Rick Barry biography

Date of birth : 1944-03-28

Date of death : -

Birthplace : New Jersey, USA

Nationality : American

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2010-08-04

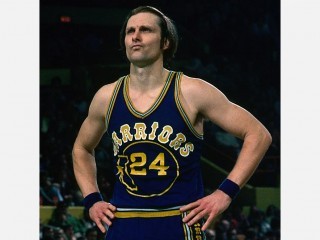

Credited as : Basketball player NBA, played for Houston Rockets , and Golden State Warriors

0 votes so far

Richard Francis Dennis Barry III was born on March 28, 1944, in Elizabeth, New Jersey. His father, Richard Barry Jr., played on local semipro clubs and also coached at the St. Peter and Paul parochial school. Rick and his older brother (by four years), Dennis, learned the game from their dad, who hammered the fundamentals into them from an early age. The teaching continued at the dinner table, much to Mrs. Barrys chagrin. She had only a passing interest in the sport.

In fifth grade, Rick made the school team. Most of the other boys were of junior high school age, but he was as tall and quick and talented as any of them. Having tagged along with Dennis all those years gave him valuable experience against older players. Ricks father was a strict coach, especially with his own son. He sometimes pulled Rick for making a single mistake.

When Rick was ready for high school, the Barrys moved a few towns west on Rte. 28 to Roselle Park, where he made the Roselle Park High School varsity. Though he had the ball-handling skills and court vision of a guard, he played forward for the team. Rick participated in a number of other sports, from baseball to tetherball, and was always the best at whatever he tried. The only thing that seemed to hold him back was his temper. Trained to see ahead in ways his opponents, teammates and even coaches could not, Rick was easily frustrated when he felt others were impeding his progress. It would take him several years to bring this part of his personality under control.

Rick, meanwhile, was developing into an unstoppable force on the hardwood. His first basketball coach was his dad, who schooled him in the fundamentals of the game. At Roselle Park High School, Rick was voted All-State twice. By then he stood more than six feet tall, and though he looked skinny in his uniform, he dominated opponents with a physical style of play. Rick could hit his jump shot from anywhere on the floor, but he was at his best taking the ball hard to the hole. His take-no-prisoners attitude resulted in bumps, bruises and regular trips to the foul line.

In the fall of 1961, Rick headed south for the University of Miami. From a basketball standpoint, it was an interesting decision. The Hurricanes were hardly a powerhouse, but coach Bruce Halewhose nickname was Slickwas a good recruiter who helped convince Rick that Miami was the place for him. A one-time NBA star and former referee, Hale took over the program in 1954, then transformed the Canes from a perennial doormat into a giant killer. He brought in the school's first All-American (Dick Hickox) and seven-footer (Mike McCoy). Hale also earned Miami national recognition. In 1960, the year before Rick showed up, the Hurricanes rose to #10 in the country. With a mobile forward like Rick on the team, Hale saw the chance to compete at college basketball's highest level.

After a season on the freshman squad, Rick moved right into the starting lineup and soon blossomed into Miami's best player, averaging almost 20 points and 15 rebounds a game. Miami was all that he expectedgood basketball and great weatherexcept for the facilities. The school didn't have a field house or gym. The Hurricanes played their home games at the Miami Beach Convention Hall (or the Auditorium next door). Practices were held at the campus armory, which the team shared with the U.S. Army. But no one, including Rick, ever complained.

Hale was something of a legend back then. He was one of a handful of top-level stars (including George Mikan, Bob Davies and Arnie Risen) who came over from the National Basketball League in the post-war years and enabled the Basketball Association of America to survive its embryonic years, and eventually evolve into the NBA. As a coach, Hale was ahead of his time. He treated his players like human beings, inviting them for cookouts at his home, letting them swim in his pool, and running with them in scrimmages. Rick also loved Hale because he gave him so much freedom to explore his game.

In his final two seasons at Miami, Rick established himself as one of the nation's premier players. He nearly doubled his scoring from his sophomore campaign to his junior campaign, then led the country at 37.4 ppg as a senior. During that time Miami was one of the most exciting teams in the nation. With guards like Bernie "Boom Boom" Betts, Junior Gee, Rick Jones and John Dampier complementing Ricks superb all-around skills, the Hurricanes often ran opponents out of the building.

When Rick graduated in 1965, he expected to go high in the NBA draft. Pro teams didn't necessarily agree. Though he averaged 29.8 points and 16.5 rebounds during his 77-game career for the Hurricanes, Rick also displayed a white-hot competitive fire that sometimes got him in trouble. As a junior he almost came to blows with a San Francisco player for a wild elbow thrown in his direction. A year later he broke the jaw of a Loyola player with one punch. Ricks intensity scared off some NBA executives, who feared he might be too hot-headed to become a top pro. Others wondered whether he could handle the pounding of the pro game. Knicks president Ned Irish and Detroit assistant Earl Lloyd were among those dubious of Ricks ability to cut it at the next level.

Rick hoped to be selected by New York as a territorial pick, but the Knicks took Princeton star Bill Bradley instead (this was the last year the NBA allowed teams this privilege). Michigans Bill Buntin was claimed by the Pistons, and the Lakers grabbed UCLA guard Gail Goodrich. After the territorial choices, the San Francisco Warriors owned the first and second picks in the first round, with the Knicks choosing third. The Warriors took Fred Hetzel of Davidson, then Rick. Among those taken after the Miami product that spring were Billy Cunningham, Jerry Sloan, Bob Love and the Van Arsdale twins.

Rick was eager to prove his critics wrong. In 1965, he joined a Warrior club trying to find its identity after the trade of Wilt Chamberlain to the Philadelphia 76ers. The teams record in 1964-65 had been 17-63, by far the leagues worst mark. Working with point guard Guy Rodgers, Rick injected new life into the club. In his first season, he surpassed Elgin Baylors rookie record for points with 2,059, and finished second in the league in free-throw percentage (.862) and 10th in rebounding (10.6 rpg). Rick was named Rookie of the Year and All-NBA First Team.

Indeed, Rick was even better his second season with San Francisco. Playing for new coach Bill Sharman, he topped the NBA at just over 35 points a game, breaking Chamberlain's seven-year stranglehold on the scoring title. After taking home honors as the All-Star Game MVP, Rick was voted All-NBA First Team for the second year in a row. His fine play boosted the Warriors to 44 wins and the division title. After sweeping the Lakers and beating the Hawks in six games, San Francisco met Chamberlain and the 76ers in the NBA Finals. In a high-scoring series, the Warriors lost in six games. Rick set a new championship mark with a 40.8 scoring average (which stood until Michael Jordan erased his name from the record books in 1993), including one game when he hit for 55.

After the 1967 NBA Finals, Rick was courted by the fledgling American Basketball Association, which was placing a team in the Bay Area. The Oakland Oaks had hired Bruce Hale (Ricks father-in-law since 1965) to coach the club, and were dangling a $75,000 contract and a cut of ownership if Rick agreed to jump leagues. The All-Star told the Warriors and their owner, Franklin Mieuli, to give him their best offerhe would have stayed had it been close to the Oaks deal. But it wasnt, so Rick became the first major NBA star to join the ABA.

Rick was skewered by the press for being selfish and disloyal, but he didnt necessarily want to leave the Warriors. The feeling was mutual. A heartbroken Mieuli hung jersey #24 in his office and vowed to get his star back some day.

There was a price to pay for leaving the NBA. The Warriors contested Ricks contract in court, and a judge ruled that he was bound to the team for the 1967-68 season. Either he played for San Francisco, or no one at all. Rick stuck to his guns, and spent the year doing TV work for the Oaks. He also suited up as the point guard for the KYA hoops team (the Radio Wonders), feeding the likes of Johnny Holliday (the play-by-play voice of the Maryland Terrapins for the past 20 years) and Steve Sommers (a popular overnight host on WFAN sports radio in New York). Without its star, Oakland stumbled to a 22-56 record, the worst in the league.

The following season, Alex Hannum took over for Hale and Rick became a one-man publicity campaign for the ABA as he led the Oaks to 15 wins in their first 17 games. Sixteen straight victories after that gave Oakland an insurmountable lead in the West, and the team cruised to the division title despite a knee injury that ended Ricks season. He still led the league in scoring and was named MVP, but he was not good to go come playoff time. Incredibly, the Oaks still captured the ABA championship. Prior to the season, the team had picked up starters Doug Moe and Larry Brown from the New Orleans Buccaneers, and rookie guard Warren Armstrong muscled his way into the first five. Gary Bradds, Henry Logan and Jim Eakins gave Hannum the leagues best bench. The Oaks survived a tough series with the Denver Rockets, swept the Bucs in the semifinals, then surprised the Indiana Pacers in a five-game final.

After the 1968-69 campaign, the Oaks, in dire financial straits, were purchased by Washington lawyer Earl Foreman. To save the struggling franchise, he planned to move the team to D.C. Rick, however, wanted nothing to do with the East Coast. With Mieuli desperate to bring his former star back to San Francisco, he signed Rick to a five-year contract worth $1 million. Now it was the ABA's turn to take the game from the basketball court to the court room.

Rick spent one season with the Washington Capitols, averaging 27.7 pointsthough his knee kept him out of two dozen games. Injury problems also felled Logan, Armstrong and George Carter, and the depleted Caps lost to Denver in the first round of the playoffs. Fan interest in the team was practically non-existent, so heading into the 1970-71 campaign, the team was uprooted once again. This time the club would play as the Virginia Squires and rotate between arenas in Richmond, Norfolk, Roanoke and Hampton. Rick decided enough was enough, and launched a campaign to get himself traded. The ABA, fearful their biggest star might return to the NBA, stepped in and brokered a deal between the Squires and the New York Nets.

Rick transformed the Nets into a championship contender. Point guard Bill Melchionni blossomed into the leagues top assist man, John Roche electrified fans with his fancy dribbling, and St. Johns star Billy Paultz became one of the leagues best centers. In the 1972 playoffs, the Nets upset the powerhouse Kentucky Colonels, then edged the Squires in seven games to reach the finalswhere they lost to an excellent Pacers club in six games. In two years with the Nets, Rick extended the range and accuracy of his jumper, his assist totals rose, and he further developed his defensive game.

After the 1971-72 campaign, Rick was compelled to change his address once again. A California judge ruled that he had to honor the contract he had signed with the Warriors three years earlier, so it was back to San Francisco (where the team was now known as Golden State).

After two years reacquainting himself with the NBA, Rick had a season for the ages in 1974-75. Expectations for the Warriors were low heading into the campaign, given that the team had cleaned house of veteran stars Nate Thurmond, Cazzie Russell, Clyde Lee and Jim Barnett. Guard Jeff Mullins, now in his 30s, was relegated to a supporting role. New to the team was center Clifford Ray and rookies Keith Wilkes and Phil Smith. Rick, named team captain by coach Al Attles, ran the show along with point guard Butch Beard. Attles utilized a deep roster of interchangeable parts, and guided the Warriors to a 48-34 record in the regular season. Rick pumped in 30 points and dished out six assists per game. In the playoffs, facing elimination in the Western Conference Finals against Chicago, Golden State fought back to take the series in seven games. That set up a showdown against the juggernaut Washington Bullets for the title. No one gave the Warriors the slightest chance of winning, but behind Rick's MVP performance, they ambushed Elvin Hayes & co. in four games.

Golden State was unable to defend its title the following year. After posting the league's best record, the Warriors were surprised by the Phoenix Suns in the Western Conference Semifinals. Though Rick's scoring average for the 1975-76 campaign dropped by nine points, he still earned his third straight nomination to the All-NBA First Team. Critics blamed him for the defeat to the Suns, however, claiming he had wilted under the pressure of the post-season.

After two more solid seasons with Golden State, Rick became a free agent. He signed with Houston, where he hoped to win another championship. The Rockets were loaded, with Moses Malone, Rudy Tomjanovich, John Lucas, Mike Newlin and Calvin Murphy. But Rick's experience in Houston was unfulfilling. The team lost in the first round of the playoffs in 1978-79, then lumbered through the following year and barely qualified for the post-season. After an opening-round upset of the San Antonio Spurs, the Rockets were sent home by Larry Bird and the Boston Celtics.

For the only years of his pro career, Rick averaged less than 20 points and his rebounding stats sagged, too. Still, he had plenty left in the tank. He set a personal high for assists in 1978-79 with 502, and captured two more free-throw titles, including an NBA record of 94.7 percent. Ricks deal with Houston expired in the spring of 1980. NBA general managers saw what appeared to be his drastic dip in production, and no one offered him a contract.

Rick retired as one of the most enigmatic players in NBA historynot to mention one of the league's best ever. Bill Sharman once called him the most productive offensive forward ever to play the game. The statistics bear him out. Over 10 NBA seasons, Rick averaged 23.2 points, 6.5 rebounds and 5.1 assists, while shooting an even 90 percent from the charity stripe. In the high-flying ABA, only Connie Hawkins and Julius Erving matched his all-around production. In both leagues, Rick was even better during the playoffs, where his competitive drive kicked into a brand new gear. Elected to the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 1986, he was named to the NBAs 50th Anniversary team a decade later.

A quick thinker and expert analyst during his playing days, Rick was a natural as a broadcaster. Network execs liked that he said what was on his mind. But his outspoken nature made him a target, too.

One source of tremendous distress was how his personal life was portrayed. Perhaps the most hurtful story was published in Sports Illustrated in December of 1991. Entitled "Daddy Dearest," it painted Rick as a disinterested, self-absorbed father and husband. He split up with his wife, Pamela, in 1979, and both emerged from the relationship embittered. Their four sonsScooter, Jon, Brent and Drewall dealt with the situation differently. But according to SI writer Bruce Newman, the scars of the divorce ran very deep.

Today, Rick hosts his own talk show (from noon to 3:00 every weekday) on KNBR in San Francisco. He also pens a regular column for the San Francisco Examiner. Guests on his radio show have included some of the sports world's biggest names, ranging from Bill Walton and Sandy Koufax to Mike Krzyzewski and Barry Bonds. In his role as a journalist, Rick makes no bones that hes a former pro athlete.

Rick is remarried. He and his wife, Lynn, have a son named Canyon. The family lives in Colorado. Rick is still involved in the lives of his four other sons. Scooter and Drew play professionally in Europe, while Brent is currently with the Seattle Supersonics and Jon with the Detroit Pistons.

Professional team(s)

* San Francisco Warriors (19651967)

* Oakland Oaks (19681969)

* Washington Caps (19691970)

* New York Nets (19701972)

* Golden State Warriors (19721978)

* Houston Rockets (1978-1980)

Career highlights and awards

* 1975 Finals MVP

* 1967 All-Star Game MVP

* 1966 Rookie of the Year

* 1× NBA Champion (1975)

* 6× All-NBA First Team (1966, 1967, 1974, 1975, 1976)

* 8× NBA All-Star (1966, 1967, 1973-78)

* 4× ABA All-Star (1969-72)

* 4× ABA First Team (1969-72)

* 1973 All-NBA Second Team

* NBA's 50th Anniversary All-Time Team (1996)