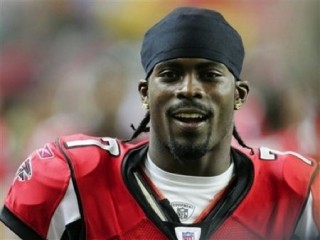

Michael Vick biography

Date of birth : 1980-06-26

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Newport News, Virginia, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2010-08-20

Credited as : Football player NFL, quarterback for the Atlanta Falcons , Super Bowl

1 votes so far

Michael Dwayne Vick was born on June 26, 1980, in Newport News, Virginia. Located at the southernmost tip of the peninsula that divides the James River and Chesapeake Bay—and across the water from Norfolk—his hometown had seen its share of good times and bad. Like most port cities, Newport News fell on hard times in the 1970s and 80s. When Michael entered the world, the city was best known for producing drug dealers and gang members. Serious trouble, the kind that turned many young men into statistics, lurked around most corners in his neighborhood.

Michael's family situation was less than ideal. His mother, Brenda Vick, was 16 when she became pregnant with him. His father, Michael Boddie, was just a year older. Already the parents of a girl, Christina, they did not marry for another five years—at which point two more children, Marcus and Courtney, had arrived.

Boddie was away more often than he was home during his children's formative years. After spending nearly three years in the Army, he bounced from one job to another. Eventually he found steady work in the Newport News shipyards as a sandblaster and spray-painter. His days started early and ended after dark.

The responsibility of raising Michael and his siblings fell to Brenda. She became their savior. In fact, all the kids chose to use her last name. With help from her parents, Brenda ran a tight ship. The family lived in the Ridley Circle housing project on the city's east side. She kept the cramped three-bedroom apartment immaculate. Brenda worked at a KMart, spending every spare dollar she earned on the kids.

Despite his meager surroundings, Michael (who went by “Ookie” back then) was an upbeat, polite and focused child. Thanks in part to his father, football was his passion. Michael was three when Boddie—nicknamed “Bullet” for his blinding speed during his playing days on the gridiron—began teaching him the fundamentals of throwing the pigskin. Interestingly, the first time Michael picked up a football, he used his left hand, even though he did everything else with his right (which is still true today).

.The youngster also learned a lot from Aaron Brooks. A cousin four years Michael's senior, Brooks who would go on to successful NFL career. His best season came in 2003 with the New Orleans Saints when he threw for 3,546 yards and 24 scores. As a kid, Michael followed Brooks wherever he went, including the Hampton Roads Boys and Girls Club.

James Hagman, the club's unit director, remembered the pair for their hard work and dedication. So did James “Poo” Johnson, who coached the club's football team. As a 13-year-old, Michael often called Johnson and asked if he would work with him one-on-one, mostly on fundamentals. It was Johnson who later advised Michael to hit the weight room and add muscle to his sinewy frame—a crucial moment in his football life. Michael credits leg exercises with turning him into a world-class open-field runner.

As a grade schooler, Michael also showed tremendous promise in baseball and basketball. By junior high, however, his adolescent angst got the best of him, and he became a disciplinary problem for his teachers. His mother pushed him to get involved with an after-school activity. Michael chose football and basically gave up all other sports in the ninth grade. He modeled himself after Steve Young, another lefty who could beat you with his arm or his legs.

Michael entered Ferguson High School in the fall of 1994. When the school was shut down in 1996, he transferred to Warwick High School. Brooks, now at the University of Virginia, had graduated the previous spring. He told Michael to try out for Warwick's football team, convincing him that he had a shot at the varsity.

The school's coach, Tommy Reamon, was happy to welcome Michael aboard. Reamon knew a little about playing football at a high level. After a storied career as a running back at the University of Missouri in the early 1970s, he went on to stardom in the World Football League. Reamon was named league MVP in 1975. A year later, he hooked on with the Kansas City Chiefs. Reamon gained 450 yards from scrimmage and scored five touchdowns in 1976, and then called it quits.

Reamon liked what he saw from Michael, but felt the teenager would be best served by a year on the junior varsity. In Michael's first six JV games, he tossed 20 touchdown passes. Meanwhile, Warwick's varsity was struggling. Searching for a spark, Reamon moved his starting quarterback to wide receiver and promoted Michael to the varsity. In his second start, he really aired it out, throwing for 433 yards on just 13 completions.

Over the next three years, Michael's reputation grew. Reamon sent him to football camps every summer and tutored him privately. Knowing that Warwick wasn't particularly big or strong across the line, he encouraged Michael to improvise on offense. The freedom helped him to develop his trademark style.

Going into his senior season, SuperPrep and PrepStar named Michael a pre-season All-America. Despite the accolades, he was overshadowed by other schoolboy phenoms in his area. Ronald Curry, who starred at nearby Hampton High School, was regarded as the best quarterback prospect in the country. Also making headlines was a kid named Allen Iverson, who was almost as good a point guard as he was a quarterback.

It didn't help either that Warwick never really challenged for the state championship. During Michael's career as a starter, the Raiders went just 20-13. Four times he faced Hampton, and each time Curry led his team to victory.

By the end of 1997, Michael was considered among the top five high school signal callers in the country. In his four varsity seasons at Warwick, he threw for 4,846 yards and 43 touchdowns, and ran for another 1,048 yards and 18 TDs. Michael was a playmaker, pure and simple. With the right tutoring and teammates, no one doubted he had the talent to become a grat college quarterback. College coaches nationwide recruited him. Eventually, Michael narrowed his choices down to Syracuse and Virginia Tech.

Initially, Michael leaned toward the Orangemen. A fan of the school since childhood, he knew all about coach Paul Pasqualoni's option-pass attack and liked that the school had established a legacy of talented black quarterbacks. In fact, he and Donovan McNabb had become friends during his visit to the campus the January after his junior season at Warwick. Pasqualoni wooed Michael by promising that he could wear McNabb's #5.

Reamon, however, felt Virginia Tech was a better fit. He sold Michael on the school's proximity to family and friends, and noted that Troy Nunes, another highly touted quarterback, had already committed to Syracuse. Reamon also believed that the freshman needed time to develop, and Virginia Tech coach Frank Beamer planned to redshirt him. Michael listened to his high school coach and became a Hokie.

ON THE RISE

Michael arrived at Virginia Tech's campus in Blacksburg in the summer of 1998. He joined a talented recruiting class that included linebacker Jake Houseright and running back Lee Suggs. In the preseason, Michael got some snaps with the first team, but Beamer was true to his word and planted him on the sidelines once the regular campaign began. In what was tabbed a rebuilding year, the Hokies managed a 9-3 record, including a 38-7 rout of Alabama in the Music City Bowl.

Offensive coordinator Rickey Bustle provided valuable guidance to Michael. Early in the season, he got in the teenager's face about the need to work hard every day. Michael heard him loud and clear. Though he briefly considered moving to another position, Michael changed his mind and set out to master Virginia Tech's complicated offense. When he wasn't at practice, he holed up in the film room studying video. On the field, Michael watched starting quarterback Al Clark like a hawk to pick up nuances of the Virginia Tech attack. Though Michael's primary job on game day was was signaling in plays, he approached it with deadly seriousness.

Michael's biggest challenge in his first year of college was homesickness. Most nights were spent on the phone with his mother. He begged Brenda to bring him home, and after the season, she did. Michael recharged his batteries for a couple of days and returned to Blacksburg ready for spring practice.

Michael dazzled his coaches with his physical tools, running the 40 in 4.33 seconds and posting a vertical leap of 40 and 1/2 inches. Both were school records for quarterbacks. Though Michael completed just three of 10 passes in the spring game, teammates marveled at him. When he was on the field, spectacular things always seemed to happen. To a man, the Hokies—long known for their swarming defense—felt they might finally have an offensive force that could lift the team to the next level.

Beamer installed Michael as his starting quarterback in the fall of 1999. The 19-year-old was the youngest player on a veteran unit that had a full arsenal of weapons. Junior Shyrone Stith led a solid group of running backs, senior Ricky Hall was the top receiver, and the line featured five returning starters. The defense also boasted tremendous experience. Seniors Corey Moore and John Engelberger were the best pair of defensive ends in the Big East, and the linebacking crew was fast and hard-hitting.

The campaign began with a 47-0 blowout of James Madison. Michael was sensational in the victory, including a head-over-heels touchdown leap that made highlight clips nationwide. On the play, however, he sprained his left ankle, which forced him out of Virginia Tech's next game, an easy win over Alabama-Birmingham. Michael came back for the team's first test of the season, a home contest against Clemson. Though he threw three interceptions, the Hokies breezed, 31-11.

Michael learned from his performance against the Tigers and played mistake-free football the rest of the way. Virginia Tech's offense became nearly unstoppable. There was a 62-point outburst in a thrashing of Syracuse. Against Rutgers, the Hokies scored on seven of their first eight possessions en route to a 58-20 laugher. In one half of work, Michael accounted for more than 300 yards of total offense and five touchdowns.

Against in-state rival Virginia, Michael racked up 222 yards and a TD on just seven completions. He burned Temple for rushing touchdowns of 53 and 75 yards, and tossed three scoring passes in the regular-season finale against Boston College.

Michael's most memorable moment came against West Virginia. Trailing by a point, the Hokies got the ball on their own 15-yard-line with just over a minute remaining. Michael guided the offense down the field and put Virginia Tech in field goal range. Shayne Graham, the school's all-time leading scorer, booted a 44-yarder for a dramatic 22-20 victory.

The win over the Mountaineers was essential to the Hokies' pursuit of the national championship. Though hurt in the BCS standings by weak competition in the Big East, Beamer's squad stayed in contention by virtue of its perfect record and the way it had dominated opponents. When Tennessee, Penn State, Kansas State, and Nebraska all suffered late-season losses, the undefeated Hokies earned a berth in the Sugar Bowl opposite Florida State—and a shot at the national championship.

As it turned out, the contest in New Orleans was a coronation in more than one way. The Seminoles, who had been ranked #1 the entire season, were looking to finish the job. When Florida State won 46-29, Bobby Bowden got his second championship, cementing his legacy as one of college football's all-time greats.

Meanwhile, Michael, who was trying to become the first freshman quarterback to capture the national title since Oklahoma's Jamelle Holieway in 1985, officially arrived on the national scene. For the season, Michael had passed for 1,840 yards and 12 touchdowns. He added 585 yards and eight scores on the ground. He was named First Team All-America by The Sporting News and took home honors as the Big East's Offensive Player of the Year, the first newcomer in conference history to do so. Michael finished third in the race for the Heisman Trophy, joining Herschel Walker (Georgia, 1980) and Clint Castleberry (Georgia Tech, 1942) as the only freshmen to place that high in the voting

Still, in the Sugar Bowl, many fans saw Michael for the first time, and as always he was impressive. His speed and elusiveness on the artificial turf of the Louisiana Superdome were mind-boggling. When he rallied Virginia Tech from a 21-point deficit to a brief 29-28 lead, he showed the guts and poise of an NFL veteran.

After the season, Michael enjoyed the spoils of celebrity. He won the first-ever Archie Griffin Award as the nation's collegiate MVP and attended the ESPY Awards to collect his trophy as the top college football player. During the festivities, a steady stream of superstars, including Tiger Woods and Mark McGwire, introduced themselves.

All that hype, coupled with all the expectations heaped on Virginia Tech, made preparing for the following year extremely difficult for Michael. The attention he received from the media was staggering. Every day a different magazine, newspaper or television station called for an interview.

Michael worked hard again in the offseason, increasing his 40 time to an eye-popping 4.25 seconds. Coach Beamer did his part to improve the team, bagging receiving prospect Andrae Harrison. The incoming freshman had been Michael's favorite target at Warwick High. The duo hoped to rekindle their old magic, along with help from the team's other wideout, Andre Davis. The offense also counted on the development of two rising stars at tailback, Suggs and Andre Kendrick, who got their chance after Stith opted for the NFL Draft. The pair would share time running behind a reliable offensive line.

Ironically, the worry for Beamer was his defense, which had long been the team's strength. Tech lost eight starters, including six from its front seven. The coach needed big efforts from redshirt freshman Nathaniel Adibi, the linebacking trio of Ben Taylor, Houseright and Nick Sorenson, and an improving secondary paced by Cory Bird.

The Hokies figured to learn a lot about themselves in their first three games, all scheduled within an 11-day span. But the season started on an odd note when their opener against Georgia Tech in the Black Coaches Association Bowl was canceled because of severe weather in Blacksburg. When Virginia Tech took the field a week later versus Akron, the offense exploded for 52 points in an easy win. The Hokies continued to pour it on, averaging 45 points over their first six games.

Though Virginia Tech was 6-0 and ranked in the Top 10, some in the media criticized the team for its cupcake schedule. For the Hokies to remain in the picture for the national championship, they needed big wins against Syracuse and Miami.

Michael also heard some criticism. With opponents focused on containing him, his numbers were down from 1999. The Heisman frontrunner at the start of the season, he began to fall back in the race for the award, as Florida State's Chris Weinke and Oklahoma's Josh Heupel gained support. When Virginia Tech struggled to beat the Orangemen, the pressure increased on Michael and the Hokies.

The season's turning point came against Pittsburgh. In a thrilling 37-34 win, Michael left the game with a badly sprained right ankle. With Miami up next, Virginia Tech's training staff worked to speed the healing process. Their efforts didn't help, and he spent the game on the bench. Without Michael in the lineup, the Hokies got drubbed, 41-21. Virginia Tech dropped like an anchor in the BCS standings, and Michael lost any chance at the Heisman Trophy.

The Hokies ended the year with three straight wins, including a three-touchdown victory over Clemson in the Gator Bowl. Michael, who threw for one score and ran for another, was named the game's MVP. For the season, he completed 87 of 161 passes for 1,234 yards with eight touchdowns and rushed 104 times for 607 yards.

As his sophomore campaign drew to a close, Michael had to decide whether he was going to stay and play, or move to the NFL, where it appeared he might be a first-round pick. This was not a simple decision. Michael may have had all the confidence in the world, but he was still only reading half the field. An option quarterback going pro after just two seasons would be a leap of unprecedented proportions.

Initially, Michael's instincts told him to stay put for one more season. But when it became evident that he would be a Top 5 pick, he began to reconsider. A few weeks in to 2001, he announced that he would forego his final two years at Blacksburg and enter the draft.

Michael's decision caused pro scouts to log a lot of overtime. Normally, a 20-year-old quarterback with 300-something throws under his belt would not even make the NFL radar screen. But Michael's physical skills were off the charts and his potential seemed unlimited. It was hardly a reach to call him the best athlete ever to play quarterback in college. At the same time, there were plenty of questions about him. Would he develop into a topnotch passer? And, if so, how long that process would take?

Michael spent the weeks leading up to the draft surrounded by a hand-picked group of advisors. After signing with a pair of unknown Virginia-based agents, he switched to Andre Colona and the Octagon agency. Michael stayed with his cousin, Aaron Brooks, and sought the advice of All-Pro defensive end Bruce Smith, also a Virginia Tech grad. Octagon brought in Zeke Bratkowski, a former NFL quarterback and coach, to give Michael a head start on what he would likely face on the field in the pros.

The San Diego Chargers, owners of the first pick in the draft, needed a quarterback. The cash-strapped team knew the top selection would command a hefty sum, so as much as they wanted Michael, they determined they could not afford him. Besides, they had their eye on Drew Brees, a probable second-rounder with a smaller price tag. The Chargers dealt their choice to the Falcons in return for an assortment of picks and receiver Tim Dwight. San Diego did eventually get Brees in the second round, while Atlanta landed the biggest prize in the draft with the #1 pick.

A deal got done in a hurry. Michael was eager to begin his pro career, and Atlanta believed it had to score a public relations victory with its fans. In their 35-year history, the Falcons had advanced to the playoffs only six times, and never had they enjoyed back-to-back winning seasons. The franchise's most glorious moment came in 1998, when the team surprised the football world by capturing the NFC championship.

But that highlight was short lived. Atlanta lost to the Denver Broncos in Super Bowl XXXIII, then posted a record of 9-23 over the next two seasons. When the club inked Michael to a six-year contract worth a potential $62 million, including a signing bonus of $15 million, it trumpeted the deal as a major step toward a new era of prosperity. That being said, the Falcons had no intention of rushing Michael. He could expect the NFL version of a redshirt his rookie year.

Atlanta coach Dan Reeves had plenty of experience with talented young quarterbacks. As a Dallas Cowboy in the 1960s, Reeves came up with Roger Staubach and watched as Tom Landry kept him under wraps for years. In Michael, Reeves saw someone with the same extraordinary talent and leadership qualities—perhaps even more than the coach's most famous pupil, John Elway. He wanted to be extremely careful with Michael.

Reeves planned to start Chris Chandler in the '01 season and let Michael observe from the sidelines. But when the rookie impressed in training camp, the coaching staff decided to speed up the learning process and insert Michael in games from time to time. Early in the regular season, Michael got his feet wet without having too much to worry about. In September, he entered a game against the Carolina Panther on a third and goal from the 4-yard-line. On a designed roll out, he raced into the end zone for the first touchdown of his career.

In the weeks that followed, injuries to Chandler forced Michael into the lineup on a more regular basis. In November, he started games against Dallas and the St. Louis Rams. He also saw action in five other contests. For the year, he completed 50 of 113 passes for 785 yards and two touchdowns. Michael also rushed 29 times for 300 yards, good for second on the club. Turnovers, however, were his bugaboo. Though Michael threw only three interceptions, he had trouble holding onto the ball. In a 31-3 loss in Chicago, for example, he fumbled three times.

Atlanta, meanwhile, endured an up-and-down season. A three-game winning streak in November (which began with Michael's first career start) pushed the team's record to 6-4, putting them in position for a run at the playoffs. But the Falcons sputtered over the last six weeks and finished two games under .500.

Michael went into the offseason determined to win Atlanta's starting job. During his rookie campaign he had earned the respect of his teammates with his modesty, punctuality, confidence and hard work. Those qualities didn't change once his first year ended. In addition to improving his reads and mechanics on the field, he sat down with Reeves to come up with a simpler play-calling system for Atlanta's complicated offense.

The Falcons further tried to ease Michael's transition by bolstering the team's rushing attack. They signed scatback Warrick Dunn and drafted burly T.J. Duckett out of Michigan State. By establishing a better ground game, Atlanta hoped to lessen the pressure on Michael when he dropped back to pass.

Part and parcel with that philosophy was strengthening the club's porous defense, the NFL's second worst unit in 2001. Wade Phillips was hired as defensive coordinator, and his innovative 3-4 scheme promised to better utilize Atlanta's undersized-but-speedy front seven. In the secondary, free safety Keith Lyle joined the club, giving corners Ray Buchanan and Ashley Ambrose more freedom to gamble in man-to-man coverage.

The early returns on Atlanta's offseason moves were positive. The Falcons played gutsy, competitive football in 2002. Their defense developed into one of the league's stingier units, and surrender was no longer a part of their vocabulary.

MAKING HIS MARK

Of course, the club's most profound metamorphosis occurred on offense. And so much of that was due to Michael. At an age when most quarterbacks are still in college, he took the first steps toward becoming the bona fide leader of an NFL team. His teammates not only liked him, they looked up to him and trusted him—even those 10 years his senior.

The qualities the Falcons admired in Michael were not hard to understand. He made at least one play a game that defied description, like a mind-blowing 44-yard touchdown run against the Panthers. There was also a 40-yard, against-the-grain bullet against the Green Bay Packers that was the lead of a November '02 story on Michael in USA Today Sports Weekly.

Making these types of jaw-dropping plays that much more amazing was the fact that Michael limited his mistakes. He was not the scatter-armed, deer-in-the-headlights stereotype of the young passer forced too soon into the starting lineup. On the contrary, he went longer than any other QB in 2002 before throwing his first interception. Also, when Michael got on a roll, he carried the whole offense with him—elevating the performance of everyone around him.

That was the case in Atlanta’s 30-24 victory over the Minnesota Vikings in Week 13, when he ran for 173 yards and two touchdowns on just 10 carries. That win appeared to secure a playoff spot for the team and got plenty of people talking about Michael as the league MVP. But the Falcons limped home, dropping three of their last four. Fortunately for them, the New Orleans Saints played even worse. Atlanta backed into the postseason despite a painful loss to the Cleveland Browns on the last Sunday of the regular campaign.

The Falcons’ poor finish banished them to a first-round match-up against the Packers in Green Bay.With snow falling on Lambeau Field almost all game long, Atlanta pulled a major upset, 27-7. The defense was terrific, shutting down Green Bay’s running game and putting constant pressure on Brett Favre. Michael was also fantastic. Though his numbers were just average (117 yards passing and 64 yards rushing), he led the Falcons on scoring drives on their first possessions of the first and third quarters, and made like Houdini on several occasions by escaping what appeared to be certain sacks.

The following week the Falcons fell in Philadelphia to the Eagles. In a defensive struggle, Michael committed a crucial mistake early, throwing an ill-advised pass that was intercepted by Bobby Taylor and returned for a touchdown. While Atlanta’s offense was able to move the ball most of the game, the Eagles stiffened in the red zone and won 20-6.

Michael learned a valuable lesson on that day. The rule for quarterbacks as their teams advance deeper into the NFL playoffs is to make the most of scoring opportunities, avoid errors and manage the clock. While Donovan McNabb posted less impressive stats than Michael, he didn’t take any unnecessary chances and capitalized whenever Atlanta’s defense provided an opening.

In the final analysis, Michael’s first season as a starter was an unqualified success. He threw for nearly 3,000 yards, ran for almost 800 yards and accounted for 24 touchdowns. He was also selected to the Pro Bowl. Most important, however, he showed the ability to win on the road in pressure situations.

Michael faced pressure of a different kind as the 2003 season opened. In training camp, he suffered a fractured fibula in his left leg that threatened to end his year. The injury dealt a severe blow to the Falcons, who some predicted would represent the NFC in the Super Bowl. Without Michael, Atlanta's offense sagged to one of the league's worst. Opponents were able to crowd the line of scrimmage, which made it much easier to clamp down on Dunn and Duckett. Meanwhile, quarterbacks Doug Johnson and Kurt Kittner were awful. The Falcons dropped to the basement in the NFC South, and Reeves came under heavy criticism.

Michael also had his critics. Many questioned his toughness when his recovery dragged on longer than predicted. Even Reeves seemed a bit impatient.

Michael, however, stuck to his guns, saying he wouldn't return until he was sure he could play without any reservation or uncertainty. With Atlanta's record at 2-9, he finally deemed himself fully healthy in late November. In his first game back, a 17-13 loss at Houston, Michael got his feet wet with about two quarters worth of action against the Texans.

A week later in the Georgia Dome, he made his first start of '03, an event that the Falcons treated like a title game. After LeAnn Rimes sang the national anthem (dressed in a Vick jersey), Michael emerged from the tunnel onto the field. The Atlanta faithful erupted in deafening cheers. The left-hander didn't disappoint. Showing almost no rust, Michael passed for 179 yards and rushed for 141 more (the third highest total for the a QB in NFL history) and a touchdown. His presence energized the entire team. The Falcons beat the Panthers in overtime on a 32-yard TD interception by Kevin Mathis.

The remainder of the season was about Michael reacquainting himself with the league. He struggled against the Indianapolis Colts, but rebounded with two solid outings to end the year. In fact, in a 30-28 victory over Tampa Bay Buccaneers on the campaign's second-to-last Sunday, Michael posted a QB rating of 119.2, the second best mark of his career.

The win against Tampa Bay helped the Falcons finish at 5-11—but that record that wasn’t nearly good enough to save Reeves’s job. (Actually, he was fired before the year ended.) In his place, the team hired Jim Mora Jr., formerly San Francisco’s defensive coordinator. He tabbed Greg Knapp and Alex Gibbs as his offensive and defensive coordinators. In the draft, new GM Rick McKay plucked cornerback DeAngelo Hall in the first round of the draft.

In training camp, Michael was slow to pick up Knapp’s version of the West Coast offense. The system—which called for short, quick passes—didn't seem to fit his talents. But the regular season was an entirely different story. The Falcons finished at 11-5 and won their division. Michael was solid, throwing for 2,313 yards and rushing for 902. In all, he accounted for 17 touchdowns.

Atlanta started the 2004 season on a tear, winning its first four games. Michael's performance in Week 3 against division rival St. Louis proved he was comfortable in the new offense. On the day, he completed 14 of 19 passes for 179 yards and one touchdown. He also added 109 yards on 12 carries. Atlanta won easily, 34-17.

Michael enjoyed another big day five weeks later in Denver. In perhaps his finest game as a pro, he threw for 252 yards and two scores, with no interceptions. Michael ran for another 115 yards. He ended the afternoon with a passer rating of 136.1, as Atlanta whipped the Broncos, 41-28.

The Falcons took five of their next six games to seal the AFC South crown. Michael, however, was hurting with a sore shoulder. Hoping to get his quarterback healthy for the playoffs, Mora sat Michael in a loss to the Saints, and then played him for only a couple of series in the season finale against the Seattle Seahawks.

With Atlanta earning a bye in the first round, Michael enjoyed an extra week of rest, which turned out to be awful news for the Rams. After beating Seattle in a Wild Card matchup, St. Louis had no answer for Michael or Atlanta's punishing running game. While Michael passed for only 82 yards, two of his completions went for two touchdowns, and he also rushed for 119 yards, part of a dominant 337-yard ground attack. The Falcons pummeled the Rams, 42-17, and moved on to the NFC Championship Game against the Philadelphia Eagles.

The same question was asked over and over again heading into the contest. Was Michael ready to take his team to the Super Bowl? With the wind howling in Philly, it didn't appear so. The Eagles shut down Dunn and Duckett, and kept Michael in the pocket, where he seemed confused by the variety of blitzes and coverages confronting him. Meanwhile, Donovan McNabb displayed the maturity that Michael still lacked. The Eagles converted several key turnovers into back-breaking scores and cruised to the NFC championship, 27-10.

All in all, the '04 campaign was still a great learning experience for Michael. Though his critics remained, knocking him for being a halfback wearing a quarterback's number, he demonstrated greater ability to think his way through a game.

Atlanta fans had visions of the first back-to-back winning seasons in franchise history in 2005. While the team played well, the Falcons could not overcome stronger division rivals Carolina and Tampa Bay. After an 8–5 start, Atlanta dropped its final three games to finish with a .500 record. Michael had a nice year, starting 15 games and throwing for 2,412 yards. He ran for another 597 and led the NFL at 5.9 yards per carry.

Michael’s ’05 numbers only told part of the story, however. Again, he continued to learn how to turn the extra attention he drew into opportunities for teammates. Dunn, tight end Alge Crumpler, and receiver Michael Jenkins all had superb seasons.

The 2006 campaign saw Michael’s number rise, but his team's fortunes drooped, with just seven victories. Atlanta actually had a chance to make the playoffs in a weak NFC but didn't get the help it needed in the last two weeks. Twice during the year, Michael threw four touchdowns in a game. He finished the season with a career-best 20.

All the progress Michael made in '06 took a back seat the following spring. His name surfaced during a spring dog-fighting probe, and as the facts unfolded, it appeared that he was deeply involved in the bloodsport, along with friends and family members. Since 2001, an outfit known as Bad Newz Kennels had operated on his property. Michael was implicated in everything from wagering on matches to approving the disposal of dogs that lost.

The fallout was swift and unforgiving. Animal rights group protested in front of the Falcons' offices. The media jumped on the story and detailed Michael's willing participation in dog-fighting. The NFL responded by suspending him indefinitely.

Michael issued a public apology and took full responsibility for his actions. But that proved to be no more than a band-aid. In July, he was indicted for animal cruelty. It was also revealed that Michael had failed a drug test when marijuana was detected in his system. To make matter's worse, Michael's finances came under scrutiny. Several banks sued him for $4 million, claiming he defaulted on loans. There was also a chance he could be on the hook for some $20 million he received in signing bonuses from the Falcons.

In the fall of 2007, Michael was sentenced to 23 months in federal prison—a term that some felt was harsh and others believed was completely deserved. Michael surrendered to authorities in November, nearly a month before he was required to do so. His conciliatory actions earned him sympathy from some fans, but many still demonized him as an example of today's spoiled, ungrateful professional athletes.

With Michael's name and reputation tarnished, his future was unclear until the announcement in early August of 2009 that he had inked a contract with the Eagles. Earlier in the summer, Michael had been cleared to rejoin the NFL, although many wondered which team would take on the publicity problems that would accompany his signing.

From a football standpoint, the move made sense for Philadelphia. Donovan McNabb was unlikely to remain healthy for the full 16-game schedule, and Michael would make an intriguing fill-in. In the interim, he might breathe life back into the old halfback option.

Michael was activated from the exempt list on September 15 and added to the Eagles’ active roster. He saw very limited action as McNabb’s backup, but in Week 13, he threw for a touchdown and ran for another against his old team, the Falcons. It was the first time he reached the end zone since 2006. Michael was a solid citizen all year and earned the team’s Courage Award in a unanimous vote—something that meant a lot to him.

The Eagles made the playoffs, and many experts picked them to reach the Super Bowl. The wild card, so to speak, was Michael. How would the team use him in the postseason? Would Philly use him at all? Coach Andy Reid answered that question in a Wild Card meeting with the Cowboys. He called Michael’s number on a second-quarter play—and the result was a 76-yard touchdown pass to rookie Jeremy Maclin. The Eagles got creamed, however, 34-14.

Two days later, Reid confirmed that he planned to stick with McNabb as the starter for the 2010 season. Michael, of course, was hoping he would be allowed to compete for the job.

Is the NFL right to let Michael play? Fans are sharply divided. In Atlanta, they may never forgive him, especially after a radio interview he did in February of 2010. Michael admitted that he wasted his talent while playing for the Falcons, saying that he didn’t work hard enough on the field or off it.

Those who supported Michael’s reinstatement maintain that he has paid for his crimes with his money and freedom, and deserves a chance to show that he is a changed man. Those who wanted Michael banned forever claim that playing in the NFL is not a right. It’s a privilege. And he has forfeited that privilege with his transgressions.

MICHAEL THE PLAYER

Like most quarterbacks known primarily as runners in college, Michael has always wanted to be thought of a passer in the NFL. No one doubts his arm strength—he can throw the ball 80 yards—but he needs to keep improving his touch and accuracy. Michael has shown he can make finesse throws in practice. In the meantime, his arm keeps defenses honest and scattered.

That opens up all sorts of possibilities for Michael's other major weapon, his running ability. Teams flushing him out of the pocket must contend with two uncomfortable facts: Michael is usually the fastest guy on the field, and he has a palette of moves for which most running backs would sell their souls.

That being said, two years away from the game may very well have eroded his skills. What Miochael has left in the tank and how the Eagles will use him will be one of the best-covered stories of 2009 and beyond.

EXTRA

* Michael was the fourth player in Atlanta franchise history to be taken #1 overall pick by the Falcons. The others were Tommy Nobis in 1966, Steve Bartkowski in 1975, and Aundray Bruce in 1988.

* Midway through the 2002 season, Michael’s #7 Falcons jersey was the third-best seller in the country, behind Tom Brady's and Brian Urlacher's.

* Michael led all NFL quarterbacks with six touchdowns in 2005.

* In 2006, Michael had 44 runs of 10 or more yards—the third-best total in the NFL.

* Michael entered the 2007 season with the highest yards-per-carry and most yards per game of any quarterback in history.

* Michael has been trying to do the impossible since he was a toddler. Among his more ill-advised experiments was gluing his eyelids shut at the age of three.

* Michael’s 76-yard touchdown pass against the Cowboys in the 2009 playoffs was the longest of his career.

* Virginia Tech had never gone undefeated in the regular season until its 11-0 campaign in 1999. With the fans in Blacksburg becoming more and more rabid over their team, one industrious cereal maker began producing “Hokie Toasties.” Grocery store owners could barely keep them on the shelves.

* The Colorado Rockies selected Michael in the 30th round of the 2000 baseball draft, even though he hadn’t picked up a baseball or swung a bat since the ninth grade.

* In September of 2002, Virginia Tech retired Michael’s #7 jersey. Under the school’s guidelines, however, the number could still be used. Hotshot running back Kevin Jones wore the number after Michael.

* When Deion Sanders interviewed Michael on a CBS pregame show, he wore the quarterback’s #7 jersey—according to Primetime, the “ultimate sign of respect.”

* To ensure that Michael participated in the team's offseason conditioning program, the Falcons included a clause in the his contract that said he must pay the club $500,000 if he fails to attend 75 percent of Atlanta's spring and summer workouts.

* Michael’s high school coach, Tommy Reamon, played the role of Delma Huddle in the 1979 movie “North Dallas Forty.”

* Michael loves to fish. He first got into the sport when he was 10, casting his line into the waters of the James River.