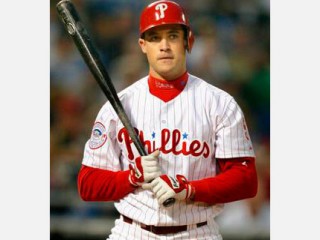

Pat Burrell biography

Date of birth : 1976-10-10

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Eureka Springs, Arkansas

Nationality : American

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2010-10-16

Credited as : Baseball player MLB, Leftfield with the Philadelphia Phillies ,

0 votes so far

Pat not only played football, basketball and baseball as a kid, he and friends were such fanatical athletes that they made up their own sports. They mastered the art of flicking bottle caps and pennies, creating a number of different games around this sublime skill. They delighted in nailing stop signs from moving cars with coins, and learned to produce hellacious curves and change-ups in their bottle-cap baseball contests. Anyone wondering how Pat learned to handle off-speed stuff need only imagine the countless cuts he took at these dipping, darting metal spheres. Wiffle ball only enhanced this skill. The Burrell's backyard, site of year-round games, was surrounded by an ivy-covered fence, and was referred to by friends and family as "Wrigley."

Pat’s idol was George Brett, the All-Star third baseman for the Kansas City Royals. He marveled at the lefty's compact, no-frills swing, his ability to lash the ball with power to all fields, and the way he busted it down the first base line, even on routine groundballs. Whenever the Royals embarked on a West Coast swing, Pat begged his father to take him up to Oakland to see his hero. John gladly fed his son's interest in baseball. When Pat came home from baseball practice in the spring and summer, he called his father outside to play catch. John never turned down a request from his boy.

In 1991, Pat entered San Lorenzo Valley High School in Boulder Creek. He spent the fall calling signals as the quarterback on the freshman football team, then joined the freshman basketball team. But he made his biggest splash for the Cougars the following spring on the diamond. An infielder and pitcher, the frosh began building his reputation as an emerging star. He was tall and powerful, and could hit the ball a mile.

That summer Pat considered his options. San Lorenzo was a good school, but he didn't feel it had a high enough profile. Dreaming of one day playing in the big leagues, he transferred to Bellarmine College Prep before his sophomore season. An all-boys Jesuit high school in San Jose, Bellarmine was a member of the competitive West Coast Athletic League, which would give Pat the visibility he needed to be discovered by pro scouts and major college coaches.

Bellarmine was a good 30 miles from Boulder Creek, a commute that ate up more than an hour a day for Pat. A gifted student, he admits what little time he had for a social life was wasted at a school with no female students.

Beginning in the fall of 1992, Pat became increasingly focused on baseball. Envious of wealthier teammates who had batting cages installed in their backyards, he compensated by eating, drinking and sleeping hardball. While he continued to play other sports—he was Bellarmine's varsity starter at quarterback as a junior and also handled the punting and placekicking duties—he did so with diminishing interest. Prior to his senior year, Pat decided to give up both football and basketball.

By this time, Pat—who stood well over six feet and weighed more than 200 pounds—knew he had an excellent shot at either receiving a scholarship to a big-time college baseball program or jumping straight to the pros. As a junior for the Bells he had batted .374. His mammoth drives regularly sailed over Bellarmine's left-center field fence, scattering the shot-putters training beyond it. Pat also amazed his teammates with his appetite for hard work. No one put as much effort into improving his game.

Bellarmine baseball coach Gary Cunningham realized he had a once-in-a-lifetime talent. Even in the WCAL, which annually produces major college prospects, Pat was feared. Teams pitched around him so often that Cunningham used the unorthodox strategy of hitting his slugger in the lead-off spot. The move forced opponents to throw to Pat at least once a game. In his senior year, despite seeing a limited number of hittable pitches, he batted .369 with 11 home runs and 29 RBIs.

Voted the California Coaches 1995 Player of the Year, Pat was the grand prize in a cross-country recruiting contest. The last two schools standing were Miami and Cal State Fullerton, both of which boasted proud baseball traditions. The Boston Red Sox also entered the fray, taking Pat with the 43rd pick of the draft. But when the Bosox refused to include a signing bonus in their contract offer, he settled on the Hurricanes.

That summer Pat was hand-picked to fill one of 15 roster spots on a Connie Mack traveling all-star team based in Enon, Ohio. To this day, he calls the experience one of the most important of his life. Coached by Ron Flusher, an associate scout for the Cincinnati Reds, the squad toured the country over a three-month period, compiling a record of 80-7. In 200 at-bats, Pat hit .400 and belted 20 home runs. He also got important time at third base, the position he was likely to play in college.

The schedule was grueling. The team played double-headers every day except Thursdays and Sundays. Back in Enon—a sleepy town 15 miles outside of Dayton that didn't even have its own grocery store—Pat lived with 13 teammates in a house that had two bathrooms and one shower. On days off, they were expected to wait on patrons at the local bingo hall, where money was raised to cover the team's expenses.

Pat learned a lot about himself during the summer. He also emerged a more polished player. Flusher helped him gain greater patience at the plate, which made him an even deadlier hitter.

ON THE RISE

Despite his summer baseball tutorial, Pat had modest expectations going into his first college season at Miami. The team’s best hitter, senior Rudy Gomez, was a fixture at third base, and slugger T.R. Marcinczyk was slated to play first. The only hole in the infield was at second, which was not an option for Pat. It did, however, create an interesting option for coach Jim Morris. Looking for a way to get Pat playing time, Morris asked Gomez to try his hand at second. The experiment was a success, and along with shortstop Alex Cora—a future major leaguer—the Hurricanes had one of the nation’s best infields when the season started.

Pat homered in his first college game and swatted five long balls in his first six contests. The freshman continued to swing a scorching bat all year long, partly because of a strict practice routine that included 200 cuts a day and long sessions in the weight room three times a week. Before games he spent at least an hour in the batting cage. The work paid off. Pat finished the campaign as the nation's leader in batting (.484) and slugging (.948). In 64 games, he blasted 23 homers and collected 64 RBIs. Miami went 50-14 behind the hitting of Pat and Gomez (.420), the pitching of Clint Weibel and J.D. Arteaga (27-4 combined) and the relief work of freshman Robbie Morrison (14 saves).

Pat was even more dominant in the post-season. He hit a staggering .772 in the NCAA Regionals and .500 in the College World Series. The Hurricanes cruised through the CWS to a championship showdown with LSU. Miami opened a 7-3 lead, but the Tigers got to Arteaga and Morrison to tie the score at 7-7 after eight innings. In the top of the ninth, the ’Canes rallied for a run, and sent Morrison out to seal the deal against the tail end of the LSU order. DH Brad Wilson doubled to open the inning and advanced to third, but Morrison retired the next two hitters. That left Warren Morris, a walk-on who scrapped his way into the Tigers’ starting lineup, as the only man standing between Miami and victory. Morrison started Morris out with a curve, and the diminutive second basemen caught it just right. He pulled the ball just over the rightfield fence for his first homer of the year—and arguably the most dramatic dinger in the history of amateur baseball—and a 9-8 LSU victory. Pat and his teammates were stunned as Morris rounded the bases.

It was little consolation when Pat learned he had been named the tournament's Most Outstanding Player. He joined Minnesota’s Dave Winfield (1973) and Cal-State Fullerton’s Phil Nevin (1992) as the only players to claim the award even though their teams did not win the CWS.

The following summer Pat traveled to Massachusetts to play for the Hyannis Mets of the Cape Cod League. Surrounded by the country's top amateur talent, he concentrated on his defense at third. After leading the Hurricanes in errors his freshman season, he knew his glovework was sub-par.

Pat returned to Miami under the weight of huge expectations. Baseball America ranked him as the third-best college prospect in the nation, and fans wondered how he would follow up his sensational freshman campaign. He did not disappoint, topping the .400 mark again, with 21 homers and 76 RBIs in 69 games. The Hurricanes had a great team, with future major leaguers Jason Michaels, Bobby Hill and Aubrey Huff joining Pat in the lineup. Arteaga and Morrison pitched well, and Miami finished with 51 wins—one better than the year before. The team breezed through the post-season, but ran into trouble during the College World Series, losing to red-hot Alabama in the semis, 8-2—denying the team a chance for revenge against LSU, which won the national championship again, this time behind slugger Brandon Larson.

The most difficult part of the season for Pat was adjusting to the way he was being pitched. Strikes were few and far between, which forced him to become more selective at the plate. Thanks to his quick wrists, however, Pat had an extra instant for pitch recognition. As he began to think along with the pitchers, he also became a very good situational hitter.

While Pat quietly enjoyed another superb campaign, it was another hitter who grabbed the headlines in Florida. J.D. Drew of FSU had a monster year for the Seminoles. When the end-of-season honorees were announced, Drew won the Golden Spikes Award and Pat was named First-Team All-America at DH, with UCLA’s Troy Glaus copping honors at third base.

That summer Pat joined the U.S. National team. Coached by Cal's Bob Milano, the squad boasted a "Who's Who" of college baseball. Among Pat's teammates were future pros Eric Munson, Adam Everett, Jason Tyner and Jason Jennings. The Americans toured the globe, posting a record of 21-13 against the likes of Japan, China and Cuba. In their stiffest test, they advanced to the semifinals of the Intercontinental Cup in Spain, but lost to Australia and fell out of medal contention. Pat hit third in Milano's lineup, though he often had the bat taken out of hands by opposing managers. Drawing 44 walks in 33 games, he batted .343 and led the team in home runs (12) and RBIs (42). For his efforts he was named Summer Player of the Year by Baseball America.

Heading into his junior year at Miami, Pat had grown accustomed to the intense media attention focused on him. A First-Team All-American in each of his first two seasons, he had also twice been a finalist for the Golden Spikes Award. No one doubted he would be a high pick in the 1998 draft. Until then Pat looked forward to another exciting season with the Hurricanes. He and Jason Michaels were now the most imposing 1-2 punch in college baseball.

The first half of Pat's junior year went as expected. More and more, with teams afraid to pitch him on the inside half of the plate, he was driving the ball the opposite way. Going into March, he was hitting .433 with 11 homers. But toward the end of the month Pat was grounded by stress tension to a vertebra in his lower back. While the injury probably wouldn't become a chronic problem, it did require time to heal, and he missed two months of play. By late May, with the NCAA Regionals fast approaching, Pat was racing the clock to get back into the lineup.

Pat returned for a game against Bowling Green, and in his first at-bat homered to deep left. From there he reassumed his role as the driving force in Miami's charge for the national championship. At 50-10 the Hurricanes were among the favorites to go all the way. Though they suffered an upset loss to North Carolina in their bracket of the regions, they survived thanks to Pat, who slammed five home runs in five games. But Miami's title hopes were dashed a short time later. The Hurricanes won just one of three games in the College World Series, and were eliminated by Long Beach State.

During the CWS Pat learned he had been selected with the top overall pick by the Phillies. The news was met with cautious optimism by fans in Philadelphia—the previous summer the club had taken J.D. Drew with the top pick, only to see him rebuff the franchise when it didn't meet his exorbitant contract demands. To their relief, Pat inked a five-year deal that included a $3.15 million signing bonus.

With rising star Scott Rolen at third, the Phillies switched Pat to first base. The thought of having two young sluggers anchoring the infield had executives throughout the Philadelphia organization dreaming of a string of World Series titles.

Pat began his career in Class A with the Clearwater Phillies in the Florida State League, where he joined fellow prospects Jimmy Rollins and Brandon Duckworth on a team that finished a game out of first place. The club's manager, Bill Dancy, liked Pat immediately. He had little trouble making the adjustment from aluminum to wooden bats, going seven for his first 19, and worked hard to master the footwork required by his new position. Though Pat struggled through some rough weeks, he finished strong, hitting .303 with seven homers and 30 RBIs in 37 games. He was named one of the FSL’s top prospects—not bad for a circuit that boasted fast-track talent like Nick Johnson, Billy Koch, Alex Sanchez, Jae Weong Seo, Adam Eaton and Tony Armas, Jr.

Despite Pat’s strong showing, the Phillies were in no rush to hurry his development. The club already had a solid first baseman in Rico Brogna, an excellent gloveman who had topped the century mark in RBIs during the 1998 season. Knowing he was likely to start the year in the minors, Pat worked in the off-season on his one glaring deficiency at the plate—his susceptibility to hard stuff on the hands. He also hunkered down for training sessions with Phillies rehab trainer Hap Hudson, and sought the advice of the strength and fitness experts at the Nick Bollettieri Tennis Academy in Bradenton, Florida.

Come the spring, Pat was handed over to coaches John Vukovich and Chuck Cottier, Philadelphia's resident fielding gurus. Although the kid would never be a Nureyev at first, both were impressed by Pat's ability to take instruction and his desire to improve at first base. So was Gary Varsho, Pat’s manager at Class AA Reading. Pat opened the season on fire, but what really caught Varsho's attention were the 22-year-old’s long sessions in the batting cage.

Pat missed 12 games in May with a nasty knee laceration, then picked up the pace when he returned to the lineup. That June, he batted .353 with six homers and 20 RBIs. Pat continued to sizzle in July and was named the Eastern League's player of the month. He also appeared in the Double-A All-Star Game in Mobile, Alabama.

At the end of August, the Phillies promoted Pat to the Class-AAA Scranton/Wilkes-Barre Red Barons, just in time for the playoffs. In five post-season games, he hit .522 with three HRs and eight RBIs. By then he was also taking in a new view on defense. The Philly front office, still concerned about his clumsy play at first, moved him to the outfield. To their relief, the 22-year-old never blinked. Under the tutelage of Varsho and Reading coach Milt Thompson, he picked up the nuances of leftfield right away, developing adequate footwork, gaining a feel for correct positioning and increasing the distance and accuracy of his throws.

At season's end, Pat led all Phillies minor leaguers in batting (.320), total bases (271) and home runs (29). Among the honors he collected were the Eastern League Rookie of the Year, the Paul Owens Award as the Phillies’ top minor league player, and the Eugene L. Shirk Award for Community Service (which he shared with pitcher Thomas Jacquez).

Eager to hone his game further, Pat gladly played for the Peoria Javelinas in the Arizona Fall League, where he finished with a .330 batting average and tied for second in the league in extra-base hits (18). The sum of his breakout season gave Phillies GM Ed Wade a lot to think about. Philadelphia's perennial weakness was starting pitching, and the free agent market was rich in hurlers. The Phillies also owned some interesting trade bait. Indeed, with Pat on the fast track to the majors, Brogna and outfielder Ron Gant—both coming off good years—became expendable.

MAKING HIS MARK

The Phillies mulled over their options in spring training of 2000. Pat didn't make their decision an easy one. During the exhibition schedule he hit .286 with three homers, and showed all the signs of being major-league-ready. Gant and Brogna did nothing in March to lose their jobs, however, so Pat was assigned to Scranton to begin the year.

His stay in the minors didn’t last long. Brogna broke a bone in his left hand in early May and underwent surgery soon after. Two weeks later, Pat was summoned from Scranton to join the team for a series against the Astros in Houston. In the lineup that night, he collected two hits, including a run-scoring triple in the ninth off the center field wall to key a 9-7 comeback victory.

Though he had played exclusively in leftfield for Scranton, Pat was inserted at first base for the Phillies. While he had his ups and downs during his rookie campaign, he always seemed to be in the middle of the action. In a June series in New York, he homered off Armando Benitez in the ninth—his second dinger of the game—for a 3-2 win. Pat victimized the Mets closer again the following night, blasting his first big-league grand slam for another dramatic victory.

In August—after a trade that brought Travis Lee, Omar Daal and Vicente Padilla over from Arizona for Curt Schilling—the Phillies moved Pat back to left, a switch they said was final. Meanwhile, he was garnering support as the NL Rookie of the Year. His numbers at season's end were impressive, including 27 doubles, 18 home runs and 79 RBIs. But Atlanta shortstop Rafael Furcal wound up taking the award as the league's top newcomer.

Pat entered spring training of 2001 with a clearly defined role on the Phillies. New manager Larry Bowa penciled him in as his starting leftfielder and number-six hitter. With Lee, Rolen and catcher Mike Lieberthal joining the young slugger, the club boasted plenty of muscle in the heart of its order. If speedsters Jimmy Rollins, Doug Glanville and Bobby Abreu could set the table for them, the Phillies had the potential to be a scary offensive club.

Bowa's big questions were in the pitching department. Daal and Padilla were fighting for spots in the rotation with a group that included Bruce Chen, Robert Person, Randy Wolf and Dave Coggin. The bullpen was led by recycled closer Jose Mesa.

With Bowa cracking the whip from Day One, the Phillies exceeded all expectations. Person enjoyed the best year of his career, anchoring the pitching staff with 15 wins. Mesa surprised by saving 42 games and logging a 2.34 ERA. Philadelphia battled the Braves for first in the NL East all season long, but fell short of a playoff berth by two games. Still, with his team finishing at 86-76, Bowa was an easy choice as his league's Manager of the Year.

On offense, the Phillies ran opponents ragged. The team's 153 stolen bases topped the NL, and Rollins led the league with 12 triples. Abreu, meanwhile, became the first outfielder in franchise history to log a 30-30 season.

The Phillies, however, often struggled to score runs. Pat was part of the problem at times. With a more thorough scouting report on him circulating among NL clubs, he had trouble adjusting to the new pitching patterns he was seeing. He was inconsistent most of the year, and Bowa angered him by benching him a couple of times. It wasn't until the All-Star break that Pat finally began to find his comfort zone at the plate. While he was still swinging through too many deliveries, his numbers in the second half rose, and he showed that he could handle the heat of a pennant race. Pat ended the year at .258 with 27 home runs (18 of which came after June) and 89 RBIs. He also struck out 162 times.

In the off-season Pat sat down with Bowa to discuss the coming campaign. The manager asked his leftfielder to write down his goals for 2002, then keep them hidden until the end of the year. He wanted Pat to have a clear idea of what he hoped to accomplish, but not obsess over his stats.

Bowa also hoped to get a read on Rolen. In the last year of his contract, he was hinting that he wouldn't return to Philly, which put the team in a difficult position. If the Phillies weren't an obvious playoff contender by July, Wade had to consider moving his third baseman, rather than losing him to free agency for nothing.

There was no guarantee that Philadelphia would mature into a consistent club. Again, several pitchers had to prove themselves, and the young lineup was being counted on to continue its development. Clouding both these pictures was the status of Lieberthal, who was coming off a knee injury.

Unfortunately for the Philly faithful, the team was unable to reproduce the magic of its 2001 campaign. The Phillies went 80-81, stumbling home more than 20 games behind the front-running Braves That's not to say there weren't any highlights. Padilla earned a spot on the All-Star team and finished with 14 wins, Wolf was lights-out in the second half, and young guns Brandon Duckworth and Brett Myers picked up valuable experience on the hill.

The offense was disappointing, starting with Rollins and Glanville, both of whom failed to reach base consistently. Lieberthal was also slow in his recovery, which further weakened the lineup. As the trade deadline neared, Wade pulled the trigger on a deal that sent Rolen to St. Louis for spare parts, essentially ending Philadelphia’s season.

As for Pat, he provided the only hitting highlights for Philly, as he set career highs in every batting significant category. His 37 home runs and 116 RBIs were the most by a Phillie since Mike Schmidt in 1986, and ranked seventh and third in the NL, respectively.

Pat started the year on a tear, launching a pair of game-winning, walk-off homers in early April against division rivals Florida and Atlanta. Several weeks later he reached rarified air by blasting one into the upper deck of the leftfield seats at Veterans Stadium. In June, Pat embarked on a season-high 11-game hitting streak, and by the All-Star break he had 22 home runs. In August, he recorded the third multi-homer game of his career, going deep twice against the Expos, including a grand slam off Matt Herges. After the season he was invited to join the Major League All-Star team that toured Japan.

With his breakout 2002 campaign, Pat lived up to his immense potential and established a level of performance that boosted him to superstar status. The pressure on Pat mounted even more when he signed a six-year, $50 million deal to remain with the Phillies.

Convinced they had the talent to contend for a championship, the club made a major push to win. Jim Thome was signed to a huge contract, and free agent third baseman David Bell was brought in, too. Top prospect Marlon Byrd replaced Glanville in center, and Abreu beefed up to give the team even more power from the left side of the plate. The club also added a new staff ace in former Brave Kevin Millwood.

Pat did what so many young sluggers do after their first big contract—he tried to earn it all with every swing. Opposing hurlers figured this out early, and kept expanding the strike zone until Pat was swinging at anything remotely close to the plate. The Phillies remained patient, mostly because the rest of the club was coming together and playing good ball. Incredibly, Pat’s slump lasted all year. The longer it went, the more he pressed. When he got a fat pitch, he still nailed it, but most of the time Pat got himself out swinging at pitches out of the strike zone. He finished 2003 with an embarrassing .209 batting average, 21 homers and 64 RBIs.

The Braves, meanwhile, had a phenomenal season, which meant Pat and his teammates were playing for the Wild Card. The Phillies looked like shoe-ins until the Florida Marlins swept a late-September series and eliminated them from the race. Every finger in Philadelphia was pointing at Pat, and deservedly so. Although other Phillies played below anticipated levels, none fell as far short of expectations as their young leftfielder.

For their part, the Phillies were mystified. Pat worked with Mike Schmidt all year on his hitting and there was no improvement. The team resisted sending him to Triple-A and did not tamper with his mechanics during the season. But adjustments were called for over the winter.

Pat opened the 2004 season eager to prove that the '03 campaign had been a fluke. The Phillies were installed as favorites in the NL East, and part of their success would depend on their young slugger’s ability to rebound and have a good year. The picthing staff was also somehwat of an uncertainty. Bill Wagner was acquired in a trade with the Astros to solidify the bullpen, while the rotation was bolstered by the addition of lefty Eric Milton.

Pat started the year on a tear, hitting .328 with nine homers and 36 RBIs through Philly’s first 38 games. As Philadelphia approached the All-Star break, his numbers slowly came back to earth. Still, at .276 with 15 HRs and 62 driven home, he was far ahead of his 2003 pace.

With a record of 46-41, the Phillies clawed their way to first place in the NL East, but Atlanta, Florida, and New York all lurked within two games. Hoping to distance themselves from the pack, they began the second half with eight games against all three division rivals. The Phillies went .500 over the stretch, and Pat batted a disappointing .138. The team missed a golden opportunity to widen its lead, and it cost them. In July, the Braves got hot, and took control of the division race. Philly never recoeverd, ending the season out of the playoffs at 86-76, 10 games behind Atlanta.

Underachievers once again, the Phillies looked for a scapegoat. GM Ed Wade pointed the finger at Bowa, and promptly fired him.

Pat was one of several players who didn't help his manager's cause. A wrist injury slowed him, forcing him to miss more than 40 games. Pat opted not to have surgery during the season, knowing an operation would shelve him until 2005. He returned to the action in September, but didn't have much of an impact. His final numbers—.257, 24 homers, 84 RBIs and a .365 OBP—were respectable, though hardly befitting his nickname.

The Phillies entered the spring of '05 looking and feeling like a different team. In as manager was Charlie Manuel, a longtime favorite of Thome's for his laid-back style. Wade also added veterans Jon Leiber and Kenny Lofton to provide on-field leadership. The moves paid off initially, as Philly moved into playoff contention. The team stayed there despite an awful season from Thome, who was slowed by a painful right elbow and finally had surgery in July.

The Phillies rallied without their slugger. Rookie Ryan Howard provided the power missing without Thome in the lineup, and Rollins hit in 36 games in a row to finish the campaign. Unfortunately, it wasn't enough, as Philadelphia was edged by the Astros for the Wild Card.

Pat did everything he could to get his club into the post-season. With Abreu slumping down the stretch, Pat faced even more pressure as a run producer. But he had obviously learned from past failures. More patient and selective all year long, Pat worked opposing pitchers into counts where he could look for offerings he could handle. The results spoke for themselves. He raised his average to .281, his on-base percentage to .389 and his slugging average to .504. Pat topped the 30-homer mark for the first time since 2002, and set a personal high with 117 RBIs.

Pat started 2006 like a house afire, and finished with solid numbers—though not quite what he had attained in '05. He batted .258 with 29 homers and drove in 95 runs. Nearly a third of those RBIs were of the go-ahead variety. The Phillies, meanwhile, traded Jim Thome to open up a spot for Ryan Howard, and he responded with an MVP season. With Pat, Chase Utley and Jimmy Rollins, the offensive was amazing.

Pitching was the problem. The Phillies simply could not shut down other teams. Their 85 wins left them 12 games behind the Mets, and three games short of a Wild Card berth.

The 2007 campaign looked like a repeat. The Mets built a big lead and the Phillies lagged behind. New York fans delighted in this scenario, especially after Rollins had proclaimed Philadelphia the "team to beat" in spring training.

Pat, who got off to a horrid start, heated up in July and August, and the Phillies crept back into the NL East race. In the final two weeks, Philadelphia couldn’t lose and the Mets couldn’t win. The Philscharged into first place and won the division crown on the final day. A rag-tag rotation pitched well, with Jamie Moyer, Kyle Kendrick, Adam Eaton and young Cole Hamels all winning in double figures. Brett Myers handled most of the closing duties.

Pat’s final stats were similar to '06—.252, 30 homers, 97 RBIs. But his performance over the second half had teammates raving. Four of his homers came in a pivotal four-game sweep of the Mets in late August. He also boosted his on-base percentage to .400 for the first time, thanks to a career-high 114 walks. Pat heard plenty of boos in May and June, when he slumped badly, but his heroic summer surge won back the Philly fans and played a huge part in his team’s historic comeback.

In the NLDS—Pat’s first as a major-leaguer—the Colorado Rockies pounded Philadelphia pitching at Citizen’s Bank Park to take the first two games. Pat homered in Game 1, but it made little difference. In Colorado, the Phillies dropped a 2–1 pitching duel, ending their amazing season prematurely.

The Phillies plugged a major hole in 2008 when they signed Brad Lidge to be their closer. He was lights-out all year, enabling the team to keep the NL East race close. The season turned on August 26, when the Phillies erased a seven-run deficit against the Mets to win in 13 innings. The victory boosted them into first place and set the tone for September. A four-game sweep of the Brewers late in the campaign set them on a winning track, and they won the NL East for the second year in a row.

As had become customary for Pat, his year was a tale of two seasons. Red hot in the first half, he struggled to find his timing after the All-Star Break. Pat finished the season with a mediocre .250 average but made his 134 hits count. He had 33 homersand 33 doubles to boost his slugging average over .500. He drew 102 walks and drove in 86 runs.

Against the Brewers in the NLDS, the Phillies took the first two games, dropped the third, and then won Game 4 by a score of 6–2. Pat socked two home runs in the game and knocked in four runners.

The Phillies kept rolling against the Dodgers in the championship series. Pat won Game 1 with a home run off Derek Lowe, and Philly chased Chad Billingley in Game 2 with eight runs in the first three innings. After dropping Game 3, the Phillies mounted a late-inning comeback to win Game 4, and then finished off the Dodgers with a 5–1 victory in Game 5. Philadelphia was headed to the World Series for the first time since 1993.

Pat the Bat was anything but that in the World Series, going hitless in his first 15 at-bats. But in the biggest spot of the Fall Classic for him, he delivered a double off of Tampa Bay's JP Howell to start the bottom of the seventh in Game 5. The Phils led the upstart Rays three games to one, and were now in position to capture their first title in more than 20 years. Pat was pinch-run for by Eric Bruntlett, who scored the go-ahead run on a single by Pedro Feliz. Two innings later, Brad Lidge closed the door on the Rays. Pat rushed the field from the dugout with his teammates. His joy was undeniable.

Pat has fallen short of the elite slugger status once predicted for him. However he has established himself as a mature and patient hitter, and a clubhouse leader. His steadying influence on a young, dynamic team had a lot to do with Philadelphia reaching the World Series. With his contract expiring in 2008 and the Phillies primed to establish themselves as a mini dynasty in the NL East, the team will have a tough decision to make this winter.

Where Pat ends up is anybody's guess. Regardless of that outcome, he has shown that he now knows what happens when you try to play beyond your limits. That's quite significant for him. It used to be that Pat didn’t think he had any.

PAT THE PLAYER

Pat is surprisingly nimble for a man his size. He is also deceptively fast. Both traits are the result of years of flexibility training. Pat is not a threat to swipe a base, but he has taught himself to be a good instinctive runner who can score from first on a double. He has also turned himself into a solid outfielder. While he occasionally takes bad angles on balls in the gap or down the line, he gets a good jump at the crack of the bat and has better-than-average range. For a leftfielder, he has a strong arm.

Pat is no shrinking violet. He says what’s on his mind, and sometimes gets himself in trouble. Yet he has been well-liked and respected everywhere he has played. No one plays harder than he does. Indeed, Pat is a leader in the old-fashioned mold. He works tirelessly at his craft and he puts his money where his mouth is.