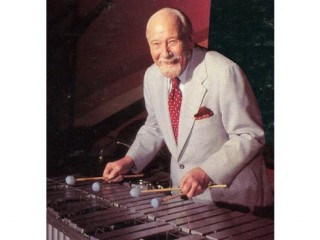

Red Norvo biography

Date of birth : 1908-03-31

Date of death : 1999-04-06

Birthplace : Beardstown, Illinois, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2012-01-05

Credited as : jazz vibraphonist, known as Mr. Swing, Multi-instrumentalist

1 votes so far

"I play the vibraharp," declared Red Norvo in his 1968 interview with Whitney Balliett for the New Yorker. "Of course, I started on the xylophone and marimba in the mid- twenties, and up until then they were vaudeville instruments, clown instruments. They differ from one another chiefly in range.... The [xylophone's] bars, or what would be the keys of a piano, are made of rosewood. The vibraharp [a trade name for vibraphone] has the same keyboard, but it is lower in range than the marimba. It's an electronic instrument and its bars are made of aluminum. It's electronic because the resonator tubes that hang down underneath the bars, like an upside-down organ, have little paddle-shaped fans in them called pulsators that are driven by a small electric motor."

Virtually unaided, Red Norvo lifted the xylophone, and then the vibraharp, from the clown's role to one of jazz prominence. After trading his favorite pony and a summer's hard work for his first xylophone at about age 15, Norvo taught himself to play by ear, studying music rudiments as on- the-job training.

Through constant experimentation with a variety of mallets and techniques, Norvo conquered the physical limitations of the xylophone, transforming it into a melodic, expressive voice in jazz ensembles of all sizes. As virtuoso cornetist and writer Rex Stewart told Down Beat in 1968: "Red's contribution (over and above his being consistently one of the most gifted and communicative players on the vibraharp) lies in the fact that he singlehandedly made the xylophone sound a part of the lexicon of swing. Without question, he must be categorized as a charter member of that select group--the innovators--whom the profession considers immortals."

Norvo began playing professionally in Chicago at 17 as the entertaining leader of a marimba ensemble, the Collegians. Moving to the orchestra of Paul Ash, Kenneth Norville became Red Norvo, thanks to the leader's inability to remember the proper name. Later, as a solo vaudeville act, he added tap- dancing to his playing. At about the age of ten the youngster had been introduced to live jazz by listening to cornetist Bix Beiderbecke, saxophonist Frankie Trumbauer, and especially trumpeter Louis Armstrong on the visiting river boats in Beardstown on the Illinois River. And while he was influenced by the virtuosity of George Hamilton Green and a theater musician named Wentworth on xylophone, Norvo was irresistibly drawn toward jazz. He carried his Victrola and collection of the latest jazz records with him constantly.

Other constant companions were Norvo's innate good taste, his quest for innovation, and his infallible musical ear. In Chicago in 1929 he caught on with the popular orchestra of Paul Whiteman whose vocalist, Mildred Bailey, was to become one of jazz's most celebrated singers. Norvo and Bailey married in 1930, about the time the Whiteman troupe moved its base to New York. Very soon, Norvo began recording with Bailey and other Whiteman musicians, etching his first two sides as leader in 1933 with clarinetist Jimmy Dorsey, pianist Fulton McGrath, guitarist Dick McDonough, and bassist Artie Bernstein.

On these recordings Norvo demonstrated his formidable mallet technique, but it was not until November of that year that Norvo's unique jazz voice, both instrumentally and as a composer/arranger, was recorded. The tunes were Bix Beiderbecke's classic, "In A Mist," and Norvo's own "Dance of the Octopus."

In his The Swing Era, Gunther Schuller rates the former "the most moving and sympathetic performance of that work, including Beiderbecke's own," and the latter "clearly the most advanced composition of the early thirties." In addition to McDonough and Bernstein, Benny Goodman played bass clarinet on this session.

Norvo quickly earned the attention and respect of New York's fertile music community. After leaving Whiteman in 1934, he recorded with the cream of the fraternity: trumpeter Bunny Berigan, clarinetist Artie Shaw, trombonist Jack Jenney, pianist Teddy Wilson, drummer Gene Krupa, saxophonist Chu Berry, guitarist Dave Barbour, cornetist Stew Fletcher, and bassist Pete Peterson, the latter three of whom played in Norvo's performing group on 52nd Street. Among this era's recordings, "Bughouse" and "Blues in E-Flat," done with Berigan and others, stand out as magnificent examples of Norvo's style.

And it was in about 1935 that Norvo met soul mate Eddie Sauter, a Juilliard and Columbia University-trained mellophone and trumpet player, who became more noted for his inventive writing and arranging with Norvo, Goodman, and his own orchestra. Sauter helped shape the sound of the various groups that Norvo led, first an octet, later expanded to 12 pieces with Bailey as vocalist. This amalgam produced a brand of subtle swing that blended Bailey's unique voice with forward- looking instrumental timbres. Richard Gehman and Eddie Condon, writing for Saturday Review, claim this band "is now firmly entrenched in history as one of the finest of all time." In these and other small group contexts, the xylophonist recorded many memorable performances.

Norvo continued as a leader and pacesetter of various groups until 1944, one an all-star aggregation that included trumpeter/arranger Shorty Rogers, trombonist Eddie Bert, pianist/arranger Ralph Burns, and clarinetist Aaron Sachs. During the latter period Norvo switched to vibraharp. After forsaking leadership in 1945 to play with the Benny Goodman big band and sextet, Norvo rarely returned to the xylophone. During 1946 he switched to the exciting Woody Herman band and was also featured with that group's band-within-a-band, The Woodchoppers.

The Norvo/Bailey household in Forest Hills, New York, became a mid-thirties gathering place for musicians, and it was there that the Benny Goodman Trio was born. Norvo loves to tell the story of how Goodman and Wilson began jamming one night when Krupa was a guest and an idle set of drums happened to be available. Krupa sat in; the trio became a musical success and Goodman fixture, later evolving into the quartet with the addition of Lionel Hampton on vibes. Blues empress Bessie Smith, vocalist Lee Wiley, composer Alec Wilder, cornetist Red Nichols, pianist Fats Waller, and Berigan were among the regular guests.

Not all was sweet harmony in the household, however. "Mr. and Mrs. Swing," as they were titled by writer George Simon, engaged in some self-admitted monumental and destructive fights. A 1939 illness caused Bailey's temporary retirement, after which the couple rarely performed together. After 12 years of marriage, during which time Mildred sang for long stretches with Red's band, they divorced. Their relationship remained cordial until Mildred's death in 1951.

In 1947 Norvo moved to California with his second wife, Eve Rogers, the sister of Shorty Rogers, beginning a period of freelance playing in various settings. He returned east in 1949, fronting a sextet that included pianist Dick Hyman, clarinetist Tony Scott, and guitarist Mundell Lowe. This began a period of extensive travel for Norvo, during which he made his first overseas visit (1954), toured Europe with Benny Goodman (1959), and was featured globally with entrepreneur George Wein's groups. He continued switching between the coasts as well, appearing frequently in Las Vegas.

Norvo had long adjusted to performing with 60 percent hearing in one ear. When, in 1968, his "good" ear quit functioning temporarily and required surgery, he feared he would be forced to end his career. Eve died in 1972, and Norvo stayed away from music completely for two years. Returning in 1974, with the troublesome ear somewhat restored, Norvo began a nomadic existence in which he has billed himself as a solo act, rather than as the leader of a specific group, working with able local musicians and relying on his own formidable improvisational gifts.

Always recognized for his ability to bridge varying musical styles while retaining his own voice, Norvo provided leadership in at least two memorable musical forays. The first was 1945's recording session by Red Norvo and His Selected Sextet. When approached by Comet records to organize a session, Norvo insisted upon freedom in choosing both the musicians and the material. He selected Dizzy Gillespie, trumpet; Charlie Parker, alto sax; Flip Phillips, tenor sax; Teddy Wilson, piano; Slam Stewart, bass; J.C. Heard or Specs Powell, drums. Parker and Gillespie represented the cutting edge of bebop, with Phillips leaning toward modernism; the others were identified with the swing era.

So skillfully did Norvo integrate these varying stylists that the four selections--"Hallelujah," "Get Happy," "Slam Slam Blues," and "Congo Blues"--remain as models of inventive transition. As Ira Gitler observed in his Swing to Bop, "It was a time when Dizzy and Bird were becoming more well known but were being put down by some critics. These recordings changed a lot of people's minds.... These recordings made logical to some people, who previously hadn't understood, the connection, the evolution of the music."

The second event was Norvo's formation in 1949 of the prototype trio featuring the obscure Tal Farlow on guitar and Charles Mingus, brought out of retirement from a job as letter carrier, on bass. Of this group, Schuller wrote: "Just as Art Tatum is remembered mostly for his Trio work, so too Norvo is today remembered for the outstanding trio he formed.... The Norvo Trio remains in memory as one of the finest small groups in jazz history."

In The Big Bands, George Simon summed up Norvo's jazz contributions: "He was great in those days ?1936?, he had been great before those days, and he is great today. Of all the musicians in jazz he has remained for me, through the years, the most satisfying of them all; in short, he remains my favorite of all jazz musicians."

Norvo recorded and toured throughout his career until a stroke in the mid-1980s forced him into retirement (although he developed hearing problems long before his stroke). He died at a convalescent home in Santa Monica, California at the age of 91.