Thorpe Jim biography

Date of birth : 1888-05-28

Date of death : 1953-03-28

Birthplace : Oklahoma, United States

Nationality : American

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2010-06-20

Credited as : Athlete track and field, Football and basketball player,

1 votes so far

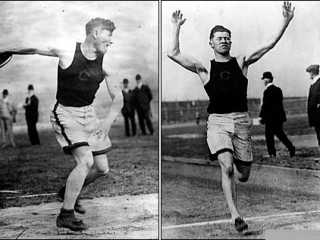

Born in a cabin in Indian Territory (now Oklahoma), the Sauk (or Sac) and Fox Indian athlete Jim Thorpe began a climb to fame in 1907 as a college track-and-field and football star at Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania. He competed in the 1912 Olympic Games in Stockholm, Sweden, where he won gold medals in both the pentathlon and the decathlon. His medals were stripped from him, however, after a journalist reported that Thorpe had briefly played baseball for pay during the summers of 1909 and 1910, nullifying his status as an amateur athlete. Thorpe went on to a career in professional football and baseball. Widely acclaimed as the greatest all-around athlete of modern times, he had a natural gift that enabled him to excel at almost any sport he played. In addition to track, football, and baseball, Thorpe was adept at swimming, lacrosse, basketball, wrestling, golf, and tennis. His awards were many, including being named the Greatest Male Athlete of the Half-Century in 1950 and America's Athlete of the Century in 1999. His Olympic medals and titles were restored posthumously, in 1982.

Beginning on the Bright Path

James Francis Thorpe was born in a cabin in the Sauk and Fox Indian settlement of Keokuk Falls, near present-day Prague, Oklahoma, on the morning of May 28, 1888 (some sources say 1887). His father was Hiram P. Thorpe, the son of Irishman Hiram G. Thorpe and No-ten-o-quah (Wind Woman) of the Sauk and Fox Thunder Clan of Chief Black Hawk. Thorpe's mother, Charlotte Vieux, was of French descent and of Potawatomi and Kickapoo Indian blood. She gave her son Jim the Indian name Wa-tho-huck, meaning "Bright Path" when she saw the path to the cabin illuminated by a ray of sunlight at dawn just after his birth.

Thorpe's father was a horse rancher and amateur athlete who taught his sons how to exercise as young boys. He also taught them the value of fair play and good sportsmanship, traits Thorpe would carry throughout his career as an athlete. Thorpe and his twin brother Charlie and their friends spent their free time fishing, trapping, playing follow-the-leader, and swimming. The boys also helped out with chores on the ranch. By the time Thorpe was fifteen he could catch, saddle, and ride any wild stallion.

In the spring of 1896, Charlie became ill with fever and shortly after died of pneumonia. The death of his twin left Thorpe with a deep emotional wound. His father enrolled him in the Haskell Institute, an Indian boarding school in Lawrence, Kansas, 300 miles away. There, Thorpe developed a love for football after watching the varsity team practice. The team's star fullback made Thorpe a football from strips of leather stuffed with rags. Thorpe began to organize his own games and was soon good enough to play with the older boys.

When Thorpe received word that his father had been shot while hunting and was dying, the twelve-year-old walked 270 miles home, a trip that took him two weeks. By the time he arrived, his dad had recovered. However, his mother died from blood poisoning just a few months later. Thorpe returned to the ranch and attended nearby Garden Grove school for the next three years, playing baseball after school with friends.

Carlisle Indian

In 1904, Thorpe was recruited to attend the highly respected Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. It was famous for its football team, the Carlisle Indians, which regularly beat the best Ivy League, military, and Big Ten college teams of the East. At 115 pounds and only 5'5 1/2" at age sixteen, Thorpe was too small to play on the varsity football team, but he won a spot on the tailor-shop team. Just as he was settling into Carlisle, however, Thorpe faced another tragedy: his father died of blood poisoning contracted while hunting.

One spring evening in 1907, the varsity track team discovered young Thorpe. It was the beginning of his track-and-field success as well as a relationship with track and football coach Glenn S. "Pop" Warner that would boost both their careers.

In the spring of 1908, Thorpe won a gold medal at the Penn Relays, with a jump of 6'1", and placed first in five events against Syracuse the following week. He went on to set a school record in the 220-yard hurdles, with a time of 26 seconds, a record he would later break by reaching his personal best time of 23.8 seconds.

By the 1908 football season, Thorpe weighed 175 pounds and was in great shape to start at left halfback. (Sources disagree about his later physical size. Some say he reached 5' 11" and 185 or 190 pounds, others say 6' 1" or 6' 2".) In what he later called the toughest football game of his life, he scored the only touchdown in a 6-6 tie against Penn State, a team loaded with all-American players. The Indians finished the season 10-2-1, outscoring their opponents 212 to 55. Thorpe was named a third-team all-American by leading football authority Walter Camp.

By the spring track season of 1909, Thorpe was reaching his peak. He won six gold medals in one meet and dominated every other for the rest of the season. When summer came, he followed two teammates to Rocky Mount, North Carolina, to play minor-league baseball. He accepted the manager's offer of $15 a week as "meal money." At the time, this practice was common among college athletes, but most used pseudonyms in order to keep their status as amateurs. Thorpe was unaware of the practice and used his own name. A few years later his lack of awareness would cost him dearly.

Thorpe left Carlisle and returned to Oklahoma during the fall of 1909. He worked on the family ranch, and then returned to North Carolina to play ball in the summer. In Oklahoma he bumped into his former teammate and track coach, Albert Exendine, who encouraged him to come back to Carlisle. The 1911 football season, with Thorpe back on the team and in fine form, made national headlines. Carlisle finished the season 11-1. Thorpe was named first-team all-American halfback, and his teammates elected him captain.

The 1912 Olympics

Thorpe's fame had followed him to the 1912 Olympics in Stockholm, Sweden, where he would compete against the best athletes of the time in both the pentathlon-introduced that year by the Swedes-and the decathlon, a grueling ten-event competition. During the pentathlon, he placed first in the running broad jump, with a leap of 23' 2.7". Although he had thrown a javelin for the first time only two months earlier, Thorpe placed fourth in this event. He finished first in the 200-meter dash, with a time of 22.9 seconds. His discus throw distance measured 116' 8.4", almost three feet ahead of the second place winner. In the 1,500-meter run, Thorpe paced himself, staying behind until the middle of the second lap, when he picked up speed. He had passed all other runners by the beginning of the fourth lap and easily finished first, with a time of 4 minutes 44.8 seconds. With a total score of 7, compared to 21 received by the second place winner, Thorpe won the gold.

Five days later, the long-anticipated decathlon began. The athletes competed in the pouring rain on the first day of the three-day event. Thorpe placed third in the 100-meter dash, second in the running broad jump, and then threw the shot put 42' 5 9/20", more than 2.5 feet further than the second place winner. On a beautiful second day, he placed first in the high jump, fourth in the 400-meter run, and first in the 110-meter hurdles with a time of 15.6 seconds, a time that would not be approached until the 1948 Olympics, when Bob Mathias completed the hurdles in 15.7 seconds. On the third day, Thorpe placed second in discus, third in pole vault, third in the javelin throw, and then beat his pentathlon time in the 1,500-meter run, finishing in 4 minutes 40.1 seconds. He won the decathlon and the gold medal with a total of 8,412.95 points out of a possible 10,000. He finished almost 700 points ahead of Hugo Wieslander of Sweden, the silver medalist.

One of the most famous stories about Thorpe revolves around his acceptance of his second gold medal from King Gustav V of Sweden. As the king presented the medal and a bejeweled chalice as a gift, he grabbed Thorpe's hand and said, "Sir, you are the greatest athlete in the world." Thorpe answered simply, "Thanks, King."

By the time Thorpe and his fellow Olympians returned home, he was an international hero and celebrity, treated to ticker-tape parades in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia, and honored with banquets and parties. Bob Bernotas reported that the 24-year-old Indian was overwhelmed. "I heard people yelling my name, and I couldn't realize how one fellow could have so many friends," he said.

Greatest Football Season

The year 1912 brought Thorpe not only two Olympic gold medals, but it proved to be his greatest football season as well. He helped the Carlisle Indians to a season finish of 12-1-1. The team set a national record, scoring 504 points and allowing only 114. Thorpe scored 198 of those 504 points, setting an all-time record. Camp again named him a first-team all-American.

In a November 1912 game against the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, future five-star general and U.S. president Dwight D. Eisenhower played halfback and faced Thorpe. Bernotas wrote that Eisenhower later recalled, "On the football field there was no one like him in the world. Against us he dominated all of the action. . . . I personally feel no other athlete possessed his all-around abilities in games and sports."

AAU Strikes Blow

In January 1913, a reporter learned that Thorpe had played baseball for pay in North Carolina a few years earlier. By the end of the month, the story broke nationwide that Thorpe was a professional athlete and should not have been allowed to compete in the Olympics. The AAU demanded a letter from Thorpe, and he sent one, drafted with Warner's help, saying he "was not wise in the ways of the world and did not realize this was wrong." He said he only played baseball because he enjoyed it, not for the money, and that he hoped the AAU and his fans would "not be too hard in judging" him. However, the unyielding AAU erased Thorpe's records from the books and asked for his medals and awards back. On Warner's advice, he returned them, and the AAU gave them to the second-place winners.

In spite of the disgrace, both national and international fans and the press were on his side throughout the ordeal. Their support helped him to go on with his career. Yet, the supposed misdeed haunted him for the rest of his life.

Professional Sports

In 1913, after receiving offers from six major-league baseball clubs, Thorpe left Carlisle and joined manager John McGraw's New York Giants. The easygoing Indian had trouble getting along with McGraw, and Thorpe performed better when away from the tough manager, farmed out to the minor leagues, and during a brief stint with the Cincinnati Reds. In 1919, McGraw supposedly called Thorpe a "dumb Indian" after he missed a signal and cost the team a run. Thorpe's pride got the better of him, and he went after McGraw. He was traded to the Boston Braves soon afterward for a final season in pro baseball. After leaving Boston he played minor league ball for the next nine summers, finishing his baseball career at Akron, Ohio, in 1928.

In the fall of 1915, Thorpe joined Jack Cusack's Canton (Ohio) Bulldogs pro football team. The team did so well with gate receipts that next season Cusack hired several all-American players. Thorpe stayed with the team each fall through 1920, while continuing to play pro baseball during the summers. In 1919 the Bulldogs ended the season undefeated, with an unofficial world championship.

After leaving the Bulldogs, Thorpe joined the Cleveland Tigers for one season and then became a part of the Oorang Indians, who spiced their games with Indian dances and hunting exhibitions. In 1924, at age thirty-six, he joined the Rock Island Independents and also played briefly with the New York Giants football team. He rejoined Canton in 1926 but played only a few games to please the fans. He played his final games with the Chicago Cardinals in 1928.

Thorpe excelled at every aspect of football: kicking, running, passing, and tackling. He was famous for his innovative body block, in which he rammed his big shoulder into a player's legs or upper body, often causing a fumble. He then grabbed the ball and ran for a touchdown. Knute Rockne often told the story about how he once tackled Thorpe, who said, "You shouldn't do that, Sonny. All these people came to watch old Jim run." The next time, Thorpe brought him down with his shoulder and ran forty yards for a touchdown before trotting back and telling him, "That's good, Sonny, you let old Jim run." Dozens of other players told the same story over the years, with themselves as "Sonny."

Later Years

When his professional sports career came to an end, Thorpe was at a loss to find another. Living in the Los Angeles area, he emceed dance marathons and sporting events, worked as a painter and laborer, and acted bit parts in western movies. When the 1932 Olympics were to be held in Los Angeles, word got out that Thorpe lived in the city but could not afford a ticket to the games. Fans sent money so he could attend, and when he took his seat the crowd of 105,000 gave him a standing ovation.

In 1937 Thorpe became involved in a campaign to abolish the Bureau of Indian Affairs and then worked for a while as a public speaker, advocating better living conditions for American Indians.

Thorpe suffered the first of three heart attacks in 1942. In 1945 he was called to serve in the U.S. merchant marine. After World War II, Thorpe became a strong advocate of athletic programs for children. At age sixty, in exhibitions in San Francisco and New York, he kicked the football over the goal post from the fifty-yard line and punted the ball up to seventy-five yards.

The Greatest Athlete

In 1950, Associated Press polls of sportswriters and commentators elected Thorpe the Greatest Football Player of the Half-Century and the Greatest Male Athlete of the Half-Century. Thorpe was the first choice of 252 of the 391 journalists.

In 1951, a movie about his life, Jim Thorpe-All-American, premiered, starring Burt Lancaster. Thorpe had served as adviser on the film, showing Lancaster how to kick a football.

In 1951, Thorpe suffered a second heart attack. Although he quickly recovered from that attack, he had a third, massive, attack while eating lunch at home in Lomita, California, on March 28, 1953. He died soon afterward. A front-page obituary in the New York Times called the loss of his Olympic medals a tragedy that should have long been rectified and said, "His memory should be kept for what it deserves--that of the greatest all-round athlete of our time."

After a Catholic funeral, Thorpe's body was supposed to have been buried in Oklahoma. However, his wife, Patricia, offered it to the economically struggling town of Mauch Chunk, Pennsylvania, if the town would change its name to Jim Thorpe. The people voted to do so, and to merge the neighboring town of East Mauch Chunk into the bargain. A large monument to Thorpe was erected, and his body was transferred to Pennsylvania.

Restoration of Medals

In 1973 the AAU finally restored Thorpe's amateur status for 1909-1912. In 1975 the U.S. Olympic Committee reinstated Thorpe, and in 1982, after a lengthy campaign by Thorpe's sons and daughters and many supporters, the International Committee agreed to restore Thorpe's status and return replicas of the medals.

Thorpe is considered the greatest American male athlete in history. He was named "The Legend" on the all-time NFL team; his statue graces the lobby of the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio, and his portrait hangs in the Oklahoma State Capitol. The NFL's annual most valuable player award is called the Jim Thorpe Trophy. In 1996, the Atlanta Committee for the Olympic Games honored his memory by routing the Olympic torch relay through his birthplace of Prague, Oklahoma. In 1999, the U.S. House and Senate passed resolutions designating Thorpe America's Athlete of the Century.

AWARDS

1908, Tied for first place in high jump at Penn Relays, taking home gold medal after flip of a coin; 1908, Named third-team All-American by Walter Camp after first season as halfback with Carlisle Indians, who finished 10-2-1; 1909, Wins six gold medals and one bronze in Lafayette-Carlisle track meet; 1911, Selected first-team All-American by Camp after Carlisle Indians finish season 11-1, losing the one game by only one point; 1912, Won gold medals in pentathlon and decathlon at fifth Olympiad in Stockholm, Sweden; 1912, Won Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) All-Around Championship decathlon with 7,476 points, breaking old record of 7,385 points, in spite of being weakened by ptomaine poisoning and hampered by bad weather; 1912, Named first-team All-American for second consecutive year after Carlisle Indians finish season 12-1-1, leading the nation in scoring, with 504 points; 1920, Named first president of American Professional Football Association (APFA), which two years later was renamed National Football League (NFL); 1950, Selected by Associated Press polls as Greatest Football Player of the Half-Century and Greatest Male Athlete of the Half-Century; 1951, Named to National College Football Hall of Fame; 1951, Monument to Thorpe is erected in Carlisle, Pennsylvania; 1953, Towns of Mauch Chunk and East Mauch Chunk, Pennsylvania, combine and are renamed Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania; 1955, NFL names its annual most valuable player award the Jim Thorpe Trophy; 1958, Elected to National Indian Hall of Fame in Anadarko, Oklahoma; 1961, Elected to Pennsylvania Hall of Fame; 1963, Inducted as charter member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio; life-size statue of Thorpe adorns lobby; 1966, Portrait of Thorpe painted by Charles Banks Wilson unveiled in Oklahoma State Capitol; hangs alongside portraits of U.S. Senator Robert S. Kerr, Sequoyah, and Will Rogers; 1973, House in which Thorpe's family lived from 1917 to 1923, in Yale, Oklahoma, opened as historic site by Oklahoma Historical Society; 1975, Enshrined in National Track and Field Hall of Fame; 1975, Portion of Oklahoma Highway 51 renamed Jim Thorpe Memorial Highway; 1977, Named Greatest American Football Player in History in national poll conducted by Sport Magazine; 1984, U.S. Government issues Jim Thorpe postage stamp; 1996, Honored by Atlantic Committee for the Olympic Games by routing the Olympic torch relay through birthplace of Prague, Oklahoma; 1996-2001, Named ABC's Wide World of Sports Athlete of the Century; 1999, Named America's Athlete of the Century by a resolutions of the U.S. House of Representatives and Senate.