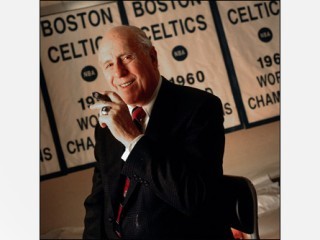

Red Auerbach biography

Date of birth : 1917-09-20

Date of death : 2006-10-28

Birthplace : Brooklyn, New York, United States

Nationality : American

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2010-08-04

Credited as : Basketball coach, coach of the Washington Capitols, and Boston Celtics

0 votes so far

Arnold Jacob "Red" Auerbach , born September 20, 1917 in Brooklyn, New York died October 28, 2006 was a basketball coach of the Washington Capitols, the Tri-Cities Blackhawks, and the Boston Celtics. After he retired from coaching, he served as president and front office executive of the Celtics until his death. As a coach, he won 938 games (a record at his retirement) and nine National Basketball Association (NBA) championships (surpassed only by Phil Jackson). As general manager and team president of the Celtics, he won an additional seven NBA titles, for a grand total of 16 in a span of 29 years, making him one of the most successful team officials ever in the history of North American professional sports. He was one of Marie and Hyman Auerbach's four children. A Russian Jewish immigrant, Hyman owned a deli and later entered the dry cleaning business. Red (who was originally known around his neighborhood as "Reds") got his famous nickname thanks to a shock of red hair that had long disappeared by the time the NBA was being filmed in color. He was a tough kid, who swing first and asked questions later. Red had the heart of a hustler, but was not immune to hard work.

Red grew up in Williamsburgh, just a walk across the bridge from the playgrounds and gymnasiums of the Lower East Side, one of the many evolutionary hotspots for basketball in the 1920s and 1930s. He played his first organized games on the rooftop court at PS 122, and continued onto the varsity at Eastern District High School. Red was quick but not fast, big but not tall. He would grow to a height of only 5-9. Despite intermittent bouts of asthma, he made himself the fittest player on the team by running wind sprints after practice.

Red grew up at a time when Brooklyn actually had a couple of the nations top professional basketball teams. The old American Basketball League was a loose confederation of barnstorming clubs that operated from 1925 to 1931. The Brooklyn Arcadians starred Nat Holman, Rusty Saunders and Red Conaty. Later, the Conaty-led Visitations also called Brooklyn home. Neither team was able to survive the Depression, and pro ball receded into the heartland until the National Basketball League began in the late 1930s.

Despite the local failures, Red exhibited a keen understanding for the business side of basketball. He raised money for his neighborhood team, the Pelicans, by staging a game and dance at the YMHA. During the Depression, this combination was not unusualfans would watch the game from above on the running track, then move to the dance floor to finish off the evening. Red rented the building and hired the band, which was led by future comedian Alan King.

In Reds senior year at Eastern, he was named Second Team All-Brooklyn by the World-Telegram. He often boasted of this achievement among his NBA All-Stars, typically drawing a derisive response. Red would point out that there were more players in Brooklyn in the 1930s than in the entire state of Indiana.

Never much of a student, Red nevertheless had a planafter graduating in 1935, he decided to make a career of coaching and teaching basketball. He hoped to get a scholarship to Columbia, which had a good basketball team, but was rejected. He did not apply to NYU because the school compelled its athletes to major in business. Red preferred to concentrate on physical education. Nat Holman tried to get him a scholarship at CCNY, but his GPA was too low.

Red ended up at Seth Low Junior College in Brooklyn, where one of his classmates was Isaac Asimov. During a scrimmage at the schools court, he was spotted by George Washington College coach Bill Reinhart, who offered him a scholarship to the D.C. school. Red moved to the nations capital in 1936 and never left.

Reds style of streetball did not go over well with teammates or opponents, all of whom he battled while at GW. By his senior year, however, he was the teams leading scorer. Red also began learning about the advantages of the fast break during his final season. The rebound and long pass, when executed properly, created a 3-2 advantage in transition. The Colonials went 38-19 during Reds three seasons, and beat Minnesota, St. Johns and Ohio State during the 1937-38 season. After these victories, a bid to the NIT Tournament was out of the questionNed Irish did not want a big-time school upset in Madison Square Garden.

Red met his future wife, Dorothy Lewis, while at GW. After graduation in 1940, he stayed on at the school, running the intramural sports program in exchange for allowing him to pursue his Masters degree. He also coached high school ball at St. Albans Prep. The salary from this job enabled Red and Dot to tie the knot. Fro there, he hooked on as a coach and teacher at Washingtons Roosevelt High, where he recruited a clumsy 6-5 teenager named Bowie Kuhn to play for the teamthen cut him a day into tryouts.

Red joined the Navy in 1943 and was transferred to the Physical Instructors School in Maryland. Also in his unit, which was trained to condition Navy fliers, were major leaguers Johnny Mize and Johnny Pesky. Next he was sent to Norfolk, where his old coach, Bill Reinhart, was a commander. Sports was a big deal at the base. Phil Rizzuto and Bob Feller were stationed there, as were college hoops stars Red Holzman and Bob Feerick. Red coached the basketball team, which twice beat the all-African-American Washington Bears. This was quite an accomplishment given that the Bears had won the 1943 World Professional Basketball Tournament in Chicago. The team's top stars were Pop Gates and Chuck Cooper.

Among those in the stands for the victories over the Bears was Mike Uline, an ice-machine millionaire who owned a sports arena in Washington. After Red was discharged in 1946, Uline offered him a coaching job in the newly formed Basketball Association of America. With a wife and new child at home, this was a risky proposition for Red. He had a job at $3,000 a year waiting for him at Roosevelt, and was building the kind of resumé that would have led to a long and rewarding career teaching and coaching high school sports. Red, age 28, demanded a $5,000 salary. Uline agreed, and Red took the BAA job.

With the exception of Uline, all of the BAAs original 11 owners had ties to pro hockey. The concept of the league was to share the arenas in the big NHL and AHL cities, filling those seats with 48-minute basketball games. Maurice Podoloff, president of the AHL, was made BAA president.

Red had a free hand in the assembly and coaching of the Washington Nationals, as Uline professed no expertise in the sport of basketball. From his Navy days, Red understood that the best guards came from the New York metro area, the fast-break players were in the midwest, and the tall trees needed for pivot play were on the west coast. So while the other BAA built clubs from their local markets, Red went shopping nationwide. His starting five in 1946-47 were Navy pals Bob Feerick and John Norlander, John Mahnken, Fred Scolari and Bones McKinney. McKinney was Red's major coup. The UNC star had already promised the Chicago Stags he would play for them, but Red intercepted him on his way through Washington and signed him to a $6,500 contract in a hotel washroom.

This combination of starterssupported by bench players Ivy Torgoff and Bob Gantreeled off 17 straight victories early in the BAA's 60-game schedule and the Caps finished atop the Eastern Division by 14 games over Eddie Gottliebs Philadelphia Warriors. The season ended in frustration, however, when the Stags beat Washington in the playoffs, taking two games in the Caps arena, where they had gone 29-1 during the regular season. The Caps were relocated to the BAAs Western Division for 1947-48 and finished with 28 victories in the leagues reduced 48-game schedule. Only one victory separated the four West clubs, and Washington lost the a play-in game with the Stags 74-70 for their second early exit in two seasons.

The Caps returned to the East in 1948-49 and finished first in the division with 38 wins. This time, they reached the BAA Finals, where George Mikan and the Minneapolis Lakerswho jumped from the rival National Basketball Leaguedefeated them in six games.

Later in 1949, the BAA and NBL merged to become the National Basketball Association. Red, in turn, found himself out of a job. Recognizing that the team would need to rebuild, and having taken the Caps to the Finals, he had asked Uline for a three-year contract, and the owner turned him down. Red took a job as an assistant coach at Duke, and realized almost immediately that college ball was not what he wanted.

A few weeks into the 1949-50 season, Red was contacted by Ben Kerner, the blustery owner of the Tri-Cities Blackhawks. The team played its game in the midwestern cities of Davenport, Moline, and Rock Island. After starting the year slowly, the Blackhawks needed a new coach. Kerner offered Red a two-year deal for $17,000, plus the authority to make trades. He got to work immediately, making trades involving more than two dozen players in his first six weeks at the helm. Tri-Cities played 28-29 ball the rest of the way, as Red filled the roster with better but still marginal talent. It would be the only losing record of his pro coaching career.

It was also his only year with the Blackhawks. When Kerner traded one of Reds favorites, John Mahnken, and informed him of the deal after it was done, Red knew his time with the team would not last.

The 1950-51 campaign found Red coaching the Boston Celtics for owner Walter Brown. Brown had lost a small fortune on the Celtics, and desperately needed someone who understood pro basketball from the backboards to the bench to the boardroom. Reds first act was to not draft Bob Cousy of Holy Cross, the most popular player in New England. Cousy, whom Red called a local yokel, was the kind of flashy player he despised, so he took center Charlie Share instead.

The fans and the press howled, but Cousy went undrafted until Kerner and the Blackhawks picked him up. After refusing to sign with Tri-Cities, Cousy was dealt to the Stags, who promptly folded. He ended up on the Celtics anyway and helped Boston finish second in the East with a 39-30 record. Bones McKinney was also on the '50-51 team, as was Chuck Cooper (who today is hailed as one of the NBAs African-American pioneers).

Ed Macauley, a mobile center who dumped in 20 a night, was the scoring star of the Celtics. But it was Cousys behind the back dribbling and no-look passes that electrified crowds at the Boston Garden, and eventually made a believer out of Red. The tipping point was the point guard's ability to find open teammates, which forced enemy defenders to stick close to their men at all times. The Celtics made the playoffs, but lost to Joe Lapchicks New York Knicks.

Red added shooting guard Bill Sharman in 1951-52, after his old Washington team went under, and his fastbreak offense began working like a charm. The only thing the Celtics lacked was a dominant rebounder, a deficiency that would keep them from advancing in the rugged playoffs of the 1950s. They lost to Knicks again in 1952 and 1953, and the Syracuse Nationals in 1954, 1955 and 1956. During this time, Reds coaching genius did not go unnoticed. He published an extremely influential book in 1953Basketball for the Player, the Fan and the Coachwhich was translated into several languages and reprinted many times in the 1950s and 1960s, as the Celtics started to roll up championship after championship.

At the end of the 1955-56 season, Red targeted the player he needed to make his strategies work: Bill Russell, who had led the University of San Francisco to 55 straight wins. Boston traded Macauley and rookie Cliff Hagan to the St. Louis Hawks for the rights to Russell. To make sure that Rochester didnt take the center with their #1 pick, Celtic owner Brown offered the Royals owner, Lester Harrison, the Ice Capades free for a week. In the days when no one was making much money on the NBA, this looked like a sweetheart deal, and the Royals selected Sihugo Green.

Once Russell was acquired, Red had to outbid the Harlem Globetrotters for his services. The big man joined the team after the Melbourne Olympics, playing in Boston's final 48 games and leading the league with 19.6 rebounds per game. With Cousy, Sharman, rookie Tom Heinsohn, forwards Frank Ramsey and Jim Loscutoff, the Celtics had an unheard-of six players scoring in double figures. It was at this time that Red established a precedent that would serve him well during the 1960s. On a team of stars, each player had to accept a diminished role, and learn to take their greatest pride in winning.

Bostons now-devastating fastbreak was triggered by Russell, who sealed off the lane with positional defense, shot-blocking and rebounding. Opponents settled for outside shots, which enabled the Celtic guards to release, and Russell often finished the breaks he started with his bullet outlet passes. Boston reached the NBA Finals for the first time in 1956-57, and won a thrilling seven-game series against the Hawks. Russell averaged a remarkable 24.4 rebounds in the postseason. The fantastic finish overshadowed the other highlight of the series. Before one of the games in St. Louis, Red took the court armed with a tape measure, suspicious that the baskets were raised to throw off Bostons shooting. When his old boss Kerner challenged him, he punched the Hawks owner in the mouth.

After dropping the 1958 Finals to the Hawks, Reds men took the NBA title each year from 1959 to 1966. These teams were a dynasty in every sense of the word. One star after another blazed through the Boston Garden, often beginning as a bench player or specialist and then growing into a full-fledged superstar. Even when the team faced game-altering immortals such as Jerry West, Elgin Baylor, Oscar Robertson, and Wilt Chamberlain, the Celtics always had enough weapons to win. Among the teams standouts during this remarkable eight-year championship run were Cousy, Russell, Sharman, Heinsohn, Ramsey, K.C. Jones, Sam Jones, Tom Sanders, John Havlicek and Don Nelson. Driving the dynasty was Red, chomping on his cigar, working the officials, and doing everything under the sun in his relentless quest for victory.

Prior to the 1966-67 season, Red announced his retirement. He became Bostons full-time general manager and handed the reins over to Russell, making him the first African-American coach of a major sports team. Three seasons earlier, Red had fielded the NBAs first all-African-American starting lineup, with veteran Willie Naulls playing in front of Heinsohn. When Red hired Russell, he wasnt looking to break barriers. As he put it, The only guy besides me who can coach Russell is Russell.

The Celtics improved their record under their new player-coach, but fell to Chamberlain and the Philadelphia 76ers in the playoffs. Boston returned to the championship podium under Russell in 1968 and 1969, while Red pulled the strings behind the scenes to retool the team for the 1970s.

He did so by scouting, drafting and signing the likes of Don Chaney, Jo-Jo White, Paul Westphal and Dave Cowens. The Cowens pick was an Auerbach classic. Sensing that the tough, mobile center would provide the kind of presence that Russell had, Red scouted him personally during his senior season at Florida State, which had gotten little press because of NCAA probation. All eyes were on Red when he walked into the arena, and he knew it. To throw off other teams looking at Cowens, Red stormed out of a game at halftime saying loudly, Ive seen enough. He then grabbed the Red Head with the teams first pick in the 1970 draft.

The Celtics won the NBA East every season between 1971-72 and 1975-76, and claimed the NBA title in 1974 and 1976. Auerbach engineered deals for veteran rebounder Paul Silas and ABA star Charlie Scott, and groomed his former star, Heinsohn, into a winning head coach. Later in the decade, he hired Bill Fitch, who returned the club to the NBA Finals after a couple of down years.

The Celtics of the 1980s were the last team that truly bore Auerbachs mark. He found role players Cedric Maxwell, Chris Ford, M.L. Carr, Nate Archibald and Gerald Henderson to support emerging stars Larry Bird, Robert Parrish and Kevin McHale. Bird was Reds Russell-like coup. Basketballs Great White Hope, he was a fifth-year senior at Indiana State. The Celtics took advantage of a loophole and drafted him as a junior in 1978, and waited for him to finish his college career. Red had visions of Bird playing in the NCAA Tournament and NBA playoffs the same spring, but Indiana State made it to the national championship game, thwarting this plan. He signed Bird that summer, after a year of waiting, and the Celtics returned to the top of the East with 61 wins in his rookie year.

Red sensed correctly that Bird was the perfect Celtic. He embodied the creativity of Cousy, the shooting of Sharman, Heinsohn and Sam Jones, the intensity of Russell and the workhouse attitude of Havlicek.

The NBA owed Red much for this move. Wracked by financial instability, drug rumors and a decline in fan interest, the league benefited immeasurably from Bird being with the Celtics. The NBAs most traditional franchise had its throwback superstar. Meanwhile, Birds college rival, Magic Johnson, had revitalized the league's West Coast glamour franchise in Los Angeles. These two would elevate the NBA to major sport status again, just in time for Michael Jordan to boost it into the stratosphere.

Interestingly, Red had strongly opposed the three-point shot after the NBA-ABA merger in 1976. But once Bird joined the Celtics, he became one of its most ardent supporters.

The Celtics reached the NBA Finals in 1981 and beat the Houston Rockets for the championship. Guards Danny Ainge and Dennis Johnson came aboard in the early 1980s, helping the Celtics win it all again in 1984 and 1986 under former star K.C. Jones.

The '86 title was Red's 16th as coach, GM and president of the Celtics,. Only Phil Jackson has been able to match his nine NBA championships on the sidelines. Red ran the day-to-day business of the Celtics until the mid-80s. After that, he continued to serve as team president. He held that position until the day he died from heart attack on October 28, 2006.

To the very end, Red was the NBAs master communicator. Regardless of his role with the Celtics, he had the ability to sit down with a player and learn about him as a person and a player. After just a handful of conversations, Red was able to understand what he was all about, and how to motivate him. This skill, as much as any other, defined his genius from basketballs stone age to its modern era.