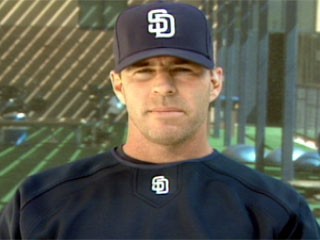

Jim Edmonds biography

Date of birth : 1970-06-27

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Fullerton, California

Nationality : American

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2010-10-25

Credited as : Baseball player MLB, outfield with the San Diego Padres,

0 votes so far

Jim was a natural athlete from a very early age. Fast and strong, he possessed good hand-eye coordination and absorbed information quickly. But it wasn't always easy to tell whether Jim really cared all that much about winning and losing. He was known to be laid-back, even by Southern California standards.

What truly set Jim apart in baseball was his keen eyesight. (Years later, when the Angels tested him, it was discovered that he had 20-15 vision.) He could pick up a ball in flight—whether batted or thrown—a half-tick before other players. As he moved on to higher levels of play, that ability enabled him to rise above his peers.

Jim had another skill that he used to great advantage in the other sports he played—he was ambidextrous. As a kid, Jim determined he would throw and bat exclusively left-handed, so his right-handed ability did not have much of an impact in baseball. Still, he liked taking grounders as a righty during infield practice.

Jim's talent with either hand did make him an exceptional basketball player. It also helped a great deal in soccer and football.

Baseball quickly developed into one of Jim's passions. He was in the right place to hone his game. Diamond Bar had a long tradition for Little League excellence. Lance Parrish was the first player to bring national recognition to the town, in the 1960s. Kevin Gross followed his lead in the 1970s. Jim added to the legacy in the 1980s. In his last tournament for Diamond Bar, he batted .529 with three home runs and nine RBIs.

Jim was a big fan of the California Angels, who played 15 miles away in Anaheim Stadium. When the team signed free agent Rod Carew in 1977, Jim became transfixed with the sweet-swinging lefty's scientific approach to hitting. The youngster went nuts when the Angels won their division in 1979, and he was crestfallen when they crashed and burned against the Baltimore Orioles in the ALCS.

When Jim entered Diamond Bar High School in the fall of 1984, he was he was one of his town's top performers. His beloved Angels were on the rise, too. In the 1986 playoffs, California found itself one strike away from defeating the Boston Red Sox and advancing to the franchise's first World Series. But the team's legendary collapse over final three games ended all hopes of a championship. Jim took the loss as hard as anyone.

Two years later, he stood on the same field as the Angels, playing in the Southern California sectional championship game. With a .548 batting average, the high school senior was drawing serious attention from scouts. They also liked his pitching arm. In one game, Jim fanned 19 of the 21 batters he faced.

There was only one knock against Jim. He didn't seem to get upset or excited about anything. When he struck out, he often smiled at the pitcher. When he made an error, he never appeared fazed. Baseball people took that as a sign that he lacked the go-for-the-throat attitude needed to claw your way to the majors—and stay there. It was a tag that would haunt Jim for more than a decade.

Still, who could ignore his picture-perfect swing, blazing speed and flair for making impossible catches and on-the-money throws? Not the Angels. Jim's hometown team grabbed him with their seventh pick in the 1988 draft—behind Jim Abbott and Gary DiSarcina and ahead of Damion Easley.

Early in his minor-league career, Jim was spectacular at times, but just as often, hegot hurt or was simply a disappointment. In his first year of pro ball, with the Bend Bucks in the Class-A Northwest League, he batted only .221 with no home runs. In 1989, Jim spent considerable time on the disabled list for the Quad City Angels of the Midwest League, also a Class-A team. In 31 games, he hit .261.

It was another two years of Class-A ball for Jim in 1990 and 1991. Playing for the Palm Spring Angels in the California League, he showed flashes of brilliance, though most of his high points were overshadowed by injuries. After missing nearly all of the '91 campaign, he had less than 200 games and only six home runs on his four-year resume. Meanwhile, other prospects were shooting past him in the Angel system, including fellow outfielders Tim Salmon and Garrett Anderson.

ON THE RISE

Jim's first blip on the organization's radar screen came in 1992, in the Class-AA Texas League. He started the year with the Midland Rockhounds, and by mid-season, he was feeling as comfortable as he ever had. Finally injury-free, Jim launched five dingers in a six-game span in July, including a three-homer game against the Wichita Wranglers. For the first time, the idea that big-league stardom awaited him seemed like a reality.

The California brass rewarded Jim with a promotion to the Edmonton Trappers. Against Triple-A pitching in the Pacific Coast League, he continued to swing a hot bat. Jim ended the season at .307 with 14 homers and 68 RBIs.

Intrigued by Jim's sudden jump in production, the Angels included him on their 40-man roster in spring training of 1993. Though he batted .429 in eight exhibition contests, he was eventually optioned to the Triple-A Vancouver Canadians, California's new PCL affiliate. As would become his M-O, Jim began the season on fire. In April, against the Calgary Cannons, he went 6-for-6. Later in the summer he posted a pair of five-hit contests. For the year, in 95 games, Jim hit .315 with 28 doubles, four triples, nine home runs and 74 RBIs.

The Angels recalled Jim in September, and he made his major-legue debut in left field at Detroit against the Tigers. He opened to mixed reviews. Though Jim whiffed in his first at-bat, against veteran righty Bill Gullickson, he also threw out Tony Phillips at home on the first defensive chance of his career. The following day, in SkyDome against the Toronto Blue Jays, Jim doubled off Duane Ward for his first big-league hit. Despite batting just .246 for the Angels, he rasied eyebrows in the organization with his glove work, which included several diving catches.

The 1994 season saw Jim win a full-time role with California. A platoon left fielder coming out of spring training, he outplayed Bo Jackson and sent him to the bench. He also stalled J.T. Snow’s ascension to the starting lineup, occasionally handling duties at first. Jim wasn't the only youngster on the roster. The edict put to GM Whitey Herzog was to cut payroll, which he followed to a tee. After lefty aces Mark Langston and Chuck Finley and veteran slugger Chili Davis, manager Buck Rodgers had a roster full of inexperienced players. It was hardly a shocker when the Angels finished the strike-shortened campaign at a woeful 47-68. Rodgers, tabbed as the fall guy, lost his job in May and was replaced by Marcel Lachemann.

When he was healthy, Jim acquitted himself well in his rookie campaign. Used as a utility man of sorts, he played four different positions but committed just three errors. In 289 at-bats, he hit .273 with 13 doubles, five homers and 37 RBIs. His numbers might have been better were it not for a fluke in injury in New York, when a throw from Mike Gallego of the Yankees nailed him in the back of the neck. Jim suffered a mild concussion and experienced numbness in his legs. He was back in action a few days later, but didn't achieve a full recovery until weeks later.

Jim's quick return earned him the grudging respect of veteran teammates—not to mention reporters and fans—many of whom eyed the rookie with a measured amount of suspicion. Jim's laid-back attitude raised questions about whether he had the grit to succeed in the big leagues. He turned off many observers early in the season when he nonchalantly said he expected to do well in the majors. Jim seemed self-centered and lacking in team spirit. More than once, as he prepared in private for a game, he was told to get on the field and stretch with his teammates.

At one point, sensing a growing clubhouse problem, Davis and batting coach Rod Carew pulled Jim aside to explain the ways of the world in the majors. Having Carew take an interest in him was quite a thrill. But it was Davis's role as big brother that made the biggest impression. Although Jim still rubbed some guys the wrong way, he toned down his act enough to get by—and convince the Angels they could trade away center fielder Chad Curtis and hand him the job.

Jim started the 1995 season on a tear. Instead of inside-outing the ball, he began looking for pitches he could drive when the count was in his favor. By July, he was among the league leaders in RBIs. For the first time in his career, Jim was named to the All-Star team. The secret to his increased power was a tip from Carew. The former batting champ admired Jim's even swing and suggested that he concentrate more on lifting the ball. The results were astounding. In the season's first half, Jim posted a 23-game hitting streak (second-best in franchise history to Carew's 25), and enjoyed a scorching two-week stretch that included seven homers and 23 RBIs.

The Angels were riding high as well, opening a sizable lead in the AL West. Salmon, Snow and Anderson were all having exceptional seasons, while Langston and Finley continued to anchor the rotation. In the bullpen, newcomer Lee Smith was pitching like someone half his age. Unfortunately, the team came back to earth in August and September. The problems began when shortstop Gary DiSarcina injured his wrist. Then Jim hurt his back, and the Angels really tumbled. In one of the more embarrassing collapses in baseball history, California blew an 11-game bulge and was forced to win its final five games just to tie the Seattle Mariners. The once-promising season ended in a one-game playoff, a 9-1 loss at the Kingdome.

Jim's final stats reflected his stark development as a hitter. He set career-highs in batting (.290), home runs (33) and RBIs (107), and established a franchise record 120 runs scored. His defense was also sensational, with eight assists and just one error in 139 games. So good was Jim that voters named him to The Sporting News All-Star team over Ken Griffey, Jr.

From the heights of 1995 came a shocking decline for Jim. With an outfield billed as one of baseball's best and a new club owner in the Walt Disney Company, fans expected big things from the Angels in 1996. Lachemann was proving to be a calming influence in the dugout, and the rotation of Langston, Finley, Brian Anderson and Jim Abbott was a lefthanded hitter's nightmare. But California never put it together. The team struggled to score runs and prevent them, ranking 13th in the AL in the both departments. When the Angels limped home at 70-91, Lachemann got the axe.

Jim was part of the problem. While he terrorized righties (.350 and 25 HRs), he couldn't touch southpaws. Injuries to his abdomen, groin, left shoulder and thumb also limited his production, costing him more than a month on the bench. As a result, his power numbers, RBIs and batting average all plummeted. As his frustration grew, Jim popped off to reporters, railing about the difficulty of playing everyday in the majors. His ill-timed rant didn't help matters. The papers portrayed Jim as a whiner, an opinion shared by some in the California front office who believed the Angels would be better off without him.

One of those who seemed to agree with that assessment was Terry Collins, the new manager of the Angels (now of Anaheim) for the 1997 season. Fiery to a fault, he demanded the same level of intensity from his players.

Though the team's roster changed only slightly from the year before, Collins saw no reason why the Angels couldn't compete for the division title. He pushed and bullied his club all year long, getting strong performances from the likes of Darin Erstad, Dave Hollins, and Salmon—guys who repsonded to his rah-rah approach. With young guns Jason Dickson and Troy Percival emerging as reliable big-league arms, Anaheim surged to a record of 84-78, just six games out of first place.

Jim, however, didn't appreciate Collins's style. He also butted heads with first base coach Larry Bowa. Though Jim batted .291 with 26 homers and 80 RBIs—and captured his first Gold Glove—Collins and Bowa wondered whether he always gave his best effort. Both were from baseball's old school and bristled when they felt their center fielder "cut the pie" on what should have been routine plays. In June, Jim made the catch of the year in Kansas City, robbing David Howard with a miraculous over-the-head, diving grab on the warning track. But his reaction to such plays was often viewed as self-aggrandizing. Jim, who battled torn cartilage in both knees throughout the year, was also accused of milking his injuries. Whenever he tried to defend himself, he did more damage than good.

Jim quieted some of his critics in 1998. Avoiding the DL, he became a fixture in the heart of the Anaheim order, batting over .300 for the first time as a major leaguer (.307), posting 68 extra-base hits and leading the team in runs scored. He also claimed his second Gold Glove. Most important, Jim picked up his play down the stretch, as the Angels chased the Texas Rangers in the final month for the top spot in the AL West.

Though Anaheim fell short by three games, it was quite a turnaround from the previous season. Other key offensive performers were Mo Vaughn (signed as a free agent from Boston), Erstad, Salmon and Anderson. The pitching staff, meanwhile, got unexpected boosts from knuckle-baller Steve Sparks and Japanese import Shigetoshi Hasegawa. In relief, Percival saved 42 games and fanned 87 hitters in 66 innings.

All the goodwill Jim built up in the '98 campaign disintegrated the following year. He hurt his groin early in the season, and then aggravated a shoulder injury lifting weights while on the DL. Forced to undergo surgery, Jim didn't return to the lineup until August. His teammates weren't happy. They felt a lack of commitment to fitness over the winter was the true source of his health problems. Erstad, who took over in center field, was the most outspoken of the Angels.

California struggled without Jim, dropping far off the pace in the division. With Salmon also on the DL and Vaughn nursing a sprained ankle, the offense struggled—even with rookie Troy Glaus plugged into the lineup. The pitching wasn't much better. Journeyman Mark Petkovsek was the club's best hurler with 10 wins, and Percival talked about wanting out of town.

By the time Jim returned in August, the Angels were more than 20 games behind the Oakland A's. He never found his stroke and finished with the worst numbers of his career (.250, five homers and 23 RBIs). That winter, with the trade rumors flying, Jim realized that he might have worn out his welcome in Southern California. He told the team he wanted to stay, but with Erstad ready to replace him, the writing was on the wall. Jim was mentioned in potential deals with the Mariners, A’s and Yankees. The negotiations with New York were the most serious—until the Angels insisted on minor leaguer Alfonso Soriano.

Enter the Cardinals, looking for a slugger to complement Mark McGwire in an already potent lineup. St. Louis GM Bob Gebhard thought Jim was a good fit and pressed Anaheim's Bill Stoneham to make a deal. The two ultimately settled on a swap in March. The Angels got 18-game winner Kent Bottenfield and young infielder Adam Kennedy, while Jim headed for St. Louis.

MAKING HIS MARK

The Cardinals believed they had stolen the game's top center fielder—and quickly signed Jim to a contract extension. In his first at-bat after the deal was announced, he received a standing ovation from St. Louis fans. Jim struck up a friendship with McGwire, a fellow southern California boy, and the Cardinal clubhouse became one of the happiest in the big leagues.

Those good vibrations translated onto the field. Even without Bottenfield, St. Louis had plenty of pitching depth. Darryl Kile and Pat Hentgen were signed as free agents, and southpaw Rick Ankiel had a once-in-a-lifetime arm. The batting order featured speed and power. With a lineup that included J.D. Drew, Eric Davis, Ray Lankford, Edgar Renteria, McGwire and Jim, manager Tony La Russa could mix and match his hitters any way he wanted.

Rejuvenated by his new surroundings, Jim got off to a torrid start. After five weeks, he led the NL in virtually every significant offensive category. He stayed hot through the All-Star break, with his average way over .300 . No one was questioning his work ethic anymore or told him he looked like he was hot-dogging. La Russa—as well as the St. Louis faithful—couldn't understand how Jim had ever had a reputation problem.

Jim's biggest cheerleader was McGwire. The big redhead missed half the year with a bad knee, but remained in close contact with the team. With Big Mac out of the lineup, Jim developed into a team leader, keeping the Cardinals ahead of the Cincinnati Reds in the NL Central. Observers noted a new approach at the plate, as he worked deeper into counts waiting for balls he could hammer. His strikeouts increased, but so did his power numbers and on-base percentage. Jim ended with 42 homers and 108 RBIs, and drew 103 walks. He also earned another Gold Glove.

More meaningful to Jim than the personal accolades was the Cardinals' division title. St. Louis played terrific ball from July on and outdistanced Cincinnati by 10 games. Jim was a major contributor, as was mid-season acquisition Will Clark, who filled in admirably for McGwire.

In the Division Series, the Cards shocked many with a sweep of the powerhouse Atlanta Braves. Jim was dominant at the plate, collecting eight hits and seven RBIs in three games against the league's best staff. But St. Louis ran out of gas against the New York Mets in the NLCS. Jim failed to come through in key at-bats, and no one picked up the slack. With the series all but decided in the ninth of Game 5, he took a seat on the bench to give McGwire some swings.

Jim followed his marvelous 2000 season with another terrific campaign in 2001. He stayed healthy for the second year in a row, batted over .300 again, and won his fourth Gold Glove. Though McGwire lost a second season to injuries, Jim received help from Albert Pujols, an unheralded rookie who had started the previous season in Class-A Peoria. Together, they formed a lefty-righty punch that accounted for 67 homers and 240 RBIs.

The Cardinals also got outstanding years from Fernando Vina, Drew, and the unlikely third base platoon of Placido Polanco and Craig Paquette. Matt Morris and Kile headlined a pitching staff bolstered further with a late-season trade for Woody Williams. St. Louis needed all it could get from this group, because the power-laden Houston Astros and the Sammy Sosa-led Chicago Cubs also had excellent teams. After falling below .500 after the All-Star break, the Cardinals rallied and began gaining ground.

The division race went down to the wire. The Cards took 12 of 13 in early September to challenge the frontrunning Astros. St. Louis went on to tie Houston for first, while the Cubbies finished just a handful of games behind. Jim sizzled down the stretch, hitting close to .350 and driving in a run a game over the campaign's last eight weeks. Though Houston and St. Louis posted identical records of 93-69, the Astros were awarded first place by virtue of their head-to-head record with the Cardinals, who snagged the Wild Card.

St. Louis met the Arizona Diamondbacks in the Division Series, and the teams split the first four contests. Jim tried to get in a grove, but the dynamic duo of Curt Schilling and Randy Jonhson kept him quiet. In the deciding fifth game, Morris and Schilling squared off in a classic, which Arizona won 2-1. (he Diamondback rode that momentum all the way to a thrilling World Series title over the Yankees. Jim finished the series topping all players with 11 total bases and a pair of home runs.

The 2002 season found the Cardinals minus McGwire, who called it a career after two injury-plagued seasons. Pujols made up for this loss with another superb year at the plate, Renteria enjoyed his finest campaign to date and Scott Rolen, acquired in a July trade, added another big bat to the lineup.

Jim was in the middle of most of the team's offensive fireworks. He recorded career highs in batting average (.311) and on-base percentage (.420), collected 61 extra-base hits and scored 96 runs. His performance with runners on base dropped, however, as his RBI total sagged to 83. In all fairness, his production was hurt somewhat by limited opportunities.

St. Louis's season took a heartbreaking turn in June when longtime announcer Jack Buck and staff stalwart Kile died within a four-day span. Jim and Kile were particularly good friends, and the pitcher's untimely death created a huge void. Jim's rock-solid leadership during that time earned him newfound respect around the majors. On the DL with a sprained wrist earlier in the month, he came back before it was healed to play through the pain. His toughness didn't go unnoticed in the clubhouse.

With Jim serving as a unifying force, the Cardinals somehow held it together and began to build a lead in the NL Central. Maintaining a small cushion over the Astros throughout the summer, they turned on the jets in September, going 21-6 to run away with the division.

The Cardinals dethroned the Diamondbacks in the Division Series with a three-game sweep, and then faced the Giants for the NL pennant. San Francisco stunned St. Louis by taking the first two games at Busch Stadium. The Cards bounced back to win Game 3 at Pac Bell. The next two contests were nailbiters, and the Giants came out on top in both.

The prospects for a pennant seemed less than good for St. Louis in 2003. The long-suffering Cubs boasted a formidable pitching staff, and the Astros had their usual solid mix of live arms and bats. With closer Jason Isringhausen starting the campaign on the mend from elbow surgery, the Cards hovered around .500 early in the year. Morris and Williams remained the staff aces, while Pujols continued to grow as a hitter.

Jim, as usual, was on fire in the season's opening months. He was on pace to bat better than .300 with more than 40 homers and 100 RBIs when injuries shut him down. His emerging leadership skills helped the Cardinals stay in the thick of things until September. Unfortunately, they lost two key series and dropped out of first place for good.

Jim played through injuries to his calf, ribs and hip, but it was a sore right shoulder that ultimately brought him down. He missed 25 games and played hurt in at least 100 more. Still, he finished with respectable numbers—39 homers, 89 RBIs and a .275 average. Add those to the big-time stats Pujols and Renteria put up, and it might have been enough to keep the Cards on top. But with neither Morris nor Isringhausen healthy the entire year, the pitching staff never found its rhythm and the club lost a dozen games it might otherwise have won. For the first time since Jim arrive in St. Louis, the team finished out of the playoffs.

Optimism was guarded headed into the 2004 season. The Cardinal lineup looked good with the trio of Pujols, Rolen and Jim, but the pitching staff—with unproven starters Jason Marquis and Chris Carpenter joining the rotation—didn't seem to have the studs to compete with the Cubs and Astros.

Jim and the Cards started slowly. His batting average through May was well under .300, and St. Louis was only treading water in the NL Central. But Jim was one of several hitters who got hot in June, and the Cardinals moved from a few gamesgames behind the Reds to first place.

St. Louis took complete control of the division in July, building a huge lead over the slumping Astros and Cubs. Jim was sensational. For the month, he batted .381, adding 13 homers and 27 RBIs. With the NL Central just about sewed up, the Cards positioned themselves for the playoffs. Their biggest move was the acquisition of lefty slugger Larry Walker, who helped balance the righty-dominated lineup.

The Cardinals finished the season at 105-57, for the top record in all of baseball. Jim, meanwhile, posted some of the best numbers of his career, including a .301 batting average, 42 homers, 38 doubles, 102 runs, 101 walks and and 111 RBIs. The combination of him with Pujols, Rolen and Walker was a modern-day Murderers Row.

St. Louis drew the Los Angeles Dodgers in the first round of the playoffs and won the first two games easily. Jim homered and drove in two runs in Game 1. After the Cards sutmbled in Game 3, they rebounded to end the series in Los Angeles.

Next St. Louis squared off in the NLCS against the streaking Astros, who had disposed of the Braves in five tight games. Jim paced a 10-7 victory in Game 1, knocking in three runs. Rolen was the hero the following day, as the Cardinals moved ahead 2-0 in the series. With the action shifted to Houston, the Astros seized the advantage with three wins in a row. Pitching was the key, as Jim and his teammates were limited to a total of seven runs.

Game 6, back in St. Louis, was a close contest full of classic postseason drama. The Cardinals enjoyed a one-run lead going into the ninth, but Isringhausen coughed it up, and the game went into extra innings. In the twelfth, Jim stepped to the plate with Pujols on first. Dan Miceli tried to beat him with a high fastball. Jim jumped all over it, launching a soaring drive into the right field bullpen to force a Game 7.

The Cards faced Roger Clemens in the decider, and the Rocket shut them down through the first five innings. He began to tire in the sixth. After an RBI-double by Pujols, Clemens chose to pitch to Rolen with Jim waiting on deck. The powerful third baseman lined a home run to left, and the St. Louis bullpen closed the door over the last three stanzas. The Cardinals advanced to the World Series for the first time since 1987, setting up a rematch of the '67 series with the Red Sox.

Unfortunately for St. Louis fans, their club got steamrolled in four games. The series opened with a wild slugfest at Fenway Park, but the Cards fell 11-9. Jim's only contribution offensively was a bunt single. His most important at-bat came in the eighth against Keith Foulke with two outs and the bases loaded. Jim struck out swinging. The next day, with a hobbled Curt Schilling on the mound for Boston, the Red Sox won again, 6-2.

As the series moved back to St. Louis, Jim and the Cardinals needed a boost. They had their chances early against Pedro Martinez, but couldn't buy a clutch hit. Boston held on for a 4-1 victory, and the demoralized Cards were done. Derek Lowe threw seven shutout innings two nights later, as the Red Sox celebrated their first World Series title since 1918. Jim was one of several players to don the goat horns, going just 1-15 with six strikeouts in four games.

For Jim, the conclusion to 2004 was a bitter disappointment. The 2005 campaign was no fun, either. Nagging injuries limited his effectiveness at the plate. Although he produced numbers most centerfielders would kill for, they were not up to his standards. Even so, Jim's 29 homers and 89 RBIs helped St. Louis win 100 games—best in the NL. Jim was still great in the field, winning his sixth straight Gold Glove.

Much of the credit for the team's success belonged to Chris Carpenter, who came into his own with a 21-win season. Pujols also had a big year, belting 41 homers and scoring a league-leading 129 runs. The Cards looked like a good bet to return to the World Series. After sweeping the San Diego Padres in the NLDS, however, they fell to Roy Oswalt and the Astros in an exciting seven-game NLCS. Jim hit well against San Diego but was a noon-factor against Houston.

The injuries continued to pile up in 2006 for St. Louis, not just for Jim but for the entire team. Rarely during the year were all eight regulars in the lineup. Jim played just 110 games and missed much of the second half because of a concussion suffered trying to rob Joe Crede of a home run in late June. He also logged most of the year on a painful left foot. The Cardinals still managed to hold off charges by the Astros and Reds and took the division title with a mere 83 wins.

Heading into the playoffs, the Cards were healthy for the first time all year. A fat September lead had allowed LaRussa to sit Jim, David Eckstein and other injured stars. Jim was a little rusty in an NLDS rematch with the Padres, but St. Louis prevailed in four games. Next up came the Mets, who were without sore-shouldered Pedro Martinez. In a thrilling series, the Cardinals won the pennant in seven games. Jim hit a pair of home runs against New York pitching.

The unlikely NL champion Cardinals met the unlikely AL champion Tigers in the World Series. After splitting the first two games, St. Louis seized control of the series in Game 3 thanks to Jim. His clutch two-run double gave the Cards the lead in a 5–0 victory. They polished off Detroit three days later.

Jim was exultant in victory. It was his first World Series ring. After a painful and unproductive regular season, Jim felt great knowinghe had been a bona fide contributor. In 16 games in the playoffs and World Series, Jim knocked in 10 runs.

The Cardinals were spent by 2007. Injuries decimated the club again, and St. Louis ended the year with a losing record. Jim was hurt again, and his numbers showed it. He hit .252 with just 29 extra-base hits.

Is Jim washed up? The Padres don't think so. They believe he can rebound, and he has assured them he will be in peak form by the start of Spring Training. Jim has graduated from spoiled young star to respected elder statesman. When he talks now, teammates normally listen.

JIM THE PLAYER

A generation from now, Jim will likely be remembered as one of the most spectacular center fielders of his era. There will be no talk of "cruising" when his highlight reel rolls.

Ever since he put Rod Carew’s advice to work, Jim has steadily grown into the role of a slugger. If he is past the injuries that sapped his strength in 2006 and 2007, the big stick should return—though his home run totals in pitcher-friendly Petco Park may not show it.

Over the years, Jim’s hands and wrists have become stronger, enabling him to drive pitches to left that he once dinked for singles. Jim is considered a "guess hitter," but that reputation sells him short. He has developed a book on pitchers that includes a very sophisticated take on their tendencies. When he gets the pitch he’s expecting, he’s all over it.

Of course, when Jim guesses wrong, he can look pretty bad. But Jim can be pretty entertaining in failure. He actually has fun listening to the crowd ooh and aah when he swings and misses.

Years ago, that type of attitude drew the ire of those in the California organization. Jim's approach was so spacey that he once said he didn't like hitting in the leadoff spot at home, because the jog in from the outfield after the visiting team hit in the top of the first tired him out. But Jim has matured, and teammates have learned that he's a gamer—even if he rarely waves the pom-poms.