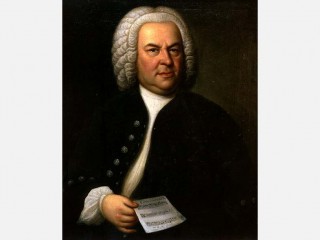

Johann Sebastian Bach biography

Date of birth : 1685-03-31

Date of death : 1750-07-28

Birthplace : Eisenach, Germany

Nationality : German

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2010-05-24

Credited as : Composer of the Baroque, Brandenburg concertos, Toccata and Fugue

Revered for their intellectual depth, technical command and artistic beauty, Bach's works include the Brandenburg concertos, the Goldberg Variations, the Partitas, The Well-Tempered Clavier, the Mass in B Minor, the St Matthew Passion, the St John Passion, the Magnificat, The Musical Offering, The Art of Fugue, the English and French Suites, the Sonatas and Partitas for solo violin, the Cello Suites, more than 200 surviving cantatas, and a similar number of organ works, including the celebrated Toccata and Fugue in D minor and Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor.

Regarded posthumously as one of the greatest composers and surprisingly organ builders of all time, Bach was a part of a long lineage of musical geniuses who was rooted in the Baroque era. His most famous works include the Brandenburg Concertos, Mass in B Minor, and various other pieces of music that have been collected over time. Bach’s innovation and genius was often inhibited by the politics of the day and his constant search to find financial backing for his musical endeavors.

As the youngest son to Johann Bach and Elisabeth Ambrosius, he learned to play music from his father and attended Georgenkirche, where his skills were further developed and honed. Bach was always interested in organ music and would have learned a great deal from Johann Christoph Bach who worked at the school as an organist. Upon the death of his parents, the young Bach was taken care of by his oldest brother, who was also an organist. At some point in his childhood, Bach also took keyboard lessons from Johann Pachelbel. During his time at school, he studied church music and was influenced by several renowned organists of the day, namely Reinken and Georg Böhm.

While spending time in Thuringian, he was made familiar to choir music of the day and the practice of the Lutherans. Here, he also learned much about rigid style, logic, and discipline. Additionally, somewhere along the line, he learned more about the French organ and other stringed musical instruments. Following his time there, he moved to Leipzig, where the wrote several cantatas in rapid succession.

Looking for work and financial support, he began writing cantatas for an official at Saxony and his family. In fact, it is thought that his first inspiration for the classic Mass in B Minor was written for the elector. And, upon meeting a Russian envoy who was inspired by Bach’s ability, he commissioned the young composer to write the Goldberg Variations. In the latter years of his life, it wasn’t certain what sort of disorder Bach had to endure. Due to his illnesses, he wasn’t able to finish his Art of Fugue, which was still published after his death. Modern musical composers still look to Bach for inspiration and wonder how such a musical genius was not regarded more highly in his day.

Legacy and modern reputation

After his death, Bach's reputation as a composer declined; his work was regarded as old-fashioned in favour of the emerging classical style. Initially he was remembered more as a player, teacher and as the father of his children, most notably Johann Christian and Carl Philipp Emanuel. (Two other children, Wilhelm Friedmann and Johann Christoph Friedrich, were also composers.)

During this time, his most widely known works were those for keyboard. Mozart, Beethoven, and Chopin were among his most prominent admirers. On a visit to the Thomasschule, for example, Mozart heard a performance of one of the motets (BWV 225) and exclaimed "Now, here is something one can learn from!"; on being given the motets' parts, "Mozart sat down, the parts all around him, held in both hands, on his knees, on the nearest chairs. Forgetting everything else, he did not stand up again until he had looked through all the music of Sebastian Bach". Beethoven was a devotee, learning the Well-Tempered Clavier as a child and later calling Bach the "Urvater der Harmonie" ("Original father of harmony") and, in a pun on the literal meaning of Bach's name, "nicht Bach, sondern Meer" ("not a brook, but a sea"). Before performing a concert, Chopin used to lock himself away and play Bach's music. Several notable composers, including Mozart, Beethoven, Robert Schumann, and Felix Mendelssohn began writing in a more contrapuntal style after being introduced to Bach's music.

The revival of the composer's reputation among the wider public was prompted in part by Johann Nikolaus Forkel's 1802 biography, which was read by Beethoven. Goethe became acquainted with Bach's works relatively late in life through a series of performances of keyboard and choral works at Bad Berka in 1814 and 1815; in a letter of 1827 he compared the experience of listening to Bach's music to "eternal harmony in dialogue with itself". But it was Felix Mendelssohn who did the most to revive Bach's reputation with his 1829 Berlin performance of the St Matthew Passion. Hegel, who attended the performance, later called Bach a "grand, truly Protestant, robust and, so to speak, erudite genius which we have only recently learned again to appreciate at its full value". Mendelssohn's promotion of Bach, and the growth of the composer's stature, continued in subsequent years. The Bach Gesellschaft (Bach Society) was founded in 1850 to promote the works; by 1899, the Society had published a comprehensive edition of the composer's works, with a conservative approach to editorial intervention.

Thereafter, Bach's reputation has remained consistently high. During the 20th century, the process of recognising the musical as well as the pedagogic value of some of the works has continued, perhaps most notably in the promotion of the Cello Suites by Pablo Casals. Another development has been the growth of the "authentic" or period performance movement, which, as far as possible, attempts to present the music as the composer intended it. Examples include the playing of keyboard works on the harpsichord rather than a modern grand piano and the use of small choirs or single voices instead of the larger forces favoured by 19th- and early 20th-century performers.

Bach's contributions to music—or, to borrow a term popularised by his student Lorenz Christoph Mizler, his "musical science"—are frequently bracketed with those by William Shakespeare in English literature and Isaac Newton in physics. Scientist and author Lewis Thomas once suggested how the people of Earth should communicate with the universe: "I would vote for Bach, all of Bach, streamed out into space, over and over again. We would be bragging, of course, but it is surely excusable to put the best possible face on at the beginning of such an acquaintance. We can tell the harder truths later."

Some composers have paid tribute to Bach by setting his name in musical notes (B-flat, A, C, B-natural; B-natural is notated as "H" in German musical texts, while B-flat is just "B") or using contrapuntal derivatives. Liszt, for example, wrote a prelude and fugue on this BACH motif in versions for organ and piano). Bach himself set the precedent for this musical acronym, most notably in Contrapunctus XIV from the Art of Fugue. Whereas Bach also conceived this cruciform melody (among other similar ones) as a sign of devotion to Christ and his cross, later composers have employed the BACH motif in homage to the composer himself. Some of the greatest composers since Bach have written works that explicitly pay homage to him. Examples include Beethoven's Diabelli Variations, Shostakovich's Preludes and Fugues, and Brahms's Cello Sonata in E, whose finale is based on themes from the Art of Fugue. A 20th-century work very strongly influenced by Bach is Villa-Lobos's Bachianas Brasileiras.