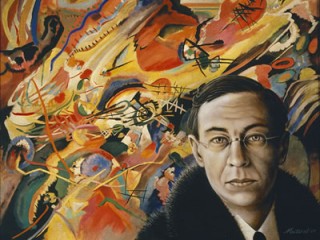

Wassily Kandinsky biography

Date of birth : 1866-12-04

Date of death : 1944-12-13

Birthplace : Moscow, Russia

Nationality : Russian-French

Category : Arts and Entertainment

Last modified : 2010-07-23

Credited as : Artist, educator, and college professor

15 votes so far

Russian-born Wassily Kandinsky was one of the great masters of modern art and an outstanding representative of the pure abstract painting that dominated the first half of the twentieth century. Though he came late to art--at age thirty--Kandinsky became highly respected for his work, theories, and teaching. During his career, he was part of several influential German artists' groups, such as the Phalanx, the Munich-based Neue Kunstler Vereinigung, the Blaue Reiter, or Blue Rider, and the Bauhaus school. During his years with the Blue Rider and at the Bauhaus, Kandinsky experimented with the psychological and emotional properties of color, line, and shape. In the process he eliminated the representational altogether, setting the course of art on a new track: that of abstraction. Kandinsky felt that painting possesses the same power as music and that sign, line, and color ought to correspond to the vibrations of the human soul. So vastly influential is his work that virtually every stylistic development since World War II bears its imprint.

Born in Moscow on December 4, 1866, Kandinsky, the son of a successful Moscow merchant, was raised in a prosperous Russian family. He studied art and piano as a child, developing a great love for music, especially opera. His parents divorced when he was about five years old, and his father took the children to live in Odessa, a city on the Black Sea. They spent the summers in Moscow when Kandinsky was a teenager; at age eighteen he moved there to attend Moscow University. The city served as a source of inspiration for much of Kandinsky's art from this period. He loved its architecture and often wrote about and attempted to capture on canvas the beauty of Moscow at dusk. He also harbored a deep fondness for church icons, religious paintings and statues, and Russian folk art.

Begins University Studies in Law

At the university Kandinsky studied law and political economics. His interest in art overtook his other concerns, however. In 1889, Kandinsky participated in a scientific mission to study the laws and customs of Syrynian tribes in the Vologda district in northeastern Russia. He was deeply moved by the region's folk art. "People in their local costumes moved about like pictures come to life; their houses were decorated with colorful carvings, and inside on the walls were hung popular prints and icons; furniture and other household objects were painted with large ornamental designs that almost dissolved them into color," wrote biographer Will Grohmann. "Kandinsky had the impression of moving about inside of pictures, of living inside pictures--an experience of which he later became quite conscious when he invited the beholder to 'take a walk' in his pictures, and tried to 'compel him to forget himself, to dissolve himself in the picture.'"

In 1896, thirty-year-old Kandinsky and his wife--he had married Ania Chimiakin, a second cousin, in 1892--moved to Munich. He studied at Slovenian artist Anton Azbe's School of Painting in Munich and later under symbolist Franz von Stuck at the city's Academy of Fine Arts. He befriended Franz Marc, with whom he and other students formed Phalanx, a group devoted to modern art and the first of several artist organizations Kandinsky would establish. His work during these early years was strongly influenced by an art nouveau-influenced style popular in Munich called Jugendstil, or Youth Style, a mixture of medieval art, curving vegetation forms like flowers and vines, and flat areas of vivid color. He was also attracted to ideas borrowed from French impressionism. In 1895 Kandinsky had seen one of the haystack paintings of Claude Monet and became fascinated by its shimmering light; he realized that the "subject"of this painting, the haystack, was less important than the effect produced by the confluence of light and color. This dramatic realization instigated the process that led him toward pure abstraction: paintings that did not "represent" a concrete subject outside of the frame.

In the early 1900s Kandinsky traveled extensively throughout Europe and North Africa with his friend and former student Gabriele Munter; he also lived in Paris for almost a year. There he became familiar with the free use of brilliant color among the Fauvists, chief among them Henri Matisse. On returning to Germany he began experimenting with these artists' advances in color and form in some of his landscape paintings. Street in Murnau and Study for Landscape with Tower employ startling hues to define space and form. The landscapes serve as a link between Kandinsky's earlier traditional work and his fully abstract style. He painted some of these scenes repeatedly, each time increasing the dominance of form and color at the expense of "subject."

From 1908 to 1909 Kandinsky founded another group in Munich, the New Artists Association. Within a couple of years, however, he and several others felt the group had become too conservative, so they splintered off to form the most famous association of all, the Blaue Reiter, in 1911. The new organization held two exhibits in 1912 and also published a yearbook of art to spread information about new developments on all fronts. Kandinsky and his colleagues believed in the concept of "total" art, arguing the legitimacy of all styles. Their yearbook contained works by and writings about various contemporary artists, as well as coverage of folk art, African art, and even children's art. They planned to publish an issue every year but were thwarted in this endeavor by the outbreak of World War I.

Develops Greater Reliance on Color

The Blaue Reiter years, from about 1910 to the beginning of World War I in 1914, were very productive for Kandinsky, both in painting and writing. While living with Munter and collaborating closely with Marc, he clarified many of his ideas. His painting, meanwhile, became more dependent on color and less on specific objects or scenes. He painted what is considered the first abstract painting in 1910. Abstract art differs from traditional styles in that instead of attempting to represent the visible world, artists working in it depend on color and form to express their inner landscape. This mode is sometimes called non-objective, as it departs from the aim of objectively representing the material realm.

Kandinsky's 1910 work, Composition I, or Improvisation, is comprised of free-form shapes of red, blue, and green joined by freely painted lines; its slashes of color lend it energy and movement. Many of the artist's works from these years have titles like Composition, Improvisation, or just color names, which further indicated his commitment to abstraction. Indeed, his use of the term improvisation, which frequently appears in the musician's lexicon, was no coincidence; a musician himself, Kandinsky saw many common elements between visual and sonic art, likening a painted line to a musical melody and complex paintings to symphonies or jazz improvisations. And he understood implicitly that composers generally do not bother with the question "What is this concerto supposed to represent?"

The most important influence upon Kandinsky's artistic beliefs was the German mystic Rudolf Steiner, founder of a variant of Theosophy, which itself had been founded in 1875 by Helena Petrovna Blavatsky and Henry Steel Olcott in America. This new religious movement as a whole suggested a hidden meaning within all material culture. Blavatsky's Anglo-American sector stressed the unity of the world's religions, whereas Steiner believed in the centrality of Christ. As early as 1909 Kandinsky was editing some of the writings of Steiner. All theosophists adhered to the notions that the spiritual world was in reach of the average person and that artists were charged with aiding people to contact the "vibrations" of that other world. The materialistic culture was certain to give way soon to a higher, spiritual stage of human development.

Publishes Ideas on Art

Concerning the Spiritual in Art sets forth Kandinsky's rationale for abandoning representational painting. In this work he describes his commitment to the values of theosophy and his rejection of materialistic principles. He also provides a unique conception of the use of colors and a new method of space and form in art. Kandinsky completed this work in December 1911, and it was published the following year at about the same time that his artistic work began reflecting his new abstraction. Making analogies to the writing of Maurice Maeterlinck, the music of Claude Debussy, the dance of Isadora Duncan, the colors of Henri Matisse, and the forms of Pablo Picasso, Kandinsky explains his notion of abstract value by looking for hidden meaning in art, meaning not found simply in the external expression. Viewers of art, he argues, should allow the work to speak for itself in order to understand its abstract effect.

In Concerning the Spiritual in Art Kandinsky refers to the spiritual triangle. At the bottom of this figure stand the broad masses, for whom realistic representation is a comfort, albeit a comfort without a soul. Barely above this broad stratum are those artists who appear to be avant garde because they adopt some peculiar style without real meaning; they pretend to have captured some hidden significance but in reality only court the devotees of the newly fashionable. Higher on the triangle, and therefore lesser in number, are those who recognize uncertainties, who question the assertions of positivism and science but are at a loss to provide new answers. Those at the top of the triangle, the least numerous and least popular, are the spiritual leaders who recognize that an era of spiritual darkness has descended. It is this group, often artists, who provide a glimmer of light from which the new age can ripen. Kandinsky saw the prophetic role of the artist, whether literary, visual, or musical, as helping to save civilization from material degradation. He perceived merit in the thoughts of Blavatsky, Steiner, and other theosophists, as well as in others who examined "nonmatter."

This spiritual dimension of art extends to Kandinsky's detailed discussion of color and form. Certain colors are apt to cause a defined impression in limited use, but then grow stale. The task of the artist is to render colorful impressions with deep and lasting meaning. Soft blue was a color accented by the symbolist movement. Kandinsky developed the same argument with respect to forms. All forms say something, even if it is not immediately understood by the artist. In any case, the union of color and form must never be merely decorative, an empty response to the need for nonrepresentational art. The future of art lay precisely in the harmony between form and color, divorced from material objects.

By 1914 Kandinsky had developed two styles of painting: the compositions, in which he planned the arrangement of geometric shapes, and the improvisations, in which he let his subconscious self paint as it wished. The same year that Kandinsky published his Concerning the Spiritual in Art, Klange appeared. This collection of improvisations and prose poems, written in German and Russian, was translated into English in 1981 as Sounds. "In either language the poems read as though they were written in a kind of basic English (or German), like instructions on the box of a do-it-yourself kit," observed Stephen Spender in the New York Review of Books. "They often have humor, but underneath there is the tone of another kind of instruction, on how to live in an apocalyptic era." "It is true that since Kandinsky's language lacks a rich verbal texture of the kind one expects in poetry, one has to look for other qualities to explain its very real appeal," continued Spender. "It combines sharpness, brightness, precision with an underlying ominousness, and this is due to the positioning of words so that they make one see beyond them into colors and sounds they represent. It is excellent painter's poetry or wordpainting."

Joins Bauhaus

When World War I broke out, Kandinsky left Germany for Switzerland. He then returned to Russia, where after the Russian Revolution he took an active role in reorganizing many art schools and museums; he painted very little during these years. By 1921 his art had begun to fall into disfavor with his country's new Communist government. He returned to Germany and was invited by architect and designer Walter Gropius to become a teacher at the Bauhaus, an innovative new art school. Kandinsky was a member of the faculty there for about five years, teaching mostly painting theory. During this time he also published his second book on art, Point and Line to Plane.

Kandinsky sought a "language"of color and form that would express feeling in much the same way musical notes do. His interest in music inspired him to write two plays with musical accompaniment, Black and White and The Green Sound. He also worked on a one-act opera, The Yellow Sound, in which he attempted to create a total art environment, employing visual art, music, dance, and theater. The Yellow Sound was not produced, however, until 1982, when it served as the centerpiece of an exhibit of Kandinsky's paintings at the Guggenheim Museum in New York.

Kandinsky's art from the 1920s makes greater use of geometric forms than had his previous work. He may have been influenced during his stay in Russia by artists working in a style known as Suprematism, as well as by Bauhaus ideas. Yellow, Red, Blue and Dividing Line, two paintings from these years, feature lines that appear to have been drawn with a straight edge rather than freehand. Nonetheless, they amply convey the energy and movement of his previous work.

A Dangerous Spirit

When the Nazis came to power in Germany in the early 1930s, they closed numerous art schools, including the Bauhaus. Kandinsky in particular was singled out; the director of the Bauhaus was ordered to fire him, Nazi officials insisting that the Russian artist "is dangerous for us due to his spirit." The Nazis confiscated fifty-seven of his works, labeling them "degenerate art." In response, Kandinsky moved to Paris and took up residence in an apartment located for him by artist Marcel Duchamp. He lived there for the rest of his life and became a French citizen in 1939, five years before his death on December 13, 1944, in Neuilly-sur-Seine, France. Influences of the new surrealist style developing in Paris in the 1930s can be detected in Kandinsky's later works. Despite their persistent abstraction, some, like Mouvement, from 1935, utilize the wavy lines, amoeba-like forms, and intense colors favored by the surrealists. Kandinsky himself remarked, "The creation of a work of art is like the creation of a world."

Speaking of these later works, an essayist for the International Dictionary of Art and Artists reported: "Though there are many fine works, one senses overall a waning of the vitality of Kandinsky's early development, though his belief in the messianic power of art never wavered. He continued to have faith in the artist's power to equal the immense task of elevating the world to the realm of the divine. In the midst of economic and political turmoil, he saw himself as the leader of a spiritual revolution."

Posthumous Exhibit Influences Art World

One of the major collectors of Kandinsky's art during his lifetime was wealthy American Solomon Guggenheim, founder of the Museum of Non-objective Art in New York--later the Guggenheim Museum--the collection of which was at first mostly comprised of Kandinsky's works. Through various exhibitions and key art dealers who brought his works to the United States, Kandinsky's ideas began to influence U.S. painters. An exhibition in the spring of 1945 in New York, a few months after Kandinsky's death, had a tremendous impact on the art world, as did many others well into the contemporary era. In the 1940s such artists as Arshile Gorky and Stuart Davis found great power in his works. So too did artists Jackson Pollock, Hans Hoffman, Lee Krasner, and Willem de Kooning, who established the new movement called abstract expressionism. These artists further explored Kandinsky's conviction that art comes from within and need not refer explicitly to the physical world. Along with Pablo Picasso and Matisse, Kandinsky is considered one of the most influential artists of the twentieth century. As a writer for Time International stated, "At the dawn of the 20th century Russian-born artist Wassily Kandinsky discovered the aesthetic and emotional power of non-representational art through imaginative forms of vivid, glowing colors. Working on the threshold of abstract art, Kandinsky ... became its leader and trailblazer, inspiring scores of painters to follow in his footsteps."

PERSONAL INFORMATION

Born December 4, 1866, in Moscow, Russia; naturalized German citizen, 1928; naturalized French citizen, 1939; died December 13, 1944, in Neuilly-sur-Seine, France; married Anja Chimiakin, 1892 (divorced); partner of Gabriele Munter (a painter), 1902-13; married Nina Andreevskaya, 1917.

CAREER

Associated with various arts groups, including Phalanx group, Munich, Germany, 1902-04, Neue Kunstler Vereinigung, Munich, 1909, Der Blaue Reiter group, Munich, 1911; Free State Art Studios, Moscow, Russia, professor, 1918; founded Russian Academy of Artistic Sciences, 1921; Bauhaus, Weimar, and Dessau, Germany, deputy director and professor, 1922-33. Exhibitions: Works included in museum collections throughout the world, including the Kandinsky Collection, Neuilly-sur-Seine, France; Städtische Galerie, Munich, Germany; Guggenheim Museum, New York, NY; Russian Museum, Leningrad, Russia; and Chicago Art Institute, Chicago, IL.

WORKS

* WRITINGS

* Stikhi bez slov, [Moscow, Russia], 1904.

* Xylographies, [Paris, France], 1909.

* Über der Geistige in der Kunst, [Munich, Germany], 1912, translation published as The Art of Spiritual Harmony, [London, England], 1914, translated by Michael Sadleir as Concerning the Spiritual in Art, Dover (New York, NY), 1977.

* Klange (prose poems), Piper (Munich, Germany), 1912, translation by Elizabeth R. Napier published as Sounds, Yale University Press (New Haven, CT), 1981.

* (Editor with Franz Marc) Der blaue Reiter, [Munich, Germany], 1912, new edition, edited by Klaus Lankheit, [Munich, Germany], 1965, translation published as The Blaue Reiter Almanac, Da Capo (New York, NY), 1974.

* Tekst Khudozhnika, [Moscow, Russia], 1918.

* Punkt und Linie zur Flache: Beitrag zur Analyse der malerischen Elemente, [Munich, Germany], 1926, translation by Howard Dearstyne and Hilla Rebay published as Point and Line to Plane, Dover (New York, NY), 1947, reprinted, 1979.

* Essays über Kunst und Kunstler, edited by Max Bill, [Stuttgart, Germany], 1955.

* Briefe, Bilder und Dokumente eine aussergewohnlichen Begegnung, edited by Jelena Hahl-Koch, [Salzburg, Austria], 1980, translation by John C. Crawford published as Arnold Schoenberg, Wassily Kandinsky: Letters, Pictures, and Documents, Faber (London, England), 1984.

* Complete Writings on Art, two volumes, edited by Kenneth C. Lindsay and Peter Vergo, G. K. Hall (Boston, MA), 1982.

* Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, Briefwechsel: Mit Briefen von und an Gabriele Munter und Maria Marc (letters), edited by Klaus Lankheit, Piper (Munich, Germany), 1983.

* Wassily Kandinsky and Gabriele Munter: Letters and Reminiscences, 1902-14, translated by Ian Robson, Prestel (Munich, Germany), 1994.

* Also author of plays Black and White and The Green Sound, and of the opera The Yellow Sound, produced at Guggenheim Museum, New York, NY, 1982.