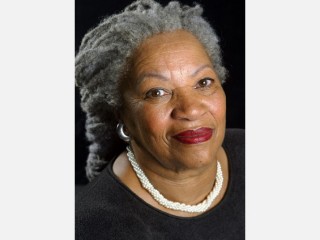

Toni Morrison biography

Date of birth : 1931-02-18

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Lorain, Ohio, United States

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2010-10-01

Credited as : Novelist, won the Pulitzer Prize in 1988, for the novel "Beloved"

8 votes so far

Toni Morrison is best known for her intricately woven novels, which focus on intimate relationships, especially between men and women, set against the backdrop of African American culture. She won the 1988 Pulitzer Prize for her fifth novel, Beloved, and the 1993 Nobel Prize for literature.

Chloe Anthony Wofford, better known in the literary world as Toni Morrison, was born in Lorain, Ohio, in 1931 to Ramah and George Wofford. Her maternal grandparents, Ardelia and John Solomon Willis, had left Greenville, Alabama, around 1910 after they lost their farm. Morrison's paternal family left Georgia and headed north to escape sharecropping and racial violence. Both families settled in the steel-mill town of Lorain on Lake Erie.

Morrison's childhood was filled with the African American folklore, music, rituals, and myths which were later to characterize her prose. Her mother sang constantly, much like the character "Sing" in Song of Solomon, while her Grandmother Willis (reminiscent of Eva Peace in Sula and Pilate Dead in Song of Solomon) kept a "dream book," in which she tried to decode dream symbols into winning numbers. Her family was, as Morrison says, "intimate with the supernatural" and frequently used visions and signs to predict the future. Her real life world, therefore, was often reflected later in her novels. Morrison attributes the breadth of her vision to the precision of her focus. She sees her literature as functioning much as did the oral storytelling tradition of the past that reminded members of the community of their heritage and defining their roles.

Choosing a Literary Career

Morrison cited the difficulty people at Howard University had in pronouncing "Chloe" as the reason for changing her name to Toni. While at Howard she was a member of the Howard University Players, a repertory company that presented plays about the lives of African American people in the South during the 1940s and 1950s. This experience brought into focus her own family's history of lost land and racial violence. Years later this theme would appear time and time again in her fiction.

After receiving the B.A. in English from Howard and the M.A. from Cornell, also in English, Morrison returned to Howard to teach. In 1958 she married Harold Morrison, a young architect from Jamaica who also taught at Howard. The marriage, which ended in divorce in 1964, produced two sons, Harold (also known as Ford) and Slade. A year and half later she was in Syracuse, New York, working as a textbook editor for a subsidiary of Random House, with two small children, and with lots of free time in the evenings. This environment helped her turn to writing novels.

For several years Morrison continued as a senior editor at Random House, where she became a force in getting other African-American writers published, including Toni Cade Bambara, Gayl Jones, and June Jordan. She not only held down this job, but taught part-time and lectured across the country, while at the same time writing novels: The Bluest Eye (1970); Sula (1974), which was nominated for a National Book Award; Song of Solomon (1977), which won a National Book Critics Circle Award in 1977 and an American Academy of Arts and Letters Award and was chosen as the second novel by an African American to be a Book-of-the-Month selection (the first was Richard Wright's Native Son in 1940); Tar Baby (1981); and Beloved (1987) a novel of recovering power out of the devastation of slavery. Meanwhile she served as writer-in-residence at New York State University, first at Stony Brook and later at Albany, before moving to Princeton.

Morrison's novels were characterized by carefully crafted prose, in which ordinary words were placed in relief so as to produce lyrical phrases and to elicit sharp emotional responses from her readers. Her extraordinary, mythic characters were driven by their own moral visions to struggle in order to understand truths which are larger than those held by the individual self. Her subjects were large: good and evil, love and hate, friendship, beauty and ugliness, and death.

Making Her Point Through Fiction

The Bluest Eye depicted the tragic life of a young black girl, Pecola Breedlove, who wanted nothing more than to have her family love her and to be liked by school friends. These rather ordinary ambitions, however, were beyond Pecola's reach. She surmised that the reason she was abused at home and ridiculed at school was her black skin, which was equated with ugliness. She imagined that everything would be all right if she had blue eyes and blond hair; in short, if she were cute like Shirley Temple. Unable to withstand the assaults on her frail self-image, Pecola goes quietly insane and withdraws into a fantasy world in which she was a beloved little girl because she has the bluest eye of all.

Against the backdrop of Pecola's story was that of Claudia and Frieda MacTeer, who managed to grow up whole despite the social forces which pressured African-Americans and females. For them, childhood was much like it was for Morrison herself in Lorain; their egos were comforted and nurtured by family members, whose love did not fail them.

Sula was about a marvelously unconventional woman, Sula Pease, who becomes a pariah in her hometown of Medallion, Ohio, which was much like Lorain. With the discovery at the age of 12 that she and her friend Nel Wright "were neither white nor male, and that all freedom and triumph was forbidden to them, they set about creating something else to be." Nel married and her life follows convention, while Sula's life evolved into an unlimited experiment. Not bound by any social codes, Sula was first thought to be unusual, then outrageous, and eventually evil. In becoming a pariah in her community, she was the measure for evil and, ironically, inspired goodness in those around her. At her death both the community and Nel learned that Sula was their life force; she was the other half of the equation. Without Sula, Nel felt incomplete.

The female vantage point shifted to an African-American male perspective in Song of Solomon, which traced the process of self-discovery for Macon Dead III. Macon, or "Milkman" as he was called by his friends, set out on a series of journeys to recover a lost treasure in his family's past, but instead of discovering economic wealth, he uncovered something more valuable. He gathered together the details of his ancestry, which he thought had been lost to him forever. In a larger context Milkman's odyssey became a kind of cultural epic for all African-American people; it mapped in symbolic fashion the heritage of a people, from a mythic African past, through a heritage obscured by slavery, to a present built upon questioned values.

Tar Baby, Morrison's fourth novel, moved beyond the small Midwestern town setting to an island in the Caribbean. As the title suggested, the story employed a folktale about how a farmer used a tar baby to catch a troublesome rabbit. When the tar baby doesn't return the rabbit's greeting, he hits the tar baby and gets stuck. He begs the farmer to skin him alive, to do anything but throw him into the briar patch. The farmer throws him in the briar patch, where the rabbit escapes.

As the story opens, Jadine (also called Jade) has left Paris, where she was a fashion model, to visit Valerian and Margaret Street in the Caribbean. Jade, who was orphaned at an early age, has been cut off from her black heritage. She was raised and educated by Valerian Street, a rich, white, retired candy magnate and employer for her aunt and uncle, Sydney and Ondine. Valerian has paid for Jade's French education, and she has substituted Valerian's cultural heritage of wealth and status for her black heritage of struggle and survival. Therefore, Jade was an orphan in the literal sense of the word, with no personal attachments.

On Christmas Eve a young black vagrant, Son, jumped ship and intruded on their lives. His presence brings to the surface years of their locked up secrets and forced them to give expression to their violent racial, sexual, and familial conflicts. Jade and Son became passionately entangled with one another. Because she had no racial past, no tribe, to cling to--no briar patch, as it were--she cannot share his life with him, but he does not want to live without her. She flees from him, and he searches for her.

Beloved, Morrison's fifth novel, has been called one of her most technically sophisticated works. Using flashbacks, fragmented narration and shifting viewpoints, Morrison explored the story of the events that have led to the protagonist Sethe's crime. Sethe lived with her surviving daughter, Denver, on the outskirts of Cincinnati in a farmhouse haunted by the tyrannical ghost of her murdered baby daughter. Paul D., fellow slave from Kentucky comes to live with them. He violently casts out the baby spirit or so they think, until one day a beautiful young stranger with no memory arrived, calling herself 'Beloved'. The stranger was the embodiment of Sethe's murdered daughter and the collective anguish and rage of sixty million and more who have suffered the tortures of slavery. She eventually takes over the household, feeding on Sethe's memories and explanations to gain strength. Beloved nearly destroyed her mother until the community of former slave women who have ostracized Sethe and Denver since the murder join together to exorcise Beloved at last.

Although the work was considered Morrison's masterpiece, she failed to win either the National Book Award or the National Book Critic's Award. Forty-eight prominent African-American writers and critics who were outraged and appalled at the lack of recognition for the novel, signed a tribute to her achievement that was published in the New York Times in January 1988. Later that year Morrison won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for Beloved. She won the Nobel Prize for literature based upon the quality of her work in 1993. In 1996, the National Book Awards presented her with its NBF Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters. During her acceptance speech Morrison said "writing is a craft that seems solitary but needs another for its completion, that requires a whole industry for its dissemination. At its best, it offers the fruits of one person imaginative intelligence to another without restraints."

In 1993 Morrison became the first black woman to receive the Nobel Prize in literature. In awarding her the honor, the Swedish Academy called Morrison "a literary artist of the first rank," and commended her ability to give "life to an essential aspect of American reality" in novels "characterized by visionary force and poetic import." The Academy also asserted that Morrison "delves into the language itself, a language she wants to liberate from the fetters of race. And she addresses us with the luster of poetry."

Morrison's next novel, Paradise (1998), was generally warmly received by critics who found that the novel lived up to Morrison's previous works. The backdrop of the story is the settling of former slaves in the western United States in the nineteenth century. A group of African American men bring their wives and children to Oklahoma and found the town of Haven, where the inhabitants are haunted throughout the twentieth century by a past of bondage and the rejection they suffer by light-skinned members of their own race. The novel also tackles the issues of female rebellion against a patriarchal society and the search for paradise--some sort of happiness and security--in a less than perfect world.

In addition to her award-winning fiction, Morrison also published Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination (1992), her first work of literary criticism. In the book, which began as a series of lectures she presented at Harvard University, Morrison argues that the importance of black characters in American literature has been downplayed by literary critics.

In 1999, Morrison's first children's book, The Big Box was published. A collaboration with her son, Slade, the book offered a through-a-glass-darkly vision of modern American childhood that pushes kids and parents to take a fresh look at the rules and values that structure their lives. The book reflects on the ways in which well-meaning adults sometimes hinder children's independence and creativity. In April of 2000, Oprah Winfrey chose Morrison's novel The Bluest Eye as the month's selection for "Oprah's Book Club."

Being on Oprah's book list helped Morrison gain a new legion of fans, and she treated them to a new novel in 2003, simply titled Love. Though the book is much slimmer than most Morrison tomes--this one checks in at just over 200 pages--it features Morrison's same unapologetic writing style. The story revolves around the dysfunctional family of Bill Cosey, owner of the once-prominent Cosey Resort where upper-middle-class blacks came during times of segregation. As the story unfolds, his wife and granddaughter fight for the estate and a tangle of history and lies and illusions entraps them.

Morrison tried children's literature once again in 2004, with a piece called Remember: The Journey to School Integration. The book contains archival photographs of actual young African Americans who endured the turbulent times of school integration. To write the book, Morrison looked at the photos, then tried to imagine the thoughts and feelings of those pictured. Her fictional interpretations accompany the photos. Interspersed throughout the book are factual pages that set the scene for the story. The book was published in 2004, on the 50th anniversary of the Brown v. Board of Education ruling, which integrated schools. According to Newsweek, Morrison writes in the book, "Our parents sued the Board of Education not because they hate them but because they love us."

Morrison began collaborating with her younger son, Slade, in the early 2000s, and the two wrote several children's books together. The Book of Mean People, stars a rabbit who encounters various mean people, and explores the feelings children have when others are overbearing and rude and make them feel angry or powerless. The book not only lets children know that it's all right to feel negative emotions, but also gently reminds parents that when they are angry and take it out on their kids, it hurts the children.

Morrison and Slade next wrote a series of retellings of Aesop's fables, in a hip-hop style. The fables don't end in the traditional manner; the Morrisons wanted to give fresh meanings to the tales. They suggest that a victim can strike back; the fool can become smart; the frightened can become courageous; the weak can get strong. Titles included Who's Got Gamee? The Ant or the Grasshopper? (2003), Who's Got Game? The Lion or the Mouse? (2003), and Who's Got Game? The Poppy or the Snake? (2004).

In 2009, Morrison returned to adult fiction with the novel, A Mercy, which like her earlier novels explores issues of gender and race. Set in the seventeenth century, the book explores a time when slavery was less related to race and more related to indebtedness and social origin. The characters include a black child, an orphan, and two indentured servants, who all suffer in a culture of servitude. From The Bluest Eye to A Mercy, Morrison's work compels readers to consider issues that involve race but also transcend it, as they often see their own world, and perhaps even themselves, reflected in the pages of each novel.