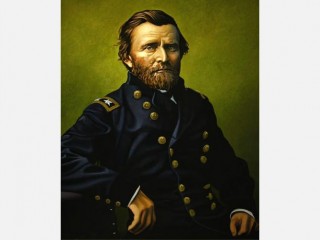

Ulysses S. Grant biography

Date of birth : 1822-04-27

Date of death : 1885-06-23

Birthplace : Clermont County, Ohio

Nationality : American

Category : Arts and Entertainment

Last modified : 2010-06-08

Credited as : President of U.S., general in the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln

24 votes so far

Ulysses Simpson Grant (1822-1885), having led the Northern armies to victory in the Civil War, was elected eighteenth president of the United States.

As a general in the Civil War, Ulysses S. Grant possessed the right qualities for prosecuting offensive warfare against the brilliant tactics of his Southern adversary Robert E. Lee. Bold and indefatigable, Grant believed in destroying enemy armies rather than merely occupying enemy territory. His strategic genius and tenacity overcame the Confederates' advantage of fighting a defensive war on their own territory. However, Grant lacked the political experience and subtlety to cope with the nation's postwar problems, and his presidency was marred by scandals and an economic depression.

Ulysses S. Grant was born on April 27, 1822, in a cabin at Point Pleasant, Ohio. He attended district schools and worked at his father's tannery and farm. In 1839 Grant's father secured an appointment to West Point for his unenthusiastic son. Grant excelled as a horseman but was an indifferent student. When he graduated in 1843, he accepted an infantry commission. Although not in sympathy with American objectives in the war with Mexico in 1846, he fought courageously under Zachary Taylor and Winfield Scott, emerging from the conflict as a captain.

In subsequent years Capt. "Sam" Grant served at a variety of bleak army posts. Lonely for his wife and son (he had married Julia Dent in 1848), the taciturn, unhappy captain began drinking. Warned by his commanding officer, Grant resigned from the Army in July 1854. He borrowed money for transportation to St. Louis, Mo., where he joined his family and tried a series of occupations without much success: farmer, realtor, candidate for county engineer, and customshouse clerk. He was working as a store clerk at the beginning of the Civil War in 1861.

Rise to Fame

This was a war Grant did believe in, and he offered his services. The governor of Illinois appointed him colonel of the 21st Illinois Volunteers in June 1861. Grant took his regiment to Missouri, where, to his surprise, he was promoted to brigadier general.

Grant persuaded his superiors to authorize an attack on Ft. Henry on the Tennessee River and Ft. Donelson on the Cumberland in order to gain Union control of these two important rivers. Preceded by gunboats, Grant's 17,000 troops marched out of Cairo, Ill., on Feb. 2, 1862. After Ft. Henry surrendered, the soldiers took Ft. Donelson. Here Confederate general Simon B. Buckner, one of Grant's West Point classmates (and the man who, much earlier, had loaned the impecunious captain the money to rejoin his family), requested an armistice. Grant's reply became famous: "No terms except an unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted. I propose to move immediately upon your works." Buckner surrendered. One of the first important Northern victories of the war, the capture of Ft. Donelson won Grant promotion to major general.

Grant next concentrated 38,000 men at Pittsburgh Landing (Shiloh) on the Tennessee River, preparing for an offensive. He unwisely neglected to prepare for a possible Confederate counteroffensive. At dawn on April 6, 1862, the Confederate attack surprised the sleeping Union soldiers. Grant did his best to prevent a rout, and at the end of the day Union lines still held, but the Confederates were in command of most of the field. The next day the Union Army counterattacked with 25,000 fresh troops, who had arrived during the night, and drove the Southerners into full retreat. The North had triumphed in one of the bloodiest battles of the war, but Grant was criticized for his carelessness. Urged to replace Grant, President Abraham Lincoln refused, saying, "I can't spare this man--he fights."

Grant set out to recoup his reputation and secure Union control of the Mississippi River by taking the rebel stronghold at Vicksburg, Miss. Several attempts were frustrated; in the North criticism of Grant was growing and there were reports that he had begun drinking heavily. But in April 1863 Grant embarked on a bold scheme to take Vicksburg. While he marched his 20,000 men past the fortress on the opposite (west) bank, an ironclad fleet sailed by the batteries. The flotilla rendezvoused with Grant below the fort and transported the troops across the river. In one of the most brilliant gambles of the war, Grant cut himself off from his base in the midst of enemy territory with numerically inferior forces. The gamble paid off. Grant drove one Confederate Army from the city of Jackson, then turned and defeated a second force at Champion's Hill, forcing the rebels to withdraw to Vicksburg on May 20. Union troops laid siege to Vicksburg, and on July 4 the garrison surrendered. Ten days later the last Confederate outpost on the Mississippi fell. Thus, the Confederacy was cut in two. Coming at the same time as the Northern victory at Gettysburg, this was the turning point of the war.

Grant was given command of the Western Department, and in the fall of 1863 he took command of the Union Army pinned down at Chattanooga after its defeat in the Battle of Chickamauga. In a series of battles on November 23, 24, and 25, the rejuvenated Northern troops dislodged the besieging Confederates, the most spirited infantry charge of the war climaxing the encounter. It was a great victory; Congress created the rank of lieutenant general for Grant, who was placed in command of all the armies of the Union.

Architect of Victory

Grant was at the summit of his career. A reticent man, unimpressive in physical appearance, he gave few clues to the reasons for his success. He rarely communicated his thinking; he was the epitome of the strong, silent type. But Grant had deep resources of character, a quietly forceful personality that won the respect and confidence of subordinates, and a decisiveness and bulldog tenacity that served him well in planning and carrying out military operations.

In the spring of 1864 the Union armies launched a coordinated offensive designed to bring the war to an end. However, Lee brilliantly staved off Grant's stronger Army of the Potomac in a series of battles in Virginia. Union forces suffered fearful losses, especially at Cold Harbor, while war weariness and criticism of Grant as a "butcher" mounted in the North.

Lee moved into entrenchments at Petersburg, Va., and Grant settled down there for a long siege. Meanwhile, Gen. William T. Sherman captured Atlanta and began his march through Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina, cutting what remained of the Confederacy into pieces. In the spring of 1865 Lee fell back to Appomattox, where on April 9 he met Grant in the courthouse to receive the generous terms of surrender.

Postwar Political Career

After Lincoln's death Grant was the North's foremost war hero. Both sides in the Reconstruction controversy, between President Andrew Johnson and congressional Republicans, jockeyed for his support. A tour of the South in 1865 convinced Grant that the "mass of thinking men" there accepted defeat and were willing to return to the Union without rancor. But the increasing defiance of former Confederates in 1866, their persecution of those who were freed (200,000 African Americans had fought for the Union, and Grant believed they had contributed heavily to Northern victory), and harassment of Unionist officials and occupation troops gradually pushed Grant toward support of the punitive Reconstruction policy of the Republicans. He accepted the Republican presidential nomination in 1868, won the election, and took office on March 4, 1869.

Grant was, to put it mildly, an undistinguished president. His personal loyalty to subordinates, especially old army comrades, prevented him from taking action against associates implicated in dishonest dealings. Government departments were riddled with corruption, and Grant did little to correct this. Turmoil and violence in the South created the necessity for constant Federal intervention, which inevitably alienated large segments of opinion, North and South. In 1872 a sizable number of Republicans bolted the party, formed the Liberal Republican party, and combined with the Democrats to nominate Horace Greeley for the presidency on a platform of civil service reform and home rule in the South. Grant won reelection, but as more scandals came to light during his second term and his Southern policy proved increasingly unpopular, his reputation plunged. The economic panic of 1873 ushered in a major depression; in 1874 the Democrats won control of the House of Representatives for the first time in 16 years.

Yet Grant's two terms were not devoid of positive achievements. In foreign policy the steady hand of Secretary of State Hamilton Fish kept the United States out of a potential war with Spain. The greenback dollar moved toward stabilization, and the war debt was funded on a sound basis. Still, on balance, Grant's presidency was an unhappy aftermath to his military success. Nevertheless, in 1877 he was still a hero, and on a trip abroad after his presidency he was feted in European capitals.

In 1880 Grant again allowed himself to be a candidate for the Republican presidential nomination but fell barely short of success in the convention. Retiring to private life, he made ill-advised investments that led to bankruptcy in 1884. While slowly dying of cancer of the throat, he set to work on his military memoirs to provide an income for his wife and relatives after his death. Through months of terrible pain his courage and determination sustained him as he wrote in longhand the story of his army career. The reticent, uncommunicative general revealed a genius for this kind of writing, and his two-volume Personal Memoirs is one of the great classics of military literature. The memoirs earned $450,000 for his heirs, but the hero of Appomattox died on July 23, 1885, at Mount McGregor before he knew of his literary triumph.