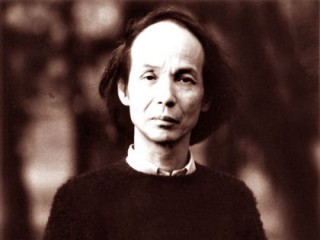

Toru Takemitsu biography

Date of birth : 1930-10-08

Date of death : 1996-02-20

Birthplace : Tokyo, Japan

Nationality : Japanese

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2012-02-17

Credited as : Composer, writer on aesthetics and music theory, style of the Western avant-garde

0 votes so far

Western art music from the mid-twentieth century onward has often greatly benefitted from Eastern influences. Various composers have featured traditional Asian instruments, used Eastern compositional and improvisational techniques, and attempted to transfer aesthetics of the East to Western music. While often the result is an interesting juxtaposition of Eastern and Western features, one may well wonder whether the complete integration of Eastern and Western musical traditions is indeed possible or even desirable. British author Rudyard Kipling once wrote that "East is East and West is West, and never the twain shall meet." Nonetheless, it would seem that the music of Japan's leading composer, Toru Takemitsu, achieves precisely this, a thorough integration of materials from both the East and West that results in a new and different world of sound, a music whose coherency is derived equally from both traditions.

Takemitsu was born in Tokyo, Japan, in 1930. He first decided to pursue a career in music when he was in his teens at the end of World War II. Recalling this time in an interview for the Los Angeles Herald Examiner, Takemitsu said that he was "very negative about everything Japanese. During the war it was forbidden to listen to anything but Japanese music, and we were thirsty to hear music of the West and wanted to learn just that music. Only afterwards could I find my own way to Japanese tradition."

At age 18 Takemitsu studied composition privately with Yosuji Kiyose, but otherwise is self-taught and holds no degrees in music. He told Edward Downes, program annotator for the New York Philharmonic Orchestra, that his teacher was "his daily life, including all of music and nature." It is probably this lack of formal musical education and prolonged study with no particular composer that in part accounts for Takemitsu's highly original style--and this in spite of his experimenting with every new musical method and current among other contemporary composers since World War II.

Takemitsu's compositions demonstrate the entire gamut of compositional features current in the West: In addition to conventional features, he uses improvisation, non-musical notation, electro-acoustic means of composition on tape, unusual instrumentation, and instrumental passages of such difficulty that they challenge the ability of even the most seasoned performers. Yet, all of Takemitsu's compositions have some added quality--which the composer says is their bicultural nature--which distinguishes them from the rest of Western music that uses these same techniques. He told Downes, "Maybe it can be said that I am rather a gardener, not a composer. I don't like to construct sounds as great architecture the way Beethoven did. My music is different. I set up a place where sounds meet each other. I don't construct but create some order which makes my music quite close to the idea of a Japanese garden. In the garden there are different cycles, short and long; there is mobility and immobility. The growing of trees and the growing of grass is different you know."

Takemitsu has not always been able to use the word "bicultural" to describe his music. In the 1950s his music was entirely in the style of the Western avant-garde; only in the 1960s did he become seriously interested in traditional Japanese instruments, such as the lute-like biwa, and begin to combine them with Western instruments. By the 1970s his integration of Eastern and Western elements was nearly complete. While the ensembles and compositional technique are for the most part Western, the spirit of Takemitsu's music is Eastern and almost always evokes natural phenomena. His greatest artistry lies in creating timbres and textures, and the titles of his compositions most frequently allude to sound or sound color as it occurs in nature, for example, Garden Rain, Waves, In an Autumn Garden.

As Bernard Rands pointed out in the Musical Times, such titles are quite different from "abstract or technological ideas contained in the thousands of titles that dominate contemporary music publishers' catalogues: Fragments, Formants, Phonics, Prisms, Variants, Collage, Projections etc. The complexity of experience implied in Takemitsu's titles is universal human experience whereas the complexity of technical abstract ideas implied in the others is Western, local, culturally conditioned in its cerebral, esoteric concern with process."

Rather than having an all-consuming interest in the process of composing or in abstract musical problems, Takemitsu is intrigued by the contemplation of natural phenomena. Thus he has not written extensively about his own compositional procedure as the overwhelming majority of contemporary composers have, and what writing and lecturing he has done do not include any particular terminology to explain his compositional techniques. Instead, Takemitsu tends to focus on the listener's potential response.

Aside from his talent in the realm of sound and sound colors, Takemitsu's music is also unique in its pacing. The listener may get the impression that the music evolves on its own, a characteristic that is directly related to Takemitsu's evocation of natural phenomena. The structure and climax of his works are often strictly non-Western and thus the aspect of his music the most often misunderstood by Western listeners. Ellen Pfeifer, writing for the Boston Herald, said that there is an "unfortunate sameness about [Takemitsu's] writing--unvarying dynamic level (quiet) and pace (slowish)." The Japanese critic Hidekazu Yoshida, writing for a Japanese recording of Takemitsu's works, observed that "in Japanese music, however, it is not unusual for one to bring out the climax, which is supposed to be the cardinal element in the work concerned, very abruptly and without any preparation, or suddenly to cut it.... This traditional sense of beauty of the Japanese has been revived in a very vivid way in Takemitsu's work. I do not think it was done unconsciously. This is the reason why a piece which at first may sound monotonous and lacking in compactness of structure leaves one with a generally fresh memory after one has listened to it."

Takemitsu gained his greatest international acclaim as a result of the immediate success of his 1967 work, November Steps, commissioned and performed by the New York Philharmonic as part of its 125th anniversary celebration. He continues to be an active and successful composer with a large catalog of published works for all media, including cinema, radio, and television. He is also a frequent lecturer and composer-in-residence at music schools and festivals throughout the world.

He died of pneumonia on February 20, 1996, while undergoing treatment for bladder cancer .