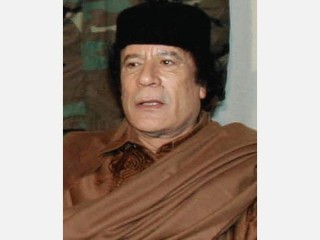

Muammar Al-Gaddafi biography

Date of birth : -

Date of death : -

Birthplace :

Nationality : Libyan

Category : Politics

Last modified : 2010-07-22

Credited as : Politician, Leader of Libya, World's political leader

0 votes so far

From 1972, when Gaddafi relinquished the title of prime minister, he has been accorded the honorifics "Guide of the First of September Great Revolution of the Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya" or "Brotherly Leader and Guide of the Revolution" in government statements and the official press.[2] With the death of Omar Bongo of Gabon on 8 June 2009, he became the fourth longest serving of all current national leaders. He is also the longest-serving ruler of Libya since Ali Pasha Al Karamanli, who ruled between 1754 and 1795.

Mu`ammar al-Qaddafi was born in the region of Sirte in early 1942 (the exact date of birth is unknown) into a nomadic, Bedouin peasant family. The youngest child of a family belonging to the Qadhdhadhifa, an Arabized Berber tribe, he received a traditional religious primary education, and from 1956 to 1961 he attended the Sebha preparatory school in Sidra. He was influenced by the dramatic, revolutionary changes taking place in neighboring Egypt under Gamal Abdul Nasser, whose fervent appeals to Arab unity and condemnation of Western influence inspired young Arabs. The charismatic, nationalist young Qaddafi excelled in school and was politically active. The Sebha preparatory school, regarded as the birthplace of the Libyan revolution, was where Qaddafi and a small group of friends formed a nucleus of militant revolutionary leaders who would eventually take power in 1969. Qaddafi, an early admirer of Nasser and an Islamic fundamentalist, was expelled from school in 1961 for his militant political activities and views.

In 1963 he decided to follow Nasser's example by entering the Military Academy in Benghazi, where he and a few of his fellow militants organized a secret corps of "Free Unionist Officers," whose explicit aim was the overthrow of the moribund, pro-Western monarchy. He also organized a popular committee to attract young nationalists committed to a revolution and to his vision of a Libya free of foreign domination. After graduating from the academy in 1965, he was sent to Britain for further training, returning a year later as a commissioned officer in the Signal Corps.

On 1 September 1969 Colonel Qaddafi and young officers from the Free Unionist movement staged a bloodless, unopposed coup d'état in Tripoli, the capital, overthrowing King Idris Senussi I and gaining complete control of the country within a few days. While the coup leaders initially remained anonymous, the Revolutionary Command Council (RCC), chaired by Qaddafi, assumed power and proclaimed the Libyan Arab Republic. A mild power struggle soon surfaced between Qaddafi and the young officers on one side and the older senior officers and civilians who had participated in the coup on the other. By January 1970 Qaddafi, whose faction received support from Egypt, had assumed complete control after eliminating his opponents.

The principal ideological thrust of the new regime was a combination of Pan-Arabism, religious reformism, and what came to be called "Islamic socialism." After coming to power, the Qaddafi regime sought not only to rid Libya of Western presence and influence but also to undermine Western, particularly American, interests in the region. British military installations in the country were expelled in March 1970, followed by the much larger American presence in June, and Western specialists and technicians were replaced by Arabs. The regime's early foreign policy sought to foster closer ties with Egypt and other Arab states. Qaddafi espoused Nasser's conception of Pan-Arabism, becoming a fervent advocate of the unity of all Arab states into one Arab nation. He also became an advocate of Pan-Islamism, the notion of a loose union of all Islamic countries and peoples. After Nasser died on 28 September 1970, Qaddafi tried to assume his mantle of the ideological, revolutionary leader of Arab nationalism and the leading proponent for Arab unity. The Federation of Arab Republics (Libya, Egypt, and Syria) was officially proclaimed on 1 January 1972, but the loose arrangement soon proved impossible to bring to fruition when the three countries failed to agree on the specific terms of a merger. For Qaddafi, federation was the first step toward the creation of his "Arab Nation," with Egypt as the key element in any possible unification. He urged Egyptian president Anwar Sadat, who was unenthusiastic about a merger with Qaddafi, to agree to further measures on unification, organizing a "holy march" of thirty-thousand Libyans to Cairo to demonstrate Libyan support. Qaddafi, who had an uncompromising attitude toward Israel, also became a strong supporter of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), often putting him at odds with other Arab states he criticized for the lack of total commitment to the Palestinian cause.

On the domestic front Qaddafi sought to restore national control over Libya's economy and resources as well as to implement his vision of direct, popular democracy based on an entirely new political order. In April 1971 an agreement was reached with foreign oil companies operating in Libya for higher oil prices. By December the process of nationalizing foreign oil companies and other foreign businesses began with the nationalization of the assets of British Petroleum.

Cultural Revolution

In April 1973 Qaddafi launched a "cultural revolution," outlining a blueprint for the transformation of Libyan society and politics. The new social and political order was based on the tenets of the Koran and the rejection of foreign ideologies. In May he presented his "Third International Theory," which he hoped would serve as an alternative to "capitalist materialism and communist atheism." When strains and splits developed within the RCC in early 1974, Qaddafi relinquished his administrative duties and posts on 5 April to concentrate on ideological and popular mobilization revolving around his Islamic socialism. After reemerging in late 1974, he engineered the political and administrative reforms that established the so-called people's congresses, which were to be responsible for local and regional administration. Legislative power, previously held by the RCC, was turned over to the General People's Congress, with Qaddafi serving as secretary-general. This new political order was in effect a horizontal reorganization of society, which in theory would lead to the eventual withering of the state. The people themselves would become the authority; they would become the instruments of government, and their participation would be ensured at all levels.

Qaddafi outlined his political philosophy undergirding the new political order in his Green Book, published in 1976. After changing the country's name to the "Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya," Qaddafi became the "leader, theoretician and symbol of the revolution" in 1978, while the people theoretically exercised all power. While in theory the power o f the people was to be exercised by the people's congresses established at various levels of society, participation in decision making and de facto power remained limited. Although Qaddafi has not faced any known serious challenges to his power, there has been some domestic opposition to his rule, and during the 1980s there were several reported attempts to overthrow him. Qaddafi has responded to domestic and external opposition through violence, and in February 1980 his revolutionary committees called for the "physical liquidation" of Libyan dissidents living abroad, after which "hit squads" were sent abroad to silence opponents of the regime. On 17 April 1984, for example, Libyan representatives in the Libyan People's Bureau in London fired shots at Libyan dissidents during a demonstration, killing a British policewoman.

Relations with the Soviet Union

Qaddafi's international prominence has been based more on his aggressive, anti-Western, and unconventional foreign policies than on his domestic experimentation. The young regime set out to accomplish the ambitious goal of transforming the political landscape of North Africa and the Middle East. Qaddafi, a leading exponent of Arab nationalism following Nasser's death, sought to create for Libya a major role in North African and Middle Eastern politics based on Soviet-supported Libyan military strength and oil wealth. Despite an initial coolness, by the mid 1970s Libya had developed closer ties with the Soviet Union at a time when Egypt was drifting closer to the West. Libyan-Soviet relations were based more on a coincidence of geopolitical and military interests than ideology or shared objectives. Despite the lack of any formal treaties, by 1978 Libya had become the first country outside of the Soviet bloc countries to receive the supersonic MIG-25 combat fighters, signing new arms agreements in 1980 totaling $8 billion. Relations with the Soviet Union remained somewhat distant, however, as a result of Qaddafi's mercurial temperament and unpredictability.

Qaddafi's views and policies, however, alienated most of his neighbors and other Arab states in the Middle East. He openly criticized other Arab leaders who opposed his Pan-Arabic initiatives for union and publicly offered aid for the overthrow of moderate, pro-Western leaders in Chad, Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and the Sudan. His relations with neighboring Egypt deteriorated after he boycotted the October 1974 Arab summit in Rabat, Morocco, which recognized the PLO, under Yassir Arafat, as the sole representative of Palestinians. He subsequently began actively to support splinter factions within the PLO, the so-called rejectionist front, which rejected the possibility of a negotiated settlement with Israel. Relations between Libya and Egypt worsened precipitously, leading to a brief shooting war along the border in 1977. A major break between the two countries occurred after Sadat concluded his separate peace with Israel in March 1979. Libya became the leader of the "rejectionist states," the Arab states that opposed any type of settlement of the Arab-Israeli conflict short of the destruction of Israel, and Qaddafi called for the total political and economic isolation of Egypt.

Throughout the 1970s Qaddafi's regime was implicated in subversive and terrorist activities in both Arabic and non-Arabic countries. As did other the Arab countries, Libya also became a major supplier of financial and military assistance to terrorist groups as well as revolutionary and secessionist movements throughout the world, including North Africa, Zaire, New Caledonia, Northern Ireland, and Nicaragua. Qaddafi also sought to increase Libyan influence in sub-Saharan Africa, especially in states with an Islamic population. He called for the creation of a Saharan Islamic state and gave military support to antigovernment forces in Mali, Sudan, Niger, and Chad. In 1973 Libyan forces invaded Chad and annexed the mineral-rich Aozou Strip, the territory along Libya's southern border. Qaddafi's armed involvement in Chad continued into the 1980s, increasing support to secessionist rebels in the civil war, including the introduction of Libyan troops, which enabled rebel forces to capture the capital city in December 1980. Soon after the Libyan-installed rebel leader and Qaddafi announced plans for a merger of the two countries, which brought international outcry and opposition, especially in West Africa. Under international pressure, Libya's estimated fifteen thousand troops were forced to withdraw back to the Aozou Strip. The forces of Hissein Habre ousted the rebel government in 1983, retaking the southern half of Chad and inflicting heavy losses on the Libyan-backed rebels. In response to a new Libyan-backed rebel offensive, France responded to a request by the Chad government by deploying three thousand troops in Chad. Despite a September 1984 Libyan-French agreement to withdraw foreign troops from Chad, Libya continued to keep nearly seven thousand troops in the northern region to assist rebel offensives. By March 1987 government forces had succeeded in driving back the rebels and forcing Libyan forces to withdraw toward the Aozou Strip, killing an estimated four thousand Libyan soldiers in three months of fighting. Following an 11 September 1987 cease-fire agreement, efforts were made by both sides and third parties to reach a settlement, and on 3 October 1988 the two countries announced the resumption of diplomatic ties, even though no progress had been made on the status of the Aozou.

In January 1980 a brief crisis erupted between Libya and Tunisia after an alleged Libyan-backed raid on a Tunisian mining town, prompting France to send military assistance to Tunisia in the event of a Libyan attack. Following the burning of the French embassy and consulate in Libya, Qaddafi vowed to counter France's interests and intervention in Africa by any means. In early 1980 a more serious rift developed between Libya and Arafat's al-Fatah, the largest faction in the PLO. After relations were formally broken with al-Fatah, Qaddafi openly supported the revolt against Arafat's leadership and increased Libyan political and material support for Palestinian splinter groups, many of whom were based in Libya. Libyan-Sudanese relations deteriorated over the Chadian invasion and Libya's involvement in antigovernment subversive activities. Libya was implicated in the 1988 overthrow of Jafar Mohammed Nimeiri in the Sudan. Qaddafi had also supported Ugandan leader Idi Amin, unsuccessfully airlifting Libyan troops to Amin's rescue during the 1979 civil war. In spite of his denunciations of moderate Arab leaders and support for subversive activities, he has frequently changed course in his relations with countries in the region. On 13 August 1984 Libya and Morocco unexpectedly announced a political union treaty, abrogated by Morocco's King Hassan in August 1986. In October 1987 Libya and Algeria agreed in principle to a political union, and in April 1988 Libya and Tunisia, with which Libya had formed a short-lived union in 1974, signed a cooperation pact. Qaddafi sees himself both as a leader of the Arab and Islamic world as well as the Third World and has attempted several times to become the chairman of the Organization of African Unity (OAU).

Qaddafi's militant foreign policy and active support for revolutionary movements and terrorist organizations, from various Palestinian terrorist groups to the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and the Japanese Red Army, have placed Libya in open conflict with the Western countries, principally the United States. Strained relations with the United States since 1969 gave way to mutual hostility following the sacking of the American embassy in Tripoli. In May 1980 Qaddafi, angered by the American arms embargo and export limitations, demanded billions of dollars in compensation from the United States, Britain, and Italy for the damages Libya sustained during Allied campaigns in World War II.

Libya became a principal t arget of the aggressive anti-terrorist policy and tough stance towards radical Third World states adopted by the new U.S. administration of Ronald Reagan, which took economic and political measures to isolate Libya and to try to bring about the downfall of Qaddafi. Tense relations flared into armed conflict in 1981 when two American jet fighters shot down two approaching Libyan fighters during American naval maneuvers in the Gulf of Sidra. The United States accused Libya of promoting international terrorism and producing chemical and biological weapons. Relations between Libya and the United States, which also accused Libya of seeking to acquire nuclear weapons, degenerated to their lowest point toward the end of 1985, following terrorist bombings in the Rome and Vienna airports by the Abu Nidal terrorist group based in Libya. A dispute over navigational rights in the Gulf of Sidra, all of which Libya claimed constituted its territorial waters, led to another armed clash on 24--25 March 1986 when American fighter aircraft bombed missile and radar installations in the coastal town of Sirte after Libya had fired ground-to-air missiles at American aircraft flying inside the gulf. The Reagan administration, which accused Libya of sponsoring the 5 April terrorist bombing of a West Berlin discotheque, which killed an American soldier, ordered air raids against military installations, airports, suspected terrorist training camps, and government buildings, including Qaddafi's residential compound, in Tripoli and Benghazi. Although the administration had hoped the raids would lead to his ouster, Qaddafi managed to turn the American attack to his advantage domestically and internationally. Another clash came in January 1989, when two Libyan fighter aircraft were shot down by American fighters in international waters amid new tensions produced by American accusations that Libya was producing chemical and biological weapons with West German and Japanese assistance.

Qaddafi continued making headlines throughout the late 1990s for various, sometimes surprising, reasons. In 1995, he began expelling Palestinians from Libya, many of whom were families who had been in the country for decades. "It was his way, he said, of protesting the Palestine Liberation Organization's peace treaty with Israel," reported Alan Sipress for the Knight-Ridder/Tribune News Service. Then in October of 1996, South African President Nelson Mandela, a living symbol for human rights activists, called Qaddafi "my dear brother leader" and presented him with South Africa's highest award for foreigners, the Order of Good Hope. Libya had supported Mandela's outlawed African National Congress, which sought to end apartheid in South Africa, landing Mandela in prison for 27 years. In early January of 1997, President Clinton extended sanctions on Libya for executing eight spies allegedly linked to the United States because they used CIA-provided equipment. Also that month, Qaddafi caused trouble for American millionaire Steve Fossett, who was attempting to fly a hot-air balloon around the world. When Libyan officials denied him permission to cross over the country, Fossett made plans to circumvent the region. A year later, during Fossett's journey, Qaddafi personally reversed the decision, but the balloon pilot was already on a new course.

In 1997, Qaddafi accused French and British secret service personnel, as well as members of the British royal family, of being responsible for a conspiracy which killed Princess Diana and her companion, Dodi al-Fayed, in a car crash in France on August 31, 1997.

Also in 1997, Qaddafi maintained his reputation as a thorn in the side of the United States when he demanded that America extradite the persons responsible for the previous decades' air raids on Libya before he would consider extraditing the suspects in the Lockerbie plane bombing. In March 1998, the World Court in the Hague, Netherlands, decided that it would be the ruling body in the case of the bombing suspects instead of ordering them to be extradited to the United States or Britain. Enforcement of the ruling, however, was dependent on the United Nations Security Council. In February 2001, only one of the two Libyan intelligence officers accused of the crime was convicted; the other officer was set free and returned to Libya. Soon after the completion of the trial Qaddafi announced plans to reveal evidence which he believed would prove the innocence of the Libyan intelligence officer convicted of the bombing.

Immediately following the September 2001 terrorist attacks in the United States, Qaddafi dispatched his highest security official to the U.S. to share sensitive intelligence with Washington. Libya was already at odds with the allegedly responsible terrorist organization and had been for a number of years. In March 1998, for example, Libya became the first country to issue an Interpol arrest warrant for bin Laden, the warrant coming five months before attacks on the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania. The inter-Arab dispute was over Libya's secular government, which had made it one of al-Qaeda's earliest enemies. A year later, Libya retracted its offer of assistance.

In another curious move, Qaddafi, in December 2003, exposed his own banned-weapons program and invited U.N. inspectors to take away his stash of weapons of mass destruction. It turned out that Qaddafi had a nuclear and chemical weapons program more fully developed than anyone realized. According to The American Enterprise,, Britain's Daily Telegraph reported that Qaddafi had telephoned the Italian prime minister several months after the United States invaded Iraq and said, "I will do whatever the Americans want, because I saw what happened in Iraq, and I was afraid." President George W. Bush hailed Qaddafi's turnabout and used it as justification for the war in Iraq, suggesting that other rogue nations, like North Korea, Iran, and Syria, might follow suit because they, too, feared the United States' military might.

Many political analysts insist Qaddafi's about-face had nothing to do with Iraq, but was motivated by a need for money. For years, Libya had been bogged down by crippling sanctions from the U.N., the United States, and Britain. The sanctions isolated the country and basically tied the hands of its oil companies. Political insiders believe Qaddafi wanted the sanctions lifted and that is why he came forward with his weapons program. "It was a calculated bid by Qaddafi to keep power," contends Claudia Rosett of the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies. "U.S. recognition, let alone praise, brings with it enhanced status, authority, and an implication that sanctions may be lifted, oil deals may flow, Qaddafi's coffers may be refilled, and his reign of repression may carry on unrebuked," she told The American Enterprise. That is exactly what happened. In April 2004, Bush awarded Qaddafi generously for his deed by relaxing sanctions and removing a 23-year travel ban to the country. Bush also talked about normalizing diplomatic relations.

Not everyone remains convinced that Qaddafi is a changed man. Frank Gaffney, president of the Center for Security Policy, believes Qaddafi still has banned weapons. Gaffney noted that Qaddafi's "Man-Made River" project could be used to conceal and move weapons. The river is a man-made network of underground tunnels built across the country to move water.

Human rights groups were upset by Bush's attempt to normalize relations with Libya, given its human-rights violations. As one analyst told Newsweek, "I haven't seen the U.S. emphasize that they want to see progress on human rights . . . They're not making it the centerpiece of their discussions. The most important thing for Bush in Libya is that" Qaddafi "gave up WMD. I guess human rights were the price."

After Bush lifted sanctions, U.S. oilmen flocked to Libya to wheel and deal. Many were Bush campaign donors. It is estimated that Libya has 36 billion barrels of oil reserves, valued at $1 trillion. Within days of the lifted sanctions, Libya's National Oil Corporation announced its first oil sale to a U.S. company in nearly 20 years. Following suit, several European leaders also traveled to Libya, including Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi and British Prime Minister Tony Blair. Qaddafi himself traveled to Brussels, Belgium, in April 2004. It was the first time he left Africa or the Arab world in 15 years.

In another turn of events, Qaddafi's daughter, Aicha, a law professor, joined the Jordanian-based multinational defense team of deposed Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein in July 2004. In a statement, she said she wanted to be sure he received a fair trial and was considered innocent until proven guilty.

Always yearning for the spotlight, Qaddafi took credit for Bush's 2004 re-election during an interview with Italian television in December 2004. Qaddafi said that he was still waiting for the U.S. to reward him for giving up his weapons program. He also claimed Libya was a partner with the United States in the war on terror and he hoped other countries would accept Libya as "a model of moderate Islam." However, according to Libyan dissidents, Qaddafi's government was still funneling money to militants operating out of Saudi Arabia. As for the future, Gaffney, speaking to The American Enterprise, urged nations to tread cautiously in dealing with Qaddafi. "There is powerful reason, given his track record, to be concerned that this dictator will not honor his commitments. Qaddafi is notoriously erratic, unpredictable and unreliable."

Despite Qaddafi's unpredictability, the United States began moving cautiously toward normalizing relations with Libya. In August 2005 U.S. Sen. Richard Lugar visited Libya, becoming the highest-ranking U.S. official to set foot in the county in decades. The visit was made in an effort to rebuild ties between the nations. After Lugar's departure, the U.S. Department of State began negotiating the possibility of opening an embassy in Libya. At a press briefing, according to BBC News, U.S. Department of State spokesman Sean McCormack told reporters that while relations have improved, there was still more work--on Qaddafi's part--to be done. "We are engaged with them on a variety of issues. You mentioned human rights, you mentioned democracy, you mentioned issues of terrorism," he told reporters. "If they continue to make progress along the pathway that we have laid out, we, again, will meet their acts of good faith in return." If the United States opens an embassy in Libya, it would be a huge step for Qadaffi in proving to the world that he wants to achieve peace with the West.

Relations continued to move towards normalization in 2006. In May of that year, the Bush administration decided to remove Libya from the U.S. list of state sponsors of terrorism as well as resume full diplomatic relations with the country. Several reasons were cited for the policy changes towards Libya including an admission of responsibility for the 1988 bombing of Pan Am flight 103, an agreement to cease nuclear and chemical weapons development, and stopping all terrorist activities. The changes in relationship with Libya, and all the benefits therein, were also to serve as a positive example to other difficult countries like North Korea and Iran. In an interview with Arabic television channel Al-Hurra, Qadaffi was pleased with the change. He was quoted by the UPI International Intelligence Wire as saying, "I think all efforts are heading towards ending animosity."

June 14, 2007: Qadhafi and Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe called for Africa to unite and for the African Union to be turned into a federal government for Africa, similar to the European Union in Europe.

August 30, 2008: Qadhafi signed a "friendship pact" with Italian prime minister Silvio Berlusconi. The pact committed Italy to paying $5 billion to Libya, which was an Italian colony between 1911 and 1943, as reparations for wrongs committed by Italy during colonial rule.

September 1, 2008: Qadhafi announced that the Libyan government would soon begin distributing the country's oil profits directly to the people, instead of adding that money to the government's budget.

October 31, 2008 - November 2, 2008: Qaddafi visited Russia for the first time since 1985. While there, he discussed oil and gas issues with Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin and President Dmitry Medvedev.

August 21, 2009: Qaddafi expressed thanks to British Prime Minister Gordon Brown and Queen Elizabeth II for the release of Abdel Basset al-Megrahi from a Scottish jail; Megrahi, who has terminal prostate cancer, had been serving a life sentence for participating in the 1988 bombing of Pan Am Flight 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland.

February 25, 2010: Qaddafi exhorted Muslims around the world to support a jihad against Switzerland.