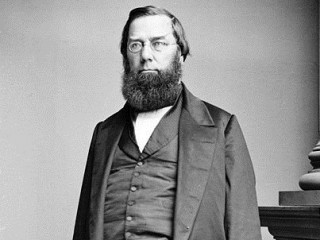

George Perkins Marsh biography

Date of birth : 1801-03-15

Date of death : 1882-07-23

Birthplace : Woodstock, Vermont, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Science and Technology

Last modified : 2011-05-16

Credited as : Diplomat and philologist, The Earth as Modified by Human Action,

George Perkins Marsh is best remembered for his work Man and Nature (1864), which was later revised as The Earth as Modified by Human Action (1874). Published one hundred years before the ecology movement of the 1960s, Marsh's theories recognized human impact on the environment and have since influenced ecologists throughout the world. A skilled diplomat, Marsh is also acknowledged for his successful posts as ambassador to both Turkey and Italy.

Marsh was born in Woodstock, Vermont on March 15, 1801. He grew up in rural Vermont and maintained an affinity with the outdoors throughout his life. Marsh's ancestors on both his paternal and maternal side included members of the intellectual elite of New England. His father, Charles Marsh, a prominent local lawyer and district attorney for Vermont, established his estate in an idyllic setting along the Quechee River in the foothills of the Green Mountains. As David Lowenthal speculated in his biography George Perkins Marsh: Versatile Vermonter, this setting helped shape Marsh's ideals as "From the summit of Mt. Tom young George Marsh could survey the entire cosmos of his early years. The main range of the Green Mountains, far to the west, was dark with spruce and hemlock and white pine. But thirty years of clearing and planting had converted the lower, gentler hills surrounding Woodstock into a variegated pattern of field and pasture, while pioneer profligacy and the need for fuel had already destroyed much of the forest on the steeper slopes."

Much of Marsh's childhood, however, was spent indoors. He showed an early aptitude toward study, beginning to read Reese's Encyclopaedia at the age of five. Influenced by his strict Calvinist father, Marsh was infused with an almost compulsive need to acquire facts. According to Lowenthal, "His family considered him a paragon because he knew almost everything from ethics to needlework." In fact his devotion to reading reportedly led to poor eyesight, and at age seven or eight, he was restricted from reading for four years. During this time, young Marsh ventured out into the woods and began to observe nature firsthand. He commented that "the bubbling brook, the trees, the flowers, the wild animals were to me persons, not things." Marsh took not only an aesthetic interest in nature, but, owing to his father's influence, a scientific interest as well.

Marsh gained much of his early education at home as his older brother taught him Latin and Greek, his father geography and morals, and he garnered a great deal of information from his own reading of the encyclopedia. However, because his father wanted young George to receive a more traditional and religious education, Marsh was sent to Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, in 1816. There amidst a "prison-like existence" Marsh failed to thrive intellectually. Within a few months, he had left Andover. At age fifteen, he attended Dartmouth College, although he had little fondness for the uninspired curriculum and took it upon himself to study Spanish, Portuguese, French, and Italian. Following his graduation at age nineteen, Marsh taught Greek and Latin at Norwich Academy. He detested teaching and quit after just one year.

During the next four years, Marsh returned to Woodstock, where he recovered from a relapse of the eyesight condition he had suffered from as a child. He also began to study law and, in 1825, was admitted to the bar. He then moved to Burlington, Vermont, where he lived for 35 years, pursuing his legal career as well as numerous unsuccessful business ventures. Never truly happy as a lawyer, Marsh ran for Congress as a Whig and was elected in 1843. He served until 1849. During his tenure in office, Marsh opposed the admission of Texas as a slave state and argued against United States involvement in the Mexican War. Perhaps Marsh's most lasting legacy in Congress, however, was his involvement in organizing the Smithsonian Institute. In Lowenthal's biography of Marsh, he contended, "The Smithsonian story illustrates the kind of role that Marsh was to play again and again. He was not a great statesman. Nor was he a scientist of the first rank; he made no original discoveries. But in the borderlands linking science and the public weal Marsh made lasting contributions. He applied science to life, not with the disinterested precision of an engineer, but with the aims and methods of a humanist. The Smithsonian—its aims, its activities, its personnel—was in large measure the result of Marsh's efforts as an impresario of ideas."

Marsh was appointed United States minister to Turkey in 1849 by President Zachary Taylor. Marsh's proficiency in 20 languages helped distinguish him as a highly effective diplomat. In addition to his duties as minister, Marsh traveled extensively and furthered his interest in the study of geography. He gathered meteorological data that he compiled in writing pieces for the American Journal of Science, as well as collecting plant and animal specimens that he sent to the Smithsonian. Following an administration change, Marsh was recalled to the United States in 1854 and served as Vermont railroad commissioner from 1857 until 1859. Also upon his return, Marsh began to garner recognition as an eminent philologist, lecturing at Columbia University and the Lowell Institute. His A Compendious Grammar of the Old-Northern or Icelandic Language (1838), Lectures on the English Language (1860), and The Origin and History of the English Language (1862), while ponderous and outdated are nevertheless considered important works in the field of philology.

In 1861, Marsh was appointed by President Lincoln to be the first United States minister to the new kingdom of Italy. He successfully held this post for the last 21 years of his life. So well trusted was Marsh that the Italian government allowed him to arbitrate a difficult boundary dispute between Switzerland and Italy. Having served longer than any American diplomat except Benjamin Franklin, Marsh became known as the "Patriarch of American Diplomacy." Marsh died in Vallombrosa, Italy, on July 23, 1882 and was buried in Rome. His various accomplishments as a scholar and diplomat earned him accolades, prompting this description in American Authors: 1600-1900: A Biographical Dictionary of American Literature: "[He was] one of the most typical and most significant examples of the nineteenth century New England mind in action."