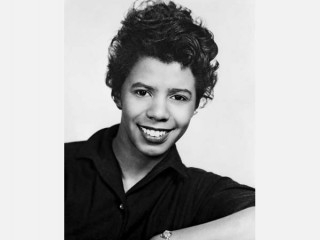

Lorraine Hansberry biography

Date of birth : 1930-05-19

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Chicago, Illinois, USA

Nationality : American

Category : Arts and Entertainment

Last modified : 2010-07-13

Credited as : Playwright, ,

14 votes so far

Lorraine Hansberry is an African American writer who achieved a number of important firsts during her short life; she was the first black woman to write a play that was produced on Broadway as well as the first black and youngest woman to win the New York Drama Critics Circle Award. This play, titled A Raisin in the Sun, was also the first Broadway play to be directed by an African American--Lloyd Richards--in over fifty years. During her short life, Hansberry completed two plays and left three others uncompleted; a sixth piece would be assembled after her death from excerpts from her writings. Although she only lived until the age of thirty-four, her achievements helped to pave the way for other African Americans who wanted their plays to be produced.

Hansberry was born into a middle class family on the South side of Chicago in 1930. Her father was a successful real estate broker, and when Hansberry was eight he deliberately violated the city's covenant laws by moving into a segregated white neighborhood. With the help of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored Persons (NAACP), Hansberry's father took his case to the Illinois Supreme Court. The court ruled that the laws, which sanctioned housing discrimination, were unconstitutional. During the trial, white neighbors harassed the Hansberry family. On one occasion, a brick that was thrown through their home's living room window barely missed Hansberry's head. Because her parents were so dedicated to the struggle for civil rights, Hansberry learned about sacrifice and injustice at an early age.

Even though he won a victory in court, Hansberry's father was disappointed that his legal victory brought about little change. He had plans to move his family to Mexico, but he died in 1945. Although her father supposedly died of a cerebral hemorrhage, Hansberry would later remark that "American racism helped kill him."

Hansberry first became interested in theater when she was in high school. In 1948 she began attending the University of Wisconsin, where she spent two years. It was there that she took a course in stage design and saw the plays of Henrik Ibsen and Sean O'Casey for the first time. Later, she studied painting at the Art Institute of Chicago (then Roosevelt College) and in Guadalajara, Mexico. She moved to New York in 1950 and worked at a number of jobs while she wrote short stories and plays. She worked as an associate editor and reporter for Paul Robeson's monthly Freedom magazine, and she also became politically active. She was on a picket line protesting discrimination at New York University when she met Robert Nemiroff, a white man who became a songwriter and producer after the couple married in 1953. Nemiroff encouraged Hansberry in her writing and even went so far as to salvage discarded pages from the wastebasket near her typewriter.

A First in Theater

Although she had been working on three uncompleted plays and an unfinished semiautobiographical novel before she began working on A Raisin in the Sun, the play was to be Hansberry's first completed work. In an interview with the New York Times, quoted in an essay by Michael Adams in the Dictionary of Literary Biography, Hansberry talked about what inspired her to write this play. "One night, after seeing a play I won't mention," she said, "I suddenly became disgusted with a whole body of material about Negroes. Cardboard characters. Cute dialect bits. Or hip-swinging musicals from exotic scores." She channeled her anger into her writing. One night in 1957, while Hansberry and Nemiroff were entertaining their friends Burt D'Lugoff and Philip Rose, they read the play aloud. To their surprise, Rose announced the next morning that he would like to produce the play on Broadway.

A Raisin in the Sun is the story of a black family living in a run-down apartment in Chicago. The characters include Walter Lee, a chauffeur, his wife Ruth, who works occasionally as a maid, their ten-year-old son Travis, Walter's mother Lena, and his sister Beneatha, a college student. All members of the family are unhappy with their lives, but they look forward to some improvements because of a ten-thousand-dollar life insurance payment they will be receiving on the death of Walter's father. The family members discuss how to spend the money: Walter wants to use the money to buy a liquor store, Beneatha wants to use the money for her medical school tuition, and Lena wants to buy a nice house in an all-white neighborhood. Lena makes a $3,500 down-payment on the house and puts $3,500 in the bank for Walter and $3,500 for Beneatha. But Walter gives the money to his business partner, who runs away with it and shatters the family's dreams. To make matters worse, Walter agrees to accept money from a representative of the white neighborhood in exchange for not moving there. He later realizes that he would be sacrificing his manhood if he accepted the money, and he rejects the offer. At the end of the novel, the family realizes that they will still have to struggle, but that they love each other despite their weaknesses.

The title of A Raisin in the Sun comes from a question posed by Langston Hughes in his 1951 poem "Harlem:"

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun? Or fester like a sore-- And then run? Does it stink like rotten meat? Or crusty and sugar over-- like a syrupy sweet?

Maybe it just sags like a heavy load.

Or does it explode?

A Raisin in the Sun was a solid success in tryouts all over the country, and it made its Broadway debut on March 11, 1959, at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre. In June of that year, Hansberry was named the "most promising playwright" of the season. A Raisin in the Sun would become the longest- running black play in Broadway's history.

A Raisin in the Sun enjoyed immense popularity because it explored a universal theme--the search for freedom and a better life. Writing in Commentary, Gerald Weales pointed out that "Walter Lee's difficulty ... is that he has accepted the American myth of success at its face value, that he is trapped, as Willy Loman [in Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman] was trapped by a false dream. In planting so indigenous an image at the center of her play, Miss Hansberry has come as close as possible to what she intended--a play about Negroes which is not simply a Negro play."

Other critics agreed with Weales' assessment. Writing in Saturday Review, Henry Hewes declared that in Hansberry's A Raisin in the Sun "we have at last a play that deals with real people." Critic Harold Clurman, in the Nation, noted that "A Raisin in the Sun is authentic: it is a portrait of the aspirations, anxieties, ambitions, and contradictory pressures affecting humble Negro fold in an American big city." New York Times critic Brooks Atkinson concurred, stating that "A Raisin in the Sun has vigor as well as veracity."

The play's original run on Broadway lasted for nineteen months and a total of 530 performances. Hansberry sold the movie rights of A Raisin in the Sun to Columbia Pictures in 1959, and in 1960 she wrote two screenplays. In the new screenplays, Hansberry added some provocative new scenes that pointed out problems that African Americans were facing at the time. However, Columbia allowed none of these new scenes or any new material to appear in the film version, which was basically a shortened version of the play. In 1961 the film version of the drama was released, starring Sidney Poitier as Walter Lee and Claudia McNeil as Mama. For the film, Hansberry won a special award at the Cannes Film Festival, and her screenplay was nominated for a Screen Writers Guild Award.

Entering the Limelight

The success of A Raisin in the Sun made Hansberry an instant celebrity, and she found herself enjoying it. She appeared on countless radio and television talk shows and attempted to answer letters from almost everyone who wrote to her. She was fun-loving and would often reply whimsically to questions, but she never shied away from a serious question and could cause discomfort for even hardened interviewers such as Mike Wallace.

In 1960 Hansberry faced censorship again when producer-director Dore Schary asked her to write a play on slavery for television. The play was to be the first in a series of five dramas to be written by leading playwrights to commemorate the centennial of the Civil War. When Schary told the management of NBC that he had asked a black playwright to create a drama about slavery, they asked what her attitude was toward it. When he learned that this question was not a joke, Schary realized that the project would not survive. It was later cancelled, but Hansberry used the material she had developed in a play she called The Drinking Gourd. This work was published posthumously in 1972, and scenes from it were included in another play, To Be Young, Gifted, and Black.

It is believed that The Drinking Gourd was inspired in part by stories told to Hansberry by her mother and grandmother. Hansberry's grandfather, who was a slave, escaped from his master and hid in the Kentucky hills while his mother brought food to him. The play was also influenced by the enormous amount of reading that Hansberry did on the topic of slavery before and after she was asked to write the play. The result is a disturbing but strongly unified drama about sympathetic characters at three social levels-- slave owners, poor whites, and slaves--each caught in a dehumanizing chain of events that threatens to destroy them all.

Hiram Sweet is the slave master, and Hannibal, his mother Rissa, and his sweetheart Sarah are slaves. Sweet keeps the slaves in a state of ignorance and forces them to perform hard, unrewarding labor. Hannibal responds by malingering and doing only half of the work that his master wants him to complete in the cotton fields. He also talks the master's younger son, Tommy, into teaching him to read. Meanwhile, Rissa, who has worked with Sweet since he started the plantation, tries to use her position as cook and quasi-confidante to pressure Sweet to take her son out of the fields so that he will not continue to be defiant. Although work in the fields is strenuous, Rissa and Sarah know that the life of a house slave is also hard. Finally, their situation becomes so difficult that the three decide they can no longer tolerate it and must flee no matter what the risk.

The situation of Zeb Dudley, a poor white man, is not much better. Because he has only a small farm and no slaves, he is not able to compete with the big plantations. He must decide whether to leave the South and try to make a home in the West or take a job as an overseer so that his children can eat. He decides to become an overseer and is forced to commit brutal acts, such as putting out the eyes of Hannibal because he learned to read.

Even Sweet finds that slavery forces him to do things that are damaging spiritually and physically. He once thought of himself as a humane master because his slaves only worked nine-and-a-half-hour days. Now, declining market prices and diminishing yields force him to make the slaves work longer and harder, which, in some cases, will probably lead to death. Sweet also sees that the continued competition between the North and the South will eventually lead to a war that the South cannot win. He becomes so worried that his health worsens and he is forced to turn control of the plantation over to his ruthless son Everett. Everett sets out to undermine everything that Sweet has done. He is the one who makes the decision to blind Hannibal, but it is Sweet who pays the price for it--Rissa blames Sweet for the attack and will not come to his rescue when he collapses from tension. At the end of the play, the Civil War is beginning and the narrator reveals that he has decided to fight for the North because "it is possible that slavery might destroy itself ... it is more possible that it would destroy these United States first."

In 1961 Hansberry and her husband moved from Greenwich Village to a house in Croton-on-Hudson, a tranquil wooded area of New York State within commuting distance of New York City. From this peaceful place, Hansberry was able to balance her public and private commitments. She continued to be politically active: in 1962 she mobilized support for the Student Non-Violent Coordination Committee (SNCC) in its struggle against segregation in the South; she spoke against the House Un-American Activities Committee and the Cuban missile crisis; and she wrote What Use Are Flowers?, a play about life after an atomic war.

At Work until the End

In 1963 Hansberry was diagnosed with cancer. Undaunted, she continued to write and to work for various causes. A scene from Les Blancs, a play that was in progress, was staged at the Actors Studio Writers Workshop. In May she joined a meeting of several prominent African Americans and a few whites who met with Attorney General Robert Kennedy to discuss the racial crisis. At this time, Kennedy was unable to understand or comprehend the urgency of blacks, and the meeting was emotionally charged. In June Hansberry chaired a meeting in Croton-on-Hudson to raise money for the SNCC. Five days later, she underwent an unsuccessful cancer operation.

In 1964 the SNCC prepared a book titled The Movement: Documentary of a Struggle for Equality. The book contained photos of horrifying and distressing aspects of the black experience in America, including lynchings, savagely beaten demonstrators, and substandard housing. The photographs were coupled with a sharply worded text written by Hansberry.

Hansberry's marriage to Nemiroff ended in 1964, but she continued to work with him, and the two saw each other daily until her death. Even as she underwent radiation and chemotherapy treatments, Hansberry worked on a number of projects, including The Sign in Sidney Brustein's Window, which was being produced by Nemiroff and Burton D'Lugoff. Hansberry attended the opening of the play at the Longacre Theater.

Beside A Raisin in the Sun, The Sign in Sidney Brustein's Window is Hansberry's only other completed play. It was a commercial and critical failure, but it attracted a group of passionate supporters. The lead character, Sidney Brustein, is a liberal but apolitical man who is drawn into action when he agrees to work for a reform candidate in a city election. Sidney soon discovers that people can have good ideals but may be personally corrupt or weak in ways that invalidate their theoretical commitment. Some of the characters include a black friend of Sidney's who is prejudiced and a homosexual friend who is sexually manipulative. Writing in Contemporary Literature: American Dramatists, Gerald M. Berkowitz remarked that The Sign in Sidney Brustein's Window "is excessively talky, and secondary characters are either underwritten ... or overwritten.... Still, it is a failure of accomplishment rather than of conception and one can see the core of a play that might have been stronger had Hansberry (who was terminally ill at the time of production) been able to work on it more."

For the most part, the initial reviews of The Sign in Sidney Brustein's Window were not positive. Walter Kerr, for example, writing in the New York Herald Tribune, stated that the problems Brustein encounters "are much too small, finicky and familiar to serve as a carryall." Generally, mixed reviews mean instant death for a Broadway play, but a large number of Hansberry's supporters contributed time, money, and publicity to keep the play running for one hundred and one performances. The Sign in Sidney Brustein's Window ran until the Hansberry's death on January 12, 1965.

Many critics were disappointed because The Sign in Sidney Brustein's Window, which is set in the Greenwich Village flat of a white man, was so different from A Raisin in the Sun. However, Hansberry refused to be limited in her writing, and at the time of her death she was working on a wide range of projects, including an opera about the Haitian revolutionary Toussaint L'Ouverture; a musical based on the Laughing Boy, a novel about the Navajos by Oliver LaFarge; and a drama about the ancient Egyptian ruler Akhnaton.

During the last year and a half of her life, Hansberry also spent considerable time working on Les Blancs, a play about Africa. She also worked on a play about the eighteenth-century feminist Mary Wollstonecraft. On May 1, 1964, she was released from the hospital to deliver a speech to the winners of the United Negro College Fund writing contest, for which she first coined the phrase "To be young, gifted, and Black." She did not finish Les Blancs, but left extensive notes and held long discussions with Nemiroff so that he could finish the play after she died. Nemiroff did finish the play, and it opened at the Longacre Theater on November 15, 1970. It received mixed reviews and closed after forty-seven performances.

Les Blancs is the story of the radicalizing of a white reporter, Charles Morris, and a black intellectual, Tshembe Matoseh. Morris travels to the mythical African country of Zalembe to meet the leader of the country, Reverend Torvald Neilsen. He learns that Neilsen acts as a Great White Father caring for his irresponsible black children. Morris then comes to the conclusion that only a violent revolution will help to liberate the country. The revolution does occur, and Matoseh is forced to kill his own brother.

When Hansberry died, six hundred people attended her funeral, and Paul Robeson delivered the eulogy. Nemiroff remained dedicated to Hansberry and her work. He was appointed her literary executor, and he collected her writings and words and presented them in the autobiographical montage To Be Young, Gifted, and Black. He also edited and published her three unfinished plays--Les Blanc, The Drinking Gourd, and What Use Are Flowers? "It's true that there's a great deal of pain for me in this," Nemiroff told Arlynn Nellhause of the Denver Post, "but there's also a great deal of satisfaction." To Be Young, Gifted, and Black was made into a play that ran Off-Broadway in 1969.

C. W. E. Bigsby, writing in Confrontation and Commitment: A Study of Contemporary American Drama, 1959-66, stated that "Hansberry's death at the age of thirty-four has robbed the theatre of the one Negro dramatist who has demonstrated her ability to transcend parochialism and social bitterness." Clive Barnes, in the New York Times, described Hansberry as "a master of the dramatic confrontation." According to Jeanne Noble, writing in Beautiful, Also, Are the Souls of My Black Sisters, among Hansberry's last words were, "I think when I get my health back I will go into the South to find out what kind of revolutionary I am." Although she never got the chance, Hansberry contributed to the civil rights movement in the United States by inspiring readers and theatergoers in both her own generation and those that have followed.

AWARDS

New York Drama Critics Circle Award for Best American Play, 1959, for A Raisin in the Sun; named "most promising playwright" of the season, Variety, 1959; Cannes Film Festival special award and Screen Writers Guild nomination, both 1961, both for screenplay A Raisin in the Sun.

CAREER

Playwright. Worked variously as a clerk in a department store, a tag girl in a fur shop, an aide to a theatrical producer, and as a waitress, hostess, and cashier in a restaurant in Greenwich Village run by the family of Robert Nemiroff; associate editor, Freedom (monthly magazine), 1952-53.

WORKS

Plays

* A Raisin in the Sun (three-act; produced on Broadway, 1959; also see below), Random House, 1959, with introduction by Robert Nemiroff, Vintage, 1994.

* The Sign in Sidney Brustein's Window (three-act; produced on Broadway, 1964), Random House, 1965.

* Les Blancs (two-act; produced on Broadway, 1970), Hart Stenographic Bureau, 1966, published as Lorraine Hansberry's "Les Blancs", adapted by Robert Nemiroff, S. French (New York City), 1972.

* To Be Young, Gifted, and Black: A Portrait of Lorraine Hansberry in Her Own Words (produced Off-Broadway, 1969), illustrated by Hansberry, edited by Robert Nemiroff, introduction by James Baldwin, Prentice-Hall, 1969, adapted by Nemiroff, S. French, 1971.

* Les Blancs: The Collected Last Plays of Lorraine Hansberry (includes The Drinking Gourd and What Use Are Flowers?), edited by Robert Nemiroff, Random House, 1972, published as Lorraine Hansberry: The Collected Last Plays, New American Library, 1983.

* A Raisin in the Sun (expanded twenty-fifth anniversary edition) [and] The Sign in Sidney Brustein's Window, New American Library, 1987.

Other

* A Raisin in the Sun (screenplay), Columbia, 1960.

* (Author of text) The Movement: Documentary of a Struggle for Equality (collection of photographs), Simon & Schuster, 1964, published as A Matter of Colour: Documentary of the Struggle for Racial Equality in the U.S.A., Penguin (London), 1965.

* Lorraine Hansberry Speaks Out: Art and the Black Revolution (recording), Caedmon, 1972.

Other Works

* Contributor to anthologies, including American Playwrights on Drama, 1965; Three Negro Plays, Penguin, 1969; and Black Titan: W. E. B. Du Bois. Also contributor to periodicals, including Negro Digest, Freedomways, Village Voice, and Theatre Arts.

* Adaptations: A musical version of The Sign in Sidney Brustein's Window was produced on Broadway in 1972; Raisin, a musical version of A Raisin in the Sun, was produced on Broadway in 1973. A Raisin in the Sun was recorded on audiocassette, Caedmon, 1972.