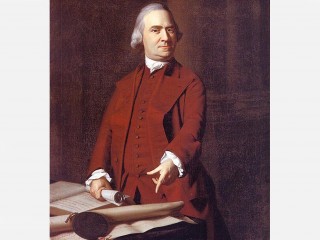

Samuel Adams biography

Date of birth : 1722-09-22

Date of death : 1803-10-02

Birthplace : Boston, Massachusetts, USA

Nationality : American

Category : Historian personalities

Last modified : 2010-10-01

Credited as : Statesman, colonial leader,

18 votes so far

A fundamental change in British policy toward the American colonies occurred after 1763, ending a long period of imperial calm. As Great Britain attempted to tighten control over its colonies, Adams was quick to sense the change, and his invective writings at first irritated and finally outraged the Crown officials. As a prime mover in the nonmilitary phases of colonial resistance, Adams undoubtedly pushed more cautious men, such as John Hancock, into leading Whig roles. However, his service in the Continental Congress and as a state official lacked political finesse. Once the struggle shifted from a war of words to one of ideas and finally of military encounters, Adams's influence declined.

Samuel Adams was born on Sept. 27, 1722, in Boston, Mass., the son of a prosperous brewer and a pious, dogmatic mother. When he graduated from Harvard College in 1740, his ideas about a useful career were vague: he did not want to become a brewer, neither did work in the Church appeal to him. After a turn with the law, this field proved unrewarding too. A brief association in Thomas Cushing's firm led to an independent business venture which cost Adams's family £1,000. Thus fate (or ill luck) forced Adams into the brewery; he operated his father's malt house for a livelihood but not as a dedicated businessman. In 1749 he married Elizabeth Checkley.

When his father suffered financial reverses, Adams accepted the offices of assessor and tax collector offered by the Boston freeholders; he held these positions from 1753 to 1765. His tax accounts were mismanaged and an £8,000 shortage appeared. There seems to have been no charge that he was corrupt, only grossly negligent. Adams was honest and later paid off the debts.

Adams's wife died in 1757 and in 1764 he married Elizabeth Wells, who was a good manager. His luck had changed, for he was about to move into a political circle that would offer personal opportunity unlike any in his past.

Growth in Politics

Adams became active in politics, and politics offered the breakthrough that transformed him from an inefficient taxgatherer into a leading patriot. As a member of the Caucus Club in 1764, he helped control local elections. When British policy on colonial revenues tightened during a recession in New England, passage of the Sugar Act in 1764 furnished Adams with enough fuel to kindle the first flames of colonial resistance. Thenceforth, he devoted his energies to creating a bonfire that would burn all connections between the Colonies and Great Britain. He also sought to discredit his local enemies--particularly the governor, Thomas Hutchinson.

Enforcement of the Sugar Act was counter to the interests of those Boston merchants who had accepted molasses smuggling as a way of life. They had not paid the old sixpence tax per gallon, and they did not intend to pay the new threepence levy. Urged on by his radical Caucus Club associates, Adams drafted a set of instructions to the colonial assemblymen that attacked the Sugar Act as an unreasonable law, contrary to the natural rights of each and every colonist because it had been levied without assent from a legally elected representative. The alarm "no taxation without representation" had been sounded.

Mature Propagandist

During the next decade Samuel Adams seemed a man destined for the times. His essays gave homespun, expedient political theories a patina of legal respectability. Eager printers hurried them into print under a variety of pseudonyms. Meanwhile Parliament unwittingly obliged men of Adams's bent by proceeding to pass an even more restrictive measure in the Stamp Act of 1765. Unlike the Sugar Act, this was not a measure that would be felt only in New England; Adams's audience widened as moderate merchants in American seaports now found more radical elements eager to force the issue of whether Parliament was still supreme "in all cases whatsoever." In one of many results, Governor Hutchinson's home was nearly destroyed by a frenzied anti-Stamp Act mob.

Adams's hammering essays and unceasing activities helped crystallize American opinion into viewing the Stamp Act as an odious piece of legislation. Through his columns in the Boston Gazette, he sent a stream of abuse against the British ministry; effigies of eminent Cabinet members hanged from Boston lampposts testified to the power of his incendiary prose. Adams rode a crest of popularity into the provincial assembly. As calm returned, he knew that the instruments of protest were developed and ready for use when the next opportunity showed itself.

The Townshend Acts of 1767 furnished Adams with a larger and more militant forum, projected his name into the front ranks of the patriot group, and earned him the hatred of the British general Thomas Gage and of King George III. Working with the Caucus Club, the radicals overcame local mercantile interests and demanded an economic boycott of British goods. This nonimportation scheme became a rallying point throughout the 13 colonies. Though its actual success was limited, Adams had proved that an organized, skillful minority could keep a larger but diffused group at bay. Adams worked with John Hancock to make seizure of the colonial ship Liberty seem a national calamity, and he welcomed the tension created by the stationing of British troops in Boston. Almost singlehandedly Adams continued his alarms, even after repeal of the Townshend duties.

In the succession of events from the Boston Massacre of 1770 to the Boston Tea Party and the Bill, Adams deftly threw Crown officials off guard, courted the radical elements, wrote dozens of inflammatory newspaper articles, and kept counsel with outspoken leaders in other colonies. In a sense, Adams was burning himself out so that, when the time for sober reflection and constructive political activity came, he had outlived his usefulness. By the time of the battles of Lexington and Concord in 1775, when he and Hancock were singled out as Americans not covered in any future amnesty, Adam's career as a propagandist and agitator had peaked.

Declining Power

Adams served in the Continental Congress between 1774 and 1781, but after the first session he occupied himself with gossip, uncertain as to what America's next steps should be or where he would fit into the scheme. He failed to perceive the forces loosed by the Revolution, and he was mystified by its results. While serving in the 1779 Massachusetts constitutional convention, he allowed his cousin John Adams to do most of the work. Tired of Hancock's vanity, he let their relationship cool; Hancock's repeated reelection as governor from 1780 on was a major disappointment. Against Daniel Shays's insurgents in 1786-1787, Adams shouted "conspiracy," showing little sympathy for the hard-pressed farmers.

As a delegate to the Massachusetts ratifying convention in 1788, Adams made a brief show as an old-time liberal pitted against the conservatives. But the death of his son weakened his spirit, and in the end he was intimidated by powerful Federalists. He was the lieutenant governor of Massachusetts from 1789 to 1793, when he became governor. As the candidate of the rising Jeffersonian Republicans, he was able to exploit the voter magnetism of the Adams name and was reelected for three terms. He did not seek reelection in 1797 but resisted the tide of New England federalism and remained loyal to Jefferson in 1800. He died in Boston on Oct. 2, 1803.