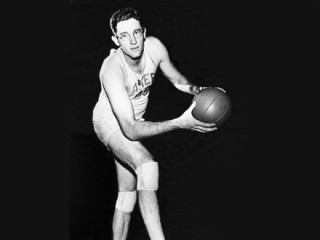

George Mikan biography

Date of birth : 1924-06-18

Date of death : 2005-06-01

Birthplace : Joliet, Illinois, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2010-08-05

Credited as : Basketball player NBA, played for the Chicago American Gears, and the Minneapolis Lakers

0 votes so far

George Lawrence Mikan, Jr. was born June 18, 1924, in Joliet, Illinois. His brother, Ed, came along 14 months later. The boys lived with their parents in a house behind the tavern their father, George Sr., owned. George learned the game practicing a rim attached to the garage. He would shoot by himself until his grandmother forced him inside to hone his skills on the piano. George was a big, athletic kid who played organized football and hockey. In 1934, he won the marbles championship of Will County, and earned free tickets to a White Sox game where he met Babe Ruth.

By age 13, George stood six feet tall and towered over his classmates. The target of taunts and teasing in his school, he was profoundly near-sighted, and wore thick glasses, even when competing in sports. To seem less tall, he perfected the fine art of slouching and slinking. One of the nuns at his school would smack him on the back whenever she caught him slumped over. “Straighten up,” she would shout. “The good lord gave you this body—make the most of it.”

While attending Joliet Catholic High, George badly broke a leg, an injury that kept him in bed for more than year. During that time he grew to 6-8. (Ed also eventually grew to 6-8, although at a more gradual pace.) George went out for Joliet's varsity basketball team as a freshman. Despite his size, he was told flatly by the coach that people with glasses could not play hoops.

George hit the baseball diamond in the summers, pitching and playing first base. One of his team’s regular opponents was the prison squad from Statesville Penitentiary. The inmates liked George so much they made him an eight-foot-long bed.

Intending to become a priest, George enrolled in Chicago’s Quigley Prep Seminary School as a sophomore, and gave up basketball. By the time he graduated in 1941, he decided to change course and study law. He really wanted to attend Notre Dame, and worked out for coach George Keogan. Keogan felt the youngster was too raw for the Fighting Irish, and advised him to enroll at a smaller school where his deficiencies would be less likely to be exposed.

George settled on DePaul University in 1941. He did not know how to tell his family that he had turned his back on the priesthood. The cat was let out of the bag when his father read in the sports section about the tall Mikan kid on DePaul’s freshman team. He figured the family had unknown relatives up in the Windy City until George finally came clean.

Big was about all George was at that point. First-year coach Ray Meyer inherited a raw talent and devoted himself to getting his project up to speed. After spring practice concluded, Meyer gave George a six-week crash course in basketball fundamentals, having him shoot hooks right- and left-handed. The coach made his prodigy go to dances each weekend and pair up with the smallest girls he could fine to improve his footwork. Meyer had George work a speed bag for hand quickness, and try shadow boxing and ballet classes. He also conceived something that the youngster would later perfect: The Mikan Drill. It involved taking short shots under the basket, alternating hands, as many as 300 in a single session.

Slowly but surely, George—who chose number 99 (now an illegal number)— developed agility and skills no other big man ever had. He wasn’t pretty, but he was effective. He did everything better than enemy centers, the point being he did everything—he was a complete player. And he refused to be muscled away from the basket. With no shot clock and a miniscule three-second lane, George was free to work his way methodically to the hoop, clearing his way with hard, sharp elbows, until he was in position to toss in a hook or layup. George score 10 points in his first varsity game for DePaul, in the fall of 1942. He was good for about that many each night the rest of the way.

While George’s offense took a while to develop, his defense was a factor right away. He had the timing and leaping ability to jump up and bat shots away just as they were heading into the basket. (This talent would lead the NCAA to institute the goaltending rule in 1944-45.) The Blue Demons went 19-5 in George’s first year on the varsity, and were invited to compete in the NCAA Tournament, which was still a poor sister to the National Invitation Tournament. They beat Dartmouth before losing to Georgetown, 53-49.

In 1943-44, DePaul went 22-4 and finished the year ranked fourth in the nation. George led the country with a 23.9 average and earned All-America honors. The Blue Demons went to the NIT and won twice before bowing out against Bob Kurland, the country's other dominant big man, and Oklahoma State.

No longer allowed to goaltend in 1944-45, George again topped the nation in scoring, this time at 20.9 ppg. Again invited to the NIT, the Blue Demons were unstoppable. George poured in 53 in the semifinals against Rhode Island State—a 97-53 win—and then guided DePaul to national title, winning tournament MVP honors along the way. His 40 ppg average in the tournament is still an NIT record. After the season, George was a unanimous First-Team All-American.

George’s final varsity season at DePaul saw his scoring rise to 23.1 per game, once again the NCAA's best mark. He also earned All-American honors for the second times. Anyone wondering who was the biggest star in college basketball had only to look at the attendance at a double-header that season held in Chicago Stadium. Almost 23,000 fans paid their way into the event, which touted DePaul vs. Notre Dame as its feature contest. The Blue Demons won 63-47, and ended the year 19-5, ranked fifth in the country.

With the war over and life returning to normal in the U.S., team sports entered a boom period. Pro basketball, a fly-by-night affair for most of its existence, was now pulling large enough crowds to be a viable business, especially with drawing cards like George. The National Basketball League, in its ninth year, decided to make him the highest paid player in the sport, as Maurice White’s Chicago American Gears (many pro teams in the '40s were owned by defense-related manufacturers) signed him for $60,000 for five years. The NBL, in competition with other leagues, instantly vaulted to the top of the heap.

George joined the Gears for the 1946-47 season. His first five games for Chicago actually took place in the World Professional Basketball tournament, which matched the best clubs against one another each year. Some clubs were league teams, like the Gears, and others were barnstorming teams, like the Harlem Globetrottters, who played serious ball in this tourney. With George netting 100 points against the top pros, the Gears captured the title.

Chicago went on to win the NBL championship, too, as George led the league in scoring at 16.5 ppg. The Gears outdrew the Stags, the other pro team in Chicago, which starred Max Zaslofsky, a huge name at the time. The Stags were part of the newly formed Basketball Association of America, the forerunner of the NBA.

White saw in his dominant center a chance to do something special. During the summer of 1947, he pulled out of the NBL, which included a lot of small-town teams, and formed his own league, the Professional Basketball League of America. With 24 franchises, the PBLA included much larger markets. On paper this looked like a no-lose deal, especially with George under contract at $12,000 a year. The Gears would generate large crowds in the Windy City, and collect a big cut for the sellouts their star attraction generated on the road.

Unfortunately, while this was a great opportunity for White, the other franchises would be left to fend for themselves. Also, the BAA already had teams in major east coast and midwest arenas. As the economic realities sunk in, White’s PBLA fell apart in November of 1947, before it ever played a game. When he applied to rejoin the NBL, he was flatly rejected. With no way to pay George, White had to release him from his contract. The best player in the game now a free agent.

With money in his pocket, and a lot more to come, George and his fiancee Patricia, decided to tie the knot. They would have six kids: Larry, Terry, Patrick, Michael, Trisha and Maureen.

The NBL, which had most of the pro game’s best players, did not want to lose George to the BAA. His rights belonged to the last-place Detroit Gems, who were purchased for $15,000 over the summer by Morris Chalfen and Ben Berger. The Gems came with no player contracts, so the two men had to start from scratch.

They moved the franchise to Minneapolis, where the NBL had staged games the previous season and received an enthusiastic welcome, and renamed the team the Lakers. George remembered the frigid nights in Minnesota from his college days, and was not inclined to make the Twin Cities area his home. When he learned the Lakers had his rights, he joked that he had been “drafted by Siberia.”

George was smart enough, however, to recognize that the Lakers were doing it right. They hired young John Kundla to coach the team. He had piloted St. Thomas College across the river in St. Paul, and recruited University of Minnesota stars Swede Carlson and Tony Jaros for Minneapolis. Next Chalfen and Berger inked Stanford superstar Jim Pollard, the best all-around college forward of the postwar years. Pollard, who signed for $12,000, forced the Lakers hire two of his Stanford teammates, who were not pro caliber.

George and his lawyer met with team representatives in Minneapolis. After a three-hour bargaining session, he was unconvinced and asked if someone could drive him to the airport. He was chauffered everywhere but the airport, arriving after the last plane for Chicago had left. The bargaining session restarted and by morning the Lakers had worn him down. George agreed to play for $12,0000 a year, and suited up for the teaqm five games into the schedule.

Thanks to their star-studded lineup, the Lakers developed a huge following in Minneapolis and St. Paul, playing home games in each city. With quality players surrounding him, George became a true superstar, taking charge at both ends of the court and creating offensive, defensive and rebounding opportunities for his fellow Lakers.

The Lakers finished far ahead of the second-place Tri-City Blackhawks in the Western Division, and then faced the Oskosh All-Stars in the first round of the playoffs. Minneapolis took the series in four games, setting up a best-of-three tilt with Tri-City. The Lakers disposed of the Blackhawks with back-to-back blowouts.

Next up were the Rochester Royals for the NBL championship. Again the Lakers were dominant. They claimed the title in four games.

During the off-season, the BAA set in motion a plan to absorb the NBL. The former had the best venues, while the latter had the best players. The BAA induced four “big-market” NBL cities to join its fold, and those teams—the Lakers, Royals, Ft. Wayne Pistons and Indianapolis Jets—just happened to have a slew of top talent, including Arnie Risen, Bob Davies, Bruce Hale and, of course, George and his teammates.

The Lakers and Royals renewed their rivalry in the BAA, controlling the Western Division. Rochester edged Minneapolis for first place, 45 wins to 44. George led the league in scoring at 28.3—a new record—finished second to Risen in field goal percentage at 41.6, shot 77 percent from the free throw line and had as many assists as fouls. He was a shoo-in for league MVP.

Minneapolis swept the Stags in the first round of the playoffs. On the Chicago roster, and guarding George, was his younger brother, Ed, in his first pro season after graduating from DePaul. This win set up a meeting with the Rochester. In a best-of-three showdown, the Lakers edged the Royals in Rochester, 80-79, and then demolished them in a contest at St. Paul to advance to the finals.

The Lakers made the most of their homecourt advantage in the best-of-seven series, taking Games 1 and 2 from the Washington Capitols, coached by Red Auerbach. Minneapolis beat the Caps by 20 in Game 3 in Washington, and looked good for the sweep in Game 4. Fortunes turned, however, when George fractured a wrist in a collision with Washington’s Kleggie Hermsen. He continued to play, despite grotesque swelling, but the Lakers could not close out the Caps. Washington took the next game, too, as George tried to get accustomed to the hard cast surrounding his injured joint.

By Game 6, played in St. Paul, George had figured out how to use the protective plaster as a bludgeon. He savaged Bones McKinney, netting 30 points in a 77-56 victory that gave the Lakers their second straight pro title. George averaged 30.3 points per game in the post-season to set a league mark.

In 1949, the NBL disintegrated, and the BAA absorbed the six remaining solvent franchises, including the Syracuse Nationals, who would evolve into the Philadelphia 76ers in 1963. The Nats went into the East, while the other five teams were dumped into a new Western Division along with the Jets. The Lakers moved to the Central with four other clubs. The league, meanwhile, changed its name to the National Basketball Association.

The rich got richer in the draft, too. The Lakers selected University of Texas point guard Slater Martin and a little-known local power forward named Vern Mikkelson. The two future Hall of Famers meshed easily with Pollard, Ferrin and the other Minneapolis stars. Bob Harrison and Bud Grant (future coach of the Minnesota Vikings) also joined the team as reserves, with Harrison earning plenty of minutes in the backcourt. The long-armed Mikan-Pollard-Mikkelson front line was the most awesome defensive unit in the new league.

The Lakers and Royals tied for the most wins in the NBA with 51, with Minneapolis winning a one-game playoff to determine the top seed in the post-season. George once again topped the NBA in scoring (27.4) and finished second to Dolph Schayes in rebounds, the first year the NBA listed this stat officially.

With George dropping in 30 a night, the Lakers swept the fourth-place Stags and manhandled the Pistons after they had shocked Rochester in the first round. In the NBA Finals, against the Nationals, George spearheaded three victories in the first four games. Minneapolis captured its third title in three years—in three leagues—by winning Game 6, 110-95. The point total, huge for this era, made headlines.

Indeed, early the next season the Lakers were involved in a game that saw a mere 37 points scored. In an attempt to keep the ball out of George’s hands, Ft. Wayne employed stall tactics and won 19-18. This strategy caused an outcry by fans, and deep concern on the part of the owners. The result of this sticky situation would be the introduction of the 24-second clock in 1954.

The shot clock was not the only Mikan-inspired innovation. His adeptness on defense in college had led to the modern goaltending rule, of course, but what is not widely known is that in March of 1954 the Lakers and Milwaukee Hawks were asked by the league to play a game with 12-foot baskets—specifically to curtail George’s dominance. The experiment failed when no one could hit an outside shot and George and teammate Clyde Lovellette were even more powerful in rebounding and inside scoring. Later, in 1951, the league widened the free throw lane from six to 12 feet to force George start his moves to the rim farther out.

The NBA owners may have tinkered with the pro game in response to George’s superiority, but they knew where their bread was buttered. In the days before the league became a marketing machine, George was their lone superstar player, and they made the most of it. In December of 1949, the Lakers had visited New York and the marquee at Madison Square Garden read: Tonite: Geo Mikan vs. Knicks. As George prepared for that game, his teammates staged a mock walkout, insisting that since they weren’t listed as playing the Knicks, they shouldn’t have to take the floor. In reality, they knew that he was the guy putting food on their tables. Frequently, he would be flown into a city a day before the rest of the team and hold newspaper and radio interviews pumping up the next night’s game.

Other than the fact that the league contracted from 17 to 11 teams, the 1950-51 campaign began no differently for the Lakers and the rest of the NBA. George was dominant (leading all scorers again with 28.4 ppg), the team won twice as often as it lost, and the regular season seemed like little more than a warm-up for the playoffs. George played in the first NBA All-Star Game, scoring 12 points and hauling down 11 rebounds in the West’s 111-94 loss to the East. In the middle of the campaign, he was voted the greatest basketball player of the first half-century.

Late in the year, George fractured an ankle and hobbled through the post-season. After defeating Indianapolis in the first round, the Lakers fell to Rochester, whose two stars, Davies and Risen, guided their team past the Knicks in the finals for the championship.

The Lakers bounced back the following year with another strong showing, and added valuable role players in Whitey Skooj and Frank Saul. But the league appeared to be catching up with Kundla’s squad. The Nationals, Knicks, Celtics and Royals all had quality clubs, and with George setting up an extra six feet from the basket, the Minneapolis offense was less intimidating than in years past. George’s average dropped to 23.8, and jump-shooting Paul Arizin edged him for the scoring title.

Rochester finished a game ahead of the Lakers, earning the homecourt nod when they met in the best-of-five West finals. Minneapolis, however, erased that advantage with a Game 2 victory in Rochester, and then mopped them up in the next two games in Minnesota.

Their opponent in the finals were the Knicks, led by guards Dick McGuire and Max Zaslofsky, and big men Sweetwater Clifton and Harry Gallatin. They attacked the Minneapolis front line at both ends during the best-of-seven series, which went the distance. The teams split the first two games in St. Paul and the next two at the Garden. With the Lakers restoring homecourt, they won Games 5 and 7 to reclaim the championship.

The 1952-53 season was a great one for the Lakers, and a good one for George, who became the first pro to grab 1,000 rebounds. He was also named MVP of the All-Star Game. George averaged 20.6 points to finish second in the league, but he was hacked more than usual, as many teams simply fouled him as soon as he got the ball in good position to bulldoze his way to the hoop. This was especially effective, because it meant only one free throw, as the rules stated at the time. With his inside game somewhat neutralized, George began experimenting with a jump shot.

The Lakers wound up with a league-high 48 wins, and throttled Indianapolis and Rochester in the West playoffs, dropping a total of one game. The Knicks, having added high-scoring rookie Carl Braun, repeated as East champs. They played their hearts out in the first two games in Minneapolis, winning the opener and losing Game 2 by a bucket.

Feeling George was lacking his usual fire, Kundla hired Ray Meyer as a bench coach in New York. Meyer scolded George at halftime for falling in love with his jumper and ordered him to return to his hook. He scored 30 after the intermission as the Lakers seized command of the series with a 90-75 victory. They finished off the series without having to leave Madison Square Garden, beating the Knicks in Games 4 and 5.

In the following season, for the first time since his rookie year, George, now 29 with aching knees, averaged less than 20 a game. Some of the scoring slack was taken up by “Cumulus” Clyde Lovellette, the looming first-year player from Kansas who was just a hair shorter than George. In addition, George did not lead the Lakers in minutes played. Still, he hauled down 1,026 rebounds, second in the league to Gallatin of the Knicks.

The Lakers once again turned in the NBA’s best record with 46 wins. They emerged from a weird round-robin playoff format (abandoned the following season) to meet Rochester for a shot at the finals. Minneapolis won both of its home games in the best-of-three clash, and met Syracuse for the NBA crown, as they had in 1950.

The Nats were led by the do-it-all Schayes and veteran guard Paul Seymour. The series see-sawed through six games, with the Lakers winning Game 1 and the teams alternating from there. Minneapolis kept this pattern going in Game 7 with an 87-80 victory for its third straight NBA crown.

George did not have much gas left in the tank, and with the coming of the 24 second clock, he knew the days of bruising halfcourt basketball would be ending soon. He had been taking law courses at DePaul in the off-season and now had his degree. Three days before training camp opened in 1954, George called it quits. The Lakers soldiered on without him, and Lovellette did a decent job filling his shoes. They finished with 40 wins, but fell to Ft. Wayne in the West finals on their own home floor.

In 1955-56, the Lakers began bottoming out. Pollard had retired and the rest of Kundla’s championship cast were lost without their two old stars. The team pleaded with George to return and promised him a role in management. He played in 37 games, averaging a little more than 10 pints and a little less than 20 minutes per contest. He could no longer jump, and muscled his way to most rebounds. Minneapolis went 34-38, and fell to the Hawks in an exciting first-round playoff meeting.

After the season, George retired for good. He left the game with the NBA records for most points (11,764) and the highest scoring average (23.1). George ran for Congress on the Republican ticket in 1956, got great support from President Eisenhower, but lost in a heavy Democratic district.

He took up the Lakers on their job offer and coached the team to a horrid 9-30 start in 1957-58 before stepping down and returning to his law practice. The reward for the team's miserable 19-53 record was the first pick in the 1958 draft. They selected a dynamic forward out of Seattle named Elgin Baylor. He gave the team an exciting new style that enabled them to survive tumbling attendance in Minneapolis and recreate themselves in Los Angeles in 1960. That was the year Jerry West joined the team out of West Virginia. Although the new Lakers would not reach the heights the old ones did, they were the best in the West during the Celtic dynasty of the 1960s.

Thanks to the big men that followed George (namely Bill Russell and Wilt Chamberlain), pro basketball gained enough of a foothold in the '60s to spawn a viable second league, the American Basketball Association. When ABA owners looked for a figurehead as league president, they hired George. His first move was to insist that the ABA use a red-white-and-blue basketball, which would become the single-most effective marketing piece the ABA ever had (and the thing most remembered about the league three decades later). Mikan served as ABA president for two seasons, and then went back to his law practice. He used his law background to push for better pension for pre-1965 players, though he never got the concessions from the league that he believed those from his era so richly deserved.

In 1970, his son, Larry, graduated from the University of Minnesota and played a year with the Cleveland Cavaliers during their inaugural 1970-71 season. After retiring from his practice in the 1980s, George continued to fight for players rights. His health began to fail in the 1990s, and his right leg was amputated as a result of a rapidly progressing diabetic condition. In 2001, outside the Target Center, the Minnesota Timberwolves erected a statue of George firing his trademark hook shot. He passed away on June 6, 2005, a few days before he turned 81.

George’s legacy can be seen every time an NBA center takes a pass in the post. Before he came into the game, no one played above the rim. By the time he retired, the pro game was beginning to take wing. Six-ten players are a dime a dozen these days, but none dominate the way George did. How did he compare to the other centers of his era? Think Yao Ming with a sky hook, 50 more pounds of muscle, a bad attitude…and bottle-bottom glasses.

The Mikan Drill, by the way, is still used at every level of basketball, from high school to the pros.