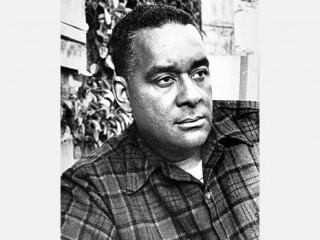

Richard Wright biography

Date of birth : 1908-09-04

Date of death : 1960-11-28

Birthplace : Natchez, Mississippi, United States

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2010-10-01

Credited as : Writer and lecturer, The Voodoo of Hell's Half Acre, autobiography Black Boy, 1945

0 votes so far

Writings

* Uncle Tom's Children: Four Novellas, Harper & Brothers, 1938.

* Native Son, Harper & Brothers, 1940.

* Twelve Million Black Voices: A Folk History of the Negro in the United States, Viking, 1941.

* Black Boy: A Record of Childhood and Youth, Harper & Brothers, 1945.

* The Outsider, 1953.

* Black Power, Harper & Brothers, 1954.

* Savage Holiday, Avon, 1954.

* The Color Curtain, World, 1956.

* Pagan Spain, Harper & Brothers, 1957.

* White Man Listen, Doubleday, 1957.

* Long Dream, Doubleday, 1958.

* Eight Men, World, 1961.

* Lawd Today, Walker, 1963.

* (Contributor) The God That Failed, edited by Richard Crossman, Books for Libraries Series, 1972.

* American Hunger, Harper & Row, 1977.

Published first story, "The Voodoo of Hell's Half Acre," 1924; worked variously as a dishwasher, busboy, porter, street sweeper, and group leader for a Chicago Boys Club; worked for U.S. Postal Service, Chicago, beginning in 1932; wrote poetry for leftist publications; attended American Writers' Congress, New York City, 1935; prepared guidebooks for Federal Writer's Project, mid-1930s; worked for Federal Theater Project, 1936; wrote for the Daily Worker, late 1930s; published Uncle Tom's Children, 1938; published Native Son, 1940; published autobiography Black Boy, 1945; lectured, appeared on radio and television, and contributed to periodicals, late 1940s; attended Bandung Conference in Indonesia, 1955.

As a poor black child growing up in the Deep South, Richard Wright suffered poverty, hunger, racism, and violence--experiences that later became central themes of his work. Wright stands as a major literary figure of the 1930s and '40s, his writings a departure from those of the Harlem Renaissance school. Steeped in the literary naturalism of the Depression era, Wright's work expresses a realistic and brutal portrayal of white society's oppression of African Americans. Anger and protest served as a catalyst for literature intended to promote social change by exposing the injustices of racism, economic exploitation, and imperialism. Through his art, Wright turned the torment of alienation into a voice calling for human solidarity and racial advancement.

Wright was born on September 4, 1908, in the backwoods of Mississippi, on a plantation 25 miles north of Natchez, to a farmer and a schoolteacher. Descended from a family lineage of black, white, and Choctaw Indian, he spent the early years of his life playing among the "moss-clad" oaks along the Mississippi River. After failing to make a profit on his rented farm, Wright's father decided to move the family to Memphis, Tennessee. Upon arrival by paddleboat steamer in 1911, the Wrights took residence in a two-room tenement not far from Beale Street. To Wright, the concrete pavement appeared hostile and dreary compared to the pastoral serenity of his former home. In a city filled with brothels, saloons, and storefront churches, Wright encountered the terrors of violence, vice, and racism.

The increasing absence of his father fueled Wright's growing sense of anger and estrangement. By the time the boy was six years old, his father had deserted the family to live with another woman. At first, he was elated to be free from his father's abusive behavior, but he soon realized that this newfound freedom brought severe poverty. "The image of my father became associated with the pangs of hunger," wrote Wright in his autobiography Black Boy. "Whenever I felt hunger, I thought of him with a deep biological bitterness." Left with two children to support, Wright's mother went to work as a housemaid and cook. After a brief period in an orphanage around 1915, Wright attended school for a short time at Howard Institute. "This period in Memphis was the beginning of adult suffering," wrote poet Margaret Walker in her book Richard Wright, Daemonic Genius, "the beginning of a terrible rage that he himself did not always understand."

Around 1919 the failing health of Wright's mother forced her to take the children to live with relatives in Arkansas. A year later, the Wrights moved to Richard's devoutly religious grandparents' home in Jackson, Mississippi. The household was dominated by Wright's grandmother and Aunt Addie, both of whom were Seventh-Day Adventists. Because of his rebellious attitude toward evangelical teachings, Wright lived as an outsider within the family. Although nonreligious literature was forbidden, he managed to acquire pulp magazines, newspapers, and detective stories. Inspired by local folklore, country sermons, and popular literature, Wright's first story "The Voodoo of Hell's Half Acre," was published in 1924 by a local black newspaper. Undaunted by the family's criticism of his work, Wright aspired to become a writer.

To pursue this dream, Wright shifted his attention northward, to a place where he could escape the hostility of southern rural evangelical culture. With only a ninth-grade education and little money in his pocket, Wright fled to Memphis at the age of 17. There he became acquainted with the work of H. L. Mencken. In the fiery prose of Mencken, Wright learned that words could serve as weapons with which to lash out at the world. Soon afterward, Wright discovered such naturalist writers as Theodore Dreiser, Sherwood Anderson, and Sinclair Lewis. As Arnold Rampersad stated in the introduction to Wright's Lawd Today, the author's avid study of serious literature in Memphis became "the most effective counter to both his profound sense of isolation and the dismal education he received as a boy in Mississippi."

Unfortunately, Wright did not find the atmosphere of Memphis as enlightening as his private studies. Violence and hatred perpetrated by whites reinforced his dim view of the South. In November of 1927, Wright boarded a train bound for Chicago. His departure symbolized the end of a stay in an alien land where he existed as a "non-man" within the chasm of the black and white worlds.

Wright's family soon joined him in Chicago. Together they lived in a cramped apartment on the city's South Side. Bored with his studies, Wright left high school to help support the family. He took a number of odd jobs, working as a dishwasher, porter, busboy, street sweeper, and group leader at a South Side Boys Club. In 1932 Wright worked as a clerk at the Chicago post office. Nicknamed "the University," the post office employed numerous radical intellectuals, some of whom invited Wright to attend the meetings of the John Reed Club, a revolutionary writers' organization. While exposing him to Communist literature and Marxist ideology, club members encouraged Wright to pursue a professional writing career. Inspired by their support and enthusiasm, Wright began to write poetry for various left-wing publications.

Around this time, Wright's interest in race relations and radical thought led him to join the Communist party. Within the Communist ranks, he found, for the first time, a formidable peer group sharing a common goal of promoting racial and social equality. "It seemed to me that here at last, in the realm of revolutionary expression," Wright stated in his contribution to the book The God That Failed, "Negro experience could find a home, a functioning value and role." For a brief period, Wright's sense of loneliness subsided. Communism appeared to offer an alternative that could not only quell his own inner conflict, but the threat of poverty and racism confronting the disinherited peoples of all nations.

In 1935, after the Communist party disbanded the John Reed Clubs, Wright hitchhiked to New York, where, along with prominent writers like Langston Hughes, Malcolm Cowley, and Dreiser, he attended the American Writers' Congress. Back in Chicago that year, he found employment preparing guidebooks for the Federal Writer's Project, a New Deal relief program for unemployed writers. Early in 1936, Wright was transferred for a short time to the Federal Theater Project. Wright also wrote for the Daily Worker and started work on a collection of short stories and a novel, posthumously published as Lawd Today in 1963.

Wright's burgeoning literary career, however, soon conflicted with his membership in the Communist party. In Chicago, his study of sociology, psychology, philosophy, and literature led him to question the rigid policies of Stalinism and the aesthetic aspects of socialist realism. He found that recruiting, organizing, and distributing party literature interfered with his writing assignments. Moreover, the expulsion of many fellow members and the constant questioning concerning his loyalty alerted Wright to the duplicitous and paranoid nature of the organization. Accused of betraying the party by several Chicago Communists in 1937, Wright--tired of the Chicago scene--decided to leave for New York.

Not long after arriving in New York City, Wright won a Works Progress Administration award for his collection of novellas, published as Uncle Tom's Children in 1938. Based on Wright's Mississippi boyhood, "these stories were almost unbearable evocations of cruel realities," explained poet Arna Bontemps in Anger and Beyond. "His purpose was to force open closed eyes, to compel America to look at what it had done to the black peasantry in which he was born."

For the better part of a year, Wright took time off from his jobs at the Writer's Project and the Daily Worker to work on a novel. Published in 1940, Native Son became a Book-of-the-Month Club selection, selling over a quarter of a million copies in six months. By far Wright's most famous and financially successful book, Native Son is a militant racial manifesto exposing the evils of racism and the capitalist oppression of blacks in urban society. Based on the actual criminal case of convicted killer Robert Nixon, the book describes the story of Bigger Thomas, a street-hardened black youth who murders the daughter of a well-to-do white family while working as their chauffeur. Hunted down by white society, Bigger is sentenced to death by the very power structure responsible for his alienation, subjugation, and ultimate impulse to commit murder.

In 1941, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People awarded Wright the Spingarn Medal for Native Son. Another great honor was bestowed on Wright when actor-producers John Houseman and Orson Welles mounted a stage adaption of Native Son, featuring the outstanding actor Canada Lee in the role of Bigger. Also in 1941, Wright published his third book, Twelve Million Black Voices, a folk history featuring photographs by Edwin Rosskam. Following his formal break with the Communist party in 1944, Wright wrote an essay for the Atlantic Monthly entitled "I Tried to Be a Communist," explaining his reasons for leaving the party. Wright's finest work of the decade, however, was his autobiography Black Boy. Published in 1945, Black Boy is a harrowing record of Wright's early years in the South. In a review in the Nation, noted literary scholar Lionel Trilling described Black Boy as a "remarkable book" of great "distinction" and "purpose." Social scientists and historians continue to study the book's impact on black and white society long after its publication.

Encouraged by avant-garde writer Gertrude Stein, Wright expressed an interest in visiting France. In the spring of 1946, he embarked for Paris on an ocean steamer. The city's colorful streets and cultured citizenry greatly impressed Wright. Stein introduced him to a number of leading French intellectuals, including Claude Magny and Maurice Nadeau. Wright went back to New York in January of 1947. He intended to resume work there, but rampant racism and the anti-radicalism of the Cold War era made him restless to return to France. In May of 1948, Wright moved into an apartment on Paris's Left Bank.

In permanent exile in Paris, Wright enjoyed celebrity status. He spent a great deal of time lecturing throughout Europe and appearing on radio and television. Besides his close association with existentialist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre and the members of the Les Temps Modernes group, Wright became an active member of the Pan-African organization Presence Africaine. His 1953 novel, The Outsider, exemplifies the increasing influence of existentialism on his work. Black Power, completed following his trip to Ghana in 1954, presents a Pan-African perspective. After attending a 29-nation gathering of representatives of African and Asian countries at the Bandung Conference in Indonesia, Wright wrote The Color Curtain, which appeared in 1956. A year later, he produced a travelogue, Pagan Spain, based on his observations of Spanish culture, politics, and religion. Up until his death from a heart attack in Paris in 1960, Wright continued to work on several literary projects, including a collection of short stories, Eight Men, published posthumously in 1961.

From the depths of the Mississippi Delta to the cities of Europe, Africa, and Asia, Richard Wright emerged an international literary figure championing the cause of social and racial justice. Poet, writer, social critic, and journalist, Wright authored about a dozen books and numerous poems and essays, most of which address the evils of racism and man's inhumanity to man. "Wright's unrelentingly bleak language was not merely of the Deep South or Chicago," commented writer James Baldwin in an essay titled "Alas Poor Richard," "but that of the human heart." It was Wright's destiny, as he himself wrote in The God That Failed, "to hurl words into the darkness and wait for an echo ... no matter how faintly." Decades after his death, Wright's words still reverberate across the world--their dark and ominous tone embodying a message of hope for all humanity.