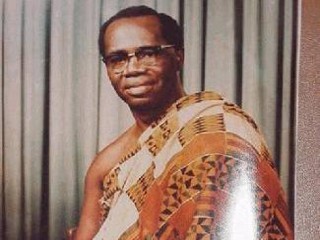

Kofi Abrefa Busia biography

Date of birth : 1913-07-11

Date of death : 1978-08-28

Birthplace : Wenchi, Gold Coast

Nationality : Ghanaian

Category : Politics

Last modified : 2011-09-07

Credited as : politician, sociologist, Prime Minister of Ghana

Kofi Abrefa Busia was a Ghanaian political leader and sociologist. A scholar by inclination and temperament, he symbolized the dilemma of the intellectual in politics—the man of thought forced by events to become the man of action.

Kofi Busia was born a member of the royal house of Wenchi, a subgroup of the Ashanti, Ghana's largest tribe. Educated at church missions and at Mfantsipim School, he became a teacher at Achimoto, Ghana's leading secondary school. After three years he attained his goal of a scholarship to Oxford, where he went in 1939. His subsequent career alternated between, and sometimes combined, scholarship, government, and politics.

In 1941 Busia returned to the Gold Coast to begin research on the Ashanti political system. In 1942 he became one of the two first African administrative officers in the colonial service. Finding the experience frustrating, he returned to Oxford, where he received a doctorate. Afterward he undertook for the colonial government a social survey of the towns of Sekondi-Takoradi. This was followed by an appointment at the University College in 1949, where in 1954 he became the first African professor.

Busia became concerned when the nationalism of Ghana's strong man, Prime Minister Kwame Nkrumah, became increasingly radical. In 1951 Busia had stood for Parliament in his home district of Wenchi in the Gold Coast's first real elections and had been defeated. Yet the chiefs still had powers. Those in Ashanti could choose six additional members of the Legislative Council, of whom Busia became one. In 1952, when the opposition attempted to regroup, it elected Busia as leader, less by choice than by elimination, and for his eminence as a scholar.

The opposition had little effect, until there arose in Ashanti a violent "National Liberation Movement" determined to rid the country of Nkrumah at any cost. Its emergence forced the holding of a new election in 1956. Busia was the movement's unlikely leader, unable to restrain or control it. This was the first real threat to Nkrumah, but his party still emerged victorious, as well as vengeful.

Ghana's independence in 1957 brought Nkrumah new power, which he used systematically to decimate the opposition. Busia regrouped the opposition into a united party and tried to develop a constructive program, but their tactics played into Nkrumah's hands. Their inability to sense the mood of the country, which at its base was still in support of Nkrumah, made of them an unconstructive opposition and of Busia a voiceless leader. By late 1958 Nkrumah was prepared to detain their leading members, and by the next year he had passed a law unseating any Council member absent for more than 20 sessions. The law was aimed directly at Busia, whose scholarly commitments took him all over the world. Threatened by immediate detention, Busia left Ghana, in circumstances that have never been explained, but probably on the advice of Krobo Edusei, a fellow Ashanti in Nkrumah's government.

The next seven years were spent in exile, with Leiden and then St. Antony's College, Oxford, as Busia's academic base. If Busia had been an unlikely opposition leader in Ghana, he was even more so in exile. But he was now too committed to the struggle against Nkrumah to settle easily into the scholarly life, although he published one book, The Challenge of Africa, and some articles during these years. The steadily increasing number of other exiles failed to rally around Busia, least of all Komla Gbedemah, Nkrumah's principal lieutenant turned exile. Nor did Western governments, before 1964, give Busia any tangible support or even encouragement. His testimony to the U.S. Congress against American aid to Ghana caused some resentment. Except perhaps in French circles, it was felt everywhere that if Nkrumah were overthrown it would not be by forces that Busia could hope to command. What was underestimated was the extent to which a revulsion had spread in Ghana against everything Nkrumah symbolized, which would rebound to Busia's benefit.

Several months after the soldiers and policemen had overthrown Nkrumah in February 1966, Busia returned to Ghana after careful negotiations with the ruling National Liberation Council (NLC). Politics were banned, and the NLC was at best divided as to how much room for maneuver Busia should be given. Its most powerful member in any event favored Komla Gbedemah, who was no doubt a more skillful politician. Busia was made chairman of a new council on higher education after he was passed over for the vice chancellorship of the University of Ghana. Tactically, Gbedemah always outmaneuvered Busia and his party was better organized, but he was tainted by his association with Nkrumah. Busia, on the other hand, was an Ashanti, and the Ashanti wanted power after so many years. Thus, with their bloc vote, Busia won the premiership in a landslide victory at the end of August 1969.

Once in office, Busia wielded strong executive powers. He instituted a stringent austerity program. The chief question that was posed by the election and Busia's years in power was whether this once reluctant politician was sufficiently in control of his own party, increasingly dominated by little-known but strong-willed younger men, and whether he was sufficiently farsighted to lead Ghana out of its economic troubles and its tribal and political bitterness. Although his commitment to a parliamentary system was nowhere in question, he authorized some actions and tolerated others that gave rise to the old doubts and some new ones as well. The defeated opposition was further enfeebled by the successful barring of Gbedemah even from membership in the new Assembly, a seat he had overwhelmingly won in his district.

Widespread discontent led to a second military coup on January 13, 1972. The presidency was abolished and the National Assembly dissolved under the regime of Lieutenant Colonel Ignatius Kutu Acheampong. Busia, who was in London receiving medical treatment at the time of the coup, was forced into exile for a second time. By the late 1970s, Ghana's economy had slid into chaos, and corruption was rife. The Supreme Military Council, which assumed power in 1975, ousted Colonel Ignatius Kutu Acheampong in 1978.

Busia spent his final years as a lecturer in sociology at Oxford University. Busia's scholarly contribution proved valuable, not only intrinsically, but also for what it has done for the African seeking his identity after centuries of colonial rule. Of the colonial period, Busia wrote that "physical enslavement is tragic enough; but the mental and spiritual bondage that makes people despise their own culture is much worse, for it makes them lose self-respect and, with it, faith in themselves." Part of the intellectual liberation in Africa has come through the systematic analysis of African institutions by Africans; Busia's major study, The Position of the Chief in the Modern Political System of the Ashanti (1951), was a ground breaker in this regard. Moreover, Busia personalized the commitment to freedom of the African intellectual, and his writings on the relevance of democratic institutions to modern Africa found a wide audience. He died in London on August 28, 1978.