the L.S.A. was not as prestigious as the M.D., its holders were duly accredited physicians. To qualify, an applicant had to serve a five-year apprenticeship under a qualified doctor, take certain prescribed lecture courses from recognized university tutors, and pass the qualifying examination. The Hall of Apothecaries was by no means an advocate of equal opportunity for women, but its charter stated that it would examine "all persons" who had satisfied the regulations, and—according to legal opinions obtained by Garrett's father—"persons" included women. An apothecary and resident medical officer at the Middlesex Hospital, who had been one of her tutors, accepted Garrett as an apprentice.

In October 1862, Garrett went to St. Andrews in Scotland where Dr. Day, the Regius Professor of Medicine, had invited her to attend his lectures. When university officials discovered that she had been permitted to secure a matriculation "ticket," the clerk was instructed to reclaim it. Garrett's refusal to return the ticket nearly sparked a lawsuit. It was finally decided that the university's constitution permitted the admission of women, but that the senatus had the discretionary power to exclude any particular person, male or female. Garrett was thus excluded. She remained in St. Andrews attending courses until December but had no chance of completing her studies there. Study in America might have been a possibility, but Garrett believed that her main task was to open the medical profession and medical education to women in England—even if the battle consumed much of her life and delayed her own career.

With great difficulty, she was able to piece together the elements of a course of instruction, including a summer spent studying with Sir James Simpson in Edinburgh and a very unhappy six-month period of service as a nurse in the London Hospital. But when Garrett presented her credentials to the Society of Apothecaries in the fall of 1865, the examining body refused to administer the examination. After Garrett's father threatened to sue, the apothecaries again reversed themselves. She passed the qualifying examinations to see her name enrolled in the Medical Register one year later. The Society of Apothecaries immediately revised their charter to require graduation from an accredited medical school—all of which excluded women—as a prerequisite for the L.S.A. degree. Another woman's name would not be added to the Medical Register for the next 12 years.

Garrett's goal was to establish a hospital for women staffed by women. Thus in 1866, she opened the St. Mary's Dispensary for Women in London "to enable women to obtain medical and surgical treatment from qualified medical practitioners of their own sex." For some years, she remained the only visiting physician and dispenser; three times a week, she attended outpatients, while also visiting patients in their own homes. The dispensary filled a great need; within only a few weeks, 60 to 90 women and children were seen each consulting afternoon. Serving an impoverished community as physician, surgeon, pharmacist, nurse, midwife, counselor, and clerk, Garrett's association with poverty-stricken families led to her involvement with the women's rights movement. In 1872, with a ward of ten beds, the dispensary became the New Hospital for Women and Children. Demand rapidly outgrew the original facilities, and three houses were purchased and converted into additional wards.

Like her friend Emily Davies, Garrett maintained a strong interest in the reform of education and the expansion of educational opportunities for women. At the time, free compulsory education was becoming a reality for the children of the working class, and Garrett was asked to run for election to the school board by the working men of the district in which she practiced. She was elected to the London School Board in 1870, the same year she obtained the M.D. degree from the University of Paris. Commuting back and forth from London to Paris, she passed all five parts of the examination and successfully defended a thesis on "Migraine" which showed her to be an excellent clinical observer who had treated a large number of patients suffering from migraine and other kinds of headache.

In 1869, Garrett applied for a staff position at the Shadwell Hospital for Children. James George Skelton Anderson, head of a large shipping firm, was one of the members of the hospital board of directors who interviewed her; he and Garrett began working together on reforms needed to improve the administration of the hospital. Their engagement was announced in December 1870. They were married on February 9, 1871.

Garrett continued to practice medicine, contrary to the common expectation for married women. Like Garrett's father, Anderson supported his wife's commitment to combine marriage and family with a medical career. Three children were born during their first seven years of married life, two of whom, Louisa and Alan, went on to distinguished careers of their own. The second daughter Margaret, however, died of tubercular peritonitis when only 15 months old.

The New Hospital for Women provided a demonstration of what trained professional women could accomplish. "No men or no hospital" served as Garrett's primary rule in guiding its development. In 1878, she became the first woman in Europe to successfully perform the operation of ovariotomy. Regarded as serious and dangerous, the first operation could not be performed in the hospital since the death of a patient would obviously injure its reputation. To deal with this problem, Garrett rented part of a private house and had the rooms thoroughly cleaned, painted, and whitewashed before the patient and nurses were brought in. The cost of the rooms and their preparation was contributed by James Anderson, who was proud of his wife's success but who noted, "We shall be in the bankruptcy court if Elizabeth's surgical practice increases." The next ovariotomy was performed in the hospital. Despite her successes, Garrett did not enjoy operating and was perfectly willing to turn this part of hospital work over to other skilled women surgeons as they joined her staff. The hospital moved to larger quarters at a new site in 1899, nearly two decades before being renamed the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital.

In 1874, along with Sophia Jex-Blake and others, Garrett helped establish the London Medical College for Women, where she taught for 23 years. As dean of the institution (1883-1903), she opposed the idea that women planning work as missionaries should come to the school and acquire a little medical knowledge. She "distrusted the capacity of most people to be efficient in two professions." Two years after its establishment, the London School of Medicine for Women was placed on the list of recognized medical schools, ensuring its graduates access to a registrable license. In 1877, the school was attached to the Royal Free Hospital and permitted to grant the degrees that were required for enrollment on the British Medical Registry. Garrett's son Alan was born just before the Royal Free Hospital opened its wards to women students; 50 years later he would become its chairman. The school became one of the colleges of the newly constituted University of London in 1901, and two years later, at the age of 67, Garrett resigned as dean to be appointed honorary president.

Whereas in controversial matters she took a quiet, professional position, Garrett was a suffragist and a member of the Women's Social and Political Union (founded 1903). Although she disagreed with women who were protesting against the Contagious Diseases Acts, which were instituted as an attempt to control venereal diseases, she was devoted to rebutting the pseudoscientific charge that intellectual activity harmed women's health and fertility; she was, regardless, condemned by some feminists for supporting the Contagious Disease Acts. Garrett's daughter suggests that her mother's training had provided little information about the venereal diseases and that her experience did not incite her to challenge the views of the medical profession in this particular matter. Later, the feminists were vindicated by evidence that the Acts were quite ineffective for their stated goals and offensive to many; they were repealed in 1886.

"Inadvertently" admitted to membership by the Paddington Branch (London) of the British Medical Association in 1873, Garrett was scheduled to read a paper on obstetrical section in 1875 at the annual meeting in Edinburgh when the error became known to Sir Robert Christison, then president of the association. Sir Robert proved unable to annul or expel Garrett, who was able to read her paper, but he and the association took steps to make sure no other women gained membership. A clause excluding females was added to the articles of the association in 1878, a prohibition not repealed until 1892. The only woman member of the association for 19 years, Garrett was elected president of the East Anglian branch of the British Medical Association in 1897.

In 1902 the Andersons retired to the Garrett family home in Aldeburgh, and six years later she became the first woman mayor of Aldeburgh. At the start of World War I, she traveled back to London to see her daughters Dr. Louisa Garrett Anderson and Dr. Flora Murray leave the city in charge of the first unit of medical women for service in France. "My dears," she said, "if you go, and if you succeed, you will put forward the women's cause by thirty years." During the war, Louisa Garrett Anderson was joint organizer of the women's hospital corps and served as chief surgeon of the military hospital at Endell Street from 1915-1918.

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson had lived a life full of firsts. She was England's first woman doctor, the first woman M.D. in France, the first woman member of the British Medical Association, the first woman dean of a medical school, and Britain's first woman mayor. Years after her death at Aldeburgh on December 17, 1917.