Randy Johnson biography

Date of birth : 1963-09-10

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Walnut Creek, California

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2010-11-02

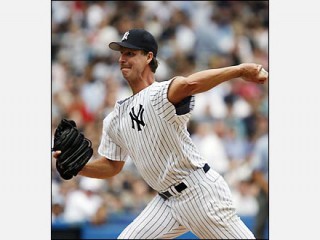

Credited as : Baseball player MLB, pitcher with the Arizona Diamondbacks ,

1 votes so far

Randy was a happy child. He enjoyed joking and talking with his friends and was an active participant in his classes at school. Randy was also a keen observer of the world around him, which led to an interest in photography.

Tall and gangly, Randy was hard to miss as a kid. He towered over other children his age, but was very agile and coordinated at the same time. Not surpisingly, Randy dominated in sports.

His size made him a natural in basketball, but baseball was his first love. Randy was the only boy around who could make a ball hiss when he threw it, and no one wanted to face him in pickup games—not just because of his speed. The youngster had little control over his deliveries to plate. Standing in against him was a test of bravado.

Bud—who stood 6-6 himself and was an avid softball player and a former ski jumper in his native state of Minnesota—believed Randy could harness his size and become a great pitcher. On summer evenings, after leaving his security job at Lawrence Livermore Labs, he would grab a glove, squat down on two creaky knees, and catch Randy’s wild stuff.

Randy worked on his pitching in his driveway, throwing tennis balls at a strike zone he had taped on the garage door. He usually pretended he was Vida Blue, the young A’s lefthander who won the Rookie of the Year and Cy Young Awards in 1971. Randy threw so hard that he loosened the nails in door. After some of these throwing sessions, Bud would hand Randy a hammer so he could drive them back in.

The Johnsons encouraged Randy to hone his pitching skills in Little League. In the spring of 1972, the 8-year-old grabbed his glove and walked over to tryouts at the local athletic complex. When he got there, he saw more than a hundred kids spread out over half a dozen diamonds. He did not recognize any friends or classmates, and a lot of the boys looked older. He wasn’t sure he had the right paperwork or ID and ran home in tears. Carol walked Randy back to tryouts and got him signed up. With a little coaching, he became the best pitcher and hitter in his age group. Within in year, he was moved up two levels.

Throughout elementary school, Randy liked being one of the “big kids”—by sixth grade he was pushing six feet. But when he sprouted seven more inches during junior high, he became aware of the fact that people were gawking at him. The once outgoing boy became shy and withdrawn as a teen. He spent less time with friends and more time with his camera.

Randy eventually found his niche at Livermore High School, where he became the star of the baseball and basketball teams. In hoops, despite his growth spurt (he was now 6-8), he had maintained his coordination. Twice for teh Cowboys, he led the East Bay Athletic League in scoring twice. On the baseball diamond, Randy’s herky-jerky motion and 90 mph fastball—delivered with a whiplike three-quarter motion—was virtually unhittable. And often uncontrollable. He began experimenting with a slider at this point, but it rarely found the plate.

Fans sometimes laughed at Randy’s uniform. His pants ended around his knees, and his jersey came untucked after each pitch. Opposing coaches, looking to rattle Randy, would demand that umpires make him tuck it in several times an inning.

The scouts who came to watch Randy called him Ichabod Crane—it would be another six or seven years before he became the “Big Unit.”

When Randy had everything going, he was one of the best young pitchers in the country. He often struck out 10 or more batters a game. In 1982, as a senior playing for coach Eric Hoff, he fanned 121 in 66 innings of work. In his final outing for Livermore, against Dublin High, he pitched a perfect game. It was only the fourth win of the year for Randy, however. The Cowboys didn’t have much hitting, so when he walked in a couple of runs, he often got hung with the loss.

In the June draft, Randy was selected in the second round by the Atlanta Braves. The team offered him a $50,000 signing bonus. Bud and Carol pointed out that beyond that first check, there were no guarantees in pro ball. Coach Hoff pleaded with Randy to consider college ball so he would have time to develop. With scholarship offers on the table from several top schools, he decided to go the college route and trade his fastball for an education. Randy chose the University of Southern California, a powerhouse program during the 1970s, with a great reputation for sports and academics.

Randy was in heaven in USC. He played both basketball and baseball, found a wide circle of friends, and immersed himself in his new major, fine arts. Randy shot for the school paper and a local rock magazine, and really enjoyed the creative opportunities his classes offered. He also pitched well for the Trojans, winning 10 games and saving five in his first two seasons.

As Randy headed into his junior season in the spring of 1985, most experts believed he was ready for a breakout year. Baseball America ranked him as the fourth-best pitcher in college ball. Unfortunately, the pressure got to Randy, and he did not deal with adversity well. When umpires squeezed him or his fielders made bonehead plays behind him, he would lose his cool.

There was a lot of standing and waiting when Randy was on the mound. He led the nation in walks with 104 in 118 innings. Baserunners also stole on him all the time because of his complex delivery. Randy won just six times in 26 games for the Trojans, and USC finished with the worst conference record in Pac 10 history. Randy was embarrassed and angry about his season, and vowed to make up for it as a senior.

That June, no one was more surprised than Randy when the Montreal Expos took him with their second pick in the draft. He was the second lefty selected, after Joe Magrane of Arizona, who was tabbed with the 18th pick by the St. Louis Cardinals. Randy was the 34th overall pick.

ON THE RISE

Randy was hardly sold on the idea of a pro career. He half-believed he would be at war with his own body (now at its full length of 6-10) as long as he remained on the pitcher’s mound. That gave him incentive to stay in school and get his degree. Baseball was driving him crazy at this point, anyway. But the Expos convinced him that if he could get a handle on his emotions, they could get a handle on his mechanics.

Randy signed a contract, banked his bonus check, and headed off to his first pro assignment in Jamestown of the New York-Penn League. He went winless in eight starts. Manager Ed Creech told him not to worry. The goal for his first pro season was to find a pitching motion that he felt comfortable with, and then build on his confidence as he rose through the minors.

The Expos felt strongly enough about Randy’s potential to put him into a regular rotation in 1986. He pitched for West Palm Beach of the Class-A Florida State League, under manager Felipe Alou. Some days Randy was terrific, and some days he was horrific. Alou and his staff worked on Randy’s mechanics, trying to iron out the kinks in his delivery—no easy task for a guy who would stood nearly seven feet tall. Randy made 26 starts and won eight of 15 decisions. He led the league in walks, but his fastball—and a rapidly developing slider—were sharp enough to limit batters to a .211 average.

Randy spent the entire 1987 with Jacksonville of the Class-AA Southern League. He pitched deeper into games and went 11-8 with a league-high 168 strikeouts. His control was still a problem, but the team definitely felt he was making progress. The only worrisome thing was how easily Randy lost his focus when things didn't go his way. Although such emotional breakdowns were not unusual in the minors, the Expos expected more from a guy coming out of a major college program like USC.

Randy went to spring training in 1988 hoping to earn a promotion to Montreal's Class-AAA team in Indianapolis. He had an impressive spring and claimed a spot in the Indians’ rotation under coach Joe Kerrigan, who had also tutored him the year before. Randy credits Kerrigan—a tall, lanky hurler himself—with refining his delivery.That season, Randy also met his future wife, Lisa, at a charity golf event. She stood six feet tall and managed a photo shop.

The Expos were planning to promote Randy midway through ’88. That plan got sidetracked during a June game when a batter lined a ball of his left wrist. Believing he had suffered a career-threatening break, Randy got so angry that he punched a bat rack on his way to the trainer’s room. When the x-rays came back, they revealed only a bruise on his left wrist—but his right hand was broken. The team, which had always questioned Randy’s maturity, was furious. He didn’t realize it at the time, but in a lot of minds within the Montreal organization now considered him expendable.

Randy eventually made his major-league debut that year, on September 15. He started four games over the final month and won three times, striking out 26 batters and walking only seven in just under 30 innings. Most fans penciled him in for a starting slot in 1989, as did Montreal manager Buck Rodgers.

Touted as a possible Rookie of the Year candidate when the season started, Randy struggled in his first few outings and was sent back to Indianapolis. He was averaging a hit, a walk and a strikeout an inning, and his ERA stood at a robust 6.67 when the Expos finally pulled the plug.

Montreal, meanwhile, was off to intriguing start. Dennis Martinez, Bryn Smith, and Pascual Perez were all reliable veterans coming off good seasons, and Kevin Gross, obtained over the winter for Floyd Youmans and Jeff Parrett, had a big upside. By throwing Randy in the mix, the Expos were hoping to catch lightning in a bottle. Locked a tight race in the NL East, however, the Expos had to make a move for a proven winner. On May 25, the team packaged Randy with pitchers Brian Holman and Gene Harris for Mark Langston of the Seattle Mariners. Coming off a great year for a horrible team, Langston was soon to be a free agent, and thus was an extravagance for the lowly M’s.

Once Randy arrived in Seattle, he finally started pitching the way everyone knew he could, though his numbers didn't necessarily show it. Mired in a losing streak, he sought the advice of some legendary flamethrowers, including Tom Seaver and Nolan Ryan. In his next-to-last season with the Rangers, The 45-year-old Ryan mentioned to Randy that he was landing on his heel when he strode toward home plate. Ryan suggested that he try landing on his foot. Texas pitching coach Tom House concurred. This, they said, might be the key to the consistency that had eluded Randy.

After tinkering for a couple of weeks, everything began falling into place. At one point, Randy hit 102 mph on the radar. With his fastball hitting spots and his curve and slider bending over the corners, Randy finished the year strong. Over his final 11 starts, he was 5-2 with a 2.65 ERA, giving up a mere 47 hits while averaging 10-plus strikeouts a game. His last start was an eight-inning performance against the Rangers in which he fanned 18. Randy finished 12-14 and led the AL with 241 strikeouts in 210 innings. He also led the league in walks for the third time, with 144.

That winter, while Randy was flying home to visit his parents at Christmas, his dad suffered an aortic aneurysm. He was dead before Randy could get from the airport to the hospital. Randy laid his head on his father’s chest and sobbed.

Randy decided to quit baseball. Over the next few days, his mother talked him out of it. Randy eventually turned to religion, becoming more serious about Christianity. He drew a cross and his father’s name on his glove, and to this da,y he still looks at it for inspiration in tough spots. Randy also decided to make his longtime relationship with Lisa official. After he was convinced she knew what she was getting into, they married and later had four children, Samantha, Tanner, Willow and Alexandria.

Randy put it all together in 1993, and the Mariners rebounded under their fiery new manager, Lou Piniella. Randy’s heater touched 100 mph on the gun a number of times, and he perfected what was universally hailed as the game’s best slider. He was murder on lefties, holding them to a sub-.200 average and plunking more than a dozen of them during the year. During the All-Star Game, he scared John Kruk so badly with an inside pitch that the Philly lefty simply waved at his next delivery and walked back to the bench.

With the exception of a few poor mid-season starts, Randy was dynamite in ’93. He went 19-8 with a 3.24 ERA and fanned 308 batters. The key number was his walks total. He issued just 99 passes.

The Mariners, meanwhile, were slowly coming together. They won 82 games in a division that now lacked a dominant team. Although they finished third, the M’s had an exciting nucleus of proven young veterans. The only thing that kept them from challenging the Rangers were injuries to Edgar and Tino Martinez, and a sore elbow that limited Dave Fleming’s effectiveness.

Over the winter, there was much conjecture about the 1994 Mariners. With the new three-division format, they would be grouped with the Rangers, Oakland A’s and California Angels. Could Seattle challenge for the division title? Some felt that by trading Randy, the M’s could plug every hole in their roster. Instead, Seattle dealt Omar Vizquel to the Cleveland Indians for Felix Fermin and Reggie Jefferson. Fermin was a good all-around player who would keep the shortstop job warm for teenager Alex Rodriguez, while Jefferson possessed a tantalizing talent that had as yet gone unrealized. The team also got cash from the Indians, which enabled them to give Randy a raise.

Seattle went to war with its core group and got good seasons out of both Martinezes, as well as Fermin and Jay Buhner. Keny Griffey had a breakout campaign. In fact, he was leading the league in homers with 40 when a strike ended the schedule after 112 games. Pitching was a problem for Seattle, however, and they played most of the year 10 games under .500. Still, in the woeful AL West, a 49-63 record left them only two games shy of a playoff berth.

Randy was the lone bright spot on the Seattle staff, going 13-6 with a 3.19 ERA and a major-league best 204 strikeouts. His four shutouts and nine complete games topped the AL. Nevertheless, Randy endured much of the blame for the team’s sluggish performance, especially after he won just twice in his first seven starts and had a 6.00 ERA. Randy turned it around after that, winning 11 times and hurling 29 straight scoreless innings at one point. Every other starter got hammered, however, and new closer Bobby Ayala gave Piniella nightmares despite saving 18 games. The Mariners seemed just a player or two away from contending.

Once again, Randy was the subject of trade rumors over the winter, and once again, he was on the mound for the M’s on Opening Day. Although the starting staff was still a mess, the offense was firing on all cylinders, with the two Martinezes, Buhner, Mike Blowers (a pickup from the New York Yankees) and new second baseman Joey Cora having career years. The only thing that prevented the Mariners from moving ahead of the Rangers and Angels was a broken wrist suffered by Griffey when he slammed into the outfield wall.

In early September, the AL West looked like a lock for the Angels, while the Mariners, Rangers and Yankees battled for the Wild Card. But an amazing stretch run by Seattle boosted the club in the the division race,. The M's wound up finishing the year tied with California. With New York eeking out the Wild Card, it set up a win-or-go-home one-game playoff between the Mariners and Angels. Randy, who was 17-2 at that point, blew California away to send Seattle to its first-ever playoff series.

MAKING HIS MARK

Randy’s final regular-season numbers for 1995 ranked among the best ever. He went 18-2 in a strike-shortened season, striking out 294 in just over 214 innings—then the best ratio in history. Pitching under pennant pressure, he learned to rely on his off-speed pitches as much as his fastball and his control was awesome. When Randy felt the tank running dry in late-inning situations, he dropped from his usual three-quarters delivery to traditional sidearm, which confused hitters enough to record a few more outs before the bullpen came on. Over the course of the season, lefties hit just .129 against him, while righties managed a .209 mark. He was a no-brainer for the Cy Young Award.

Randy was spent by the time the Yankees came to town for Game 3 of the Division Series. The Mariners had dropped two wild games in Yankee Stadium, and their backs were against the wall. Randy labored through seven innings to earn a 7-4 victory, with mid-season pickup Norm Charlton sealing the deal. Seattle won Game 4 to even the series, and then rallied from a 4-2 ninth-inning deficit in Game 5 to send the contest into extra innings. With the Seattle bullpen drained, Piniella looked to Randy—pitching on two day’s rest—to get the team to the ALCS. He hurled three valiant innings, but gave up a run in the top of the 12th. Incredibly, the Mariners scored twice on an Edgar Martinez double in their half to pull off a memorable victory. With gutsy wins in two of the final three games, Randy had almost singlehandedly delayed the new Yankee dynasty for a year.

Randy pitched well in two starts against the Indians in the ALCS, but Charlton got hammered after he left both games. The Tribe won the series in six games denying Seattle its first pennant. Randy’s final numbers for ’95, including the postseason, were 20 wins and 323 strikeouts.

The 1996 season was one of pain and frustration for Randy. After winning five games early in the year, he went on the DL with a herniated disk. He returned to throw a few innings of middle relief and then called it a season and underwent surgery in September. The Mariners, led by 40-homer seasons from Griffey and Buhner—and a batting title from their rookie shortstop Rodriguez—fell just short of a division title. A dozen more wins from Randy could have easily been the difference in their race with the Rangers.

Randy made up for the disappointment of '96 with a remarkable 1997 campaign. He registered a pair of 19-strikeout performance and fanned 14 or or more on four other occasions. His ERA was under 2.00 most of the season, and the only thing marring his campaign was a bruised middle finger suffered in an August game. Randy finished at 20-4 with 291 strikeouts in 213 innings and a 228 ERA. How he finished second in the Cy Young voting to Roger Clemens, who went 20-7 for the last-place Toronto Blue Jays, was one of baseball’s great mysteries.

There was nothing mysterious about the way Seattle won its division in '97. Six Mariners clubbed 20 or more homers, including Griffey’s league-high 56. Behind Randy, veterans Jamie Moyer and Jeff Fassero combined for 33 wins, while the bullpen held its own with a closer by committee set-up.

Unfortunately for the M’s, Randy was still bothered by his sore hand when the ALDS rolled around. He suffered a pair of losses in a series shellacking by the Baltimore Orioles.

Randy went into 1998 with free agency looming at season’s end. The Mariners, quietly worried about his age and recent injury history, made no overtures to sign him. When the team failed to contend in a weak division, Randy began to lose interest and his record reflected it. He was 9-10 with a 4.33 ERA as the trade deadline approached. With literally minutes to go on July 31st, he was dealt to the Houston Astros for shortstop Carlos Garcia and pitcher Freddy Garcia, both blue-chip prospects.

The trade rejuvenated Randy. Dropping in on the NL Central pennant race, was the best pitcher in baseball over the last two months. He won 10 of 11 decisions and twirled four straight shutouts in the AstroDome. Randy’s final numbers for the year were 19-11 with 329 strikeouts, six shutouts and a 3.28 ERA.

The Astros won 102 games and put Randy on the hill for the NLDS opener against the San Diego Padres. He pitched well enough to win, but Kevin Brown stymied the Houston bats in a 2-1 classic. The teams split the next two games, and Randy was sent out again in a must-win situation. Once again, the normally potent Houston offense was limited to a run, this time by Sterling Hitchcock—a former Seattle teammate of Randy's —and the Astros were sent packing. Randy struck out 17 Padres in 14 innings of work and fashioned a 1.93 ERA, yet all he had to show for his troubles was a pair of postseason losses.

Ironically, the Astros decided to let Randy walk after the season. They had given up Guillen and Garcia thinking they would get a pitcher who could help them down the stretch, and who also would be affordable that winter. With his great second half, Randy had priced himself out of the Houston budget.

Randy’s next address was Phoenix, where he became a member of the Arizona Diamondbacks, thanks to a four-year deal worth $52 million. Other suitors included the Rangers, Angels and Los Angeles Dodgers. The D-Backs, owned by Jerry Colangelo, had been in business all of one year. Constrained by the NBA salary cap as the owner of the Suns, Colangelo was like a kid in a candy store. Besides Randy, he added Steve Finley, Tony Womack, Luis Gonzalez and Todd Stottlemyre to a club that already boasted veterans Matt Williams, Jay Bell and Andy Benes.

With Buck Showalter at the helm, the Diamondbacks ran away with the NL West in 1999, winning 100 games. Randy chalked up 17 of those victories (against nine losses), and led the league with 364 strikeouts and a 2.48 ERA. The numbers told only part of the story. The Arizona bullpen blew five leads Randy entrusted to them, and in many of of his defeats and no-decisions, the D-Backs failed to score more than two runs. It was still one of the most dominant seasons in major league history, and Randy was rewarded with his second Cy Young.

Despite pitching more than 250 innings, Randy did not fade as the season wore on. Thus, he answered any questions about his age or durability. Only in the postseason did he seem human. In the Division Series, as the Wild Card Mets pecked away at him in the opening game and scored a shocking 8-4 triumph. New York won two of the next three, denying Randy a second shot at them.

The Diamondbacks failed to make the playoffs in 2000, despite the stretch-run addition of Curt Schilling and another jaw-dropping season from Randy. He went 19-7 with a 2.64 ERA and 347 strikeouts to claim another Cy Young. He practically locked up the trophy in April, when he won six times and gave up less than a run a game. The D-backs failed to capitalize on this kick-start, eventually falling a dozen games behind the San Francisco Giants in the NL West and coming up well short of the Wild Card.

The 2001 edition of the Diamondbacks put the club back in the mix, thanks to the additions of productive and popular veterans like Mark Grace and Reggie Sanders. With Randy winning 21 and Schilling going for 22, Arizona had just enough to outlast the Giants and Dodgers for the NL West crown. Randy led the league with a 2.49 ERA, struck out 20 batters in a game against the Cincinnati Reds, and finished with a mind-blowing 372 Ks in 250 innings. Again, he was an easy choice for the Cy Young, his third straight.

Heading into the postseason, the Arizona pitching staff was basically a two-man show, with tricky Miguel Batista spelling Randy and Schilling. New manager Bob Brenly, a former big-league catcher, was comfortable with this set-up and played his hand brilliantly.

Schilling outdueled Matt Morris and the St. Louis Cardinals in the opening game of the Division Series, 1-0. Woody Williams next outpitched Randy in Game 2 to even the series. Batista held St. Louis at bay in Game 3, which enabled Brenly to start late-season addition Albie Lopez in Game 4. Lopez lost, but Arizona still had its two best pitchers rested for the decisive Game 5. Randy’s services were not needed, as Schilling authored his second masterpiece, a 2-1 complete game victory on a ninth-inning run off St. Louis reliever Steve Kline.

Randy started the opener of the NLCS and struck out 11 in a 2-0 three-hitter against Greg Maddux and the Braves. Batista nearly stole a victory in Game 2, but the Atlanta bats awoke in time for an 8-1 win. Schilling won Game 3, and then Lopez and five other pitchers combined on an 11-4 shellacking to give Arizona a two-game edge. Randy struck out eight more Braves and slammed the door in Game 5 to send the Diamondbacks to the World Series.

Arizona hosted the first two and last two games of the 2001 World Series, yet were considered underdogs against the Yankees, winners of three consecutive championships. Schilling altered the odds with a three-hit victory in Game 1, and Randy gave the D-backs a two-game advantage with a three-hit shutout one night later.

The Yankees, summoning the spirit and resiliency of their city after the 9/11 attacks, took all three games in the Rbonx, each in dramatic fashion. In two of the games, Arizona actually held the lead with two outs in the ninth.

When the series returned to Arizona, Brenly put the ball in Randy’s hand, with Schilling held in reserve. The Big Unti cruised to an easy 15-2 victory to force a Game 7. In the finale, Schilling pitched into the eighth, but left down 2-1. Randy pitched a scoreless ninth, and then watched from the dugout as the Diamondbacks rallied for two unlikely runs against Mariano Rivera to win the title.

Randy was masterful all series long, posting three wins, 19 strikeouts and a 1.04 ERA. Schilling, who also pitched beautifully, shared the MVP with him.

The Diamondbacks were favored to repeat as NL pennant winners in 2002, and they did their part in the regular season with 98 wins and another division title. Randy had the best year of his career at age 38, leading the league with 24 wins, 334 strikeouts, 260 innings pitched, nine complete games, an .828 wining percentage and a 2.32 ERA.

Against the Cardinals in the Division Series, the D-Backs seemed to lack focus. Randy was ambushed in Game 1, giving up five earned runs in six innings in a 12-2 blowout. When the Cards topped Schilling 2-1 in Game 2, Arizona fans could feel the season slipping away. Two days later, in St. Louis, Batista gave up four early runs and the Cardinals swept Arizona, 6-3.

The big contracts Arizona had been doling out came back to haunt the franchise in 2003, and the club started looking to trim payroll. The D-backs were still competitive, winning 84 games. That wasn’t nearly enough to catch the front-running Giants, and Arizona fell well short of the Wild Card, too.

A healthy season from Randy might have helped, but his right knee began aching in spring training and he underwent arthroscopic surgery in April. It was July before he saw any serious action. Randy was not 100 percent until his last five starts in September. Landing tentatively on his right knee, he was unable to get the same snap on his slider, and lefties hit over .300 against him. Randy began employing a split-finger pitcher he had developed a couple of seasons earlier, but that had limited effectiveness.

Looking to redeem himself in 2004, Randy knew many thought his career had finally hit the skids. Had all those innings, and all those pitches finally caught up with him? The beauty of his situation—or so he thought—was that as soon as he proved he was back to full health, he would likely be traded to a contending team.

As he expected, Randy turned in a wonderful season, but the D-Backs went from bad to worse as the year progressed. Schilling had left for Boston in the off-season, and the team’s major winter acquisition, Richie Sexson, ruined his shoulder on a check swing in May. Brandon Webb, a rookie revelation the year before, lost the sink on his sinker. Jose Valverde, the closer-in-training, was injured for much of the year. And stalwart Finley was traded away after carrying the offense for much of the spring. For the season’s last three months, Arizona basically played kids.

Working with little offensive or defensive support, Randy just kept at it. On May 18, he threw a perfect game against the Braves, striking out 13 batters along the way. He registered his 4,000th career strikeout in his final June start and surpassed Steve Carlton as the top southpaw in that category on his way to 290 for the season. As the trade deadline neared, the D-backs dangled Randy, but the club did not get the deal it wanted from his most ardent pursuer, George Steinbrenner. The Yankees would have given up the farm for Randy, but there wasn’t anything on the farm Arizona wanted. He finished out the year for the D-backs, going 16-14 with a 2.60 ERA. Amazingly, Arizona won just 35 games aside from Randy’s victories.

The 2004 winter meetings came and went without a deal for Randy, who remained on the trading block as teams snapped up free agents and better determined their pitching needs and salary constraints. A trade to the Yankees seemed imminent prior to Christmas, but as the new year dawned, Randy was still a D-Back.

The much anticpated deal was finally consummated in January. New York sent pitchers Javier Vazquez and Brad Halsey, catcher Dioner Navarro and $9 million to Arizona. In return the Yankees got one of the few hurlers who could out-pitch Boston's Schilling in a big game. Randy also fattened his wallet, signing a $32 million, two-year extension.

In a big market for the first time in his career, Randy faced new pressures with the Yankees. He was expected to do two things in pinstripes—beat the Red Sox and pitch lights-out in the postseason. His stay in New York got off to a rocky start after an altercation with a photographer. Randy apologized and then focused on the 2005 campaign.

The strain of media spotlight, however, continued to be a problem for Randy. Whether he pitched well or got hammered, reporters surrounded his locker every day. He saw the constant attention as a nuisance, something that kept him from doing his job. New York fans sensed this, which added to the stress Randy experienced.

Still, he managed to produce when the Yankees needed him. In fact, Randy fashioned a 5–0 record against the hated Bostonians. It was rare, however, that he took the mound with his best stuff. AL hitters learned to lay off his slider in the the dirt, and his fastball didn't seem to explode from his hand at it had in the past. Randy finished the year at 17–8 with a 3.79 ERA and 211 strikeouts, which placed second in the league. He was also touched for an uncharacteristic 32 homers.

Randy's shortcomings were magnified in the postseason. The Yankees faced the Angelsin the Division Series and split the first two games. Randy took the mound for Game 3 in Yankee Stadium. Los Angeles chased him in the fourth, slamming two home runs and scoring five times on their way to a pivotal 11–7 win. Three days later, Randy entered Game 5 in relief of Mike Mussina and pitched well, but it was too little too late. New York went down 5–3.

Randy won 17 games again in 2006, but he pitched with back pain all year long. Some days he was brilliant, other days he was not. His ERA of 5.00 was testament to an inconsistent season. Randy's discomfort was attributed to a herniated disk. In September, he received treatment so that he would be ready for the playoffs. He started Game 3 on the Division Series against the surprising Detroit Tigers and gave up five runs. Kenny Rogers, meanwhile, blanked the over-anxious Bronx Bombers. Once again, it was a crucia contest, and Randy did not deliver. It was his last game in pinstripes.

The Yankees dealt Randy back to the Diamondbacks for the 2007 season. He requested the trade after his brother passed away. The pressures of another year in New York, Randy felt, would be too much on top of this family tragedy. He wanted to go home.

Randy became the elder statesman on an exciting young team. The D-Backs had good position players and a strong bench. Brandon Webb was a full-fledged ace, and Valverde finally fulfilled his potential as a lights-out closer. In the wacky NL West, Arizona seemed to have found the perfect balance between win-now and build-for-later. The team won the division and shocked the Chicago Cubs in the NLDS before falling to the Colorado Rockies in the NLCS.

Unfortunately, Randy was not part of the fun. He appeared to have recovered nicely from surgery on the disk that had troubled him the year before, throwing well in late April and May. But he hurt his back sliding in a June game. By the end of the month, his season was finished. The pain had returned, and this time the disk was removed entirely.

Will Randy return to the mound? If so, will fans see the dominant hurler of old, or a not-so-Big Unit? The answer to these questions may determine the fate of the Diamondbacks in 2008, but they won't have any impact on a career destined for the Hall of Fame.

RANDY THE PITCHER

Anyone familiar with the physics of baseball can see the normal rules don’t apply to Randy. Unlike other power pitchers, he doesn't generate velocity from his legs, but from a strong and coordinated upper body and a whip-like motion that generates tremendous leverage and speed. Where Randy’s legs come into play are in his release point and follow-through, which means he still has to maintain consistency with his lower body.

Randy’s fastball, delivered from a tangle of arms and legs, is what strikes fear into opposing hitters. It is his awesome slider, however, that gets them out. Over the last decade, he has essentially become a control artist who happens to have a 97-mph fastball. A splitter and two-seamer developed in his late 30s give him two other pitches to rely on—often employing them to change speeds—particularly when he doesn’t have his best stuff.

One of the things that defined Randy as an elite hurler was the fact he could win without his good stuff. Of course, he almost always found his good stuff by his next start. Today, Randy is very self-aware as an athlete. That used to be his Achilles heel, but over time it has become a strength. With his back a huge question mark, it is difficult to predict how long Randy can pitch dominantly, or whether he can pitch at all.

EXTRA

# Randy finished his college career at USC with a 16-12 record in three varsity seasons.

# The player taken by the Montreal Expos a round before Randy in 1985 was Pete Incaviglia of Oklahoma State.

# In 1988, Randy was named the American Association’s #3 prospect behind Mike Harkey and Gary Sheffield.

# When Randy and Ken Griffey, Jr. were named to the All-Star team in 1990, it marked the first time in Seattle franchise history that the team had two All-Stars.

# In 1991, Randy became one of the few full-time starters in history to give up more walks (152) than hits (151).

# After making the minor change to his mechanics Nolan Ryan suggested in 1992, Randy also found that he finished his pitches in much better fielding position.

# In 1993, Randy recorded his first save, and changed his number to 45 for a day to honor Nolan Ryan during his retirement ceremony.

# In 1994, Randy became the first pitcher in history to average 10 strikeouts per nine innings four seasons in a row.

# In 1999, Randy became the first pitcher since Nolan Ryan to lead the NL in ERA and strikeouts in the same year.

# Randy would have won the 2000 ERA title but for a disastrous final outing. He finished second to Kevin Brown with a 2.65 mark.

# In 2001, Randy became the first pitcher since Mickey Lolich to win three games in the same World Series.

# Randy is the only pitcher to win World Series Games 6 and 7 on consecutive days.

# In 2004, Randy led the league in opponents batting average (.197) for the fifth time in his career.

# When Randy led the majors in strikeouts for the ninth time in 2004, he broke the record held by Hall of Famer Walter Johnson.

# In 2005, Randy was the first Yankee starter to go undefeated in a season against the Red Sox (with four or more decisions) since Mel Stottlemyre in 1965.

# Randy's favorite catcher with the Yankees was John Flaherty. He went 12–2 with Flaherty behind the plate in 2005.

# Randy was basically a .500 pitcher heading into the season he turned 30. His winning percentage since then is over .700.

# Randy wore #41 during his two seasons with the Yankees. Bernie Williams already had #51.

# Randy has read about all of history’s great pitchers. He says it helps him put his own achievements into perspective.

# Randy still considers Sandy Koufax to be the greatest lefty of all time.

# Randy’s slider is so tough on righties that Barry Larkin once swung and missed at a pitch that went between his legs..

# Randy still plays the drums to unwind. His greatest musical moment was practicing with Soundgarden.

# Randy voiced the animated version of himself on a 2006 episode of "The Simpsons." He was at a convention selling left-handed Teddy bears.