Leon Hart biography

Date of birth : 1928-11-02

Date of death : 2002-09-24

Birthplace : Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2010-08-12

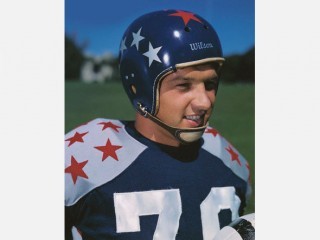

Credited as : Football player NFL, played for the Detroit Lions, won the Heisman Trophy and the Maxwell Award

1 votes so far

When Leon arrived in the NFL, he was the last two-way player to be named All-Pro on offense and defense. Very possibly, he was also the first tight end in league history.

Leon Joseph Hart was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania on November 2, 1928. He grew up in Turtle Creek, a suburb of the Steel City. From an early age, Leon had been mechanically inclined. This talent appeared to be his ticket to a productive adult life, especially during the Depression, when you fixed something until it broke for good.

Leon enrolled in Turtle Creek High School at the age of 13. Though young for his class, he was already big for his age. He opted for vocational training, but the Turtle Creek coaches took one look at him and rerouted him into college prep classes. They suspected his future lay on the gridiron. Leon quickly became the best player on the schools basketball and football teams. The football squad, in fact, did not lose a single game in his four varsity seasons.

Discovering football at Turtle Creek high was matched only by discovering Lois Newyahr. Leon's high-school sweetheart, she would later become his wife.

Leon was an intense, hard-hitting player who dug down and gave something extra on every play. He was a menace to anyone who came near him, including his own teammates. When he blocked an opponent, they stayed blocked. And, occasionally, they didnt get up. By his senior year, Leon's Turtle Creek coaches were concerned that he might kill someone by mistake. There was no way to rein Leon in, however. Not only did he tip the scales at 220 pounds, but at 6-4, he ran like someone a foot shorter.

This quality appealed to a number of major college football and basketball programs. (Leon was also a star center for four seasons at Turtle Creek High.) Moose Krause, the line coach at Notre Dame and the head coach of the school's basketball team, saw Leon as a carbon copy of himself when he was a two-sport star for the Irishonly better. It was Krause who drove through a violent storm to the train station at South Bend to pick up Leon after an alum had stranded him there early in 1946. Head Coach Frank Leahy and his staff had assumed Leon was headed elsewhere, but their interest was rekindled after Leons uncle said the boy was still very intrigued by the Fighting Irish. A recruiting visit was hastily arranged.

Krause knew his prize recruit had already visited Penn, Columbia, Tennessee, Pitt, and VMI. He was terrified that Leon would slip away. Krause arrived in pajamas and an overcoat after getting a call from Leon at the station, and later set him up in a cot in the training room. As the teenager finally dozed off, he was shaken awake by intimidating Bull Budnykiewicz, who told him to sleep somewhere else. Despite the shoddy treatment, Leon decided nonetheless that he liked Notre Dame. By the time he reported for his first practice, he stood 6-5 and weighed 245 pounds.

Leon joined a team that starred Johnny Lujack, George Connor, Emil Sitko, George Strohmeyer and Johnny Mastrangelo. The freshman began his first season as a 17-year-old third-string lineman. He watched from the bench as the Irish raced to a three-touchdown lead in its opener, and was shocked to hear Leahy call his name. On his way to the get the play from the coach, he dropped his helmet, kicked it, and then finally managed to pull it over his ears. After Leahy gave him the signal, Leon whirled and sprinted toward the huddleonly to slam into Bob Livingstone, knocking him out cold. When Livingstone came to, he observed that Hart was going to be one heck of a player once he learned how to aim his massive frame at enemy players.

The Irish halfback wasnt seeing stars. Leon played regularly and lettered as a freshmanalthough he didnt startand soon became the teams most indispensable player. By graduation, he had packed on another 20 pounds of raw muscle. At a time when 6-1 and 200 pounds was considered big, Hart seemed simply gargantuan.

No one else in the country combined his size, speed, and pass-catching ability. Indeed, for the Notre Dame offense, the threat of Leon was a greater weapon than Leon himself. He was the teams most effective blocker, in essence giving the Irish an extra offensive lineman on running plays. Leon was also fast enough to dart into the backfield and take (or fake) handoffs on end-arounds. This became a staple of the Notre Dame offense, creating utter havoc with enemy defenses. Leons explosive acceleration out of his three-point stance also made him a valuable short-yardage fullback.

On the other side of the line, Leon's quickness made him one of the top defensive ends in college football. Regardless of who was blocking him, he was able to shut down his side of the field on end runs. Opponents devised special schemes and ruses in an attempt to control Leons whereabouts, but he was no dummy. Leon called the signals in Notre Dames defensive huddle and was extremely hard to fake out of a play. He and teammate Jim Martin were the last of Notre Dames great two-way players, as Coach Leahy had instituted offensive and defensive platoons in 1949.

As a freshman, though, Leon was often on the sidelines when he wanted to be in the game. In an epic meeting between the #2 Notre Dame and #1 Army, he did not run a single play, as the two teams battled to a scoreless tie that helped the Irish finish the year undefeated and win the national championship. He did see action in the season finale, a victory over Southern Cal, reeling in a lovely pass from George Ratterman for a 22-yard score.

Leon became Notre Dames starting end on both sides of the ball as a sophomore in 1947. His blocking helped clear the way for Lujack, who masterminded the teams T-formation offense and won the Heisman Trophy for his troubles. Leon also caught a huge TD pass from Lujack in the teams 277 victory over Army. The Irish went undefeated in nine games to repeat as national champions.

Leon was named on several All-America squads after the season. Lujack and Connor also earned All-America recognition, along with linemen Bill Fischer and Ziggy Czarobski.

Leon established himself as the best all-around end in the country in 1948. As the season unfolded, some were saying he might be among the best ever at the position. Few runners could escape his clutches, and he caught 16 passes for four touchdowns to garner consensus All-America honors. With Leon leading the way, the Irish established a new school record for rushing yardage and finished unbeaten once again. It was Michigan, however, that topped the national rankings.

The game that cost Notre Dame the top spot was a 1414 tie with Southern Cal. In the contest, Leon scored a touchdown on a play that looked scripted from a bad Hollywood movie. He caught a short pass from Frank Tripucka, turned upfield and deflected no fewer than eight tackles before dragging his body into the end zone.

Not wanting to repeat the second-place finish of 48, Leon stepped up as co-captain and team leader in 1949. Leahy, meanwhile, used Leonwhom the coach was already calling one of his favorite all-time playersas an example to the rest of the team. After practice one day, he asked Leon how he felt. When Leon responded that he was tired, Leahy made him run laps, saying that he must be out of shape. The next day after practice, Leahy asked Leon the same question and he responded that he felt great. Leahy ordered him to run laps again, saying he must not have worked out hard enough.

Sure enough, Leahy asked Leon how he felt again a day later. How do you want me to feel, coach? he replied. Finally, Leahy let him off the hook and sent him to the showers. Still, the coach rode his star all season longmostly because he knew Leon could take it. Any small mistake he made was instantly pointed out to his Irish teammates, often with a derisive, Look at Mister All-American!

Leon would later comment that the work ethic Leahy instilled in him at South Bend served him well during his days in the NFL, not to mention as an owner of several successful businesses when his football days were over. Leon appreciated that his coach had never made an issue of the fact that he often missed large chunks of practice because of his engineering classes. He was willing to be Leahys occasional whipping boy in return.

Leahy would not have dared to treat his other co-captain, Jim Martin, in this way. While Leon was the teams big, brash, rah-rah leader, Martins authority was earned during World War II. He had been a reconnaissance swimmer, which is a fancy way of saying that he swam through enemy minefields at night to chart the best course for landing craft before island invasions.

Despite the leadership of Leon and Martin, the Irish were not expected to win the national title in 49. Their quarterback, Bob Williams, was unproven, and the team seemed thinner than usual at many other spots. Attitudes began to change, however, as weaknesses proved to be strengths. Williams, in particular, played flawlessly. In a victory over Michigan State, he completed 13 of 16 passes, including several clutch fourth-down throws.

Leons final college game was the focus of the sports world. He had yet to leave the field on the short end of a losing score, and the Irish had a chance to nail down a third national championship. Notre Dame played Southern Methodist, whose star back, Doak Walker, was the reigning Heisman Trophy winner. He was also injured and unable to play. But his replacement, Kyle Rote, was spectacular, scoring three touchdowns against the Irish defense.

With the score knotted 2020 in the final period, Leon was moved to fullback, where he often lined up on important running downs. Leon barreled through the Mustang defense several times to key a drive engineered brilliantly by Williams. Bill Barrett capped the effort with a touchdown that put the Irish up 2720. SMU tried to respond, but Notre Dame stopped the Mustangs.

Leon made a great tackle on Rote to help save the day, but his biggest fourth-quarter contribution had come earlier, when Williams had thrown an incompletion from his own end zone with the Irish pinned against their own goal line on third down. An elderly referee, flashing back to the 1930s, signaled a safety and moved the ball to the 20 yard line, where he instructed Notre Dame to kick to SMU. Leon politely reminded the official that the rule had changed, and that it was simply fourth down. He then huddled the team quickly, and the Irish punted. No one had noticed that they were punting from the 20 when they should have been kicking out of their own end zone. Years later, Leon smiled when reminded of this story. Thats why I was a good captain, he said.

When the whistle blew on the SMU game, Leon had finished his four-year stay in South Bend without a single loss. Few would argue that there was a greater college football dynasty (and outside of John Woodens UCLA basketball team, there is no real competition for the greatest NCAA sports dynasty, period).

In Leons senior season, the Irish outscored their opponents 320 to 93. Overall, the dominance of Leons teams at Notre Dame led many schools to drop the Irish from their football schedules. The Athletic Department responded by reducing the number of scholarships it offered, so other colleges would have a fairer shot at high school talent. Ironically, this led to a downturn in the teams fortunes after Leon left.

Leon closed out his college career with 49 catches for 742 yards and 12 touchdowns. He also scored twice on runs. These stats do not reveal much about his domination of the fieldbut in the context of his time they were nothing short of spectacular.

At seasons end, Leon was named AP Athlete of the Yearfinishing ahead of Jackie Robinson and Sam Sneadand also won the Maxwell Award and Heisman Trophy as the nations top player. He was the top Heisman vote-getter in all five regions, with Charlie Justice of UNC a distant second, more than 700 points behind. It marked just the second time a lineman had captured the Heisman (Yales Larry Kelley took the award in 1936), and it would be the last. In fact, not until Charles Woodson won the Heisman 48 years later did another defender claim the trophy. The ceremony, meanwhile, wasn't the only highlight of Leon's trip to New York. While in the Big Apple to pick up the hardware, he also ate breakfast with Cardinal Spellman.

President of the Class of 1950, Leon graduated from Notre Dame with a degree in mechanical engineering. In the rough and tumble, low-paying early days of pro football, it would not have been surprising to see him quit the game and move on with his life. Leon, however, used this leverage as a bargaining position with the Detroit Lions, who selected him with the top overall pick in the first round of the 1950 draft. Once he worked out a contract and secured a respectable off-season job, Leon joined the Lions, who were coming off a 48 season.

Detroits coach, Bo McMillin, was in his third and final season with the team. The Lions had struggled in the postwar years, but McMillin was starting to assemble some of the pieces of the defensive puzzle, including mountainous middle guard Les Bingaman, and defensive backs Jim Smith and Don Doll. Leon played a fair amount of defensive end as a rookie and performed well enough to become a starter at the position the following season.

Leon was part of an incoming group that would transform the Lions. The '50 draft had also yielded Doak Walker and lineman Thurman McGraw. The dissolution of the AAFC had enabled the Lions to pick up guard Lou Creekmur and running back Bob Horschenmeyer. Cloyce Box, a converted halfback, had been with Detroit in 1949, but was moved to receiver in his second year. The biggest addition was the acquisition of quarterback Bobby Layne, purchased during a housecleaning by the financially strapped New York Yankees football club.

The Lions opened the season with a 457 pasting of the Green Bay Packers. They would top the 40-point plateau twice more that year. On Friday night, September 29th, Leon experienced defeat on a football field for the first time. The Yanks beat them in New York, 44-21.

The Lions finished with a 66 record, but put on a great show for the fans all season long. Layne, a wild man off the field, was a great leader and performer on Sundays. He led the league with 336 passing attempts and 2,323 yards. Thirty-one of those passes went Leons way. He combined with Walker and Box for 116 catches.

In 1951, Detroit fans welcomed Buddy Parker back to town, this time to coach the team. In the 1935 Championship Game, he had scored a touchdown and intercepted a pass. Known as a resourceful player in the NFL during the 1930s, Parker was also a clever coach. He molded the Detroit gameplan to the talent he inherited, and almost instantly, the Lions became a championship contender.

They also became the leagues loosest clubwhere McMillin had been something of a taskmaster, Parker was willing to let the good times roll. One of his first moves was to make Leon his fulltime defensive end on the right side. Most NFL teams had moved to a platoon system at this point, but if there was ever anyone born to be a two-way player, it was Leon. He was a monster on defense, earning All-Pro honors. He also led the Lions with 35 receptions, filling the shoes of Box, who missed the year due to military service. Leons 12 touchdown catches in 51 placed him second to Elroy Hirsch of the Los Angeles Rams, who score 17 times.

The hard-living Lions kept pace with the glamorous Rams all season long, and Detroit suddenly rediscovered its football team. Attendance doubled despite a 231 home mark. The Lions were road warriors, upending the Chicago Bears and Rams in their home parks. They missed the playoffs, however, when they lost the seasons final game in San Francisco.

The Lions had a big-play defense in 1952. Week after week, they made crucial stops in close games or picked off fourth-quarter passes to seal their victims fates. The secondary now included young playmakers Jack Christiansen and Yale Lary. Both were also superb special teams performers. Another addition to the team was Leons co-captain at South Bend, Jim Martin. Drafted by the Cleveland Browns, he would play the rest of his career with the Lions.

As for Leon, his defensive days were essentially over at this point. Parker returned him to fulltime pass-catching duty, and he teamed with Box to give the Lions a formidable one-two receiving punch. Functioning as a prototype possession receiver, Leon snagged 32 passes, while Box was the deep threat, catching 42 balls and leading the NFL with 15 touchdowns.

Leons role in the Detroit offense was quite similar to that of a modern tight end. In the 1940s and early 1950s, ends were typically blockers or pass receivers, but rarely both, at least not on an All-Pro level. Leons then-freakish combination of size, speed and skill intrigued Parker, who laid the very early foundation of tight end play in the NFL with his use of Leon . A few years after Leon retired, Vince Lombardi began using hulking Ron Kramer as a traditional tight end in the Packer offense, and Mike Ditka became a star for George Halas in Chicago.

The Lions faced the Browns in the NFL Championship, and with the exception of a second-half drive by Otto Graham & Co., they stymied the Cleveland offense all day. Detroit took a 70 lead on a quarterback sneak by Layne, and extended that lead to 140 after Leon helped open up a huge hole for Walker, who scampered 67 yards for a touchdown. The Browns played sloppy football and paid the price, losing 177. The Lions were champions for the first time since 1935.

In 1953, Detroit outlasted the Rams and 49ers to repeat as conference champs, thanks to their returning veterans and an infusion of young talent that included linebacker Joe Schmidt. The Lions needed to win their final six games and did, keeping each opponent to two touchdowns or less. The offense combined the grinding ball carrying of Horschenmeyer, Walker and rookie Gene Gedman with Laynes breathtaking passing. Opponents never knew when the wily veteran would crank out a long bomb, or who would catch it. Five different receivers averaged more than 15 yards per reception. Leon was second on the team with 25 catches (at 19 yards per) and led all Lions with seven TD grabs.

In a championship repeat, the Detroit defense forced the Browns into early turnovers, but Cleveland regrouped to take a 1610 lead with five minutes left in the game. Layne marched the team down the field, connecting on three passes with little-used Jim Doranbest known as a defensive endwho scored the tying touchdown. Walker booted the extra point for the 1716 lead. Rookie defensive back Carl Karilivacz then intercepted Graham on Clevelands ensuing possession to finish off the Browns.

The Lions made it three straight conference titles in 1954, holding off a late charge by the Bears to win the West with a 921 record. This was Leons last season as a starting end. He caught 24 passes but never reached the end zone. His blocking proved critical, however, as the Lions gave a lot of carries to rookies Bill Bowman and Lew Carpenter, who frequently spelled Walker and Horschenmeyer. As a foursome, this group amassed nearly 1,500 yards. Layne, meanwhile, ended the year as the NFLs top-ranked passer. Dorne Dibble was his favorite target. The defense again keyed Detroits success, with the secondarynow dubbed Chriss Crew after Christiansenpicking off 23 passes.

Detroits magical run ended in a late December meeting with the Browns. Layne threw six interceptions and the Lions fumbled three times as they went down in flames, 5610. Detroit was in the game as late as the second quarter, when the score was 1410, but Cleveland scored 42 unanswered points to rule the day. Leon played the entire game, contributing one catch for 19 yards.

The 1955 season found Doran, Jug Girard and rookie Dave Middleton taking most of the snaps at the receiver position. Leon functioned primarily as a blocker when he lined up next to the tackles. Most of his work came as the teams second-string fullback behind Carpenter. Leon ran the ball 35 times and made the tacklers pay, averaging a team-best 4.5 yards per carry. This good work was done entirely in vain, however, as Detroit started the year with six straight losses and tumbled into the cellar with a 3¬9 record. The defense was devastated by the retirement of Bingaman, while Layne played all year with a shoulder injured in an off-season horse-riding incident.

Leon became Detroits primary fullback in 1956, leading the way for Gedman and rookie Hopalong Cassady. Walker and Horschenmeyer had both hung up their jerseys after the miserable '55 campaign, but Leon kept chugging along. Detroit fans cheered as he buried would-be tacklers with his blocking and once again led the team with a 4.6 yards per carry average. He finished the year with 348 rushing yards, 116 receiving yards and six touchdowns.

The Lions rebounded with a 93 record, but the Bears edged them at 921. The conference was Detroits for the taking after a 4210 hammering of Chicago with three games to go. The Bears returned the favor on the final Sunday, however, knocking Layne out of the game and winning 3821.

Leon played his final NFL season in 1957. The Lions acquired John Henry Johnson, who became the teams starting fullback and leading rusher. Leon saw mostly blocking duty and gained just 99 yards on 24 carries. He also caught four passes to give him 174 for his career.

The year is best remembered for coach Parkers stunning resignation during training camp. Assistant George Wilson took over and instituted a two-quarterback system with Layne and ex-Packer Tobin Rote. The Lions made a late surge to tie the 49ers for the Western crown, then beat them in the ensuing playoff. San Francisco played a flawless first half, taking a 247 lead into the locker room at intermission. The 49ers then made a critical mistake, celebrating so loudly that the infuriated Lions could clearly hear them. Detroit scratched its way back into the game and shut down the San Francisco offense in the fourth quarter to win 3127.

The Lions faced the Browns for the NFL Championship once again. With the 5610 humiliation of 1954 still fresh in their minds, they demolished their eastern rivals 5914. With Layne sidelined with a broken leg, Rote passed for 280 yards and four touchdowns. Leon played sparingly in the victory, but it was still a great way to go out. He ended his career one receiving yard short of 2,500, rushed for 612 yards (and a 4.3 per carry average), and scored a total of 32 touchdowns for the Lions. He also intercepted four passes.

After football, Leon put his engineering and business skills to work, running several successful businesses related to the automobile and trucking industry, including one that manufactured tire-balancing equipment. In 1973, he was voted in the National Football Foundation Hall of Fame. Also during the 1970s, he spearheaded a fund providing scholarship assistance for the children of Notre Dame letter-winners. His own son, Kevin, played for the Irish at the time, and was a member of the 1977 national championship squad.

In all, Leon and his wife, Lois, had six children: Leon Jr., Bill, Marty, Kevin, Judd, and Maria. Three are Notre Dame grads. The family lived in the Detroit suburb of Birmingham. Lois passed away in 1998.

In 2000, Leon decided to put his Heisman Trophy up for auction, with the proceeds earmarked for the education of his 14 grandchildren. Thanks to family genetics, at least one of those kids needed no help with tuition. Jenna Hart was one of the most sought after womens volleyball recruits in 2007. She signed with Fordham University. She stands six feet tall and is a member of the National Honor Societya definite chip off the old block. Another grandchild, Brendan Hart, played tight end for Notre Dame from 2000 to 2003, making the team as a walk-on.

After watching Brendan play in Notre Dames thrilling 2523 victory over Michigan in September of 2002, Leon was admitted to St. Joseph Regional Medical Center. He had suffered from heart and prostate problems for some time. Eight days later he passed away at the age of 73.

Leon Hart remained thoughtful and outspoken to the end. He lamented what he perceived as a lack of toughness in todays players, and often wondered aloud why pro and college teams needed 12 to 15 coaches when he won three national championships playing for a staff of six.