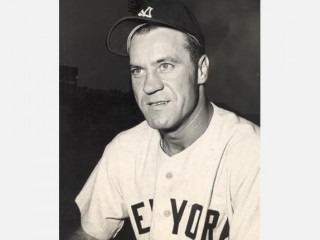

Hank Bauer biography

Date of birth : 1922-07-31

Date of death : 2007-02-09

Birthplace : St. Louis, Illinois

Nationality : American

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2010-10-16

Credited as : Baseball player MLB, New York Giants,

0 votes so far

In his youth, Hank played ball as often as he could. He was an aggressive hitter and baserunner, and as he neared his final, barrel-chested stature of six feet and 200 pounds, he could also be fairly intimidating on the mound. His nose—flattened and somewhat off-center after being broken in a basketball game—gave him an extra-tough look.

Hank was the kind of kid who refused to back away from any challenge. He didn't doubt he had what it took to be a big leaguer. After playing American Legion ball and starring for Central Catholic High School, Hank got his big break, thanks to his brother, Herman, who was a minor leaguer in the Chicago White Sox system and arranged for a tryout for his younger sibling. The Sox liked what they saw and signed Hank to a contract. He began his pro career in 1941, joining Oshkosh of the Class-D Wisconsin State League. He pulled triple duty in the outfield, infield and on the mound. In all, Hank appeared in 108 games and batting .262 with good power.

Though baseball was Hank’s love, he also knew that it was no way to make a steady living. Prior to signing with Chicago, in fact, he had already begun to work as a union pipe-fitter, which provided dependable employment in the land of beer breweries. His first job was repairing furnaces at a bottling plant.

Hank put baseball and pipe-fitting on hold after Pearl Harbor, and joined the Marines in January of 1942. He spent the next three years in the military, fighting in the Pacific theater during World War II. He volunteered for duty as a Raider, a forerunner of the Special Forces.

Hank was made a platoon Sergeant and saw heavy action in several island assaults, suffering shrapnel wounds in his back and thigh and also contracting malaria. On Okinawa, Hank commanded a 64-man platoon, of which 58 were killed. His wounds at that battle were his ticket home. Upon his return, Hank proudly displayed two Purple Hearts, two Bronze Stars and a chestful of campaign ribbons from places like Guadalcanal, Emirau and New Georgia. Years later, locker room neighbor Joe Page was still picking tiny bits of shrapnel out of Hank’s back.

Happy to be home in one piece, Hank was prepared to pick up where he left off, as a pipe fitter. Danny Menendez, a scout working for the Yankees remembered seeing Hank as a teenager and asked his brother Joe—who was tending bar—what ever happened to his little brother. Hank tapped Menendez on the shoulder and said, “That’s me.” The scout signed him as a free agent.

Hank was ballplayer in the mold of his childhood heroes, the St. Louis Cardinals. The fabled Gas House Gang—led by Frankie Frisch, Pepper Martin, Ripper Collins and the Dean brothers, Dizzy and Paul—won the World Series in 1934. Like many kids his age, Hank lived and breathed with his beloved Cards, the good and the bad. By junior high, he was already smoking cigarettes, a habit the he continued as his baseball career resumed.

Hank spent the 1946 season with Quincy of the Three-I League. Playing the outfield exclusively, he hit .323 with 90 RBIs in 108 games. This convinced the Yankees to promote him to their top farm team in Kansas City, where he once again hit .300 and showed consistent power. A quality defensive player with a strong arm, Hank was credited with 13 assists against only four errors for the Blues in 1947.

Hank continued to evolve as a player in 1948, turning in another excellent season for Kansas City. A dangerous pull hitter, he reached double-digits in doubles, triples and homers, and knocked in an even 100 runs. At age 26, Hank was entering his prime. The Yankees called him up during their three-way stretch-run battle with the Boston Red Sox and Cleveland Indians, but his contributions were meager. After playing his first game for manager Bucky Harris on September 6—in which he rapped three singles in his first three at-bats—Hank made 18 more appearances and ended up at a buck-eighty with with a homer and nine RBIs.

Over the winter, there was much discussion about the Yankees’ future. They were getting a little long in the tooth, while the Red Sox seemed on the verge of a dynasty. Even the most ardent New York fans dared not dream of a pennant, especially after clownish Casey Stengel of the Oakland Oaks was tabbed as the surprise choice to replace Harris as the club's skipper.

Hank arrived at spring training in 1949 with an outfield job his for the taking. First baseman George McQuinn had called it quits, and 39-year-old Tommy Henrich was moved to the infield to take his place. Joe DiMaggio, nursing a heel injury, would be unavailable until at least June. Left fielders Johnny Lindell and Charlie Keller, meanwhile, were on the downside of their careers.

Stengel mixed and matched his lineup, finding at-bats for his righthanded flychasers (including Hank) when opponents threw lefties at the Yankees, and loading his lineup with lefties like Henrich, Bobby Brown, Cliff Mapes and Gene Woodling when righties were on the mound. Woodling, who had previously seen major-league time with the Indians and Pittsburgh Pirates, was coming off a huge season with the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League.

Stengel’s platooning worked. The Yankees tore out of the gate and survived assorted injuries to open a slim lead on Boston. DiMaggio returned to the team before the All-Star break and hit .346 the rest of the way. Hank logged 95 games in the outfield, primarily in right, but also manned center for 25 games while DiMaggio was hurt. He hit .272 with a solid .432 slugging average. Henrich and Mapes played right when Hank was on the bench.

Over the years, Stengel never completely gave up the idea of platooning Hank. He did come to recognize, however, that the team was missing something when Hank was not in right field. This was a tricky position to play in Yankee Stadium, and Hank seemed well-suited to it. He took smart lines to fly balls and was accurate with his relays when hits rolled into the gap. Hank also became something of a master at leaning over the short wall in dead right and pull back home runs. In 1955, he made one of the greatest fielding plays in stadium history. Harvey Kuenn laced a pitch to the wall in right-center. Hank was not close enough to make a backhand stab, so he reached out with his bare right hand and deflected the ball into the glove of a stunned Mickey Mantle for a spectacular out.

Hank saw action in three of the five World Series games in 1949 against the Brooklyn Dodgers. He got one hit as the Yankees won the championship with relative ease. His ensuing check was a well-timed bonus. A few weeks later, Hank married Charlene Friede, who had worked in Kansas City as the club’s secretary. They continued to live there, buying a house in the suburb of Prairie Village and raising four children—Hank Jr., Herman, Bebe and Kelly.

The newlywed blossomed as a hitter in 1950, batting .320 with 13 homers and 70 RBIs in 113 games. He split time in right with Mapes and also spelled Woodling in left. Hank had earned the respect of enemy baserunners by this time, plus the appreciation of the home fans. They cheered when he sprinted to first after walks, and when he took out middle infielders on double plays. Johnny Pesky once commented that “the whole earth trembled” when Hank was bearing down on the pivot man.

Hank could also be heard in the dugout—a high-pitched scream that didn’t seem to fit his battle-hardened face, which was famously compared to a clenched fist.

The Yankees, now sold on Stengel’s magic, stocked their lineup with more talented role players, including 37-year-old slugger Johnny Mize and veteran bullpen arms Tom Ferrick and Joe Ostrowski. A late-season waiver deal for Johnny Hopp—who was second in the NL with a .340 average—gave them even greater depth.

A couple of youngsters, Billy Martin and Whitey Ford, also worked out nicely for Stengel in 1950. Martin would become the manager’s favorite player, while Ford pitched well enough to help the Yankees maintain a comfortable lead over the Detroit Tigers, Red Sox and Indians.

Ford had overslept prior to his first start for New York, but got the W after an uncomfortably late clubhouse arrival. Hank cornered him after the game, telling the rookie that if he had lost, he’d be dead. Ford won nine of ten decisions that year, and the Yankees defeated the Philadelphia Phillies in the World Series in four very close games. Hank started all four but managed only two hits.

Hank turned in another good year in 1951. He batted .296 in 116 games, with nearly a third of his 103 hits going for extra bases. He also began to forge a lifelong friendship with rookie Gil McDougald.

When the '51 season opened, it looked as if Hank might be grabbing some significant pine. Teenage switch-hitting phenom Mickey Mantle had a God-like spring and laid claim to the rightfield job. But an inevitable slump earned Mantle a trip back to Kansas City—though he returned to finish with 13 homers in 341 at-bats. Mantle got about half the starts in right, while Hank split his time between right and left, stepping in for Woodling against lefties.

Hank and Mickey would eventually become famous running buddies. The Mick often joked that Hank taught him how to dress, how to talk…and how to drink.

Mantle was in right against the New York Giants when the World Series began that October. In Game 2, he caught his spikes in a drain as he and DiMaggio converged on a short fly. Mantle was carried from the field. Hank, who appeared in all six games of the Yankees’ 4–2 victory, filled in for him in right and was the star of Game 6. He drilled a bases-loaded triple to give the Yanks a 4–3 lead, and then made a nice sliding catch on a dying quail by Sal Yvars to end the World Series with the tying run heading for home.

Hank opened the 1952 season with a different number on his back. He had worn 25 since his rookie year, but switched to 9, which he would wear for the remainder of his Yankee career. At 29 going on 30—and with three rings—he was a bona fide pinstripe veteran at this point. While Hank did not like being platooned, by this point he had come to recognize the wisdom in Stengel’s strategy.

Confident in his clubhouse status, Hank was becoming a more vocal leader. He was one of the most fundamentally sound players in the league, rarely made mistakes and was tough on teammates who did. Hank and Charlene had come to depend on those fat World Series checks, so if he caught a teammate screwing up or holding back, he would scream, “Don’t mess with my money!”

The respect accorded Hank by the players and fans was reflected by the fact that he was named the starting rightfielder in the 1952 All-Star Game. He batted second for the AL and went 1-for-3. He legged out a fifth-inning single against Bob Rush of the Chicago Cubs but was thrown out stealing by Roy Campanella.

With DiMaggio retired and Mantle in center, Hank was New York's full-time right fielder, appearing at the position in 122 games. He also played 18 games in left field. With regular time, his numbers soared. A line drive hitter who pulled everything, he drilled 31 doubles, six triples and 17 home runs. His 162 hits were a career high, while his .293 average was the third-best mark on the team behind Mantle and Woodling.

The Yankees needed every one of those hits. After playing .500 ball for the first two months, they found themselves in a dogfight with the Indians the rest of the year. Heading into September, they faced a brutal schedule that had all but three of their final 21 games on the road. They edged the Tribe by just two games.

The Yankees and Dodgers hooked up for the championship for the third time in Hank’s career. Down three games to two, New York won the final two games in Ebbets Field, but Hank was no help. He had just one hit in the series, despite playing in all seven games.

Hank’s contributions to the Yankees were too profound to be overshadowed by his fall failures—especially when New York kept winning—but his sub-.200 World Series performances were starting to get a little old. It is safe to say that no one in the Bronx, including Hank, suspected that he would one day embark on history’s most celebrated postseason hitting streak.

The 1953 season was another excellent one for Hank. He batted .304 in 133 games, sitting against tough righties with Irv Noren (owner of his former #25) taking his place. Hank started in right again during the All-Star Game and went 0-for-2 with a walk off Curt Simmons of the Phillies. That fall, the Yankees beat the Dodgers again in the World Series, in six games. Appearing in every contest, Hank got six hits and scored six runs.

It had become something of a pre-World Series clubhouse custom at this point for Hank to remind his fellow Yankees that they were playing with “his” championship share. In 1954, however, Hank failed to cash a Series paycheck for the first time since his rookie year. The Indians finally put it all together, and the Yankees, despite winning 103 times, finished second. Hank hit .294 and started the All-Star Game for the third and final time. He played 104 games in right, with Noren and Enos Slaughter seeing time there, too.

Hank saw a bump in playing time in 1955, and responded with 20 home runs and 97 runs scored, and hit .278 as the Yankees returned to the top of the AL heap. It was not an easy season, as age and injuries decimated the pitching staff and also took its toll on the lineup at times. New York hung tough and edged the Indians by three games.

The World Series was a letdown for the Yankees, Facing the Dodgers, they fell in seven games to their traditional whipping boys. Lost in the sauce was Hank’s .429 average, tops among all hitters.

The Yankees returned the favor in 1956, beating Brooklyn in seven. Hank had nine hits in seven games, including his first postseason home run. It capped a nice power surge for him. During the regular campaign, he established a new career high with 26 dingers. His increased homer production came at a price, however, as his average dipped to .241. Like most Yankees, Hank spent the year watching Mantle in slack-jawed awe as he won the Triple Crown, then blasted three World Series home runs and saved Don Larsen’s perfect game against the Dodgers. Hank, meanwhile, began a consecutive-games hitting streak that would stretch into the 1958 World Series, where it finally ended at 17 in a row.

Hank had another solid season in 1957. He hit .259 with 18 home runs, and at the age of 35, he led the AL in triples with nine. But Hank’s most famous hit that season was a punch that he may or may not have thrown at a Bronx deli owner during a brawl at the Copacabana. The scene was Martin’s 29th birthday, and Hank was one of six Yankees (Mantle, Ford, Berra, and Johnny Kucks were the others) at the club's 2:00 a.m. show featuring Sammy Davis Jr. Behind the Yankees and their wives was a group of boisterous bowlers celebrating a league championship.

When Davis asked them to quiet down, one of the crew fired back a racial slur. Hank stood up and defended Davis, leading to a tussle near the men’s room. Accounts vary wildly, but Hank claimed that the Copa bouncers stepped in and “took care of things.” The man who was slugged, Edwin Jones, claimed that Hank knocked him unconscious. Hank, it should be noted, had no love for racists. Having seen men blown to bits fighting for freedom, he was quick to defend those oppressed others because of their skin color. Once, when friend and teammate Elston Howard was being taunted by a racist fan, Hank climbed onto the dugout roof and had to be restrained from going into the stands. Still, he denies throwing the infamous Copa punch.

When the Copa story broke in the papers the next day crediting Hank with the KO, he showed his knuckles to teammate Moose Skowron, who had been babysitting his daughter that evening. According to Skowron, they were unmarked. Hank was later sued by Jones, but his good name was cleared by Berra, who stated with absolute certainty that “nobody never hit nobody.” Hank was facing a possible Grand Jury hearing on the matter, but the case never went to trial. The foreman emerged from the courtroom with DA Frank Hogan and told Hank that he was free to go—“we threw the SOB out of court.” The foreman then asked for an autograph.

The incident led to Martin’s banishment from New York, but things calmed down and the Yankees cruised to the pennant by eight games over the Go-Go White Sox, who had made things interesting with a fast start. But New York took 14 of their 22 meetings, which created a comfortable gap in the standings.

The Yankees faced the Braves in a see-saw World Series that eventually tilted Milwaukee’s way. Hank batted leadoff for the Yankees and collected eight hits in seven games, including two more home runs.

Hank logged his 10th year as New York’s primary rightfielder in 1958, with Berra spelling him against selected righthanders. Hank, who batted .268 with 12 homers and 50 RBIs, was beginning to show his age. The Yankees finished 10 games in front of the pack and prepared for a rematch with the Braves.

The series did not start well for New York. They dropped three of the first four games, and watched in dismay as their top winner, Bob Turley, was massacred in Game 2. Hank had made a couple of uncharacteristic bonehead plays in the opener, but redeemed himself by supplying all of the offense in Game 3, knocking in all four runs in a 4–0 victory. Warren Spahn, the opening game winner, blanked the Yankees in Game 4. Hank was held hitless for the first time after reaching base safely in 17 straight World Series games.

Turley returned to pitch a 7–0 shutout in Game 5 at Yankee Stadium to keep the series alive. Back in Milwaukee, the Yanks won 4-3 in 10 innings—with Turley getting the save—to force a seventh game. New York took the series with a 6–2 victory before a packed house at County Stadium. It was the first time since 1925 that a team had rebounded down one game to three to win the World Series.

Hank hit four home runs against the Braves to put him into some fast company, tying a record shared by Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig and Duke Snider. It was later broken by Reggie Jackson in 1977.

Hank saw action in 104 games as New York’s right fielder in 1959. It was a down season for the Yankees—who finally had that off-year the experts had been predicting for a decade—and a disappointing season for Hank, who managed a mediocre .238 average with just nine home runs.

Hank's dipping numbers led in part to a trade that ended his playing career in New York. On December 11, 1959, Hank was included in a multi-player deal between the Yankees and the club that fans not-so-jokingly called their “JV,” the Kansas City Athletics. He was packaged with Larsen, Norm Siebern and Marv Throneberry for Roger Maris and a couple of other players. Maris took Hank’s spot in right and the number off his back. The Yankees handled their announcement of the trade poorly. Hank found out from the papers that he would no longer be wearing pinstripes.

Hank returned with mixed feelings to the city where he had long made his off-season home. Managed by Bob Elliott, the 1960 Athletics had some decent hitters, but their pitching and defense was atrocious. In spring training, the players vying for outfield spots included Siebern, Bob Cerv, Russ Snyder, Whitey Herzog, Dick Williams and Bill Tuttle.

Hank caddied for the 26-year-old rightfielder Snyder most of the year, batting .275 with three homers and 31 RBIs. The Athletics lost 96 games and finished in the cellar. Maris won the MVP in New York, which rebounded from ’59 to win the pennant.

After the season, the Athletics were purchased by Charlie Finley. He changed the official name to A’s and declared that the New York shuttle was closed for business. He then traded Kansas City’s best pitcher, Bud Daley, to the Yankees.

Hank’s final year as a major leaguer came in 1961. Joe Gordon started the season as Kansas City’s skipper, and Hank ended the year at the helm. Finley and GM Frank Lane summoned Hank to a meeting at which he was asked if he would like to manage one of the organization’s minor-league teams. Hank said he would be interested in managing, but was not interested in returning to the bush leagues. “Well then,” Finley said, “you’re the manager of the Kansas City ball club.”

The A’s went 35–67 under Hank in 1961 and finished tied with the Washington Senators for the worst record in the league, with 100 losses. Prior to being released as a player in late July, he was technically a player-manager. The AL would not see another one until Frank Robinson in 1974.

Prior to his release in 1962, Hank batted .264 with three homers in 43 games. His final career totals were .277 with 164 home runs, 703 RBIs, plus seven World Series rings in nine postseason appearances. Though hardly underappreciated, Hank was viewed by his peers as being somewhat underrated. In a poll taken during the 1980s that included opinions of more than 1,000 former players, Hank was tied for 20th as history’s most underrated player. Enos Slaughter, Billy Williams and Roger Maris were ranked 1-2-3.

The A’s skipper for all of the '62 campaign, Hank guided a team thin on talent once again, though Siebern put up nice numbers despite a total lack of protection. For sportswriters at the postgame debriefings, one of the few highlights was watching Hank drain a beer and then crush the can flat with his fist. Was Hank picturing Finley's head when he squashed those cans? It's not out of the question. The owner was constantly meddling with managing decisions, and Hank simply gritted his teeth and did as he was told. That got old pretty fast, however.

Somehow, the A’s improved by 10 victories. Their 72 wins was the second-best total since the club moved west from Philadelphia. Hank quit two days before the end of the season rather than waiting for Finley to fire him. “When a man loses his pride,” he said, “he loses everything.”

Hank quickly accepted an offer to join the Baltimore Orioles coaching staff. He came to a team in some disarray. The previous season, new manager Billy Hitchcock had lost control of the young Orioles. Pitcher Milt Pappas questioned his managerial skills in the press and slugger Jim Gentile openly flaunted training rules. Hank watched in dismay as the turmoil continued in 1963. The club had enough young stars to finish fourth, but in Hank's mind that talent was going to waste.

In 1964, Hank gladly accepted the manager’s job. He instituted a number of get-tough team policies including a curfew and a rule against drinking at the hotel bar. No one dared defy him. As one player put it, on his best days, Hank looked like an “M-1 ready to go off.” Hank held one clubhouse meeting during which he laid down the basic rules. He concluded by reminding the Orioles, “If you ream me, I got the last ream.”

The '64 pennant race was a wild one—the best since Hank’s rookie season in the Bronx. The Yankee dynasty, on the verge of crumbling, did not seem up for another stretch run. That left the White Sox and Orioles to battle things out. As the season headed into September, Hank had the Orioles poised to take the flag. Order had been restored and young studs Brooks Robinson and Boog Powell were powering an offense that featured on-base specialists Luis Aparicio and Siebern, who had been plucked off the A’s roster in a swap for Gentile. The loud-mouthed All-Star had punched his own ticket when he ran into Hank during the off-season and greeted him with a congenial, “Hello, Hitler!”

Time Magazine all but handed the Orioles the pennant when it featured Hank on the cover of its September 11 issue. Baltimore promptly imploded, limping along at .500 as the pinstripers pulled together under their beleaguered manager Berra and roared to victory. Ironically, Yogi was canned after the World Series, and Hank was honored as AL Manager of the Year.

In 1965, Hank moved Powell to first base and entrusted the centerfield job to 21-year-old Paul Blair. The Orioles finished third again, but they were headed in the right direction. Hank planned to promote young defensive standouts Dave Johnson and Andy Etchebarren into the regular lineup, and felt that his pitching was deep enough to survive the ups and downs of 162 games. During his many years in New York with Stengel, Hank had learned a thing or two about assembling a resilient staff. He also knew that pitching and defense were worthless without an intimidating bat in the lineup.

Prior to the 1966 campaign, the Orioles put that final piece in place when they acquired Frank Robinson from the Cincinnati Reds for Milt Pappas. Sportswriters joked that Hank was now just the second-meanest guy in the American League. Pappas’ spot in the rotation was filled very ably by 20-year-old Jim Palmer, who ended up leading the staff with 15 victories.

It was Robinson, however, who made Hank look particularly good. He destroyed pitching in the new league, finishing atop the charts with 49 homers, 122 RBIs, a .316 average and a .637 slugging percentage. The Orioles won the pennant by nine games and headed into a World Series showdown with the glamorous Los Angeles Dodgers.

The Orioles were given two chances to unseat the defending champions—slim and none (aka Koufax and Drysdale). But Hank was confident that his pitching could shut down the LA hitters. This, in fact, was how the series played out. Dave McNally struggled early in Game 1 after being staked to a 3–0 lead, so Hank called journeyman Moe Drabowsky in from the bullpen before things got out of hand. Drabowsky proceeded to fan 11 Dodgers, while closing out a 5–2 victory with 6 2/3 innings of remarkable relief.

Palmer, Wally Bunker, and McNally threw shutouts in the next three games to give the Orioles an unexpected sweep. For the second time in three seasons, Hank was named AL Manager of the Year.

Hank was now an object of fascination to the world outside baseball. Time, Look, Life, Newsweek and other national publications featured stories that cast him as sort of a living anachronism. As the length of men’s hair began to creep over their ears, his Marine crew cut became America‘s most famous. He was even hired to do a hairspray commercial—the idea being that he would be the last guy who would use a product so unmanly.

When Hank decided to kick smoking, it was a signal to other war veterans that it was time to turn the corner on this nasty habit. Hank was the drill sergeant with a heart of gold—and a brain for baseball.

Not everyone agreed. Robinson, who had become quite vocal in the areas of players rights and human rights, was hardly shy about advertising the fact that he was no fan of the manager’s. When the Orioles sank to sixth place in 1967, Robinson may well have hastened Hank’s firing.

Hank resurfaced on the managerial scene in 1969, wearing the green and gold of the A’s, who were now in Oakland. His first go-round with Charlie Finley had been unpleasant, but this time he had the talent to do something special. The A’s had a galaxy of young stars, including Catfish Hunter, Blue Moon Odom, Rollie Fingers, Joe Rudi, Bert Campaneris, Sal Bando, Rick Monday and Reggie Jackson. Bauer was so impressed with Jackson that he convinced his old teammate, Joe DiMaggio, to join the club as a special coach.

The A’s, in their second season in Oakland, finished second in the new AL West, with 88 victories. Hank wasn’t around for the last 13 games. The unpredictable Finley fired him and put John McNamara in charge. It would be Hank’s last major-league managing job. His career record was 594–544, with one championship.

Hank’s next baseball job came as a minor-league manager for the New York Mets. He led the Tidewater Tides in 1971 and 1972, working with the likes of John Milner, Jon Matlack and Buzz Capra. Hank hoped to return to the majors in 1973, but nothing materialized. He decided that life in the minors was too much, and he retired from baseball to run a liquor store he had purchased.

Hank returned to the game briefly in the early 1980s to work as a scout for the Yankees, evaluating clubs as they went through Kansas City. But he held no illusions about managing again. Hank felt that the players had lost their respect for authority and wanted no part of baseball’s new world.

Fans in New York never forgot Hank and his Yankee teammates of the 1950s—their love for those championship clubs never waned. To the contrary, in fact, it seemed to grow with each passing year during the 1980s and 1990s. When Mantle began doing the baseball card show circuit, he invited Hank and his buddies to tag along and make a few bucks signing autographs alongside him. During these shows Hank reconnected with Skowron, and they became the closest of friends. Hank also appeared at a handful of Yankee fantasy camps, before launching his own fantasy camp business in partnership with Skowron.

The Moose was at Hank’s bedside in February of 2007 when he entered the hospital, sick with cancer. On February 9, Hank Bauer lost his long battle with the disease. He passed away in Shawnee Mission, Kansas at the age of 84.