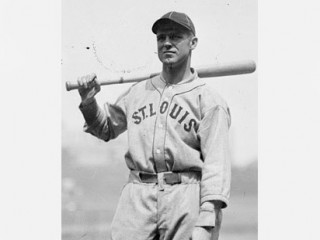

George Sisler biography

Date of birth : 1893-03-24

Date of death : 1973-03-26

Birthplace : Nimisila, Ohio, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2010-08-24

Credited as : Baseball player MBL, played for Michigan,

0 votes so far

George, a lefthander, took naturally to all athletic endeavors during his childhood, exhibiting great hand-eye coordination, balance and speed. Like most boys at the turn of the century, baseball was his favorite sport. When he wasn't playing, he was watching—his part of Ohio had many town, semipro and minor-league clubs.

At the age of 14 high school beckoned. Since Nimisila didn't offer much in the way of schoolboy sports, George transferred to the Akron school system. From 1908 to 1911, he pitched for Akron High and gained enough notoriety to attract the interest of the local pros. He also earned scholarship offers from a handful of colleges, including the University of Pennsylvania.

In 1911, prior to his 18th birthday, George became enamored of the idea of playing pro baseball. Though he signed a contract with the Akron Champs of the Ohio-Pennsylvania League, he received no money and never practiced or played a game with the club. Later that spring, at the urging of his father, George decided to accompany a high school teammate to the University of Michigan, where he was immediately recruited for the baseball team by a law student who also coached the squad. His name was Branch Rickey.

While at Michigan from 1911 to 1915, George earned a degree in mechanical engineering. Rickey, who left the school to manage in the major leagues in 1913, installed George in the outfield and at first base on days when he wasn't pitching. The coach who followed Rickey, Carl Lundgren, used him the same way.

Under Lundgren, who starred on the mound for three Chicago Cub pennant winners from 1906-08, George developed into the best all-around player in Michigan history. He went 13-3 as a varsity pitcher with more than 200 strikeouts, and batted .404 (129 for 297) for the Wolverines. Michigan did not compete in the Big Ten while he attended the school, so the quality of the competition may have been spotty. In one game, however,George fanned 20 batters in seven innings, an indication how much talent he possessed.

During his days in Ann Arbor, George had his contract assigned to Akron's parent club, Columbus, which sold it to the Pittsburgh Pirates. The Pirates were owned by shrewd and powerful Barney Dreyfuss, whose attempts to make George report went ignored. During the 1912 season, Dreyfuss brought the matter to the attention of the National Commission, then baseball's ruling body. The Commission, which found itself in a tricky situation, recognized that upholding the contract might compromise George's collegiate eligibility.

With Rickey and a Detroit judge named George Codd advising him, the young star sent a letter to the Commission pointing out that he was a minor when he signed the contract, and thus should not be considered the property of the Pirates or any other club. George's father wrote a letter confirming the fact that he had never given his permission for the contract to be signed. Dreyfuss countered that he had spent money on George's contract, and at the very least was due some form of compensation.

Over the next couple of years, the case dragged on. Cincinnati Reds owner Garry Herrmann, who chaired the National Commission, offered a compromise by which Sisler would become a free agent, but that he would be morally obligated to give Pittsburgh every opportunity to sign him. Codd refused. In the years since the controversy began, George had become the top college player in the nation, and there was no reason to limit his options

At one point, an unnamed owner suggested that George be granted his free agency, and that the other clubs simply agree that no one would sign him except the Pirates. With organized baseball anticipating court challenges from the newly formed Federal League, Dreyfuss felt this strategy to be unwise. During his senior year at Michigan, George was informed that he was an unrestricted free agent.

After graduating in June of 1915, George wired Dreyfuss that he would indeed give the Pirates every opportunity to sign him, and also informed the Pittsburgh owner that other teams had already expressed interest in him. Dreyfuss offered $700 a month, plus a $1,000 signing bonus, but he was outbid by the St. Louis Browns, who gave George a $5,000 bonus, a modest $400 salary, and a guarantee of a substantial raise the following year if he made good.

In reality, the Pirates were never in the running. Nor was anyone else, for that matter. The manager of the Browns was Rickey.

Dreyfuss smelled a rat and accused the Browns of tampering. He filed a complaint with the National Commission which, because it involved the rival leagues, had to be decided by Herrmann. The case, which Herrmann dismissed a year later, was a major nail in the coffin of the Commission, which had been beset by political wrangling since its inception more than a decade earlier. Many NL owners felt Herrmann was unduly influenced by the AL's dynamic president, Ban Johnson, and the Sisler decision only strengthened this conviction. In 1920, a majority group of owners disbanded the office and hired a full-time commissioner, Kenesaw Mountain Landis. By that time, Sisler had become a superstar.

George made his debut for the Browns on June 28, 1915, against the White Sox in Chicago. He entered the game in the top of the sixth inning as a pinch-hitter and stayed in to pitch three scoreless innings in a 4-2 loss. It was one of 91 defeats suffered by St. Louis that season. The Browns finished in the second division, well behind league powerhouses Boston, Detroit and Chicago.

George appeared in a total of 81 games during the 1915 campaign, 15 as a pitcher and the rest split between the outfield and first base. His average was .285, not bad for that era, with 15 extra-base hits and 10 stolen bases. Despite George's pitching prowess against college competition, Rickey had always suspected he would be no more than a serviceable major league hurler. His numbers were good as rookie—4-4 with a 2.83 ERA—but most important was that he showed he could handle the bat as well as any young hitter in the league.

Still, in 1915, George was regarded as a pitcher who could hit, not a hitter who could pitch. He twice beat Walter Johnson, one of his heroes as a boy, outdueling him 1-0 in their first meeting and 2-1 later that season. George also fanned nine Cleveland batters in a 3-1 victory over Guy Morton, one of the top hurlers of the day. By the end of the season, though, Rickey convinced George that his future was as an everyday player.

It wasn't just George's hitting that prompted the move. Almost upon his arrival in the majors, he added new dimension to the first base position. In a game against the Red Sox with none out and runners at first and third, leftfielder Burt Shotten caught a short fly moving to his left. He had already conceded the run, but noticed the other Boston runner taking his time getting back to first. Shotten rifled a ball to George, who decoyed the runner into an out. Then George, who noticed the runner at third jogging home, twirled and threw to catcher Hank Severeid to complete what must still be considered a unique triple play. A few years later, George charged toward home on a squeeze play, fielded the bunt and tagged the batter, then flipped to Severeid to get a tag-tag double play on a suicide squeeze—another remarkable accomplishment.

George's first full year in the majors found him the focal point of a ball club populated by journeyman such as Jimmy Austin, Ward Miller and Carl Weilman—a lot of names recognizable to fans then, though all but forgotten today. The team's stars were second baseman Del Pratt—one of the best middle infielders of the 'teens—and Shotten, whose knack for drawing walks and stealing bases made him an ideal leadoff man. Another speedy outfielder was Armando Marsans, one of the first Latino players in the majors and something of a hot dog.

Eddie Plank, pushing 40, was also on the team, closing in on 300 wins with his cross-fire curve. The future Hall of Famer was baseball's all-time winningest lefty in 1916. He had pitched for the St. Louis Terriers of the Federal League the year before, and was assigned to Browns when the Feds shut its doors at season's end. The Browns' new manager, Fielder Jones, also came over from the Terriers, supplanting George's friend, Rickey. Jones had taken a miserable Federal League club and guided it to within percentage points of the championship in 1915.

With Jones at the helm and George rapping out a team-high 177 hits, St. Louis had its first winning season since 1908. The young first baseman stole 34 bases, hit .305 and fielded his position with great aplomb, drawing comparisons to Hal Chase of the Reds. Pratt led the league in RBIs, Shotten drew an AL-best 110 bases on balls, and all five starters won in double figures. George got three spot starts, twirled three complete games, and fashioned a nifty 1.00 ERA. The Browns finished fifth, 12 games behind the Red Sox, who unlike St. Louis had chosen not to convert their young lefthanded pitcher, George Ruth, to an everyday player.

The next two years saw the Browns revert to their bad habits, with losing records in 1917 and 1918. Despite a pair of no-hitters by Ernie Koob and Bob Groom, the team's pitching gave way to age and injury, and the middle-of-the-pack offense could not pick up the slack. During these otherwise dismal seasons, George came into his own as a hitter. In 1917, he finished second to Cobb in the batting race with a .353 average and was among the league leaders in hits, doubles, stolen bases, total bases and slugging. At this point, he had settled into the third spot in the batting order, where he would remain for most of his career.

In 1918, George batted .341 and led the league with 45 steals. In the season's final game, he pitched an inning against the Tigers, who sent Cobb to the mound for two frames. George doubled off the Georgia Peach. Earlier in the year he broke up a no-hitter by Walter Johnson. It would seem that George owned the town in 1918, but the Cardinals had a young star named Rogers Hornsby who hit the ball with even more authority. Over the next few years, they would vie for supremacy in the Gateway City.

Fielder Jones got the ax after 46 games in 1918, and was ultimately replaced by Jimmy Burke, a respected St. Louis baseball man. In reality, it was a lost season for everyone around the game—teams were badly depleted by the draft and the schedule was severely shortened.

Burke piloted the club to another second-division finish in 1919, but the makings of a decent team were there. Outfielders Jack Tobin, Baby Doll Jacobson and Ken Williams were all entering their prime years, as was sparkplug shortstop Wally Gerber. Famous for letting his teammates pick up the check, Gerber got the last laugh many years later, when his fiduciary conservatism made him a wealthy man. Always a good teammate, he came to the aid of several down-and-out players. The team's rock-steady catcher was Hank Severeid, who became a regular for the Browns the same year as George. The St. Louis pitching staff was led by Allan Sothoron, a spitballer who turned in his one and only 20-win season, and Urban Shocker, picked up in a trade with the Yankees.

George topped the .350 mark again in 1919, this time with newfound power. He socked 31 doubles, 15 triples and 10 homers, and added 28 steals to become the only man in the majors to reach double-digits in all four categories.

The 1920 season welcomed an explosion of offense in baseball—thanks to hitter-friendly new baseball—and once again George reached double figures in doubles, triples, homers and steals. Ken Williams, injured the previous year, played his first full season for the Browns, and was the only other American Leaguer to turn the trick. In the shadow of Babe Ruth's monster year for the Yankees, George, now 27, blossomed into a great hitter in his own right.

Indeed, this was the season he set a new record with 257 hits. A line drive machine, George also led the AL with a .407 average. It had been eight years since an American Leaguer had hit .400. George's 19 home runs were matched by a mere 19 strikeouts—one of baseball's toughest feats in any era. He had one streak of 25 straight games with a hit, and also played every inning of every game.

The Browns continued to inch toward respectability, finishing a game under .500. Jacobson had a superb year with 216 hits and 122 RBIs, while Tobin topped 200 hits and batted a robust .341. Once again, pitching proved problematic. The new ball took some of the hop off Sothoron's spitter, leaving Shocker and career minor-leaguer Dixie Davis as the team's only effective starters.

For the 1921 season, Burke was replaced by Lee Fohl, known far and wide as the manager who was once fired by the Indians for allowing a Cleveland hurler to pitch to Babe Ruth with the game on the line. Like Burke, however, Fohl was a smart baseball man. He installed 21-year-old Marty McManus at second base after veteran Joe Gedeon was suspended for his alleged role in the Black Sox scandal, and solved the team's third base problem with another youngster, Frank Ellerbe, whom he picked up in a deal with the Senators. He also showed faith in righthander Elam Vangilder, who had made a name for himself in the Western League but had failed to catch on in a couple of stints with the Browns.

St. Louis finished third with 81 wins, serving notice on the AL that the Yankees were not the only up-and-coming club. George had another great year, batting .371 and leading the league in steals. Once again, he reached double digits in doubles, triples, homers and stolen bases—although this time seven other major leaguers joined the club, including Hornsby, who dominated the NL batting stats for the third-place Cardinals. At one point in the season, George collected 10 consecutive hits.

The 1922 campaign began on an embarrassing note for George. In the final tune-up for the regular season, the Browns faced the Cardinals in what was dubbed the “City Series.” In the final game, he challenged the arm of leftfielder Austin McHenry and was thrown out at home three times. McHenry was a budding superstar whose career was cut short that year by a brain tumor.

George's fortunes improved considerably after the real games started, and the Browns looked ready to make their move. When Judge Landis suspended Ruth and teammate Bob Meusel for illegally barnstorming the previous winter, it looked like St. Louis had its chance. George led a balanced attack that kept pace with New York throughout the spring, but the Browns could not nudge the Yankees out of first. When Ruth and Meusel returned, St. Louis gave no ground, and in early July it was the Browns atop the standings.

George was having another spectacular season, both at bat and on the basepaths. So too were McManus, Williams and Jacobson—all of whom were on pace to knock in 100 runs. While George stayed in front of Cobb in the batting race, Williams opened a home run lead on Ruth that the Bambino never was able to close. Williams also swiped 37 bases, making him history's first 30-30 man.

The season turned during an August series in St. Louis, when the Yankees trounced the Browns and retook the league lead. New York managed to maintain its paper-thin lead throughout the summer, finishing one win better than the Browns, who would go down in history as one of the great runners-up of all-time. George finished with a .420 average, which still stands as the AL record. During one stretch, George hit safely in 41 straight games to establish a new mark. It would stand until Joe DiMaggio's amazing 1941 season. George also led the league with 51 steals, 134 runs, 246 hits and 18 triples.

Yet as the Yankees overshadowed the Browns, Hornsby once again outdid George. The Cardinal superstar won the Triple Crown with 42 homers, 152 RBIs and a .401 average. He outslugged George by 128 points and topped him in runs, hits and doubles. Hornsby was not the defensive player George was, but in this new world of robust slugging, only the older fans, who still pined for scientific baseball, bothered to notice. George took some consolation in being named the AL's Most Valuable Player, although Cobb could have laid claim to this honor. But as a player-manager, the Georgia Peach was ineligible under baseball's rules.

The 1923 season found the Browns back in the second division, and without their star first baseman. A sinus infection got the better of George during the off-season, and it progressed to the point where it affected his optic nerves and he was seeing double. He missed the entire year, with Dutch Schliebner taking his place. The Browns still had a formidable offense, but without George rifling line drives and swiping bases, it didn't scare anyone. Fohl was shown the door after 101 games, and Jimmy Austin, now a coach, filled in until the end of the year.

That winter, the Browns asked George to be the club's player-manager and he accepted. The team was unsure whether their star would return to form, but wanted him in the dugout regardless. Although his tremendous vision never fully returned, his talent for hitting a baseball was undiminished. He batted .305 in 1924 and managed the Browns to a fourth-place finish, then guided the team to 82 victories and third place in 1925. George, now 32, posted a .345 average and reached double digits again in doubles, triples, homers and steals. He also threatened his own record when he hit in 34 consecutive games.

George's fine run as player-manager of the overmatched Browns came to an end after the 1926 season. He had his worst year at the plate, batting just .289, and the club lost 92 games. After Jacobson was dealt to the Red Sox at mid-season, Williams, Gerber and McManus were the only other regulars left from the 1922 team. Shocker was a Yankee, and Vangilder was on the downside of his career. Football star Ernie Nevers made seven starts, but he proved better at running the ball than pitching it.

George opened 1927 at first base for the Browns, with Dan Howley at the helm. Howley had piloted Toronto to the International League crown the previous season—no small feat in an era when the Baltimore Orioles ruled the IL roost. St. Louis showed little improvement in his first year, but George rebounded with a .327 average, 97 RBIs and a league-leading 27 stolen bases. Not bad for a 34-year-old back then, but there were too many men on the roster in their 30s for the Browns, including WIlliams (37), Gerber (35), center fielder Bing Miller (35) and catcher Wally Schang (37). Meanwhile, not a single pitcher on the staff had an ERA under 4.00.

Over the winter, the Browns made a series of deals to address this situation. They packaged George with Vangilder and two other players and sent them to Detroit for Heine Manush and Lu Blue. The Tigers then sold George to the Senators, who dealt him to the Boston Braves 20 games into the 1928 campaign.

Under normal circumstances, George would have been the toast of the team, which was on pace for a 100-loss season. But as luck would have it, the Braves had earlier acquired none other than Rogers Hornsby. So although George tattooed NL hurlers to the tune of a .340 average, his teammate hit .378 to win the batting title. For a team to have two of the greatest hitters in the game and notch just 50 wins gave some inkling as to the quality of the rest of the roster.

The Browns, meanwhile, finished third behind New York and Philadelphia. The trades the team had made paid off handsomely. Manush had 241 hits and batted .378, and Blue put in a solid season as George's replacement. General Crowder, picked up in a 1927 trade, combined with Sam Gray—acquired from the A's for Bing Miller—to win 41 games.

In 1929, Hornsby found himself on the pennant-contending Cubs vying for a Triple Crown at age 33. George, now 36, was still stuck in Boston. He led the team with 205 hits, 40 doubles, 79 RBIs and a .326 average, but the wheels were gone, and so was much of his enthusiasm. He stuck around for the 1930 season and hit .309 in 116 games, but he wasn't even the team's best first baseman. That honor went to switch-hitter Johnny Neun, who batted .325 in limited action.

Unable to find regular work in the majors, George signed with Rochester of the International League. He played 159 games—at age 38 the most in his career—and hit .303 with 45 extra-base hits. Still nimble around the sack, he led the IL in assists. It marked the eighth time in his career he finished a season at the top of this category.

During the 1931 offseason, George and his wife Kathleen became parents for the fourth time. David Sisler, born that October, would go on to become a basketball star for Princeton University, and later pitched seven seasons of major-league ball. George's second son, Dick, was a first baseman and outfielder for eight major-league seasons. His 10th-inning homer in the final game of the 1950 season gave the Philadelphia Phillies the NL pennant. Dick was the batting coach for the pennant-winning Reds in 1961 and again in 1962, when Dave joined the pitching staff. George's oldest son, George, Jr., never made it to the majors, but served for many years as president of the International League. The Sislers also had a daughter, Frances, who was in attendance when Ichiro Suzuki broke her father's hit record in 2004.

With four growing children to feed, and the country in the depths of the Depression, George had to seek further employment in baseball. Released by Rochester prior to the 1932 season, he accepted an offer to be player-manager of the Shreveport-Tyler club in the Texas League. In 70 games at first base he batted just .287, but did steal 17 bases. The following year he returned to St. Louis and worked for a printing company. Later in the decade he opened a sporting goods business. George operated ball parks for night softball games, served as president of the American Softball Association, and ran a national semipro baseball tournament.

In 1939, George was inducted into the Hall of Fame with Eddie Collins, Willie Keeler and Lou Gehrig. Also enshrined were old-timers Cap Anson, Charles Comiskey, Candy Cummings, Buck Ewing, Charlie Radbourne and Al Spalding. The ceremony, which also included enshrinees from 1936 to 1938, was held at the opening of the museum, and represented the greatest assemblage of baseball talent in history.

Fans got to see George in uniform again a few years later when old friend Branch Rickey hired him as an instructor for the Dodgers in 1943. When Rickey—whom George always called “Coach” or “Mr. Rickey”—moved over to the Pirates, he took George with him. He continued to serve as an organizational batting instructor into the 1970s.

In 1961, George was featured in a Sports Illustrated article entitled “The Thinking Hitter.” He had already minted one batting champion in Dick Groat and was in the process of creating another one out of his star pupil, Roberto Clemente, with whom he had worked steadily since the early 1950s.

George later retired to St. Louis, where he died two days after his 80th birthday, in 1973.

George Sisler had the ability to wait an extra split second before committing himself—at the plate, on the bases and in the field. This skill enabled him to use his mind a little longer than the competition, and the result was a staggering record in each of these statistical departments. His .340 lifetime average places him in the Top 15 of all-time, his 164 triples in the Top 40, his 2,812 hits in the Top 50. Had he not sat out the 1923 season, George could have undoubtedly reached the 3,000-hit plateau. He led the league in steals four times—unheard of for a first baseman—and had the best range at his position for a dozen years.

In his playing days, Sisler's fans assumed he would succeed Ty Cobb as baseball's most complete player. But times changed, criteria changed, and although his skills were still valuable, the little things he contributed to his team no longer held the same value they did when he first learned the game. A stolen base meant a lot in 1915, as did a sensational play at first base. In 1925 those things weren't what the fans remembered when they left the ballpark. George must have felt the same kind of frustration as Cobb when the fans roared for the raw-boned sluggers who increasingly manned their positions.

There were times when Cobb picked out a lighter bat and drilled balls into the grandstand just to prove he could, and the way George handled a 42-ounce bat, one wonders if he could have done the same with a 36er. Could George have become a 40-homer man? Would he have been satisfied to work out more walks at the risk of more strikeouts? Could he have driven in 120 runs a year with a retooled game?

Whether he could have or not, he didn't, and baseball experts who fail to look beyond a player's batting average don't see the secondary stats to warrant his inclusion among the game's elite players. Still, until Ichiro laid claim to his all-time hit record, it was regarded by most fans as one of those marks that would likely last forever. And not many players have been able to put that on their resumes.

The bottom line on George Sisler is that he was the best at what he did when he did it, and Ichiro notwithstanding, it is unlikely baseball fans will ever see a player with his unique combination of skills again.