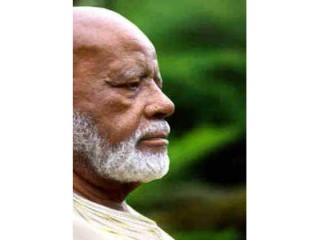

Ezekiel Mphahlele biography

Date of birth : 1919-12-19

Date of death : 2008-10-27

Birthplace : South Africa

Nationality : South African

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2011-04-20

Credited as : Writer and scholar, ,

Ezekiel Mphahlele is an acknowledged scholar on African literature. His works have been regarded as the most balanced of African literature.

"A writer who has been regarded as the most balanced literary critic of African literature," Ezekiel Mphahlele can also "be acknowledged as one of its most significant creators," writes Emile Snyder in the Saturday Review. Mphahlele's transition from life in the slums of South Africa to life as one of Africa's foremost writers was an odyssey of struggle both intellectually and politically. He trained as a teacher in South Africa but was banned from the classroom in 1952 as a result of his protest of the segregationist Bantu Education Act. Although he later returned to teaching, Mphahlele first turned to journalism, criticism, fiction, and essay writing. Mphahlele is acknowledged as one of the leading scholars on African literature.

During an exile that took him to France and the United States, Mphahlele was away from Africa from over a decade. Nevertheless, "no other author has ever earned the right to so much of Africa as has Ezekiel Mphahlele," says John Thompson in the New York Review of Books. "In the English language, he established the strength of African literature in our time." Some critics, however, feel that Mphahlele's absence from his homeland has harmed his work by separating him from its subject. Ursula A. Barnett, writing in the conclusion of her 1976 biography Ezekiel Mphahlele, asserts that Mphahlele's "creative talent can probably gain its full potential only if he returns to South Africa and resumes his function of teaching his discipline in his own setting, and of encouraging the different elements in South Africa to combine and interchange in producing a modern indigenous literature."

Mphahlele himself has agreed with this assessment, for after being officially silenced by the government of his homeland and living in self-imposed exile for twenty years, Mphahlele returned to South Africa in 1977. "I want to be part of the renaissance that is happening in the thinking of my people," he commented. "I see education as playing a vital role in personal growth and in institutionalizing a way of life that a people chooses as its highest ideal. For the older people, it is a way of reestablishing the values they had to suspend along the way because of the force of political conditions. Another reason for returning, connected with the first, is that this is my ancestral home. An African cares very much where he dies and is buried. But I have not come to die. I want to reconnect with my ancestors while I am still active. I am also a captive of place, of setting. As long as I was abroad I continued to write on the South African scene. There is a force I call the tyranny of place; the kind of unrelenting hold a place has on a person that gives him the motivation to write and a style. The American setting in which I lived for nine years was too fragmented to give me these. I could only identify emotionally and intellectually with the African-American segment, which was not enough. Here I can feel the ancestral Presence. I know now what Vinoba Bhave of India meant when he said: 'Though action rages without, the heart can be tuned to produce unbroken music,' at this very hour when pain is raging and throbbing everywhere in African communities living in this country."

His 1988 publication Renewal Time, contains stories he published previously as well as an autobiographical afterword on his return to South Africa and a section from Afrika My Music, his 1984 autobiography. Stories like "Mrs. Plum" and "The Living and the Dead" have received praise by critics reviewing Mphahlele's work. Charles R. Larson, reviewing the work in the Washington Post Book World, says that the stories in the book present "almost ironic images of racial tension under apartheid." He cites "Mrs. Plum" as "the gem of this volume." The story is a first-person narrative by a black South African servant girl, and through her words, says Larson, "Mphahlele creates the most devastating picture of a liberal South African white."

Chirundu, Mphahlele's first novel since his return to South Africa, "tells with quiet assurance this story of a man divided," says Rose Moss in a World Literature Today review. The novel "is clearly this writer's major work of fiction and, I suppose, in one sense, an oblique commentary on his own years of exile," observes Larson in an article for World Literature Today. Moss finds that in his story of a man torn between African tradition and English law, "the timbre of Mphahlele's own vision is not always clear"; nevertheless, the critic admits that "in the main his story presents the confused and wordless heart of his charcter with un-pretentious mastery." "Chirundu is that rare breed of fiction—a novel of ideas, and a moving one at that," says Larson. "It has the capacity to involve the reader both intellectually and emotionally." The critic concludes by calling the work "the most satisfying African novel of the past several years."

On the subject of writing, Mphahlele commented: "In Southern Africa, the black writer talks best about the ghetto life he knows; the white writer about his own ghetto life. We see each other, black and white, as it were through a keyhole. Race relations are a major experience and concern for the writer. They are his constant beat. It is unfortunate no one can ever think it is healthy both mentally and physically to keep hacking at the social structure in overcharged language. A language that burns and brands, scorches and scalds. Language that is a machete with a double edge—the one sharp, the other blunt, the one cutting, the other breaking. And yet there are levels of specifically black drama in the ghettoes that I cannot afford to ignore. I have got to stay with it. I bleed inside. My people bleed. But I must stay with it."