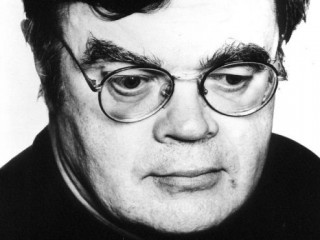

Garrison Keillor biography

Date of birth : 1942-08-07

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Anoka, Minnesota

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2011-05-12

Credited as : Author and radio personality, A Prairie Home Companion,

Garrison Keillor, host of public radio's popular A Prairie Home Companion and author of the best-selling Lake Wobegon Days, has made a career of telling stories about the fictional Minnesota town of Lake Wobegon and the lives of its residents. Keillor has become an American icon, and his show is heard by nearly three million U.S. listeners each week on over 500 public radio stations. It is also heard overseas on America One and the Armed Forces Networks in Europe and the Far East.

Author and radio personality Garrison Keillor writes about God's Frozen People, the Scandinavian settlers of the American Midwest, a quirky cast of characters united only by their religious faith and distrust of worldliness. After decades on the air, Keillor's A Prairie Home Companion became a cultural guidepost; a cottage industry has grown around him, including a store in Minnesota's Mall of America devoted to his fictional hometown. The television program The Simpsons "once did dead-on parody of a Keillor monologue," explained Bill Virgin in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, adding that "the term 'Lake Wobegon effect' was coined for school test results that showed that all the students were, like those in Keillor's fictional town, 'above average."'

Keillor was born Gary Edward Keillor in Anoka, Minnesota, on August 7, 1942. His paternal ancestors came from Yorkshire, England, around 1770; his maternal grandfather left Scotland in 1906. The third of six children, Keillor was raised in a conservative religious household. His family belonged to the Plymouth Brethren sect, which frowned upon activities such as drinking, dancing, and singing. Television was banned in the Keillor home. "[W]e were not allowed to go to movies because they glorified worldliness," Keillor told Associated Press reporter Jeff Baenen. " People drank in movies. They drank like fish. They smoked cigarettes. They danced. And we did not do those things." Radio, however, was allowed because "I don't think people smoked as much on radio."

Despite the strictures in his home, Keillor harbored lofty literary ambitions from a young age. At age 11 he started a newspaper called The Sunnyvale Star. In junior high, he submitted poems to the school paper under the pseudonym "Garrison Edwards," which he considered more grandiose than his given name Gary. He also developed a taste for the erudite New Yorker, which he discovered at the public library. "'My people weren't much for literature,"' Jay Nordlinger quoted Keillor as saying in the National Review, "so for him the magazine was 'a fabulous sight, an immense, glittering ocean liner off the coast of Minnesota."' Adopting as his life dream to work at the New Yorker, Keillor graduated from Anoka High School in 1960 and received his B.A. in English from the University of Minnesota in 1966. In college he worked at the Minnesota Daily and at the University radio station, KUOM, two extracurricular activities that ultimately helped his career.

After college, Keillor embarked on a month-long job hunt among magazines and publishing houses on the East Coast. He had interviews at the Atlantic Monthly in Boston and at the New Yorker and Sports Illustrated in New York. Keillor told Atlantic Unbound interviewer Katie Bolick that the trip convinced him, ironically, that where he really

wanted to work was in the Midwest. "If I had really wanted to get a job in New York, or course, I would have simply moved there and taken any job I could get and hoped for something better eventually," Keillor explained. "But I didn't: I was engaged to marry a girl who didn't want to move to New York, and I could see that New York is a tough place to be poor in, and then, too, I thought of myself as a Midwestern writer. The people I wanted to write for were back in Minnesota. So I went home."

In 1969 Keillor landed a job at Minnesota Public Radio that evolved into a career. At the same time, he took writing stints, and while researching an article for the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville, developed the idea for a radio show with musical guests and commercials for imaginary products. In the summer of 1974, he hosted the first broadcast of A Prairie Home Companion, which takes its name from a cemetery at Macalester College in St. Paul, Minnesota. In 1978 the show moved to its present broadcast site at the World (now Fitzgerald) Theater in Saint Paul and two years later began national broadcasts. In 1996 the show began broadcasting live over the Internet and direct to worldwide satellite. From its humble beginnings at a college auditorium, the show has played in well-known venues such as Radio City Music Hall, the Hollywood Bowl, and the Fox in Atlanta.

A Prairie Home Companion is a serial about the fictional town of Lake Wobegon and its inhabitants. Keillor described Lake Wobegon, population 942, as "the town that time forgot and decades cannot improve." The show celebrates small-town values in what Washington Post reporter David Segal described as "a seamless and enchanting two-hour variety program of homilies, comedy and music." The show consists of various segments, including news, comedy sketches, and fake commercials for sponsors like Ralph's Pretty Good Grocery Store ("Remember, if you can't find it at Ralph's, you can probably get along without it"). But the centerpiece of each show is always a 20-minute monologue, done by Keillor himself. "For me, the monologue was the favorite thing I had done in radio," Keillor told New York Times reviewer Mervyn Rothstein. "It was based on writing, but in the end it was radio, it was standing up and leaning forward into the dark and talking, letting words come out of you."

In 1985 Keillor married second wife Ulla Skärved, who had been a Danish exchange student at Anoka High and whom he met again at his 25th high school reunion. By 1987 Keillor quit A Prairie Home Companion—from "sheer exhaustion," he explained on the show's Web site—and moved to Denmark. However, within two years he had returned to the United States and started a new radio show in New York City. The show, American Radio Company of the Air, first broadcast in 1989 from the Majestic Theater in Brooklyn. It strongly resembled A Prairie Home Companion; so strongly in fact that in 1993 Keillor decided to revive the show back home to St. Paul.

Alongside his work as a radio personality, Keillor carried on a parallel life as a writer. After sending stories to the New Yorker for several years, he had his first story accepted for publication in 1969 and went on to become a regular contributor at his favorite magazine. In the early years writing for the New Yorker he lived with his wife and son Jason on a farm near Freeport, Minnesota, and would send two or three stories to his editor each month. But everything changed in 1992 when Tina Brown became editor of the magazine, replacing the legendary William Shawn. She introduced big changes to the magazine, which including phasing out a lot of the old writers. Keillor was one of the casualties of the new order, an event he recalls bitterly. "The New Yorker used to be a writers' magazine and it was very important to me," he told Irish Times contributor Frank McNally. "But under Tina Brown's editorship, it's been transformed into a magazine … driven by gossip. It's not a writer's magazine any more—it's all about 'buzz' now."

After his tenure at the New Yorker ended, Keillor started writing novels and in 1985 published the best-selling Lake Wobegon Days. Drawing on the same material he used for his radio show, Keillor spins tales of family life, school days, and growing up in the fictional small town of Lake Wobegon. Many of the stories describe the town's history and social conventions. It was the beginning of a literary phenomenon, as the book spawned a number of sequels and spin-offs.

In 1998 he published Wobegon Boy, a novel about John Tollefson, a radio manager stuck in a mid-life crisis. While some reviewers have compared Keillor to American humorists like Mark Twain and Will Rogers, National Review critic E. V. Kontorovich compared the author to Thomas Jefferson, noting that both rely on common-sense morality. "The antidote to self-absorption, self-pity, and other manifestations of the 12-step society can be found among the unpretentious Norwegian townsmen," asserted Kontorovich. "The reader will smile for as long as it takes him to read three hundred pages."

In 1998, at the age of 55, Keillor had a daughter Maia, with his third wife, violinist Jenny Lind Nilsson. Keillor's first son, Jason Keillor, from his marriage to Mary C. Guntzel, grew up to work as stage manager on his father's radio show.

While most of his works center upon Lake Wobegon, Keillor dabbled in politics with 1999's Me: By Jimmy "Big Boy" Valente as Told to Garrison Keillor, a satirical spoof about then-newly elected Minnesota governor and former wrestler Jesse Ventura. That same year he was awarded a National Humanities medal and was honored at a White House dinner hosted by President Bill Clinton. Explaining the selection of recipients, William R. Ferris, chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities, said "They are gifted people with extraordinary powers of creativity and vision, and their work in preserving, interpreting and expanding the nation's cultural heritage."

In 2001 Keillor published Lake Wobegon Summer 1956, a quasi-autobiographical coming-of-age tale. The novel's humor arises from the conflict between the protagonist's strict religious upbringing and his pent-up desires. New York Times reviewer Malcolm Jones found it only mildly amusing. "The same qualities that endear the show to us—its easygoing, deliberate corniness and amateurishness," wrote Jones, "suddenly seem merely cute, annoying and sometimes just plain trite on the page."

In July of 2001 Keillor underwent heart surgery at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. He made a full recovery and continued to broadcast his show and write. His books include story collections, novels, and children's books. In addition, he penned an occasional essay for Time and an advice column for the online magazine Salon and taught a writing class at the University of Minnesota. Keillor has considers his double-track existence satisfying both personally and socially. "Writing is pure entrepreneurship and a great way of life," he noted on the Prairie Home Companion Web site. "And then, if you do a radio show every Saturday, you have a built-in social life. So it's a pretty good deal."