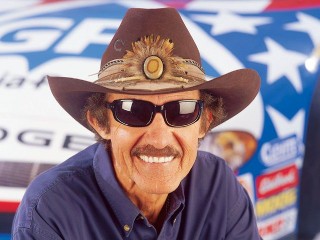

Richard Petty biography

Date of birth : 1938-07-02

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Level Cross, North Carolina, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2010-07-27

Credited as : NASCAR driver and racer, Daytona auto racer,

21 votes so far

Lee was a hard-working truck driver and a skilled mechanic. Where other families struggled to make ends meet, he always seemed to be thinking a step ahead. When Maurice contracted polio, the Pettys were able to handle this added burden without resorting to illegal activities, such as moonshining. Lee was not averse to working on the cars of moonshiners, however. And in this regard, he probably helped a few evade the law.

One of the popular pastimes in the mountains of Western North Carolina in the 1940s was races between moonshiners to see who had the fastest cars. Lee couldn’t resist this kind of challenge, especially if there were a few dollars awaiting the winner. Eventually these contests moved onto dirt ovals and spectators paid a quarter or two to watch. Lee and his brother, Julie, decided to enter a car. They won their first race and received a share of the gate receipts.

But despite this early triumph, the Pettys knew they could not compete with moonshiners, who sent away for special parts to supe-up their cars. Still, Lee and his sons attended the local races, watching and learning all they could about the sport.

In 1948, when Richard was 11, Lee took his boys to Daytona to watch the racing there. Daytona was a Mecca for stock-car racing. There, Lee ran into Bill France, who was planning to bring racing out of the Stone Age and make it a legitimate, legal and well-organized sport. Lee was intrigued. He believed he had no equal behind the wheel.

One year later, Lee packed his family into their car and headed for NASCAR’s first Strictly Stock event in Charlotte. On the outskirts of town, he stopped at a service station, paid the owner a couple of dollars to put his car on a lift, and set it up for the race. The Pettys weren’t planning on being spectators. They planned on winning.

Richard and Maurice served as Lee’s pit crew. Elizabeth watched anxiously as cars spun out and crashed. She hoped they would have a car to drive home. Her prayers went unanswered. On the 108th lap, Lee took a turn too fast and his car tumbled off the track. After he emerged unscathed, all he and the boys could talk about was how they could win these races if they could only get a lighter car.

Among Dick’s major-league heroes was Pirates legend Roberto Clemente. He studied the Pittsburgh outfielder and admired the way he played the tricky right field wall at Forbes Field. Unlike Clemente, Dick was a gifted power hitter. While at Wampum High and in summer leagues, he sent drives to all fields that left teammates and opponents in slack-jawed awe.

A few days later they were working on a used Plymouth in the family “garage”—four poles with a wooden roof, where they also butchered hogs. Lee entered five more races that season and notched his first victory at the Heidelberg Speedway, outside of Pittsburgh. He finished second to Red Byron in the points standings and collected nearly $4,000 in prize winnings.

Lee entered 17 races in 1950, winning one and pocketing more than $5,500. He actually could have won the Grand National driving championship, but France docked him more than 800 points for competing in unsanctioned events. He wound up third in the standings, behind Bill Rexford and Fireball Roberts. When NASCAR expanded to more than events in 1951, Lee competed in 32 and finished fourth in the standings. By the mid-1950s, Lee was among the sport’s elite drivers.

His breakthrough year came in 1954. Lee had developed a driving style designed to win championships, not races. His goal was to drive smart and finish among the leaders, but not risk everything going for the victory. In 34 starts in 1954, he notched 32 Top 10 performances, while taking the checkered flag seven times. This enabled him to out-point Herb Thomas, who won 12 races and earned $8,000 more in prize money.

By this time, Richard and Maurice were seasoned NASCAR pit crewmen. Maurice showed an aptitude for building engines and setting up Lee’s cars. Richard was smart and strong and itching to get behind the wheel himself. Lee quelled Richard’s ambitions by forbidding him to race until his 21st birthday. Until then, he would have to watch and learn.

In the meantime, the Petty boys helped Lee win 19 more races over the next four years, as well as a second Grand National title in 1958. Lee drove an Oldsmobile to seven victories that season and led the points standing from the spring on.

Sure enough, 10 days after he turned 21 in the summer of 1958, Richard competed in his first race, a convertible event in Columbia, South Carolina. He finished sixth. Later during that season, he made nine starts on the Grand National circuit, notching a lone Top 10 finish. His first event at NASCAR’s top tier was in Toronto. On the 55th lap, he drifted in front of Lee, who was on his way to winning the race. Son or not, it was time to teach the kid a lesson. Lee drove Richard into the fence and out of the race.

Richard hit the Grand National circuit fulltime in 1959, driving Oldsmobiles and Plymouths in 21 races. He was a Top 5 finisher six times and ranked 15th in the points standings at the end of the season. That was good enough to earn Rookie of the Year honors. Richard also ran in over a dozen events in NASCAR’s Convertibles division. He won one race and ended up fourth overall. It was the last year NASCAR ran the ragtops.

Richard thought he had his first Grand National victory in June at Lakewood Speedway in Atlanta. He took the checkered flag ahead of his father, but Lee protested the decision, claiming he was ahead of his son, not the other way around. Sure enough, when the scorecards were checked, NASCAR officials declared Lee the winner.

Despite the strides made by Richard, the big news in the Petty garage that year was Lee’s second straight driving championship. He won 11 races in 42 starts and blew away the field for the second year in a row. His biggest victory came at the inaugural Daytona 500, but it wasn’t official for 61 hours because he and Johnny Beauchamp crossed the finish line in a virtual dead heat. Only when newsreel footage was viewed by Bill France was Petty declared champion.

Richard notched his first victory in February of 1960 in a 100-mile event at the Charlotte Fairgrounds. He was trailing Rex White late in the race when Lee gave him a bump, enabling his son to make the winning pass. Richard won again in April at the Virginia 500 in Martinsville. Over the years, he would enjoy great success at this track, taking the checkered flag a total of 15 times. Richard won his third and final race of 1960 in a 99-mile event at the Orange Speedway.

Thogh he posted only three victories, Richard had a terrific year. He finished 30 of his 40 races among the Top 10 and chased White in the standings all summer long. Richard also scored an impressive third-place finish in the Daytona 500, which helped him finish second overall in the standings.

Things might have been different had he not been disqualified from the World 600 for making an illegal entrance onto pit road. Instead of racking up over 3,500 points for his fourth-place finish that day, he ended up with nothing to show for his effort. At the end of the year, White’s margin of victory was slightly more than 3,900 points.

Speedweeks in 1961 was a time the Petty family would rather forget. Both father and son went airborne after crashing through the guardrail at the Daytona International Speedway—Richard during the first 100-mile qualifier and Lee during the second. Richard managed to keep his wheels on the ground and rattled down the embankment. He walked away from his wreck, but Lee sustained career-threatening injuries and was hospitalized into the summer. Neither was able to drive in the Daytona 500 itself.

Richard won two races in 1961 and slipped down to eighth in the standings. His victories came in the Richmond 200 and a 100-miler at Charlotte Motor Speedway. He ran consistently well throughout the year, finishing more than half his 42 starts among the Top 10. Byt this point in his career, he was starting to perfect the driving style that would propel him to unimagined heights—laying back, conserving his resources, reading the race, and learning how to recognize when then gold moment developed where he could make his move.

Richard was also becoming an expert in the art of drafting. He proved this during Speedweeks in 1962 when he finished second in the 100-mile qualifier and the Daytona 500 despite driving a slower Plymouth. In the main event, Richard spent much of the race on the tail of Fireball Roberts’ lightning-fast #22 Pontiac, content to stay there until he had sewn up the number-two spot.

Lee had recovered from his injuries by 1962 but chose to let others drive his #42 Plymouth for much of the season. Bunkie Blackburn drove it to a 13th-place finish at Daytona, and Jim Paschal won two races during a six-race win streak for the Pettys over the summer.

Richard won the other four. The driving championship was a dogfight between Richard, Joe Weatherly, Jack Smith and Ned Jarrett. Weatherly edged Richard on the strength of his nine wins to Richard’s eight. Weatherly was particularly brilliant on short tracks that year.

When Dick was named Rookie of the Year, he felt embarrassed and ashamed. He said years later that it felt wrong to accept an individual accolade after his team had played so hard and come up a game short.

Richard came into his own in 1963, capturing 14 events. His victories included the Gwyn Staley 400 and Virginia 500. He also won his first road race with a dazzling performance at the Bridgehampton Race Circuit on Long Island. He established himself as a NASCAR fan favorite as well. Where Lee could be a little scary for autograph-seekers, Richard was easygoing and always willing to put pen to paper for the ticket-buying public.

In any other year, Richard would have claimed the NASCAR championship. But Weatherly was an animal in 1963. Bud Moore, his team owner, decided to skip the small events and concentrate on the big ones. So for the short-track events Weatherly often showed up at races without a car. He would borrow one from another team, gobble up points, and move on to the next event. He drove for nine different teams during the season and ended up out-pointing Richard even though he won 11 fewer races.

In a way, the championship was decided in February, when Richard failed to overtake Fireball Roberts in the Daytona 500. Roberts ran out of gas twice and had some wild pit stops, but he still finished 27 seconds ahead of Richard. Lee swore he saw seven men go over the wall during one of Roberts' pit stops and lodged a protest, but NASCAR wasn’t about to disqualify a hometown hero. Fireball celebrated his second 500 victory.

The Petty Plymouths had been running at a disadvantage for years. Although Richard had driven skillfully on the big tracks, he had no victories to show for it—all of his wins thus far had come on short tracks. In 1964, the Plymouths packed powerful Hemi engines and the difference was obvious beginning at Daytona. Richard’s qualifying time was 20 mph faster than the year before, and he piloted his electric blue Plymouth Belvedere to an awe-inspiring victory in the Daytona 500.

Richard took the lead on the second lap, consolidated his advantage on lap 52, and held it the rest of the way, flying along the upper groove, where he had made a living over the years in less-powerful cars. Now he lapped the track like a jet fighter.

Richard received his winner’s trophy from Miss Japan as part a NASCAR program to broaden the sport’s appeal overseas. He was overjoyed to have that first superspeedway win under his belt. The only sad part of the day was that his family never left the motel. His wife, Lynda, who he had married in 1958, had to stay with their kids, Kyle and Sharon, who were sick with the measles. She was pregnant with their third child, Lisa, at the time. Richard and Lynda would have four children in all. The last was a third daughter, Rebecca.

The 1964 season included a mind-boggling 62 races—the most ever for NASCAR. It actually started late in 1963. Richard competed in all but one of the Grand National events. He assumed the points lead for good after finishing second at the World 600 and claimed the title by more than 5,000 points. Richard won nine events, and might have made it an even 10 victories but for a blown engine on the final lap of the Volunteer 500 at Bristol. He led almost the entire race before disaster struck.

Richard was delighted with the on-demand power of the Hemi engine. While some drivers were terrified by the speeds being clocked on the high-banked tracks, Richard felt right at home at 180 mph. He said the engine sounded like it was ready to suck in the hood.

As the year wore on, many teams complained that the Hemi should not be allowed in stock car races, since it wasn’t really available in showrooms. Heading into 1965, NASCAR legislated the Hemi engine—and Richard’s beloved Belvedere—out of Grand National competition.

Chrysler responded by pulling out of NASCAR, and the Pettys soon followed. There simply wasn't time to rebuild their team. Instead, Richard decided to try the drag racing circuit. Maurice showed he could build an engine for the quarter-mile, and Richard raced a Plymouth Barracuda nicknamed “Outlawed” at strips around the South,. He lost only six times. On balance, however, the experience wasn’t a positive one. Richard crashed at an event in Georgia and a boy in the crowd was killed. The Pettys were a stock-car family, and they wanted back in.

Fortunately, Petty-less track owners put enough pressure on Bill France to bend the rules and allow the Hemis back in. Richard returned to Grand National competition in the spring of 1965 to find the Ford cars mopping up. By the time he won his first race—the Nashville 400 in late July—Ford had captured 32 straight races. Richard won three more times and claimed a total of seven poles in 14 events. The season was essentially a warm-up for 1966, when a modified form of the Hemi would be allowed back in competition.

The payoff came right away, at the Daytona 500. Richard set a qualifying speed record at 175.165 mph. Speeds in general were up for the race, and after a few laps it became clear that the tires would not be able to handle the added friction. Chunks of tire started smashing windshields. Richard had to pit unexpectedly because of a blistered tire.

By the time Maurice had his brother's car back in shape, Richard was two laps down. He slowly made his way back toward the leaders, driving more aggressively than he would have liked. He knew that disaster could strike at any moment. Richard grabbed the lead for good on lap 113 and from there ran near perfectly. He was a lap ahead of Cale Yarborough when the race was halted two laps early because of rain. Richard had his second Daytona 500. Despite seven pit stops, he had set a record with an average speed of 160.6 mph.

Richard found himself chasing a new rival in 1966, David Pearson. Like Richard, Pearson was superb on the short tracks and smart on the major speedways. In 1966, Richard set a record by winning three consecutive races from the pole. Pearson also established a new mark, with three separate three-race winning streaks.

Richard won eight races in all during the campaign, good for third in the standings behind Pearson and James Hylton. Besides his victory at Daytona, he also won the Rebel 400 and Dixie 400. A hand injury early in the year kept him out of three races, and he was never able to make up the ground he lost.

There would be no lost ground in 1967. In fact, Richard enjoyed the greatest year in American auto racing history. Among his many milestones, he surpassed NASCAR’s all-time win record. His 55th victory came at the Rebel 400 in Darlington. The man he passed was his father. A month later, Richard took the Carolina 500 at Rockingham and seized control of the points race for the rest of the year.

On August 12, he won his 19th race of the year to break Tim Flock’s single-season record. He kept winning into October, capturing his 10th race in a row at the Wilkes 400. Richard finished the year with 27 victories in 48 starts—17 of those wins coming in his final 24 starts. He copped the driving championship by more than 6,000 points.

Richard’s remarkable season may be difficult for modern racing fans to put into perspective. Perhaps the best way to understand it is to look past the track. During Richard’s amazing streak, stock-car racing made national headlines. He did for NASCAR what the Boston Celtics did for the NBA. In the South in particular, racing became front-page news. When Richard lost a race in Tennessee, and the next day}s headline trumpeted, “Petty Finishes Second.” With a national election looming on the horizon, Petty for President bumper stickers were an increasingly familiar sight. North of the Mason-Dixon Line, meanwhile, Richard Petty was the subject of articles in Newsweek, Sports Illustrated, Life and True.

Bill France knew a great public relations opportunity when he saw one, and he simultaneously promoted and protected Richard as he racked up win after win. When a couple of NASCAR beat writers questioned whether Richard was worthy of his new nickname, The King, France went public and proclaimed that he knew of “no other driver in NASCAR history who had brought more recognition to the sport.”

The wins came a little bit harder for Richard in 1968, mostly because of Pearson. Each driver won 16 races, but Pearson was more consistent. In the final months, Pearson battled Bobby Isaac for the NASCAR crown, with Pearson edging him in the fall. Richard finished third. His victories were primarily on short tracks. He won the Hillsborough 150 to close the Orange Speedway, one of NASCAR’s great old dirt tracks.

The most significant event of the 1968 season actually came in a race that Richard lost. He was leading the Islip 300 on Long Island when he attempted to lap Bobby Allison. Allison blocked him, crumpling Richard’s front fender with his rear bumper. The move cost Richard the race and, to make matters worse, Allison went on to win. Afterwards Maurice and cousin Dale Inman went after Allison, who at the time had fewer than a dozen wins under his belt. Richard, who was the same age, had more than 80.

Little did anyone realize that Allison would soon have more than 80 himself. Or that a great rivalry was brewing. Both drivers were loved by fans, so when they started rubbing fenders early in a race, the crowd was on the edge of its seat the rest of the way. The Petty–Allison “feud” helped fuel the sport’s popularity in the early 1970s.

The 1969 brought four new superspeedways on line—Michigan International Speedway, Dover Downs, Texas International Speedway, and Alabama International Motor Speedway in Talladega. Talladega was so fast that many top drivers—led by Richard—boycotted the September event there. His concern was based on the fact that the tire companies could not guarantee that their products could handle the high banks and 200 mph speeds.

NASCAR’s new fast tracks had prompted Richard to ask Chrysler to switch him to the more aerodynamic Dodge. He had won just one superspeedway race in his Plymouth Roadrunner the year before. Chrysler said no. The company wanted to keep the Petty name tied to the Plymouth nameplate.

Richard shocked the auto industry when he walked away from Chrysler and started driving Fords. In his first race in a Torino, he won at Riverside. He christened Dover Downs in one of history’s most dominant performances, winning by six laps. By season’s end, he had nine victories, including his 100th, achieved at Bowman Gray Stadium in Winston-Salem.

Richard finished a close second to Pearson in the standings. Earlier in the year, he had hit the wall at Asheville-Weaverville Speedway. Of all the crashes he had during his career, he rated this one “the worst lick I ever took.” He sat out two races, which would ultimately cost him a shot at a third championship.

Chrysler wanted Richard back in the worst way, and the company knew the way to get him was to design the slickest car NASCAR fans had ever seen. That car was the Plymouth Superbird, a sleek racer with a big airfoil on the back. To qualify it as a stock car, the company had to produce at least 1,500 for sale to consumers. It was a small price to pay for the services of The King.

The Superbirds were the talk of racing early in the year. At the Daytona 500, Pete Hamilton, driving for Petty Enterprises, passed Pearson in the final stages to win. Richard’s Superbird, meanwhile, was the talk of television. ABC Sports signed a deal to televise a handful of events in 1970, and Richard was either leading the field or crashing with millions tuned in. His wreck at the Rebel 400 in Darlington had NASCAR officials holding their breath. His car flipped four times and came to rest upside down. When Richard left the track, he was still unconscious. Fortunately, the worst of it was a separated shoulder, even though his head had hit the track several times. That aspect of the crash spurred NASCAR into mandating driver-side window netting.

Richard stepped out of his Superbird and into a Plymouth owned by Don Robertson for the final dirt track race in Grand National history. He took the checkered flag at the Raleigh State Fairgrounds in the Home State 200.

Richard was one of seven drivers vying for the NASCAR championship during 1970. He led everyone with 18 victories, but the five races he missed after his Darlington accident opened the door for Allison, Hylton and Isaac, who won the championship.

Richard would finally get his third driving title in 1971. By this time, it was called the Winston Cup, as R.J. Reynolds had signed on as NASCAR’s chief sponsor. The support could not have come at a better time—Ford and Chrysler had begun backing away from team sponsorship. At the Daytona 500, for instance, the Petty Enterprises team was the only one with factory support. Richard, in a Plymouth Roadrunner, and Buddy Baker, in a Dodge, worked their way to the front of the pack and challenged favorite A.J. Foyt, who looked golden until his car started sputtering on lap 161. He was out of gas.

The final 39 laps came down to a duel between the two Petty drivers. During his final pit stop, Baker ordered his crew to loosen up his chassis. They did so but protested the move. As soon as he hit the track, Baker knew it was a mistake, his back end was sliding all over the place. Richard won by 20 seconds. No other driver had taken the checkered flag at Daytona more than once. Richard had now won it three times.

It was one of 21 victories in a spectacular year for Richard. Allison, with 11 wins, was the only driver who came close to him. Richard started 46 races and finished in the Top 5 a remarkable 38 times. He earned $351,000 in prize money—the first driver ever to eclipse the $300K mark. He also surpassed $1 million in career earnings. Richard topped off his year by driving his car onto the White House lawn, where he was congratulated by President Richard Nixon.

The 1972 Winston Cup title was a three-way race between Richard, Allison and Hylton. The Petty team went into battle with a deep-pocketed sponsor, STP. Big changes made the NASCAR standings work differently than in past years. The schedule was cut to 30 events, and no race was shorter than 250 miles. Also, points would be awarded for total laps, so crashes were particularly costly.

During the year the Petty-Allison rivalry reached its zenith. At the Capital City 500 in Richmond, the two drivers traded paint until Richard’s car climbed the guardrail. Somehow he regained control and got it back on the track—and won the race! Three weeks later, the pair was at it again in the Wilkes 400, bumping and grinding through the final laps. Richard edged Allison, but both cars looked like they’d been in a demolition derby. In Victory Lane, a drunken fan took a swing at Richard. Maurice grabbed his brother’s helmet and clocked the fan over the head.

Allison ended up setting a NASCAR record during the 1972 season by leading in his 39th consecutive race, but it was Richard who got the hardware at season’s end. His third-place finish at the Texas 500 gave him a 128-point victory over his rival.

Richard started the 1973 campaign with his fourth Daytona 500 victory. It was a battle of Dodges, as pole-winner Buddy Baker led most of the race. With 12 laps to go, Richard’s crew turned out an 8.6-second pit stop to vault him into the lead. Baker, in the faster car, screamed through the pack in pursuit but blew his engine with six laps to go. Richard streaked across the finish line in a car sporting his new red-and-blue color scheme.

Back at Daytona in July for the Firecracker 400, Richard and Pearson dominated the race, lapping the field four times. In a thrilling duel to the finish, Pearson earned the checkered flag. Although the Petty-Allison feud was still fun, fans were beginning to pay more attention to the rivalry between Pearson and Petty. Both had earned their spurs on the short tracks, and both proved to be cagey winners on the superspeedways. In 1973, Pearson won more races than Richard—11 to 6—but Richard finished well ahead of him in the standings. Be that as it may, Richard finished fifth overall. The season came down to the last race, with five drivers having a mathematical shot at the Winston Cup. In the end it was Benny Parsons—a former cab driver—who was crowned king of NASCAR.

Richard repeated as Daytona 500 champ in 1974. The race was reduced to 450 miles as a public relations move by NASCAR in the midst of the energy crisis. The race developed into a two-man duel between Richard and Davey Allison, Bobby’s brother. It looked like as Allison win when Richard cut a tire on lap 181, but he maintained control, dipped down into the pit, and got back on the track with 37 seconds to make up. This he did thanks to a blown tire and bungled pit stop for Allison.

That August, NASCAR christened Pocono International Raceway, and Richard cruised to victory in the Purolator 500. Later in the month, he edged Pearson to win the Talladega 500. Richard won 10 races in all and easily outpointed the field for the Winston Cup title. Actually, thanks to a weird rule change by NASCAR, Richard got bonus points for his Daytona win after each race, so there was almost no way to catch him. For example, at the Southern 500, he crashed and finished in 35th place. Young Darrell Waltrip, who finished second, got less points that day than Richard did! In 1975, the problem was corrected—perhaps too far the other way. Now each race would carry exactly the same weight in the standings.

Richard made the new scoring system academic when he won 13 of NASCAR’s 30 events. Among his victories were the World 600, National 500 and Delaware 500. Although Petty Enterprises was ecstatic over their second straight Winston Cup championship, the season was also tinged with despair. At the Winston 500, Richard pulled into the pits when a wheel bearing caught on fire. His 20-year-old brother in law, Randy Owens, a member of the pit crew, tried to put out the flames with a pressurized water hose. The tank exploded, killing Owens instantly.

The 1976 season featured a Daytona 500 finish that fans still talk about. After 450 miles, Richard and David Pearson had made the race a two-man affair. Pearson rode Richard’s tail until the last lap, hoping to slingshot past him. This he did on the backstretch, but he entered the third turn too high, allowing Richard to pass him low. They were side-by-side in the last turn when they bumped, sending Pearson into the wall. He bounced into Richard’s rear bumper, and both cars went spinning out of control.

Richard’s car came to rest 100 feet from the finish line, but his engine had stalled. Pearson had the presence of mind to engage his clutch when he was pinballing around the track, which kept his car alive, albeit it in first gear. He chugged past Petty at 20 mph and crossed the finish line to win.

Richard won three races during the 1976 season and held the points lead as late as September, setting the pace in a three-way battle with Cale Yarborough and Benny Parsons. Yarborough regained the lead and pulled away on the strength of nine victories, edging Richard by fewer than 200 points.

Richard finished second to Yarborough again in 1977. He led the Winston Cup points battle in July, but Yarborough ran an amazingly consistent season, finishing every one of his 30 starts. Richard won five times, including the Firecracker 400 at Daytona. It marked the 18th consecutive season that he had won at least two races—a mark that is unlikely to be equaled anytime soon.

The streak came to an end in 1978, when Richard went winless for the first time since his rookie season, in 1959. He competed for several months in a Dodge Magnum without any luck. He switched to a more powerful Chevrolet but still couldn't win. He came close at the Dixie 500 when the crowd thought he had nosed out Dave Marcis at the finish line. What they—and NASCAR officials—had failed to notice was that Donnie Allison had passed them both several laps earlier.

Richard still placed sixth in the Winston Cup standings, finishing more than half his races among the Top 10. Yarborough, with another magnificent season, won his third straight driving championship,

Richard’s winless streak had reached 45 events when the 1979 Daytona 500 began. He was a mile behind leaders Yarborough and Donnie Allison when they crashed in Turn 3 and began swinging at each other in the infield. Richard could hardly believe his luck. He darted through the debris for an unexpected victory—his sixth in NASCAR’s biggest race. The end of the race was broadcast live by CBS and drew big ratings. American sports fans got to see what many consider to be the wildest-ever finish to a major sports event. It was a watershed day for stock-car racing.

Following Richard across the finish line was Darrell Waltrip. They would finish 1–2 again at Darlington in April, with Waltrip winning this time. Few races during the 1970s featured a more exciting finish. The two drivers traded the lead four times in the four laps prior to the final go-round. On the last lap, there were three more passes. Richard had the lead coming out of Turn 3, but Waltrip regained in Turn 4 and won the race by a car length.

The victory helped Waltrip build a comfortable lead in the points standings. With seven races to go, Richard trailed by nearly 200 points. He made a furious comeback and trailed by just two points when the last race of the season began, in Ontario, California. Both cars were running well, but Waltrip got trapped behind a big spinout and lost a lap. Richard finished fifth—six spots ahead of Waltrip—to win his seventh driving championship by a mere 11 points.

There was more reason to celebrate the 1979 season. Richard’s son, Kyle, made his first Winston Cup start. Driving a red-and-blue Dodge Magnum like his dad—and taking his grandfather’s old #42—he made his debut at the Talladega 500 in August and finished ninth.

Richard’s 1979 championship turned out to be his last. During the 1980s, a new generation of stars in their many years his junior were seizing the initiative in NASCAR. Richard, in his 40s, would finish among the Top 10 each year from 1980 to 1984, and again in 1987. In 1986, Kyle finished ahead of his father for the first time.

That is not to say that Richard wasn’t competitive. On the contrary, for most of the decade he was a threat to win any race he entered. In 1980, he was right behind young Dale Earnhardt in the standings when he broke his neck in a crash at Pocono. Richard hid the injury from NASCAR but fell off the pace and finished fourth, with two victories.

In 1981, Richard captured his seventh Daytona 500. NASCAR had downsized its wheelbase to reflect America's move to smaller automobiles, but at 190 mph the handling of the new models was dicey. As a result, the 500 featured a lot of passing, but not much side-by-side racing—and only four caution flags. Bobby Allison led the race and looked like a good bet to win until he ran out of gas. New leaders Earnhardt and Buddy Baker refueled and changed tires. Richard also pitted, waved off the tire change and blew out of the pits with a slim lead. He won the race by 3.5 seconds over Allison. In Victory Lane, Richard hoisted his seven-month-old grandson, Adam, to a roaring crowd.

The Petty Enterprises team had used every bit of luck, guile and brainpower to win the Daytona 500. But they would have to go forward in 1981 without an important member of the team, cousin Dale Inman, who left to work with Earnhardt. Richard won two more races that year to finish eighth in the standings.

Richard went winless in 1982, but he finished fifth in points on the strength of nine Top 5 outings. Among his notable near-misses was thrilling finish at the Champion 400 in Michigan. At the Firecracker 400, rookie Geoff Bodine slammed into Richard as he maneuvered carefully through a wreck. The following week his car sported a bumper sticker that read: “Save the South—Teach a Yankee how to Drive.”

It was a difficult year for the Petty team, which struggled to keep two cars in tip-top shape. During the summer, Kyle left the team to drive for owner Hoss Ellington. He returned to the family business in the fall.

Richard ended a 43-race winless streak in March of 1983 with a bumper-length win over Bill Elliott at the Southern 500. Two months later, he outraced Lake Speed and Benny Parsons to the checkered flag at Talladega in the Winston 500. Richard’s third win of the season—and 198th of his career—came amidst controversy at the Miller High Life 500 in Charlotte. After the race, NASCAR inspectors nailed him for two infractions, mounting left-side tires on the right side and an engine that was too big. Richard was docked 104 points and fined a NASCAR-record $35,000 for these transgressions, but he was allowed to keep the victory. It’s good to be The King.

Richard finished the year in fourth place. His old nemesis, Bobby Allison, took the title. After the season, Richard announced that he would no longer be racing for Petty Enterprises. In 1984, he hooked up with owner Mike Curb and enjoyed an exciting and successful season. In early May, he was one of 13 drivers involved in a record 75 lead changes at the Winston 500, ultimately finishing in back of winner Cale Yarborough. Later that month, Richard drove to victory in the Budweiser 500 at Dover. He beat Tim Richmond by four seconds for his 199th career victory.

Number 200 came on July 4th at the Firecracker 400. President Ronald Reagan was in the broadcast booth as Richard and Yarborough battled for the lead in the final few laps of the race. When Doug Heveron spun out the yellow flag emerged, both veteran drivers knew what that meant—the race would end under caution, so the first to reach the flag would win. Richard beat Yarborough to the line by inches. The win helped Richard finish in the Top 10 that season.

In the garage afterwards, Richard and the President dove into a bucket of Kentucky Fried Chicken. “I won my race,” he told Reagan, who was running for a second term. “now you go win yours.”

The Firecracker victory would be Richard’s last. He finished 14th in the standings in 1985 and 1986, 8th in 1987, and 22nd in 1988. The 1988 season saw Richard’s most spectacular crash. On the 106th lap of the Daytona 500, he bumped fenders with Phil Bakdall and then went airborne after A.J. Foyt hit him. After tumbling several hundred yards, Richard was hit again, by Brett Bodine. His car disintegrated, showering the crowd with engine parts. Incredibly, Richard was shaken up but for the most part uninjured.

Richard and Kyle finished 29th and 30th in 1989, but it was a dismal season for the senior Petty. In 25 starts, he failed to notch even one Top 10 finish. His luck hardly improved in 1990, when he managed one Top 10 finish in 29 starts. He put up identical numbers in 1991, finishing 24th in the standings.

Richard’s final Winston Cup season was 1992. He enjoyed a bit of glory at the Firecracker 400 in July, qualifying on the front row of a race for the first time since 1986. President George Bush was in attendance, and he cheered with the rest of the crowd as Richard zoomed out in front for the first five laps. The heat of the day was overwhelming, however, and he had to stop midway through the race.

Richard made 29 starts in all in 1992, his final one coming on November 15 at the Hooters 500 in Atlanta. The day would go down in history, not just for Richard’s farewell to racing, but as the Winston Cup debut of Jeff Gordon. It was a true passing of the torch. Richard finished his 35th year of Grand National competition ranked 29th. He was 56 years old. Having decided that 1992 would be his final year as a driver, Richard participated in farewell ceremonies at each track, leading the pack for the pace lap at every race.

As the most recognizable celebrity in his sport, Richard stayed busy in his post-driving years. He did some TV commentary, opened a museum and driving school, and ran his own team. He won four races in the 1990s with Bobby Hamilton and John Andretti at the wheel. He also gave crew chief Robbie Loomis his start. After a decade, Richard relinguished day-to-day ownership duties to Kyle, and eventually Petty Enterprises was sold to Ray Evernham’s group. In 1996, he ran for North Carolina Secretary of State but was narrowly defeated.

As a personality, Richard continued to be in demand. He has promoted more than a dozen products and brands over the years, from Goody’s Headache Powder to GlaxoSmithCline to his own cereal and footwear line. In the Pixar film Cars, he played himself as the #43 Superbird.

The racing gene that passed from Lee to Richard to Kyle turned out to be especially strong in Kyle’s son, Adam. Richard and Adam shared a close relationship based on their intense passion for racing. During one of Adam’s first races, his crew chief, Chris Bradley, was killed during a pit stop when he tried to adjust a swaybar without alerting the jack man what he was doing. Adam was devastated. When he came home, Richard shared his own story about death in the pits and helped Adam work through his anguish.

Adam joined the Winston Cup circuit in 2000 at the age of 19. He and Kyle qualified for the DirecTV 500 at the Texas Motor Speedway. Richard was unable to attend because his own father was losing his battle with a stomach disorder at the age of 86. Lee passed away a few days later.

Adam’s next start was a Busch Series event in Loudon, New Hampshire. During practice, his accelerator stuck heading into a curve at 150 mph, and he was unable to kill the engine and steer out of danger. His body was destroyed when he hit the wall. Richard tried to make sense of the tragedy. Many of his friends had died the same way. Like them, maybe it was just Adam’s time, he thought.

In October of 2009, Richard was one of five members of the NASCAR Hall of Fame’s inaugural inductee class. He will be enshrined in May of 2010 along with Bill France Jr. and Sr. and fellow drivers Junior Johnson and Dale Earnhardt, the only man to match Richard’s record of seven career NASCAR championships.

It is debatable whether any athlete in any sport deserves the title of “King.” But who can honestly begrudge this honor to Richard Petty? He established records for success that are unlikely to be broken—including 200 career victories, 27 wins in a season, and seven checkered flags at Daytona—and records for consistency—including 513 consecutive starts, 712 Top 10 finishes, and 127 poles won—that boggle the mind.

Richrd’s popularity among NASCAR fans is unmatched as well. His name is synonymous with the sport. He is a legend in his own time, celebrated for his amazing record on the track and revered for everything he stands for. The King is a moniker that suits him perfectly.