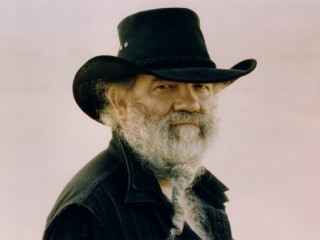

La Monte Young biography

Date of birth : 1935-10-14

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Bern, Idaho,U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Arts and Entertainment

Last modified : 2012-03-19

Credited as : Composer, Musician, the grandfather of minimal music

0 votes so far

Called "the grandfather of minimal music" by Brooke Wentz in Down Beat, La Monte Young has been a key figure in the musical avant-garde since the early 1960s. He evolved from a jazz and blues saxophonist in the 1950s to a minimalist pianist, composer, and performance artist who is still active in the 1990s. Musicians influenced by his theories include Terry Riley, a former classmate of his, and modern composers Steve Reich and Philip Glass.

Young is known for keyboard pieces stripped down to bare essentials, with extended meditations on just one chord and frequent shifts from consonance to dissonance. A prime example is his "Dorian Blues in G," in which each chord of a six-chord progression is played for a solid 20 minutes. Some of Young's pieces last for hours, and his compositions have been known to evolve over many years.

The blues has been a major influence on his work. "Young's blues are unlike any you've heard before, and at the same time they're as pure a musical illumination of the form as you're ever likely to hear," wrote Glenn Kenny in Spin. Thom Jurek claimed in the Detroit Metro Times that Young's compositions "are loosely related in concept to those of blues masters Robert Johnson, Son House and John Lee Hooker, who employed certain guitar strings as drones to lay their improvisations over."

Young's masterwork as a composer is "A Well-Tuned Piano," a piece that has developed over nearly 25 years, since the early 1960s. According to Neil Strauss in a 1994 issue of the New York Times, this composition has been called "one of the most important musical works of this quarter century." In Down Beat Wentz deemed it "a major documentation--a documentation that seems to end an era, or at least closes another chapter in modern music." Edward Rothstein opined in the New York Times, "With the creation of such works as 'The Well-Tuned Piano,' [Young] became an almost archetypal figure of the musical counterculture, devoted to varieties of Indian music while acting as a pioneer of Western Minimalism."

Born into what he called a "hillbilly" family in Pulse!, Young's first exposure to music was cowboy music. He began singing and playing guitar at about age three and learned to play the harmonica soon afterwards. His father taught him to play the saxophone when Young was seven. Blues as played by jazz musicians held a strong appeal for him early on as well. "My first experience with the blues that I can consciously recall was listening to the recording of Charlie Parker and Thelonious Monk playing 'Bloomdido,'" he told Pulse! Young listened to that recording many times as a high school student, gaining both education and inspiration from the naturalness of Parker's playing. "What's important to me about the blues," he explained, "is that even though I learned it through this very specific format of jazz, it always represented something to me that was very big and powerful that went outside of any particular style."

Young became very active on the jazz underground scene in Los Angeles in the 1950s. He frequently jammed with forward-thinking musicians like Billy Higgins, Don Cherry, Eric Dolphy, and Ornette Coleman, and became a highly accomplished alto saxophone player. Early in the decade he composed his first song, "Annod (To Donna Lee)," which he recorded with Higgins. Young later earned a spot as second chair in saxophone in the Los Angeles City College Dance Band, winning out over Dolphy.

Throughout the 1950s Young's saxophone playing evolved from jazz improvisation to more harmonically static music. By 1957 he had begun teaching himself to play the piano. Before long, he was a highly skilled pianist and was composing pieces in a minimalist style that would become a major influence on works by Philip Glass and Steve Reich.

In the late 1950s Young embraced the Fluxus movement, a group of artists and musicians who attempted to break free from conventional standards of art and music. Young was attracted to the Fluxus notion that the focus should be on the music-making process itself, and that music should be considered an evolutionary event. Young's involvement with Fluxus marked a shift away from jazz and contemporary classical composition and toward the realm of art music. He began staging Fluxus events in New York City. This Chambers Street Series featured exhibitions by leading performance artists of the day, including Yoko Ono. Many bright lights of the New York avant-garde attended these often bizarre exhibitions.

By the early 1960s Young had begun implementing "just intonation" in his musical works, a system that defied the long-standard method of tuning instruments. Just intonation is an ancient tuning system that rejects the equally tempered spacing of notes on the scale. "With the standard equal-tempered scale, the 12-note limitation makes for expedience," he told Down Beat. "There are only 'X' number of tones to deal with. But in just intonation, the fundamental frequencies of [a stringed] instrument are tuned one-to-one with the pitches that mirror the full harmonic content of the strings themselves. Since everything reinforces everything else, the nuances you get are natural rather than exaggerated. There is both simplicity and a wealth of possibilities." Employing this system allowed Young to tap into a wider span of sound options with each play of a piano key.

Around this time Young formed the Theater of Eternal Music, which became a key ensemble of the minimalist music boom. With this group he became known for his marathon piano playing and works that were continually transforming themselves, apparently with no end in sight. The group included John Cale, then a student of Young's who later became part of the pioneering rock band The Velvet Underground. With the Theater of Eternal Music, Young devoted himself to exploring the musical potential of staying on each chord change for an extended period. He became known for his trademark use of minor sevenths and slightly dissonant chords. According to Down Beat's Wentz, Young created "a masterful dialectic between the multiplicity of sounds and silence."

By 1962 Young had switched from alto saxophone to soprano, an instrument with a higher pitch. Some years later, though, he stopped playing saxophone altogether and took up singing. Throughout the 1960s and in the decades that followed, Young often performed at the Kitchen, a famed haven for avant-garde musicians in New York City. His performances there afforded him increasing visibility and helped move minimalism toward mainstream acceptance. Starting in 1970, Young began studying with noted raga singer Pandit Pran Nath. Since then he has amassed a vast collection of Indian instruments in his continuing exploration of raga.

Long fearful of recording or distributing his works due to an intense fear of being plagiarized, Young finally overcame his reluctance in 1987 and recorded a five-record version of The Well-Tuned Piano. The recording represented 23 years of work on a single harmonic theme, and it merged the ideas behind Young's 1960s jazz improvisation experiments with his sustained tone works of the late 1970s. "What appears to be repetitive and simple evolves into complex, entangled cadences," said Wentz in his Down Beat review of Piano. Wentz went on to say that Young "continually plays with the structuring of tempo, duration, and pitch, holding the listener's attention and always tricking him with surprising discordant interjections.... Every section is paced and moves succinctly from one to the next, repeating phrases until their dissonance fades to familiarity."

Many of Young's performances in the 1990s have been with the Forever Bad Blues Band, which, as of 1993, consisted of Jon Catler on guitar, Brad Catler on bass, and Jonathan Kane on drums. Describing this band in Down Beat, Young said, "It's a lot like a rock band, but we play one song for two hours." In an interview with Martin Johnson in Pulse!, he noted that working with the band helped him regain his enthusiasm for performing, which he had come to miss. Young told Johnson, "The Forever Bad Blues Band came out of the fact that in my bigger works ... I had set up the situation that was very difficult for sponsors to produce, whereas this band can go in, we can do the sound check at 3:00 and do the concert and pack up and go on to the next situation."

"The playing seemed to create an auditory space with its own dimension and depth, within which the music took place," reported New York Times contributor Edward Rothstein about a performance of Young and the Forever Bad Blues Band at the Kitchen. "As in Mr. Young's other works, the listener was always discovering something about the sound, the way it shimmered around the edges or seemed to change color." Rothstein concluded, "The music emerged as an intriguing combination of blues, 1960's happening, Eastern esthetic, rock and Minimalism."

Young has performed on a regular basis in New York City in recent years, often adding a touch of performance art to his concerts. A typical example was his appearance at Merkin Concert Hall in 1993, when he placed his musicians around the hall as if beckoning members of the audience to be a part of the performance. Many of his concerts have featured lighting designed by Marian Zazeela, his wife and collaborator, that imbues the stage with a New Age aura.

Young recorded Just Stompin': Live at the Kitchen with his band in 1993. Clearly influenced by the blues of John Lee Hooker and John Coltrane, the album also somewhat resembled the work of the Velvet Underground and modern rock experimentalists Sonic Youth. David Fricke gave the album four stars in his review in Rolling Stone. "Two hours, one song (never mind 'song,' one chord progression), no break--and zero boredom," noted Fricke. In his review of Just Stompin' in the Detroit Metro Times, Jurek said, "The band plays dynamically, from soft to hard and back, gradually building in both intensity and tension, laying back just enough--without letting the air out--to allow the musicians (and listeners) to breathe and start again, until the music reaches an unbearable pitch [that] shatters all divisions between blues, Indian classical music, punk, heavy metal, grunge, modal jazz and noise, because it's all of them and none of them at once."

Adding another chapter to his explorations of sound and space, Young created an interactive sound-and-light installation in a room above his loft in the TriBeCa section of New York City in 1994. The layout featured six speakers arranged around the room that droned continuously; magenta lighting designed by Zazeela further defined the environment. Listeners would hear a different sound mix according to how they moved in the room, thus enabling them to create new note sequences with a mere tilt of the head. "I started thinking about the possibility of doing tuned rooms in the 1960's," Young told the New York Times. "But this is one of my most advanced and far-reaching creations yet."

Young's pursuit of new musical territory in the realm of minimalism remained unabated as the 1990s wore on, and he has no regrets about his chosen path. As he said in Pulse!, "My whole life has been devoted to music because nothing else ever gave me that spiritual inspiration, that sense I was doing the right thing with my life."