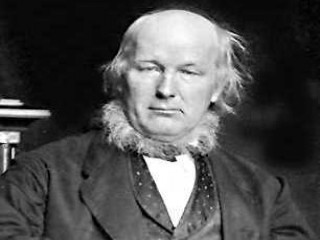

Horace Greeley biography

Date of birth : 1811-02-03

Date of death : 1872-11-29

Birthplace : Amherst, North carolina, United States

Nationality : American

Category : Politics

Last modified : 2011-06-27

Credited as : Newspaper editor, and politician, New York Tribune

Horace Greeley was born on Feb. 3, 1811, in Amherst, N.H. At the age of 14 he became an apprentice on a newspaper in Vermont, where he learned the journalist's and printer's arts. He followed his trade in New York and Pennsylvania before moving to New York City in 1831. He worked on miscellaneous publications before founding a weekly literary and news magazine, the New Yorker, in 1834. Though not a lucrative undertaking, this established Greeley as one of the able young editors of popular journalism.

Greeley's political emergence as both a Whig and equalitarian caused him to seek out practical political solutions, while also encouraging debate and radical experimentation. In 1838 he edited a partisan publication, the Jeffersonian, for the New York Whigs. He also began an association with Whig leaders William H. Seward and Thurlow Weed that continued for 20 years.

In the election of 1840 Greeley edited the memorable Log Cabin for the Whigs. Meanwhile he was working on an organ of social and political news and discussion for the general reader: in 1841 he launched the New York Tribune.

The key to Greeley's editorial policy was his belief that progress demanded a serious effort to better society. He abhorred revolution or turbulence among the masses. Though one of his major interests was free land for settlers in the West and he approved of individual initiative, he also welcomed cooperative efforts and social planning. The Tribune published the theories of Albert Brisbane, who wanted society organized into cooperative communities. To the Tribune as literary editor came George Ripley, a founder of the radical commune Brook Farm. Charles A. Dana, who became Greeley's second-in-command, wrote articles in praise of French Socialist Pierre Proudhon, who believed that "property is theft." Greeley later published the foreign comment of Karl Marx.

Greeley's radicalism was qualified by his more general orthodoxy. He held rigid temperance principles and scorned woman suffragists and divorce reformers. He adhered to conventional political patterns. Moreover, his receptivity to social experiment enabled him for many years to avoid the slavery problem as being remote from immediate issues. As his paper's most influential commentator, Greeley produced a flow of articles and editorials, and the Tribune rapidly gained national importance.

Greeley was often caricatured as absentminded, half bald, carelessly dressed, and with childish features fringed by whiskers. He was impetuous and impressionable, committing himself rashly to numerous, disparate ventures and fads. These included the Red Bank (N.J.) Phalanx, spiritualism, vegetarianism, phrenology, and a formidable list of investments and loans, of which almost none were profitable. Generous and improvident, he dissipated the fortune the Tribune's success had brought him.

Greeley's lecturing began as an adjunct of his political and social interests, but this took increasing portions of his time. He traveled throughout the East and in 1859 to San Francisco. He also lectured in Europe. Though his speaking engagements became lucrative, they did no more for his financial state than had his journalism. Hints toward Reforms (1853) includes some of his lectures.

Greeley's commitments interfered with his home life. He had married Mary Youngs Cheney in 1836. In youth his wife had been talented and enthusiastically reforminded, but she deteriorated into a hypochondriac. Though Greeley's Westchester County farm was known for its modern agricultural techniques, the house itself was randomly administered. The unhappy household was further upset by the fact that of their nine children only two survived to adulthood.

Equally unfortunate was Greeley's political career. He wanted to influence state and national politics and gain power for himself, but he was no match for adroit associates who used the Tribune's columns. Greeley's ambitions for Henry Clay were frustrated. He had to accept Zachary Taylor's Whig candidacy in 1848, though Taylor was a slave-holder and a hero of the Mexican War, which Greeley did not endorse. Greeley's own dreams of office brought him no more than a 90-day election to Congress in 1848.

Nevertheless, Greeley's editorial voice grew with the increasing strength of the Free Soil party and abolitionism. He opposed the Compromise of 1850, with its notorious Fugitive Slave Law provision. In 1856 he became one of the founders of the Republican party and spoke out clearly against the extension of slavery.

Greeley's editorial policies during the Civil War swung erratically from appeals for peaceful separation to the all but fatal slogan "On to Richmond!" His most famous editorial, "The Prayer of Twenty Millions," in 1862, symbolized Northern determination to make the war sacrifices meaningful by abolishing slavery. In 1864 Greeley, with President Abraham Lincoln's sanction, probed peace possibilities in a meeting with Confederate agents. His efforts, though futile, helped make clear that Southern plans did not include preservation of the Union.

In the postwar era Greeley cooperated with the Radical Republicans, opposing President Andrew Johnson and appealing for African American rights. A meeting of disillusioned party members in 1872 sought alternatives to the era's corruption and political incompetence. As a result, the Republican Liberal party was formed, and Greeley became its presidential candidate.

His qualities of reason and compassion expressed themselves during Greeley's campaign. But the Radical Republican attack was fierce and effective, and he was overwhelmingly rejected at the polls. The strain of the election and his sense of personal humiliation, together with his wife's death a week before the election, unbalanced Greeley's mind. He died in a private mental hospital on Nov. 29, 1872.